The Life and Deaths of Dorothea Puente

It’s been 20 years since Sacramento’s most notorious murderer, Dorothea Puente, buried seven bodies in the garden of her F Street boardinghouse. Now 80, she speaks out in a series of rare interviews on her crimes, her “relationships” with the Kennedys and the Reagans and why—in the end—the person she really wanted to kill was herself

The visitors hall at the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla brings to mind a church social as hosted for state convicts. Trapped by tan cinderblock walls that climax in a steepled ceiling, chatter and laughter create a kinetic mood amid the dense scent of microwaved pizza, burgers and fried chicken strips. Beneath the room’s ashen lighting stand neat rows of small round tables, some 50 in all. Ringed by four chairs, each serves as the setting of a reunion between a prisoner and those she knows from the outside.

An Asian woman in her mid-thirties, with sharp cheekbones framed by long glossy black hair, wears standard-issue prisoner garb: white T-shirt with long navy blue sleeves, dungarees and blue sneakers. On her lap bounces a pony-tailed girl in a red-buttoned vest who giggles “Mama!” Two tables over, a stout, fortyish black woman with a toothy smile banters with her parents and younger brother, to judge from the physical semblance. Behind them, a twentysomething blonde clutches the hands of a young man with a sun tattoo on his forearm. Sitting knee to knee, they stare without speaking, eyes wet.

I watch the scenes unfold from table No. 13, as designated by the plastic placard atop its faux-wood surface. I am not here to take part in a reunion; I have never so much as glimpsed the woman I am waiting to meet. I know her only through the words of others. I have read books and hundreds of news articles and file after file of court records related to her crimes. I have talked to her attorneys, to the cop who unmasked her, to the prosecutor who tried her for murder, to jurors who found her guilty. I have listened to the lingering grief and anger of a man whose mother died mysteriously while in her care. I have also done this: Late at night, when it is said her deeds turned darkest, I have pondered the vastness of human nature as I stood outside the tiny yard where she buried her victims.

I am waiting for one of the country’s most infamous female serial killers, an inmate whose notoriety leaves her without peer among women murderers in California history. I am waiting for Dorothea Puente.

* * * * *

If you lived in Sacramento in the late ’80s, you recognize her name. If you lived anywhere else, there’s still a good chance you recognize it, or at least the rough outline of her crimes. On Nov. 11, 1988, acting on the concerns of a social worker looking for a client who had disappeared, homicide detectives dropped by the man’s last known address: a boardinghouse for derelicts and the mentally ill that Puente operated at 1426 F Street, within a mile of the Hall of Justice and the Capitol. A search of the home showed nothing amiss. But a bit of digging in the backyard—a tenant had reported seeing large holes excavated and filled behind the house—unearthed a human leg bone and a decomposed foot.

The next day, under suspicion but not yet under arrest, Puente, then 59 and ostensibly the essence of grandmotherly virtue, fled the city. Police soon figured out why, uncovering the remains of six more bodies. Some were in an almost mummified state, wrapped tight with cloth, bed sheets and duct tape. One was missing its head, hands and feet.

The four women and three men, ages 52 to 79, had boarded at the two-story, powder-blue Victorian. Several were referred there by social workers who viewed the home as a last-resort refuge for their ailing or most erratic clients. Police later accused Puente of lacing food or drinks she served her victims with a lethal mix of prescription drugs, poisoning them to collect their Social Security checks, a scheme that netted more than $5,000 a month.

Dorothea Puente at the Central California Women’s Facility, February 21, 2009 (Courtesy of Central California Women’s Facility)

Her escape intensified interest in a lurid tale that for a time made Sacramento the center of the media universe. Coverage spanned from the national networks and Time, Newsweek and The New York Times to the National Enquirer, National Examiner and news outlets from as far away as England and France. As police exhumed corpse after corpse, TV crews jammed F Street while gawkers scaled trees to peer into the yard. Puente’s neighbors and acquaintances murmured disbelief that the white-haired landlady who handed out homemade tamales and fussed over her rose beds and vegetable garden could be a mass murderer. Well regarded for taking in substance abusers and the homeless, she had earned respect in political circles for her charity work. Scattered about the house were photos of her with the likes of California governors George Deukmejian and Jerry Brown, who once danced with her at a fundraising ball.

Puente’s vanishing ignited a manhunt that stretched to Mexico. Finally, four days after she skipped town, authorities traced her to a tumbledown motel in Los Angeles. Yet for all the local, national and international coverage of the bizarre case in ensuing years, the public heard virtually nothing from its main character. In 1993, facing nine counts of murder after prosecutors linked her to two other deaths, she stood trial without testifying. After what was then the longest deliberation in a murder case in state history—24 days—the jury convicted her of three killings. She received a life sentence without possibility of parole, and as before the trial, she granted few interviews in its wake, observing a self-imposed gag order. Familiar in name, she remained an enigma.

So when I wrote to Puente last summer, nearly 20 years after the discovery of her victims, I had little expectation she would respond, let alone agree to talk. The impending anniversary, if tracked only by media types and those who sell serial-killer novelties online, had stirred my curiosity. I wondered how the last two decades had changed her, how she had endured. I wondered if she maintained her innocence or felt bowed by remorse. I wondered whether, when thinking back to 1988, she saw her past as her own or that of a different Dorothea Puente, one who, over time, had faded into something of a stranger.

To my surprise, an envelope stamped with the words “Central California Women’s Facility State Prison” arrived a few weeks later. In her note, written on plain lined paper in a grade-schooler’s swirling cursive, she invited me to visit. After I cleared the prison’s background check, we arranged a date in mid-October; an early riser, she told me she preferred to meet in the morning. Waking at 5:30 a.m., I drove 135 miles south to Chowchilla, slowed by low-hanging fog as opaque as her reasons for ending years of public silence.

Now, as I sit at table No. 13 and watch the prison’s visitors hall gradually fill, my doubts that she will appear grow with the room’s din. Inmates enter one at a time at irregular intervals through a gray metal door along the rear wall. Again and again, it is not her. As the minutes pass, I prepare to join the long list of people she has duped. She never intended to show, I realize. The joke’s on me. I scan the room out of empty impulse, certain I haven’t missed her.

That’s when the gray door clanks open once more.

* * * * *

The serial killer shuffles into the room with a chicken’s hitched gait. Her body shapeless under a long-sleeve T-shirt and dungarees, she has pulled back her snowy plume of hair with a pink scrunchie. She moves toward the front of the room, where a guard seated behind a metal desk tells her my table number. I rise as she approaches and shake a hand that feels skeletal and small. Her narrow lips, pinched and lined at the corners, curl slightly upward. Time has deepened the creases between her potato-like nose and dumpling cheeks, and her blanched skin has slackened at the neck. Round-framed glasses too large for her face magnify a pair of pale blue eyes. She resembles a wizened owl.

