Uncharacteristically for a composer who will talk genially about all sorts of subjects except herself, Judith Weir is taking stock of her life. It’s appropriate. This month she turned 70. This summer she will give up what she describes as the “rather Ruritanian title” she has held for the past ten years: Master of the King’s (formerly Queen’s) Music. The King is already in the process of picking her successor. The role has no fixed responsibilities, but it’s customary for its holder to write music for royal occasions.

And next month the Aldeburgh Festival mounts a retrospective of her music. It ranges from the mini-opera she wrote for solo voice 45 years ago, King Harald’s Saga (“Jane Manning sang it everywhere and gave me a career”), to two new pieces: a string quartet and an orchestral work, Planet, inspired by photographs of Earth taken from space.

I remind Weir of another anniversary. It’s just over half a century since we first met, in what was then quaintly called a “harmony and counterpoint” class when we were first-year music students at Cambridge. She laughs. “It was a completely different world, wasn’t it?” she says. “The computer played absolutely no part in our lives as musicians. The internet hadn’t been invented. If you wanted to get a souvenir of a piece you had written you had to lug in a big reel-to-reel tape recorder. Speaking as a composer, I’m much happier about the way things are now.”

And as with athletes constantly shaving microseconds off world records, musical standards have risen too, haven’t they? “Enormously,” Weir says. “Today’s students have absolutely no trouble performing old pieces of mine that were once thought very difficult. In fact a bassoon player suggested to me that Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring should be transposed up a semitone every few years so we can feel how impossible that opening solo must have seemed to the first performers.”

Two other things have changed beyond recognition. When Weir started there was tremendous pressure for young composers to write in a certain style if they wanted serious commissions. That style was the modernist serialism pioneered by Schoenberg and Webern and intensified by Boulez and Stockhausen. Bravely, and without much support, Weir resisted from the start. Even in those student years she never went along with the modernist crowd.

Advertisement

“Yes, in those days you had to bow to serialism, no matter who you were,” she says. “Even Britten and Stravinsky did to an extent. I think people were puzzled by me. Very early on I wrote a suite based on Yugoslav folk music. People said: ‘What on earth is this thing?’ Nowadays it’s the opposite. The genres have exploded. The difficulty for young composers today is deciding which of a multitude of styles they want to write in.”

And the other big change? Successful female composers. You now count them by the dozen. When Weir started she had pioneers to emulate — Thea Musgrave, Elizabeth Maconchy, Ruth Gipps and the like — but it was vanishingly rare to encounter their music in concert halls.

“And because women composers were so rare, people felt there was something a bit odd about them,” Weir recalls. “There was almost an uneasiness around their work. For a long time if I was asked to serve on a panel I was nearly always the ‘token woman’.”

Perhaps because her music was so attractive — and because she’s always had a nose for an intriguing story, usually wrapped in a mysterious mythic aura — Weir had a lot of early success in the opera house. She says her gloriously quirky 1987 romp A Night at the Chinese Opera isn’t done much these days because of concerns about non-Asian singers portraying Asian characters (“Though if an all-Chinese cast could be organised I would be fine with that,” she adds wryly).

However, her supernatural thriller Blond Eckbert is being newly staged to open the Aldeburgh Festival, then taken on the road by English Touring Opera. It has always struck me as a very enigmatic piece. Is that how she intended it? “Yes, I think enigma is what opera can do really well,” she says. “It’s why I don’t like productions of my operas where the director has imposed a really strong view of what he or she thinks it means.”

Advertisement

Has she ever winced when sitting through a production of one of her operas? “Well, it’s like giving away your own child,” she says. “I don’t think people realise how little control the composer has once the production team get their hands on it. Seeing a new staging for the first time, you can easily have an ‘oh my God’ moment. My hope is only that the narrative gets presented clearly. Some opera directors seem to think: ‘This has been done a few times, everyone must be bored with it, so I need to be radically different.’ Whereas with something like Blond Eckbert there will probably only be two people in the theatre, including me, who’ve seen it before.”

Weir’s time as Master of the Queen’s/King’s Music has been eventful. She supplied new choral pieces for the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II and the coronation of King Charles. One senses, however, that like her predecessor, Peter Maxwell Davies, she will consider her most important work as Master to have been championing British music and musicians at a difficult time. For instance she has just helped to launch a crowdfunding scheme (musicpatron.com) to support young composers.

• Meet the royal composer who wrote music for the Queen’s funeral

“Yes, I’ve made it my mission — and unfortunately it has kept me very busy — that when I hear of cuts to music I immediately fire off a letter or meet the people concerned,” she says. “Sadly over the past few years it’s become an almost daily occupation.”

Does the King care about such things? “The King has to stay out of politics,” Weir replies. “But he’s very aware of what’s happening in musical life, and yes I think he cares very much.”

Advertisement

She has also championed music in schools, which she frequently visits. “I think it’s a very useful part of the job,” she says. “I could just write to a school and say, ‘I’m Judith Weir, I’m a composer, can I come and teach your GCSE classes?’ but I might seem a bit weird. Having this link to the monarchy opens doors more easily.”

Does it upset her when she hears music described as a “soft” subject, as it had been by a cabinet minister on the very morning that Weir and I meet? “It really won’t do,” she replies vehemently. “Music is actually a very challenging subject. It involves history, theory, performance, composition and really thinking about communication and teamwork. Why is it that when you visit a private school the first thing they show off is their big music block? If music is important in the private sector it should be just as central in state schools.”

When Weir quits being the monarch’s music master, what next? “My big ambition is to go to more concerts that are nothing to do with me,” she replies. “After 50 years in this business my enthusiasm for music is as great as ever. Don’t you feel the same way?”

Blond Eckbert opens the Aldeburgh Festival on June 7, brittenpearsarts.org

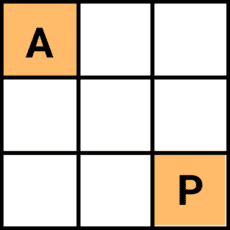

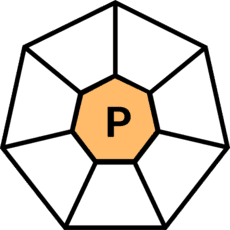

Who will be the new Master of the King’s Music?

by Neil Fisher

James MacMillan

The 64-year-old has an immense body of work behind him — including a superb anthem written for Elizabeth II’s funeral. Politically outspoken, however, the Catholic unionist Scot may ruffle too many feathers.

Advertisement

George Benjamin

Another musical knight, also 64, the softly spoken composer would be the connoisseur’s choice. Hard to see him writing royalist music to order, though.

Roxanna Panufnik

Panufnik, 56, was one of the coronation service composers, so we know she’s on an approved list. Her wide-ranging work includes two deft community operas for Garsington, which bodes well for such a public role.

Tarik O’Regan

A particularly fine choral composer, the 46-year-old grew up in Croydon. He draws on his mixed Irish and Algerian background in his music — and, like Panufnik, had success with a premiere at the coronation.

YolanDa Brown

No one said it had to be a classical specialist. The charismatic 41-year-old Londoner, a saxophonist and composer, is already a terrific advocate for music in the UK and was chair of Youth Music for six years.

Who should be the new Master of the King’s Music? Leave your suggestions in the comments below