SOFI report: Conflict and climate change reduce access to food and increase hunger

There are 734 million people going hungry around the world, 122 million more than in 2019, according to newly released UN figures for 2022.

Launched last week by agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Food Programme (WFP), ‘The State of Food and Nutrition in the World 2023’ (SOFI) report estimates 29.6 percent of the world’s population, around 2.4 billion people, had restricted access to food last year.

This includes around 900 million people facing severe food insecurity amid worsening and intersecting crises.

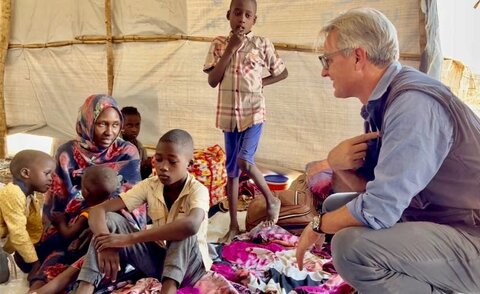

“The populations we serve are constantly being put under increased pressure,” said Michael Dunford, WFP’s Regional Director for East Africa. “(Conflict in) Sudan is coming at the worst possible time and, unfortunately, it has potentially regional implications. We’re already seeing considerable movements of populations out into Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Egypt.”

“Up until recently, we would describe the region as being on fire,” he added. “Now it feels as though the region has been doused with petrol. At every turn there seems to be yet another emergency, either through conflict or through climate.”

Most of the 500,000 people who have fled Sudan since the outbreak of conflict there in April have arrived in Egypt.

“For us it adds another crisis to a very limited funding portfolio,” said Corinne Fleischer, WFP Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa and Eastern Europe, covering protracted crises including Yemen, Syria and now Ukraine.

‘Unseen and unheard’: Haiti weathers hunger, gangs and climate extremes

“It also puts a big additional burden on Egypt which is already providing social services to Syrian and Palestinian refugees,” she added.

“The region is doing worse than others, with import-dependent countries heavily impacted by the war in Ukraine – food inflation is at 30 percent, placing the prices of basic foods out of reach for millions.”

The poorest countries which don’t export oil suffer the worst. So in huge, long-running crises such as Yemen and Syria, “WFP is cutting the number of people we serve by some 8 million”.

“Funding doesn’t allow us to continue with the almost 20 million people we support in both countries every month,” Fleischer said. “It’s tragic and at such a scale it shakes the system.”

The SOFI report charts a worrying ‘megatrend’ of urbanization, accompanied by a rise in urban hunger as more and more people flock to cities in search of a better life.

More than a million people have been forced to leave their homes in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) alone since January, bringing to 5.5 million the total number of internally displaced people in the region.

With a recent influx of 800,000 people into Goma, a city of 1.2 million people, “You are actually uprooting basic social structures in every form and manner,” said Peter Musoko, WFP Country Director for DRC. The World Health Organization has warned of a total breakdown of health services, landing people in the jaws of disease and malnutrition.

A humanitarian last stand: Why conflict and hunger risk being eastern DRC’s main exports

Things are no better across the African continent and the Middle East.

Fleischer recalled the ‘immense’ reaction to WFP being forced to cut off assistance to 2.5 million people in Syria. “Having to cut assistance to 40 percent of those who really rely on it is really a shock to the system that can have repercussions far beyond the country, far beyond just hunger,” she said.

“Palestine is an ignored crisis,” she added. “We’re very concerned. We’ve cut 60 percent of our beneficiaries and yet we have no funding outlook to be able to continue with the 150,000 people we still serve. And what’s really concerning and should concern everybody is that UNWRA (the UN relief and works agency for Palestine refugees) is in the same situation.

“WFP and UNWRA together account for 30 percent of the GDP in Gaza. UNRWA will not pay salaries unless they get substantial funding, will not do their own food assistance to refugees unless they get more money. Also, the Palestinian Authority’s social safety net is currently in a big fiscal crisis and they’re also not providing. So what will happen in Palestine if nobody receives assistance?

“That is a recipe for disaster in an already very volatile and ever-escalating political context.”

To make matters worse, “the MENA region also doesn’t have the water to produce food locally,” Fleischer said.

Water is an issue Michael Dunford is acutely aware of, having witnessed the devastating impact of the Horn of Africa drought. “Over the course of five failed rainy seasons, 23 million people have been impacted, more than 2 million displaced, over 10 million livestock dead,” he said.

“Without water security, we can’t have food security. And all this in a theatre where there is already ongoing conflict, such as in Somalia.

“This multiplier of shocks is truly weakening the capacity of the populations to meet their own needs. And that is why WFP, with others, needs to be continually investing in resilience programmes so that we create a safety net, we create absorption capacity for people to take the shock and not have to rely on others."

Developing capacities “is one of the things we’re excited about,” said Dunford.

“WFP has invested in working with smallholder farmers, working to build up anticipatory action activities, working at a whole range of levels – particularly regional and local government – building capacity,” he added.

“We have to make sure resilience has a fighting chance, make sure that we are able to build a strong enough case that shows that resilience works.”

Fostering and maintaining trust is also critical to emergency response, as Ethiopia testifies.

“Ethiopia is tough, we’ve been forced to pause our humanitarian operations because of widespread - or what are perceived to be widespread - diversions there.

“We feel as though all systems need to be revisited, strengthened, so that we can be confident that the food that we are delivering is actually ending up in the hands of the people who need it most," said Dunford.

“But that is going to create increased pressure on ourselves, the Government and our donors, to put that assurance project in place as quickly as possible, so that humanitarian response can be recommenced.”

WFP needs US$25.1 billion to reach 171.5 million people around the world this year.