We break the ice. I talk about the foggy drive to the prison, she recounts her trip to the visitors hall. “It’s about a mile from my building to here,” she says. “I get pushed in a wheelchair.” She speaks in clipped sentences, her voice, so rarely shared with journalists, scratchy but strong. The conversation soon veers toward why I want to interview her, and before I finish explaining, she interrupts. For the first time, her gaze squarely meets mine.

“I’m not guilty.”

The visit was my first of six with Puente, who turned 80 in January. We next met days before Thanksgiving, when the recent election of Barack Obama had boosted her hopes for the country’s future, and again in mid-December. After spending part of Valentine’s Day with Miss Dorothea, as other inmates call her, I returned later in February and stopped by for a final chat in April. During discussions that typically lasted two to three hours, she proved by turns defiant and self-pitying, disavowing she killed anyone while reserving words of sorrow for herself.

“They don’t have all the facts,” she tells me one morning, dismissing those who judge her a murderer. “They’ve never talked to me.” On another occasion, she casts her circumstance in a biblical light. “I don’t think anyone would pick this kind of life,” she says, drying tears with a piece of coarse brown paper towel. She folds the towel several times into a tight square before clasping her hands together on her lap like a child attending Mass. “But God always puts obstacles in people’s way. Look at Job, John, Paul, Moses. Things happen for a reason.”

Nov. 12, 1988: Homicide detective John Cabrera (right) ushers Puente out of her home to a nearby hotel. She would flee the city that morning. (Courtesy of The Sacramento Bee/Genaro Molina)

I ask why she’s here. “To give strength to other people.” She lifts the paper towel to her eyes.

Puente arrived at the Central California Women’s Facility following her conviction in 1993, and her appeals expired early last year. Barring an unexpected transfer to another prison or a medical emergency, she will die inside this compound. “I’ve given up hope of getting out,” she says. “But you gotta do something so you don’t go crazy.”

Driven by routine, Puente rises by 4:30 a.m. most days, long before her seven cellmates. They share a gray cinderblock room furnished with eight metal lockers, four slender bunk beds, two sinks, a toilet and a shower. Drab and worn, the space, about the size of a single-car garage, has scuffed concrete flooring, dull fluorescent lighting and two windows; one faces a grassy prison courtyard, the other an interior hallway. It is a stifling backdrop in which to live out the years.

Puente occupies a lower bunk owing to her age and tenure at the prison, sleeping on the same kind of thin, lumpy mattress as other inmates. In her telling, after showering and dressing, she prays, recites the rosary and reads a few pages of the Bible, favoring Proverbs and Romans. (To the question of which verse most resonates with her, she shrugs and replies, “All of ’em.”) She then quietly gathers the clothing of her slumbering “roomies” to wash later in the morning, when prisoners are allowed out of their cells. As the others begin to stir, she tidies up the space, a boardinghouse landlady to the last.

Inmates eat breakfast and dinner in a dining hall separate from their building units; after breakfast, they receive a cold boxed lunch that they take back to their cells. To vary her diet, Puente sometimes cooks in her room, making tamales with tortillas, canned chili, cheese and other ingredients bought in the prison’s canteen or mail-ordered through a food-delivery service. (A charity she declines to name sends her $15 a month, her sole source of money.) She steams the tamales in plastic bags placed in a pan of water warmed with two electric immersion coils. “The guards will come by and go, ‘What you got cooking today?’ ”

She marks much of the day reading mind-candy fiction—she’s a fan of John Grisham and Dan Brown—and watching TV; her favorite prime-time shows include CSI, Criminal Minds and Cold Case. All three revolve around murder, a fact she notes without irony or self-consciousness. She attends services held at the prison’s chapel, but avoids joining inmate worship groups. “I don’t feel like confessing my sins to anyone,” she says sharply. “That’s between me and my God.”

Until 2006, Puente rotated through assorted prison jobs, cleaning cells, giving haircuts, toiling on a landscaping crew. With age and health concerns relieving her of work duty, she considers her self-assigned morning chores, attending chapel and other diversions a means of survival. “A lot of people get old in here really quickly ’cause they just kind of stop doing anything.”

Ruth Munroe, believed by authorities to be Puente’s first victim (Courtesy of The Sacramento Archives)

The subject of personal health preoccupies Puente as much as the next octogenarian. To reduce chest pain, she wears a nitroglycerin skin patch. She reveals as much when, unbidden, she yanks down her shirt collar, baring a white patch the size of a silver dollar stuck to ghostly blue-veined flesh. For my benefit, she recites her prison medical history: a tumor removed from behind one knee last year; angioplasty in 2003; repair of a ruptured artery in 1998. She also mentions undergoing major cancer surgery in 1961 to remove her reproductive organs and part of her intestines and stomach.

Federal law shields inmate medical records from the public, leaving open the question of whether she has had three surgeries since entering prison. Her cancer story, on the other hand, sounds consistent with her peculiar, decades-long charade of claiming to suffer from the disease in a ploy to gain sympathy. In any case, after more than 20 years behind bars, and despite the withering of her features, she retains a physical vitality and a fondness for cosmetic excess. She tends to wear thick violet eye shadow and pink lipstick, both of a hue common to Toulouse-Lautrec paintings, and her body lotion of choice, Victoria’s Secret Love Spell, gives her the subtle bouquet of cherry blossoms.

Still, prison has changed Puente in one profound aspect, reforming her into an obedient citizen. In 16 years at the facility, she has accrued only two rules violations, the last occurring in 2004. (Details of reports on such incidents are not public record.) A prison official describes her as “very low-key, very quiet.” If discreet, however, Puente, who stands 5-foot-3, bears an outsized notoriety. “The inmates know who she is,” the official says. “They know what she’s done.”

Puente conveys a pride in her renown that, now and then, gives way to embarrassment, or perhaps weariness. “Everybody’s heard of me. They all know who I am,” she says. She sits erect, legs crossed at the ankles and tucked beneath her chair. “There’s a waiting list of people who want to be in my room.” (This is true in the broadest sense: The prison’s population hovers around 4,000 from month to month, roughly double its capacity. In effect, every cell has a waiting list.) On a subsequent visit, her vanity recedes when a guard, apparently new to working the visitors hall, asks her name. In a low, almost plaintive voice, she replies, “Puente. No one else would want that name.”

