The gospel according to Harry

Umpire, broadcaster, raconteur, innovator and showman, Henry ‘Harry’ Beitzel was born in working class Fitzroy in 1927. He grew up steeped in football history: his dad Arnold had played 19 games for St Kilda and Fitzroy after returning from World War I, and his cousin Barry later played a few games with Carlton. The young Harry idolised Fitzroy’s Brownlow Medalists Haydn Bunton and Wilfred ‘Chicken’ Smallhorn and dreamed of one day emulating their feats. Harry’s father had played a key role in recruiting Chicken to Fitzroy and the Smallhorn family lived in the same street.

At school Harry was a good athlete and represented Victoria in schoolboy football. He was also a handy cricketer and once shared an unbeaten 104 run partnership with class mate Neil Harvey against Moonee Ponds, although Beitzel points out that he scored just six of those runs. He also played cricket and football for the East Brunswick Methodists in the local church competition. He describes his attitude to religion as an “inherited faith” which was underpinned by the practical requirement that he had to attend Sunday School at least twice a month to be eligible to play for the church team.

After playing several games with Fitzroy Seconds late in World War II, Beitzel fell into umpiring by accident after his boss - who also happened to be in charge of recruiting umpires for the VFL - suggested he give it a try. For a while he juggled both umpiring and playing, until his coach at Fitzroy advised him to “stick with the umpiring.”

He progressed quickly through the umpiring ranks and umpired his first VFL game late in the 1948 season, aged just 21. It was Collingwood vs St Kilda at Victoria Park. Collingwood won easily but the home fans - angered by one of Beitzel’s decisions late in the game - had their own way of showing their displeasure. In those days, the umpire shared the players’ race with the home side. When the Collingwood players waited for Beitzel to leave the ground first he thought they were just being polite, but it turned out the home fans were waiting to “christen” him as he went up the race. In the rooms afterwards, Collingwood’s president and former star player Syd Coventry apologised for the fans’ behaviour. Beitzel still remembers his reply: “Thank you Mr Coventry, but don’t worry. Just imagine if you’d lost - I woudn’t have gotten off the ground!”

From his very first game, Beitzel made it a habit to visit the players in the rooms afterwards. He didn’t drink, but would get to know the players over a lemonade, explain the decisions he’d made during the game and candidly admit when he’d gotten one wrong.

Between 1948 and 1960 Beitzel umpired 182 VFL games, capped by the 1955 Grand Final between Melbourne and Collingwood. He also umpired at the 1956 interstate carnival, at many country games and a number of matches in Tasmania. On the field he was known for his decisive actions and his clear directions to players. He also sought to let the game flow unimpeded by the whistle as much as possible: after one semi final in 1951, the Mercury’s correspondent noted that Beitzel “gave the man in possession every chance to get rid of the ball, and by ignoring worthless technical breaches ensured that the game flowed freely.”

Beitzel maintains that clear and unambiguous umpiring is important because how players respond to a decision can influence a crowd and affect the whole match atmosphere:

The stagers and the personality players could make you or break you, just through their body language. Earning the coach’s respect was also very important: for them there’s nothing worse that a ‘home ground’ umpire.

Asked to name the best player he ever umpired, Beitzel unhesitatingly nominates the great John Coleman. He umpired Coleman’s first VFL game in round 1 1949, when he kicked 12 goals on debut.

When an ongoing Achilles tendon injury ended his umpiring career in 1961, Beitzel turned to radio and TV broadcasting, becoming one of the sport’s best known commentators during stints at 3KZ, 3AW, 3AK, the ABC and Channels 2 and 9.

On air, Beitzel sought to involve and inform the listener. He successfully gambled on a 12 noon to 6 pm footy broadcast, opening with his signature line “Harry Has His Say!”, followed by live pre-match personality interviews, the game itself, then open line talk-back with the fans. He was innovative in his use of match previews, expert commentary, statistics and live interviews to inject colour and drama into his broadcasts. He also introduced “around the grounds” commentators, who provided updated scores and half time and post match summaries. It was six hours of non-stop football.

In his book The Stats Revolution, former Carlton champion Ted Hopkins credits Beitzel with changing the way football was heard, read about and discussed:

Beitzel was football’s first multi-media superstar. He was as prominent as Eddie McGuire is today, but had more influence on how football is played and talked about.

