The Sweet Life

On the eve of his 100th birthday, Wayne Thiebaud—the Sacramento painter best known for his evocative portrayals of desserts that look good enough to eat—talks about the new pieces he’s working on (yes, he’s still wielding a brush—and a tennis racket!), his favorite kind of pie, and why, despite his status as one of America’s most important living artists, he still sees himself as “just an old art teacher.”

Wayne Thiebaud prefers to paint from memory. That’s because no mere photographic image, however detailed or expertly framed, can capture the essence of even everyday objects—a slice of pie or cake, say—the way his mind’s eye can, in all of its luminous, numinous, buttercream-frosted glory.

Drawing from the Hockney-hued halcyon days of a childhood spent in Long Beach, California, Thiebaud’s luscious renderings of confectionery counters and the delights within are among his longest-running series, originating when he was a busy art teacher at Sacramento City College in the 1950s, where he landed after serving as a corporal in the Army during World War II. (While stationed at Mather Air Force Base, he created a comic strip, Aleck, for the base newspaper; as a high schooler, he apprenticed at the animation department for Walt Disney Studios.) In 1959, he married his muse, Betty Jean Carr, a filmmaker, and unveiled his first (and only) large-scale public installation, a 250-foot-long mosaic mural that adorned the then-new SMUD headquarters.

Joining UC Davis the following year as a founding member of its art department, Thiebaud found time to produce a bumper crop of new dessert-themed creations. His first brush with art world acclaim came in 1962, when the prominent Allan Stone gallery in New York displayed his now-iconic food paintings and his work hung alongside those by Andy Warhol, Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein and Ed Ruscha at the Pasadena Art Museum in a seminal group show titled New Painting of Common Objects, the first museum exhibition of Pop Art.

Except Thiebaud never cottoned to the Pop Art label’s cheeky irony. It’s a fair point. The charm of his work is the striking way he brings an Old Master’s command of light and texture to bear on subjects so soft and cheerful that they could serve as illustrations for a children’s book (as they have). Meanwhile Sacramento afforded him a quiet, idyllic life that helped keep the sugarplums dancing in his head. In 1971, he and Betty Jean, who passed away in 2015, bought a modest house in Land Park, where he still lives.

Four Pinball Machines fetched $19.1 million at a Christie’s auction in July. (© 2020 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY)

Fast-forward five decades, and the painter ranks among the top-selling living American artists, alongside names like Jeff Koons and Jasper Johns. Last November, the day before his 99th birthday, his Encased Cakes sold at auction for $8.46 million, setting a new record for his work. Only eight months later, that record was decisively shattered when Four Pinball Machines sold for $19.1 million at Christie’s.

This fall, to mark the artist’s centennial birthday (Nov. 15), the Crocker Art Museum will host Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings. The presentation, which is scheduled to run from Oct. 16 through Jan. 3, will fittingly consist of 100 works spanning more than 70 years, including classics like his landscapes of the Sacramento River Delta, streetscapes of San Francisco, and, of course, oils on canvas like Pies, Pies, Pies and Boston Cremes.

The display will also feature recent paintings depicting circus clowns, which the seemingly unaging nonagenarian started painting five years ago, reaching back into his memory bank to recall his childhood days when Ringling Bros. would come to town and he’d volunteer to work for tickets. (A full exhibit of this series is set to be mounted by the Laguna Art Museum from Dec. 6 through April 4.) Continuing the centennial celebration will be UC Davis’ intimate, teaching-oriented Manetti Shrem Museum, which will launch a group show in January highlighting the painter’s influence as an artist and educator, and featuring works by Thiebaud, as well as those by other artists and former students.

Pies, Pies, Pies (1961) will be among the classic dessert paintings displayed at the Crocker this fall. (Painting courtesy of the Crocker Art Museum, © 2019 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY)

“You do begin to see the world backwards,” Thiebaud told us in 2017, of being a person of a certain age. “You have a nice, rich bundle of thoughts and memories, and you think back to what it was like then, what marvels, what trepidations, all kinds of experience. Did we really do that? Was I really in the Army? Did I really make motion pictures? Did I work in the shipyards? Wash dishes? It’s a kind of wonderland, sometimes very strange.”

We reconnected with the Sacramento artist one afternoon in late July, talking to him by phone (he politely declined to Zoom it in) to catch up on life in the strange wonderland that he has long called home.

How have you been coping with the isolation of the pandemic?

My life hasn’t changed because I’m always working in isolation, so I’m one of the lucky ones. I play a little bit of tennis in the mornings two or three days a week. Then I work. That’s about what it is.

What are you working on now?