Prison protocol bans inmates from talking to each other in the hall apart from brief exchanges. During my meetings with Puente, a number of prisoners softly greet her—“Hi, Miss Dorothea”; “How are you, Miss D?”—as they walk past. Some touch her shoulder. Others wave and smile. She tells me they appreciate the advice she provides them, whether informal legal counsel on their cases or how to traverse the social services network after their release. And, she says, “They like my tamales.”

Her shoulders shake as she laughs, her open mouth exposing a white flash of dentures. It occurs to me that if I were unaware of her past and talking with her outside of prison, she could come across as the little old lady next door. When we discuss her health or the books she reads, when she makes a rare inquiry about my job or background, the conversation tracks as normal, even mundane. She does not smile, laugh or joke much in my presence, but nor does she betray malevolence. Her demeanor is, for the most part, politely docile, and I begin to perceive how so many could consider her trustworthy. Her passivity subdues suspicion. She seems entirely harmless.

Throughout our meetings, Puente furtively points out inmates and comments on their crimes. “See that one?” she asks, nodding toward a gaunt, gray-haired woman with stooped posture. “She’s dying of cancer. Been here 27 years. She killed her husband after he abused her and her kids.” A Latino woman with shoulder-length dark hair passes our table and whispers hello to Miss Dorothea. “She’s been in for 12 years. She got life for being with a guy when he killed another guy,” Puente says. She falls silent for a moment. “There are so many sad stories in here. A lot of women shouldn’t be here.”

She counts herself among them, even while conceding few people believe in her innocence. As we continue talking, the topic switches to her life before prison, and I ask what she misses most about Sacramento. She answers without pause. “Going to church every day. Cooking what I want. Working in my yard.”

When we later part, Puente disappears through the gray metal door at the back of the hall. I leave through a different door and make my way out of the prison, stepping into the cool afternoon air. Her words return to me. Working in my yard.

* * * * *

The three men carried shovels as they fanned out across the backyard of the two-story Victorian at 1426 F Street. John Cabrera and Terry Brown, homicide detectives with the Sacramento Police Department, and Jim Wilson, a federal probation agent, had arrived at the house late on the morning of Nov. 11, 1988. They first spoke with Dorothea Puente, who ran the clean, cozy home as a boardinghouse for low-income tenants. Now she watched from her second-story porch as the trio began to dig.

Their first series of holes dislodged only soft dirt and a vague sense of futility. But while digging a second hole, Wilson heard a muted thud as his blade struck something hard three feet down. He called over Cabrera and Brown, and after he scooped away more soil, they saw what resembled a tree root. When attempts to extract it with a shovel failed, Cabrera climbed into the hole. Setting his feet, he grabbed hold of the object and, with a violent jerk, loosed it from the earth’s grip. His eyes popped wide.

“It was a human leg bone,” he recalls. “I could see the joint.”

Cabrera scrambled out of the hole, pulse rate and thoughts quickening. The three law officers had stopped by the house to try to learn the whereabouts of Alvaro “Bert” Montoya, who had gone missing three months earlier. A gentle bear of a man, the 52-year-old Montoya suffered from untreated psychosis, a condition that for years had consigned him to the streets and homeless shelters.

Puente had welcomed him into her home that February. At the time, she owned a solid reputation among Sacramento’s social workers, who referred clients to her that other boardinghouses turned away: the mentally ill, recovering alcoholics and drug addicts, those with chronic physical maladies who had no one to care for them. They were men and women who had skidded toward life’s edges. Puente offered a place where they could hang on.

Given Montoya’s history as a transient, his disappearance would have escaped notice without the persistence of Judy Moise. An outreach counselor with Volunteers of America, she had visited Puente before placing him in her care. In October 1988, discovering he no longer lived at the house, Moise began to hound Puente about his departure. Her evasive answers—first claiming he had traveled to Mexico, then that he had returned and moved to Utah—tripped Moise’s suspicion. She filed a missing person report with police on Nov. 7.

An officer dispatched to the house that morning interviewed Puente and one of her tenants, John Sharp. In the landlady’s presence, he corroborated her story about Montoya. But before the cop left, Sharp managed to slip him a hand-written note that read, “She’s making me lie for her.” He later divulged unsettling details about life at the house.

Some months earlier, another tenant, a longtime alcoholic on a bender, had vanished after Puente went to his room to “make him feel better.” The acrid stench of rotting flesh soon spread through the home and beyond, an odor she blamed on sewer problems and that drew complaints from neighbors. Sharp also told police that Puente had hired prisoners on work furlough to dig and fill large holes in the backyard, and that some of the holes were covered with concrete.

The Montoya file landed on Cabrera’s desk within a day. A year earlier, he had probed the case of Morris Solomon, a Sacramento handyman who would be convicted of murdering six women across the city. The detective had yet to realize that, in the 59-year-old Puente, he had another serial killer on his hands. What he did know was that her public image as a shepherd of the dispossessed veiled the past of an ex-con who preyed on the weak.

* * * * *

The noise inside the prison’s visitors hall amplifies on Valentine’s Day. The higher volume results from the presence of more children, most of whom exhibit the happy symptoms of a sugar buzz. In addition to the usual fare sold in the hall’s chow line, there are heart-shaped boxes of chocolates for $7. The candy proves popular with youngsters, whose sporadic laughter pierces the room’s hum. Some play Scrabble, Sorry! and other board games that the prison makes available to visitors. A few wander over to a colorful mural of Winnie the Pooh, Eeyore, Tigger and Piglet, who prance beneath a banner reading “Family Is Love, Love Is Family.” None of the kids acts bothered that mom or grandma or big sister is doing time.

I have arrived seeking to somehow pierce Puente’s carapace of denial, to find a crack or contradiction in her answers that might expose her deceit. But in truth, I approach this task without optimism, anticipating that our meeting will stick to the pattern of previous visits. Questions about her criminal record will elicit short answers trailed by awkward silence, during which she will stare at the table or the far wall, in the direction of Winnie and friends. On subjects unrelated to her misdeeds, she will open up, weaving anecdotes that are sometimes embroidered, sometimes made from whole cloth.

Today she repeats a tale she first spun for me three months ago, showing remarkable fidelity to the specifics of the earlier version. As the story goes, while shopping at a department store called The Emporium in San Francisco in 1948, a 19-year-old Puente felt a tap on her shoulder. A man identifying himself as a talent scout for the Radio City Rockettes, the famed New York City dance troupe, sized her up and, on the spot, invited her to fly east for an audition.