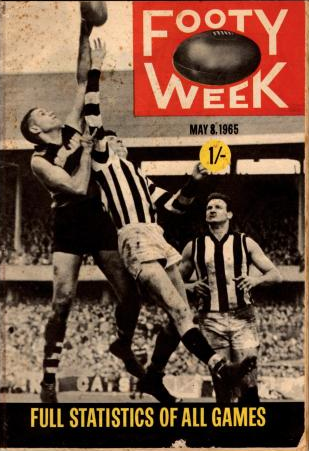

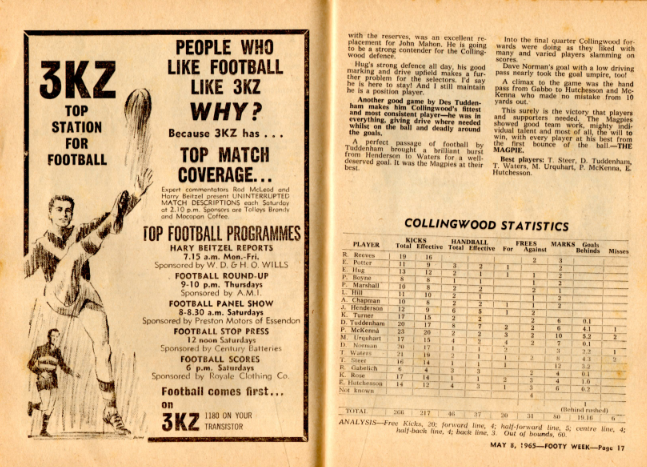

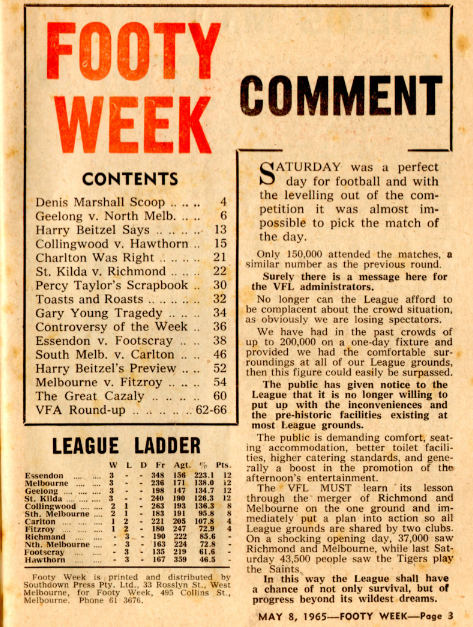

After writing for several newspapers Beitzel founded Footy Week magazine in 1965. This was another innovation in which he took advantage of the newly developed offset printing process to write, compile and print Footy Week every Sunday in time for its distribution the next morning. Beitzel knew he had to offer the football public something different to what the Melbourne papers were providing. His answer was twofold: better photography and more match statistics based on every player’s performance.

After writing for several newspapers Beitzel founded Footy Week magazine in 1965. This was another innovation in which he took advantage of the newly developed offset printing process to write, compile and print Footy Week every Sunday in time for its distribution the next morning. Beitzel knew he had to offer the football public something different to what the Melbourne papers were providing. His answer was twofold: better photography and more match statistics based on every player’s performance.

The photographic innovation came courtesy of Mal Thomson, a self taught photographer whose home made lenses and camera motors enabled him to capture that split second image that the newspaper photographers often missed.

In terms of stats, “Footy Week became the bible, with kicks, marks, handballs, frees and score details,” according to Hopkins. Former VFA and VFL player Tommy Lahiff became a regular columnist and Beitzel would use his editorials to campaign for improvements to the running of the game and better facilities for the fans. Beitzel was breaking new ground in print reporting, just as he had done in broadcasting.

Like umpiring, Beitzel fell into public speaking almost by accident, after he was asked to speak to a men’s club that met at his church prior to the Sunday evening service. Word spread, and before long he was speaking to Christian groups across Melbourne. One day he accepted what he thought was another such engagement, only to find out just days before the event that he was expected to address a large congregation from the pulpit of Essendon’s Church of Christ. Worried about what he should say, he sought the advice of his friend, former Fitzroy star player and Aboriginal pastor Doug Nicholls. The result was an address entitled ‘Who’d be an Umpire?’, in which Beitzel compared the laws of football with the ten commandments.

For the next decade, he spoke wherever he was asked: school assemblies and speech nights, service clubs, football fundraisers, even the Catholic training seminary. He never charged a fee as he felt it was an honour to be asked to spread the football message.

Beitzel’s speaking engagements led him to make an early discovery:

Public speaking is based on two requirements: being able to inform and to entertain. Of these, being able to entertain is perhaps the most important.