A series of mountain paintings. That’s going on for a period of about 20 years. I had an exhibition of them in New York last year. And then a series of paintings of clowns. I had an exhibition of those in San Francisco last year [at the gallery founded by his late son Paul, who died of cancer in 2010], and now it’s going to the Laguna Beach museum in October.

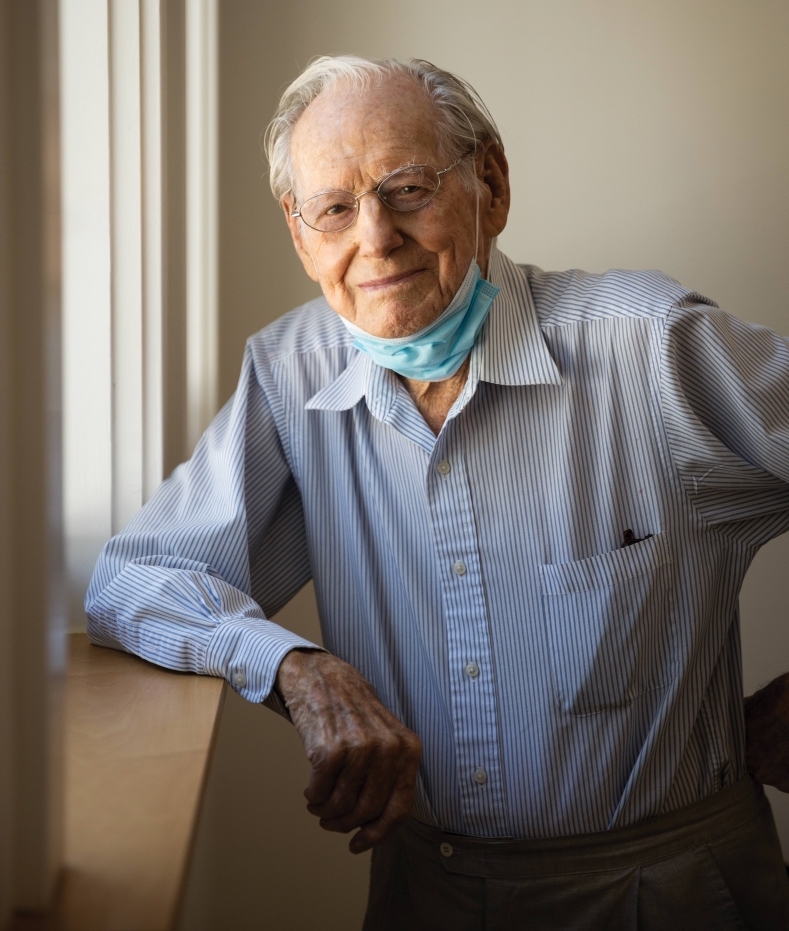

“I’m a mask guy,” Wayne Thiebaud said during a physically distanced photo shoot at his Sacramento studio on Aug. 11. (Portrait by Max Whittaker)

We will also see examples from this circus clown series at the Crocker this fall. What other exciting revelations can local museumgoers expect?

Paintings are not made to be exciting. They’re quiet little visual examples of poetry. So you can’t expect much excitement, but you can expect, I hope, a display of personal feelings. The Crocker show will represent almost all of the different subject matter and mediums—drawings, prints, watercolors, pastels, paintings and quite a variable number of things people have not seen because some of them have never been exhibited before.

Are there personal favorites of yours that people are going to see for the first time?

When I get that question, I like to tell a little story, if you don’t mind. Three daughters came to their mother and they asked, “Mom, which of us is your favorite?” And her answer was, “I dislike all of you equally.” And that’s my answer about the work. I like and dislike all of them sort of equally.

One of your “daughters,” Four Pinball Machines (1962), went for a pretty penny at auction in July. At $19.1 million, the sale more than doubled your previous record of $8.46 million, set just last November. What was your reaction to that particular development in your career?

My action/reaction to it is at least twofold: It’s something I’ve never cared about, never thought about and try not to think about now. Those are the kinds of things—fame and celebrity—that are pretty much beside the point of my direction or interests, which is a personal committed, struggling way of finding out about things in my own discipline, and loving corollary disciplines in the world of ideas and in the pursuit of excellence.

Three of the artist’s New Yorker covers, from left: Jolly Cones (2002), Hot-Dog Stand (2012) and Double Scoop (2020)

What do you remember most about painting that particular piece? Did it stand out to you at the time?

It was one of a series, and I usually work in serialization. The idea is an old, useful tool. Almost any painter takes a subject and then tries to orchestrate it in various ways. Monet painted the same cathedral over and over again, at different times of the day, in order to see what light did to it, and then what he could do in terms of taking a flat surface and seeing what could come out of that, how that subject matter might reveal itself. It’s a marvelous way of working.