Despite lacking formal dance training, she says, “I went out there and they hired me. So after that, I was out in New York on Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, and then I’d come back to California the rest of the week.” Known at the time as Dorothea McFaul, the last name of her first husband, whom she had recently divorced, she performed on stage as Sharon Neyaarda. She balanced her dance career with a second job as a cook at a San Francisco seafood restaurant, she tells me, shuttling between coasts until her dance career came to a sudden end in 1957.

“I was on stage when the girl next to me broke her heel and bumped into me. We both fell into the orchestra pit and I broke my leg.” The other dancer? “She was paralyzed.” (The Rockettes’ alumni association has no record of someone named either Sharon Neyaarda or Dorothea McFaul performing with the company, nor of two dancers tumbling into an orchestra pit.)

Puente relates that, as a Rockette, she met John Kennedy, then a U.S. senator, and his wife, Jackie, and befriended actress Rita Hayworth. They belong to a litany of famous names she drops during our meetings. Most of the luminaries are connected to her years in Sacramento, where she moved in the mid-’50s with her second husband, Axel Johansson, who now lives in Orangevale. “He’s the brother of Ingemar Johansson, you know,” she says, referring to the late heavyweight boxing champ. (Obituaries for Ingemar Johansson, who died earlier this year, list his sole surviving brother as Rolf.)

Axel Johansson rates as Puente’s favorite of her four ex-husbands, a presumably unwanted distinction. Her warmth for him appears unrequited—she hasn’t heard from him “for awhile now”—and reflects rose-tinted nostalgia for a marriage that, despite near constant turmoil, lasted longer than her other three combined. It is a wistfulness that lays bare the depth of chaos that defined Puente’s status quo long before they married in 1952.

* * * * *

Dorothea Helen Gray met the world on Jan. 9, 1929, in Redlands, Calif., the sixth of seven children born to Jesse James Gray and Trudie Gray. In the narrative of her life that unfurled at her murder trial and in news reports and books about the case, she grew up poor, deprived in equal measure of material comforts and parental nurturing. Her father died of tuberculosis when Dorothea was 8; her mother, an alcoholic who alternated between abusing and deserting her children, lost custody of them in 1938. She lost her life in a motorcycle wreck the same year, orphaning Dorothea before she turned 10.

Through her early teen years, young Dorothea found herself handed off to a series of relatives and foster homes, bouncing between Napa and Los Angeles, court records reveal. At age 16, she drifted off on her own to Olympia, Wash. Comely and flaxen-haired, with soft blue eyes and a beguiling smile, she worked as a prostitute to earn money and caught the attention of Fred McFaul. A 22-year-old soldier who had returned to the U.S. from the Pacific after World War II, he married Dorothea in 1945, and they moved to Gardnerville, Nevada to start a family.

Domestic bliss and her maternal instinct failed to take root. She gave birth to a daughter in 1946 followed by a second less than a year later, but public documents suggest she inherited her mother’s aversion to childrearing. One girl was placed in the care of relatives, the other put up for adoption. (Puente tells me she also had twin daughters who as young adults committed suicide one week apart. She declines to disclose the father’s name, when and where they were born and died or the circumstances of their deaths.)

McFaul split from his young wife in 1948. Later that year, Dorothea moved to San Bernardino and picked up her first criminal conviction after trying to float a check under a false name. She wound up serving four months in jail and shortly afterward fled Riverside County, flouting the terms of her probation. By 1952, she had wed Johansson, whom she met in San Francisco.

The couple moved to Sacramento a short time later and lived in the city off and on for the next decade. Frequent quarrels and separations marred the marriage, with much of the discord brought on by Dorothea’s appetites for drinking, gambling and other men. Court files indicate Johansson had his wife committed to a psychiatric ward in 1961, and doctors placed her on antipsychotics.

The hospitalization occurred a year after Sacramento police busted Dorothea in a raid on a residential “house of ill fame” on Fulton Avenue that had fronted as a bookkeeping service, according to court records. An undercover cop posing as a trucker arrested her after she offered to perform fellatio on him; she served 90 days in county lockup. My question about the incident draws an explanation akin to the one Puente gave a county judge nearly a half century earlier: “I was there visiting a friend when the cops came.” She refuses to elaborate.

Johansson divorced Dorothea in 1966. She claims he has sent her Christmas cards in prison, and as she talks about that small act of kindness, her eyes mist over. “He was a good-hearted man, very kind,” she says. “He was good to me.” (Johansson did not respond to interview requests.)

Hard living had stolen much of Dorothea’s youthful beauty by the time she landed her third husband in 1968 and settled in Sacramento. At 39, she was 16 years older than Roberto Puente, a Mexican émigré whose interest in his heavyset bride concerned “money and American citizenship,” as chronicled in Disturbed Ground, a 1994 book about the Puente murder case. They separated in 1969, and not long after, Dorothea, who had briefly run an unauthorized rehab program for alcoholics, opened a boardinghouse at 21st and F streets.

The unlicensed venture thrived from the start. She parlayed its success by pumping money into political campaigns and charitable causes, contributions that bought her the appearance of legitimacy and access to elite circles. Puente claims she spent time in the ’70s with California governors Pat Brown, Jerry Brown and Ronald Reagan. She recalls the future president and his first wife, Jane Wyman, as her “good friends.” When I mention the Gipper’s second wife, she frowns. “Me and Nancy,” Puente says, shaking her head, “we never got along.” (A similar epitaph could apply to her marriage to her fourth husband, Pedro Montalvo, who left her in 1976, the same year they exchanged vows in Reno.)

Thanks to her ties to Reagan, Puente tells me, she met Vice President Spiro Agnew and U.S. Sen. Alan Cranston, and in the mid-’70s, she ate dinner with longtime Republican booster Clint Eastwood when he visited town. With a smile, I ask whether she and the actor shared a romantic attraction. She answers with a look of mild reproach that pulls taut her soft fist of a face. “He was going with another movie star,” she says. “He’s not a flirt.”

At the time of her 1988 arrest on murder charges, photos of Puente with Jerry Brown, former California Gov. George Deukmejian and Bishop Francis Quinn decorated her home at 1426 F Street But setting aside such fleeting charity-event encounters, her stories hew closer to fable than fact. Scant evidence exists to suggest she socialized with Reagan—when he divorced Wyman, Puente was 20 years old and living in the Bay Area—any more than she danced with the Rockettes. Her memories, I come to understand, blend rote recitation of illusory events with blatant omission of her crimes.