Beitzel believed the best way of inspiring an audience was to give them examples of successful people and then encourage them to develop their own formula for success. For inspiration, he drew on the messages and techniques of American motivational speakers, adapting them to an Australian environment. Napoleon Hill - best known for his saying “A quitter never wins and a winner never quits” - made a particular impression on him.

He found young children to be the toughest audience to engage, followed by senior high school students, “because of course they know everything and their parents and teachers know nothing.” Whichever theme he chose for his talks, he always related the message back to football in some way.

In 1967, Richmond’s coach Tom Hafey invited Beitzel to address his players before the Grand Final against hot favourites Geelong. He chose as his theme ‘Up on Cloud Nine’, asking the players to first visualise themselves on the winners’ dais, and then to focus on what was required to get them there. It was Kevin Sheedy’s first year at Richmond; he has said that Beitzel’s talk helped change his life and describes him as one of the best speakers he heard during his time at the club. Sheedy and Beitzel would later team up to release their own motivational book, Second Chance Winners.

Always keen to expand the game’s profile, in 1967 Beitzel organised a team of players from the six VFL clubs who sanctioned his enterprise to play several matches in Ireland. The tour was underwritten at Beitzel’s own expense (he mortgaged his home) and proceeded despite only lukewarm support from the VFL and Irish authorities and criticism by the Victorian RSL that the touring uniform included a digger’s slouch hat.

Led by Carlton’s captain coach Ron Barassi and embracing the nickname ‘the Galahs’, the Australian team played their opponents under full Gaelic football rules. They beat all comers in Ireland and played an exhibition match of Australian Rules in London against a team of ex-pats. On the way home they lost a spiteful game of Gaelic Rules in New York in which Barassi had his nose broken and ‘Hassa’ Mann fractured his ribs.

Led by Carlton’s captain coach Ron Barassi and embracing the nickname ‘the Galahs’, the Australian team played their opponents under full Gaelic football rules. They beat all comers in Ireland and played an exhibition match of Australian Rules in London against a team of ex-pats. On the way home they lost a spiteful game of Gaelic Rules in New York in which Barassi had his nose broken and ‘Hassa’ Mann fractured his ribs.

The following year Beitzel took another Australian side abroad to play a further series of matches in Ireland, London and New York. This time he drew on a wider pool of players from the VFL, VFA, Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia and Sydney and staged further exhibition games of Australian Rules. By the end of the 1968 tour The Galahs were the Gaelic World Champions.

This inspired Beitzel to suggest a World Series Gaelic Cup involving Ireland, USA, NZ and Australia, with each country to deposit $10,000 in Ireland. Beitzel’s money was the only cash deposited and it sat in the Bank of Ireland earning interest until 1978, when he resurrected the Galahs concept with the support of the VFL’s Allen Aylett and Jack Hamilton. The end result was the International Rules Series (IRS) between Ireland and Australia, which was officially launched in October 1984.

The international tours had two important outcomes: they allowed Australian footballers to represent their country for the first time and they showcased the code to Irish footballers, effectively opening the door for the Irish experiment that was to follow during the 1980s.

Beitzel’s television commitments during the 1960s to the late 1980s included hosting ABC’s Focus on Football on Friday nights and Football Review on Saturdays. His fellow panelists were all former footballers and included ‘Chicken’ Smallhorn, Jack Dyer, Roy Wright, Bert Deacon and Laurie Nash. It was a simple format: Beitzel would ask each panelist to offer a prediction or give their first hand report from the match they had seen that day. Beitzel concedes that his years of public speaking must have helped prepare him for the chairman’s role, but says now:

I don’t think it was any special gift, it's pure instinct. I likened my role as chairman of the panel to a slips fielder who pulls off the ‘miracle’ catch after diving and somersaulting but still takes the catch. A chairman needs instinct with a quick quip or comment to keep the discussion moving.

Beitzel also continued to broadcast football games on radio. At 3KZ he teamed up again with Tommy Lahiff to form a much–loved combination. “Are you there, Tommy?” Beitzel would ask, to which Lahiff would invariably reply from the dressing room: “Can you hear me, Harry?” First at 3KZ, then at 3AW, 3AK and finally 3WRB, their on air partnership lasted more than three decades.

Beitzel also continued to broadcast football games on radio. At 3KZ he teamed up again with Tommy Lahiff to form a much–loved combination. “Are you there, Tommy?” Beitzel would ask, to which Lahiff would invariably reply from the dressing room: “Can you hear me, Harry?” First at 3KZ, then at 3AW, 3AK and finally 3WRB, their on air partnership lasted more than three decades.