When you do a series, there are ones that are more successful or interesting than others, but you tend to see them as a group, and that’s the case with the pinball machines. That painting was just one of six or seven different variations.

It’s all the same to me. Slot machines could be a series. Cakes. Gumball machines. All the subject matters have been amplified in a search for variation and interest.

Artists are addicted to a kind of personal exploration, and they’re highly neurotic. Those are the ways people in the arts go about their work. If they’re serious, if they’re committed, it’s a calling that’s personally rigorous.

The Laguna Art Museum plans to hold an exhibit of circus clown works by Wayne Thiebaud, including this 2015 painting. (Painting courtesy of the Laguna Art Museum, © Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY)

When we spoke last time, you said, “I feel awfully fortunate and more connected than ever to human beings and our plight. So I am certainly amazed and somewhat disquieted by what fearsomeness there is in humanism or lack thereof.” Three years later, do you see our current times as an exceptional moment? How do you see this moment in history?

I’ve always been committed to social consciousness and exploration. I hope this is a clear example of how we have failed, and to what extent we may regroup and rethink our positions, to evaluate and, with some dimension of clear thinking, find ways to improve ourselves and to make much more of a civilization and culture of sharing, of loving, of relating to each other in human terms. Of course, this is the charge of one of our great inventions, the university, which predicates itself on the humanities, as well as the sciences.

As an educator, do you think the pandemic-driven shift to remote learning will hurt us or make us more creative?

I’m not a good enough analyst on those terms. I’m an art teacher, and art would be very difficult to teach [online]. You need people to come together to share ideas. Imagine trying to teach life drawing online.

You settled in Sacramento early in your career as a teacher and painter. How has living here influenced your work?

Well, that’s a question which probably can honestly only be answered by saying that I don’t think it would matter that much where I was, as long as it offered the opportunity to have some sense of isolation and control over my environment, which Sacramento gave me. I had a great experience working first at the junior college [Sacramento City College] and then at the University of California at Davis, both of which offered me an education, because I’d not gone to art school. Teaching really became my education. So this community was very good for me, and people were very supportive very early on of [artists’] efforts as painters, sculptors and ceramists to support the Sacramento community. I’m very grateful for that, and very aware of the fact that Sacramento is really responsible for giving me a life that has been wonderful to participate in.

I still see quite a number of my former students—teaching was very important to me. I am primarily, in my mind, just an old art teacher. I’m just so interested in things like what makes a good painting, or even a painting of some consequence. And this kind of research is what enables any serious artist to engage, almost like a scientist. You do it primarily to find out something, to express something that hopefully hasn’t been expressed before, to give a sense of the expanding motion of what things are. So Sacramento is, overall, responsible for allowing me to do that.

Thiebaud working on his comic strip, Aleck, for the Mather Air Force Base paper in 1943 when he was a corporal in the U.S. Army. (Photo courtesy of Wayne Thiebaud)

If you were to give any advice to a young artist, or even to your younger self, what would that be?

I’d give the advice that I teach. The basis of that essentially is something they never want to hear, and that is to work your head off, and work harder than you think you need to work. Work when everyone else stops. The students who stay after class, who come on days when they don’t need to come, who do work outside, who ask more questions—those are the ones that are interesting. And that interest is what produces interesting work.

Speaking of working when everyone else stops, you did your ninth New Yorker cover last November, a Thanksgiving turkey for the magazine’s annual Food Issue. Will you be doing a 10th cover this year?

They have asked for another cover, which we’re in the process of thinking about and planning. It’s a pleasant aside. I’ve always loved The New Yorker and what it stands for, and I’m proud and flattered to be a part of that tradition, however small. [Editors’ note: This interview was conducted in July. Thiebaud’s Double Scoop, shown on the previous spread, graced the Aug. 17 cover of the publication.]

I tried to sell cartoons to The New Yorker for years, back when I was doing cartoons. And they never did accept any of them. Now it’s astounding that they put me on the cover! Talking with John Updike before he passed away, he had exactly the same experience. He was also a cartoonist, when he was at Harvard, and he sent in his cartoons and he told me they came back so quickly that he knew they didn’t even look at them.

Sliced Pie Stand depicts Thiebaud’s favorite pie: lemon meringue. (© 2020 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY)

With 100 years under your belt, do you have anything you want to do that you haven’t done yet? Do you have a bucket list? Do you have plans for celebrating your 100th birthday?

I don’t have a bucket list. I just have the interest that Matisse described—he said that work is a paradise. I don’t even know if I’ll have a birthday, first of all. I’ve already had 99 birthday celebrations, if you can imagine that. Ninety-nine sounded like a lot more years than 100 years, somehow.

Last question. Favorite flavor of pie?

The one my wife Betty Jean and I courted on—she made beautiful lemon meringue pies.