In the ’70s, while running her first boardinghouse at 21st and F streets, Puente cultivated a strong rapport with social workers. They prized her willingness to accept alcoholics, drug addicts and other difficult clients into her home, a sprawling, three-story Victorian that could sleep more than two dozen tenants. The business supplied her with steady revenue—steady and, apparently, inadequate. Her upstanding reputation concealed a habit of forging the signatures of tenants on their benefits checks before signing them over to herself. The erstwhile prostitute had turned a new trick. Arrested for the scam in 1978, court records show, she received five years’ federal probation, the terms of which proscribed her from operating a boardinghouse.

Over the next few years, she adapted by working as an in-home caregiver, affecting a matronly mien with her modest dress, oversized glasses and tremulous voice. She inflated her age by 10 to 15 years to further disarm her elderly clients, whom she set about exploiting under the guise of ministering to them. Puente drugged three women with tranquilizers to steal checks, money and valuables from their homes in the early ’80s, as recounted in court records. Around the same time, she slipped a heavy sedative into the drink of a 74-year-old man she met at the Zebra Club in midtown. When they returned to his apartment, he watched in a stupor as Puente helped herself to his checks and cash; before leaving, she slipped a diamond ring off his pinky.

The string of thefts led to her arrest, and in 1982, a Superior Court judge sentenced her to five years in prison at the California Institution for Women in Corona. Released after three for good behavior, she returned to Sacramento, with her federal probation extended to 1990 due to the state conviction.

The house at 1426 F St., where police found seven of Puente’s tenants buried in the yard, as it looks today. Her bedroom was on the second floor. (Photo by Jeremy Sykes)

As we talk on Valentine’s Day, I broach her long-ago brushes with the law, only to find myself stymied again. Puente’s mechanical response echoes what she has told me during prior meetings, and what I will hear on subsequent visits. “Those cases were lies,” she says, voice flat. “I didn’t drug anyone. I’m not that kind of person.” I prod for more, to no avail. Her eyes fix on the mural of Winnie the Pooh.

Prison persuades some inmates to repent, their perspective evolving with time as they forsake their younger selves. For Puente, the distortions of her past have congealed into a personal reality that grows ever more fanciful. On a later visit, she brags that she won $10,000 on a 1950s game show on NBC called Feather Your Nest; another time, that she played a few tournaments on the fledgling LPGA tour in the ’50s. I inquire how she juggled the demands of professional golf with her Rockettes career while flying between San Francisco and New York every week. “I just did,” she says.

We lapse into a short silence, and in that span, the incredible feats of a younger Dorothea diminish in the distance. The unreliable narrator breaks the hush. “Since I’ve been in here,” she says, “it’s like all of that never happened.”

* * * * *

A state psychologist who evaluated Puente before her release from prison in 1985 diagnosed her as schizophrenic. “This woman is a disturbed woman who does not appear to have remorse or regret for what she has done…,” he wrote. “She is to be considered dangerous, and her living environment and/or employment should be closely monitored.” The following year, without a license and in violation of her federal probation, she opened a boardinghouse at 1426 F Street, with enough space for as many as eight tenants. Federal probation officers visited her numerous times in the next two years without suspecting she ran a business, lulled by her kindly facade and clean home as much as by her lies that those staying at the house were friends or guests.

The psychologist morphed into a prophet with the discovery of seven bodies in Puente’s backyard in November 1988. Authorities alleged that, by poisoning her boarders, she wanted to collect their benefits checks without risk of them notifying social workers or police.

The theory, while perhaps logical to anyone unfamiliar with Puente before her name hit the headlines, brought disparate reactions from those who already knew her. They described a woman of contradictions. Some praised the soft-hearted landlady who cooked big meals for her low-income tenants, handed out vegetables from her garden to neighbors and adopted stray cats. Others disparaged the closet alcoholic who on occasion punctuated roof-raising, cuss-filled tirades with a piece of furniture heaved down the stairs. Some lauded the tireless advocate whose charitable work benefited the Hispanic community. Others spoke of a calculating criminal who feigned altruism to mask her avarice—and a homicidal bent.

Retired social worker Mildred Ballenger first met Puente in the late 1970s. Then working as an in-home caregiver, Puente displayed an odd obsession with her own health, lamenting to clients and caseworkers alike that she suffered from cancer. “But every time you’d go to see her,” Ballenger says, “her cancer had moved from her brain to her breast to her liver. It was always moving. So you knew she was a liar.”

Ballenger began to suspect Puente of more nefarious behavior after learning that two elderly women in her care had suffered recurring spells of illness that baffled doctors. Tests revealed high levels of unprescribed drugs in their systems, and in time, the physicians fingered her as the culprit. (One woman later discovered checks and jewelry missing from her home; her case played a part in Puente’s 1982 arrest on theft charges.) An alarmed Ballenger urged fellow counselors to steer clear of Puente. Most disregarded the warning in the face of a paucity of housing options for alcoholics, drug addicts and the mentally ill, and even after her release from prison in 1985, social workers and homeless advocates, ignoring or unaware that she was an ex-con running a boardinghouse without a license, sent their clients to her.

“She was just pure evil,” Ballenger says. “I don’t know that she ever did anything good without a bad motive.”

A contrary perception derived from Puente’s strong ties to Hispanic residents living in downtown and midtown. Though born in Redlands, Puente, who speaks passable Spanish, claimed Mexico as her birthplace, a ruse she perpetuated by alternately using the surnames of her last two ex-husbands, Roberto Puente and Pedro Montalvo. She donated to Hispanic arts and education programs while providing cheap medical care to her boarders and other “patients,” falsely claiming she had worked as a nurse in World War II. (She garnished her war story with accounts of surviving the 1942 Bataan Death March, a lie she repeated to The Sacramento Bee in a 1982 article on the march; in truth, she was 13 years old and living in California at the time.) Her goodwill earned her the honorific title la doctora and flattering write-ups in local Spanish publications.

“She was a respected figure to the Mexican community,” says Donald Dorfman, a longtime Sacramento criminal attorney who handled some of Puente’s legal affairs before her 1988 arrest. “She gave them clothing, she gave them food. She’d give advice to all these young Mexican women who came to her when they were trying to get divorced.”

Puente poses next to California Gov. George Deukmejian (second from left) in this undated photo. (Courtesy of The Sacramento Archives)

Dorfman drew up Puente’s will years ago—“I don’t know if it’s any good anymore; she’s probably given away stuff she doesn’t [even] own”—and still receives Christmas cards from her. He remains convinced of her innocence, arguing that her crimes were limited to filching the benefits checks of her tenants. “I’m certain they were just dying of natural causes, and she started burying them so she could keep the checks coming. This was a money-making scheme, but I do not believe she was a murderess.”