Beitzel resumed his involvement in umpiring in 1980-1 when he was asked by the VFL to become its first director of umpiring. He accepted the position on the proviso he could continue his media career. He also sought an increase in the salary from $10,000 to $40,000 per year; when Jack Hamilton accepted the terms Beitzel donated the money back to be spent on improving umpires’ conditions. Knowing that the result of a game can hinge on one bad call, he used his position to argue that umpires needed to become more accountable for their decisions. He also felt umpires had become too ‘whistle happy’ and under him the average number of free kicks given per game fell dramatically.

Media and business commitments continued to occupy Beitzel throughout the 1980s. He was never far from the action and when the privately owned Sydney Swans were put up for sale in 1988 he even helped organise an abortive bid by a New Zealand marketing firm to buy the club.

Beitzel’s public reputation and private confidence took a severe hit in 1989 when he was accused of obtaining financial advantage by deception while working as a promoter for Soccer Pools. Despite glowing character references from many of his friends, he was convicted in late 1994 and served eight months at a minimum security prison farm. To this day, Beitzel maintains that any deception on his part was unintentional and that he only pleaded guilty because, in the absence of a former business associate, an accountant (who had fled overseas), he had no defence to offer.

Having served his penance, Beitzel began his journey back to community acceptance, even subjecting himself to some friendly jibes on Channel Nine’s Footy Show. His media commitments slowed, but he retained his passion for the game and its future. In 2006, his public rehabilitation continued when he was inducted into the Australian Football Hall of Fame for his contributions to the game.

These days, Beitzel preaches the gospel of football via social media. Having embraced email he has given himself a roving commission to call football as he sees it, whether it’s the “over analysis” of controversial on-field incidents by the media or inconsistent findings by the Match Review Panel.

His thrice weekly emails - headed “HB Has His Say!” - reach the inbox of some of the game’s most influential commentators, coaches and administrators, who are treated to Beitzel’s own take on footy events, both on and off field. Nothing seems to escape his attention, or his judgment. He admires Buddy Franklin’s athleticism, for example, but is dismayed by his showiness and feels he is given too much leeway by umpires when he steps off the mark during his run up approach to goal. He is also critical of umpires who are reluctant to pick free kicks out of “mauling packs” and instead take the easy option of balling it up. He says its understandable that players hold the ball in because they know they will “be rewarded by an impotent [umpiring] decision which plays into the coaches’ defensive ‘stoppages’ game plan.”

In fact, Beitzel reserves some of his harshest criticism for today’s umpires. His own background has convinced him that umpires need to have played the game in order “to understand the flow, consistency and commonsense of the role.” Such understanding allows umpires to maintain control of the game. As he recalls, “when I was director of umpiring I made it clear to the umpires if I had to report a player then I was mostly to blame [because] I had lost the respect and control of those players.”

Beitzel is an unabashed fan of Andrew Demetriou, who he says has taken the AFL into an unrivalled era of growth and professionalism, but believes there is always room for improvement in the game’s administration. He has been around long enough to recognise spin when he hears it, yet he remains optimistic enough to think that there’s not much wrong with football that can’t be fixed with logic and common sense.

Although a member of the Sydney Swans and the Greater Western Sydney Giants, he can appreciate good football regardless of who is playing. “As a spectator I enjoy my footy differently to the 'one-eyed' club fanatic,” he says. “I don't barrack, curse or abuse. I admire in silence.” Through it all, he retains an intuitive grasp of what ordinary fans are thinking about the game. There aren’t many commentators like him, and certainly none with his unique blend of experience and insight.

Having reached an age when others might be slowing down, Beitzel plans to keep on calling footy as he sees it. He will still go to watch games, whether it’s the Swans, the Giants or his local junior side. He will keep encouraging the AFL to push further into the barbarian strongholds of rugby league. And he will keep telling those in authority when they get things wrong. Harry Beitzel’s missionary zeal for Australian Football will sustain him for some time yet.

Comments

Harry Beitzel's contribution to the game has been significant and its great to see this recognized, particularly his induction into the Hall of Fame, but also through articles such as this that record his achievements. We plan to add to that legacy by reproducing here at australianfootball.com articles, stats, and other material from Harry's 'Footy Week' magazine, a pioneer publication in terms of footy analysis and stats presentation. Stay tuned.

Gerry Daley 23 October 2014

Love to see some Footy Week on this site. Great source of history. Harry is obviously a "one of a kind" bloke and an ongoing asset to the great game.

Login to leave a comment.