For William Clausen, by contrast, the bodies buried in Puente’s yard confirmed what he already considered fact: she killed for profit. In late 1981, his mother, Ruth Munroe, went into business with Puente, leasing and running the restaurant side of the Round Corner Tavern in midtown. The next spring, with her husband hospitalized by terminal cancer, the 61-year-old Munroe moved in with Puente to save money. Within two weeks, Munroe fell ill, her body so weak she struggled to stand.

Clausen checked on her in April 1982 and saw his pallid, suddenly enfeebled mother, who rarely drank alcohol, sipping crème de menthe. “She told me Dorothea had given it to her to help calm her down,” says the 55-year-old Clausen, who runs a furniture upholstery shop in South Land Park. “That didn’t seem right, but Dorothea had conned our whole family into thinking she was a nurse.”

Four days later, Munroe died at Puente’s home. Her rapid decline perplexed her loved ones until they read the coroner’s report: the death was labeled a suicide caused by an overdose of codeine and acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. The family suspected Puente of poisoning her. Their theory hardened into subjective truth when they discovered that, following the funeral, the “nurse” had drained thousands of dollars belonging to Munroe from a joint business bank account.

In summer 1982, Clausen and his siblings spotted a story in the Bee about Puente’s conviction on theft and forgery charges related to her drugging four elderly people. They appealed to authorities to reexamine their mother’s death, a probe that ended with investigators upholding the suicide ruling. Only after unearthing seven corpses at 1426 F Street in November 1988 would prosecutors charge Puente with killing Munroe. “If she had been held accountable for murdering my mother,” Clausen says, “then maybe there wouldn’t have been any other victims.”

* * * * *

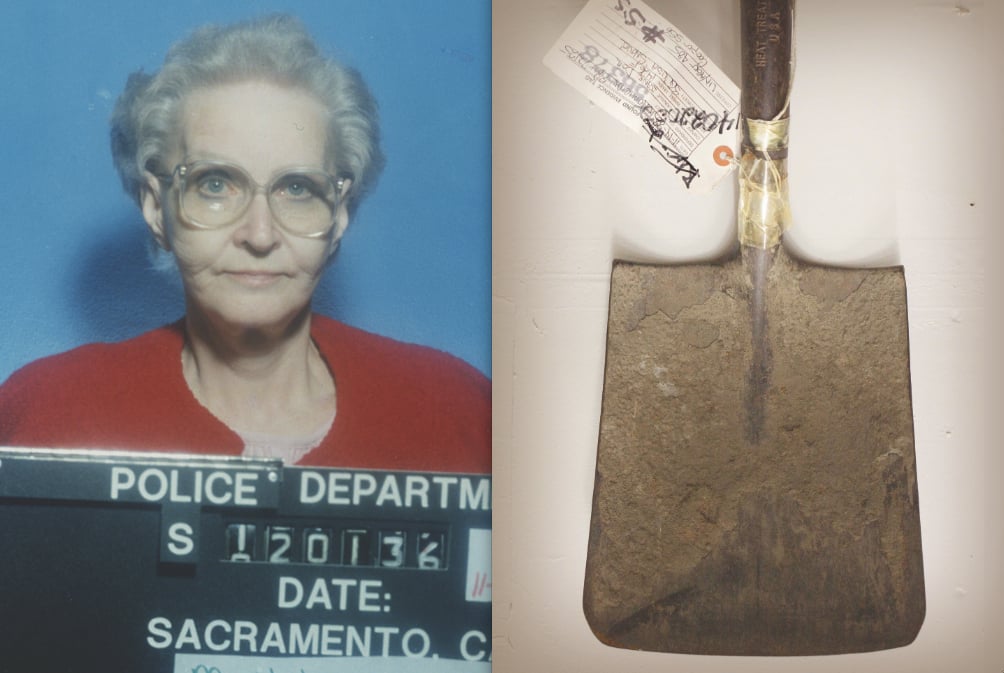

John Cabrera sits at a long wooden conference table inside Sacramento Police headquarters on Freeport Boulevard. Artifacts from the Dorothea Puente case splay out before him: a faded article published in a local Spanish newspaper with a black and white photo of a younger Puente; a pair of her mug shots, blue eyes dimmed and weary in both; a prescription label in her name for diazepam, a tranquilizer sold as Valium; the original wanted bulletin from Nov. 12, 1988, the day she went on the lam.

Beneath a black and white mug shot of Puente wearing a polka dot dress and round glasses, the bulletin reads, “The above suspect wanted for murder after several bodys (sic) found buried in her backyard. Suspect left her residence for a walk but never returned.”

Puente had stayed poised a day earlier when Cabrera showed up with a fellow homicide detective and a federal probation agent. They wanted to question her about Bert Montoya, her onetime tenant who had been reported missing. She stuck to her story that he had left for Utah after a trip to Mexico, and agreed to let her three visitors search the two-story house. When they finished without noticing anything suspicious, Cabrera asked if they could dig in her yard. She consented again, even lending a shovel to the men, who had brought only two.

Cabrera, lead detective on the Puente case, stands with the shovel that she lent to law officers to dig in her backyard on Nov. 11, 1988. “A person like her,” the retired sergeant says, “there’s no forgetting.” (Photo by Jeremy Sykes)

As it happened, her shovel was used to dig the hole that yielded a human leg bone, a decomposed foot inside a dark dress shoe and what looked like pieces of tattered fabric that in fact were rotting flesh. The discovery prompted Cabrera to summon Puente to the backyard. She gasped at sight of the remains, hands bracketing her cheeks. “I don’t know what to tell you,” she said.

Today the 59-year-old Cabrera works cold cases for the department as a retired sergeant. Two decades after he yanked the leg bone from the ground behind the boardinghouse, his dark hair has shaded silver and he has shaved off his boomerang-curved mustache. Unchanged are his lean, square-shouldered build and animated manner, his eyebrows spiking and hands windmilling as he recounts the investigation. High-profile cases dotted his career, including those of convicted mass murderer Morris Solomon and the Unabomber. But Puente has lodged in his psyche as the rarest predator he confronted: in age, gender and disposition, she inhabits an extremely narrow strata of serial killers. “A person like her,” he says, “there’s no forgetting.”

The initial jolt of uncovering a dead body on Nov. 11 ebbed as Cabrera weighed three factors. Old bones sometimes turned up in downtown and midtown yards, vestiges of the early 20th century, when families unable to afford a cemetery plot interred loved ones on their property. The advanced state of decay, meanwhile, suggested the person had died long before Montoya’s presumed disappearance in August.

Then there was the riddle of Puente. Slight and demure, with her ivory-white hair and solicitous demeanor, the landlady resembled any other elderly woman with a kitchen full of pots and pans and a cat calendar hanging next to the stove. She had breached her federal probation by running a boardinghouse, yet admitted to the offense when asked. Her past crimes belied her pose of pure benevolence, yet she had submitted to the house and yard searches without protest.

In the end, Cabrera erred on the side of skepticism. He ferried Puente to police headquarters and grilled her for two hours. She parried, unwavering in her account of Montoya’s departure, her voice calm as the detective pressed her. “Sir,” she said, “I have not killed anybody.” She explained that she had buried excess trash in the backyard holes that a tenant mentioned to police, and covered some of them with concrete to stunt weed growth.

“I started working her,” Cabrera says, “but all along, she was working me. She was tough. She never blinked, never broke a sweat.” After the interview, he allowed her to return to the house, where a patrolman stood sentinel outside through the night.

Working in my yard.”

Police and forensics experts swarmed Puente’s property the next morning. She watched from her porch, and before Cabrera put spade to soil, she requested a moment of his time. Speaking softly, she asked, “Am I under arrest?” When the detective told her no, she explained that the police presence and the growing mob of onlookers had her on edge. To soothe her anxiety, she wanted to walk to the nearby Clarion Hotel with one of her boarders to meet her nephew for a cup of coffee.

Cabrera’s superiors approved her request, deciding they held insufficient evidence to detain her. He escorted her out of the property’s wrought-iron front gate, a moment captured in a photo lying on the conference table. Wearing purple pumps and a long red coat over a pink dress, Puente carries a large maroon purse and pink umbrella, her eyes cast downward to watch her step. She trails Cabrera, his police badge clipped to the front of a dark blue jacket and his jeans tucked into knee-high black boots that he had donned for the day’s dig. His head cocked to the side, he looks back at her, preparing to usher her past the crowd that looms outside the frame.

He stares at the photo and points at her purse. “See how it’s bulging? It had about $2,500, $3,000 in it.” Cabrera shakes his head. “Didn’t know that at the time.”

The detective walked about halfway to the Clarion with Puente and her boarder, John McCauley. Once free of the throng, Cabrera stopped and watched the pair until they entered the hotel. He returned to the house, grabbed a shovel and began to dig. Twenty-one minutes later—he remembers the time precisely—he exhumed sufficient evidence: the remains of a second body buried about a foot deep in the earth. Officers rushed to the hotel to arrest Puente, but by then, she had bolted. Word reached Cabrera. “I had such a sick feeling,” he says. “I felt like someone had pulled my insides out.”

* * * * *

Puente watched the images flicker across the TV screen in her Los Angeles motel room. The Victorian on F Street. Cops hauling away body bags. The wanted bulletin for Dorothea Puente. A dark thought arrived.

“I wanted to kill myself.”

For a moment the prison’s visitors hall feels bereft of other people and sounds. I watch as she pushes away the empty plastic container of fried chicken strips and french fries that she finished eating earlier. Her statement hangs between us.

Some might interpret that as a kind of confession, I finally say.

She responds with a burst of words, scanning the room as she talks. “First off, I was getting the checks. I didn’t need to kill anyone. Why would I waste all my time to get these people cleaned up, make sure they have no diseases, get all their affairs in order if I was going to kill them?”

But there were seven dead bodies in your yard.

“The only time they were in good health was when they stayed at my home. I made them change their clothes every day, take a bath every day and eat three meals a day. These were people—the Salvation Army wouldn’t take them. When they came to me, they were so sick, they weren’t expected to live.”

A lot of people saw your running away as a sign of guilt.

“If I’m thinking about getting away, you think I’m going to ask permission?”

Police escort Puente after apprehending her in L.A.; Cabrera walks behind her. (AP Photo/Walt Zeboski)

Puente and McCauley had caught a cab from the Clarion Hotel to a West Sacramento bar. She settled her nerves not with coffee but a few vodkas with orange juice while he drank beer. The two then separated, with McCauley returning downtown and Puente taking another cab to Stockton, where she hopped a bus to Los Angeles. She holed up in the Royal Viking Motel for the next three days, seldom leaving her room. Back in Sacramento, police were digging up five more bodies, including Bert Montoya’s. Several were swaddled in bed sheets that matched linens found in the house.

Her escape brought coast-to-coast ridicule of Police Chief John Kearns and his department while authorities chased dead-end leads from Las Vegas to Mexico. As the search expanded, cabin fever seized Puente. On her fourth day as a fugitive, she dropped by a dive bar near the motel, introducing herself as Donna Johansson to a retired carpenter named Charles Willgues. The two talked through the afternoon, with Willgues both attracted to and wary of the well-dressed stranger who sipped screwdrivers. She came on a little hard, what with her questions about his Social Security benefits and abrupt suggestion that they consider living together.

“we never got along.”

They made a date to go shopping the next day, but Willgues returned to his apartment shadowed by an inkling that he somehow knew her face. He pieced the puzzle together a couple of hours after they parted, and later that night, police converged on room No. 31 of the Royal Viking. Puente surrendered quietly.

In another twist to the case, Sacramento police escorted her back to the city on a plane chartered by KCRA for its news crew. During a brief in-flight interview with reporter Mike Boyd, she said, “I have not killed anyone. The checks I cashed, yes.” In a cryptic aside, she added, “I used to be a very good person at one time.”

The public heard little from Puente for more than 20 years after that clip aired. Nonetheless, with decades to mull what she might say about her case, she sounds as unpersuasive now as during her plane ride from Los Angeles. Explaining away the corpses in her yard, she says, “Not one person who worked for me saw me doing anything wrong. People were always coming and going. Alcoholics don’t stay in one place for long. How did I know where they were?” Absolving herself, Puente fingers McCauley and another former tenant as the possible murder suspects. Both have died, and police cleared them early in the investigation. I ask why the cops targeted her. “I think they needed somebody and I was the easiest one around.”

Yet the most illuminating aspect of talking with Puente in prison arises from her silence about the dead. She does not once voice sadness over the deaths of her boarders, as if fearful that merely referring to them would imply her guilt. For someone who insists she worried over the well-being of her tenants, Puente tells me that, after her arrest, she fretted about Sam. “That was my tomcat. I didn’t know if anyone was going to look after him.”

Our visit winds down. Before leaving, I decide to return to the subject of Los Angeles, to the despair that descended as she watched the news in her motel room. I want to know what stopped her from killing herself.

“It’s the unpardonable sin.”

* * * * *

William Vicary spoke with Puente for the first time about two months after her arrest. The forensic psychiatrist, assigned to evaluate the alleged serial killer as her case proceeded toward trial, would spend 12 hours talking with her over the next four years. During their initial meeting, he encountered a woman of utter ordinariness, one far removed from the media caricature that depicted her as the embodiment of evil.

“I was struck by how pleasant and socially intact and intelligent she was,” says Vicary, who works in Los Angeles. “She did not strike me as a person who had a major mental illness. I was bewildered as to what in the world was going on with all these people in her yard.”

Prosecutors charged Puente with killing nine people. The total included a man she had met after her release from prison in 1985 whose body turned up the following year in a wood box next to the Sacramento River; Ruth Munroe, her former business partner; and the seven boarders found in her yard, among them Montoya, whom police speculated may have been unwittingly recruited by Puente to carry wrapped-up bodies out of the house, then perhaps learned the truth and paid with his life.

The case rested on the shifting sands of circumstantial evidence. Forensic testing had failed to determine a definitive cause of death in any of the victims. The seven tenants who had lived at 1426 F Street died with a variety of drugs in their bodies: anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, painkillers, tranquilizers. The lone drug present in all of them was Dalmane, a sedative for which Puente had obtained more than three dozen prescriptions of 30 pills each between October 1985 and November 1988, according to court records. She purchased the refills through a pair of doctors who, presumably oblivious to her past drugging of clients, trusted her stories that she simply wanted to help boarders sleep.

In theory, the blend of narcotics detected in the victims could have proven lethal, or weakened them to the point of defenselessness against suffocation with a pillow or blanket—a nearly untraceable cause of death. But the passage of months and years since the victims had died reduced the toxicology results to educated guesswork. Nor could anyone rule out that the four women and three men had taken the drugs on their own, considering their assorted substance addictions, physical maladies and mental illnesses.

Prosecutor John O’Mara, then as now head of the Sacramento District Attorney’s homicide unit, recognized the difficulty of cultivating compassion for victims he dubbed “the shadow people.” He had the added burden of building his case with witnesses of the same ilk: alcoholics, the homeless, once and future convicts. Beyond that lurked the vexing conundrum of the accused herself.

“Here’s this grandmotherly figure in this beautiful, restored Victorian house with all these azaleas and other flowers,” O’Mara says. He sits in his downtown office, shock of silver hair combed straight back from his high forehead, untucked short-sleeved shirt spilling over his jeans. “And then there’s the contradiction: beneath this house there are all these bodies. It doesn’t fit.”

Dorothea Puente. A dark thought arrived. “I wanted to kill myself.”

At least three people—defense attorneys Kevin Clymo and Peter Vlautin and their client—harbored scarce empathy for the prosecutor. Puente had already been convicted and executed in the media, and the attorneys understood the long odds of winning in court. “Common sense says that if you’ve got [seven] people who have died in your house, something’s gone wrong,” says Vlautin, who retired from the Sacramento Public Defender’s Office in 2005. (Clymo died in 2006.) “So we knew we’d have an uphill battle in convincing the jurors that all of those were accidental deaths.”

Procedural wrangling moved the trial to Monterey, after a judge ruled that the intense media coverage of Puente in the Sacramento region would preclude her from receiving a fair trial here. In November 1992, the same month jury selection started, she rejected a plea deal that would spare her the death penalty if she pleaded guilty to all nine murders. As the trial neared, Vicary found her in an agitated, paranoid state.

The psychiatrist diagnosed Puente as suffering from antisocial personality disorder, a condition marked by deceit and manipulation of others without remorse. He speculates that running a boardinghouse began for her as a humane endeavor rooted in a desire to undo painful childhood memories. “I think she truly wanted to rehabilitate [her tenants] as she could not the people in her own family,” Vicary says. “On the other hand, when these people, as could be expected, would act up—at that point, she snapped and decided to kill them.”

The Puente trial dragged on for five months, with more than 150 witnesses, thousands of pieces of evidence and unrelenting media scrutiny. She played the stoic in court, her face as frozen as her mug shot. “She sat there so totally motionless and emotionless,” says Honey Hewlett, one of 12 jurors seated for the trial, who stopped buying Giorgio perfume after learning Puente also wore the scent. “It’s like she was watching a movie she wasn’t particularly interested in.”

Jury deliberations commenced in July 1993 and soon stalled. Eleven jurors were convinced of Puente’s guilt in killing the seven boarders found in her yard; one juror disagreed. Tempers spiked as the impasse stretched to its third week. “Someone reached across the table at one point and almost got into a fistfight with him,” says Hewlett, who now lives in Oregon. For her and the others, one factor in particular undercut Puente’s claim of innocence. “I just don’t believe that strongly in coincidence. How many other boardinghouses have one person die? She had seven. That’s just too much coincidence.”

Finally, on the 24th day of deliberations, the holdout juror acquiesced, voting guilty on two counts of first-degree murder and one second-degree count. He neither explained his motive for capitulating nor discussed why he agreed to convict her of only three killings. As jury foreman Mike Esplin recalls, the man simply said, “That’s all I’m going to give.” Puente’s composure cracked after the last verdict was read. In his sessions with her, Vicary had inched up to the subject of guilt, knowing that she would withdraw if he asked directly whether she had killed people. “Her eyes would fill with tears, but she would never admit it,” he says. “It was too humiliating, too shameful for her to admit responsibility for these crimes. And it was so counter to her strenuous effort all her life to be somebody who was respected, somebody important.”

Puente received a prison term of life without parole after the jury deadlocked on whether to give her the death penalty, an ending that deepened William Clausen’s bitterness. Puente was acquitted in the poisoning death of his mother, Ruth Munroe, and Clausen, who testified at trial, regards the convicted killer’s every living day as a denigration of his mother’s memory. “She’s not hurting there in prison,” he says. “She’s got everything she needs, her life is taken care of. It’s sick.”

Clausen knows Puente’s appeals ran out last year. He also knows what will happen if by some unimaginable spasm of fate she should ever walk free. “I’ll be waiting for her.”

* * * * *

I stare at the brick and wrought-iron front gate through which Dorothea Puente walked for the last time on Nov. 12, 1988. It is late March and after midnight, the hour when she—possibly with the help of an unsuspecting Montoya or another accomplice, a mystery police never solved—buried bodies in the yard. The house at 1426 F Street, now painted a shade of gingerbread, appears occupied on the first floor and empty on the second, where she used to sleep. Most of the lot has been paved over. I wonder if the tenants know about the home’s notorious history. Or about the white-haired woman who turned the yard into a mass grave.

A few days later I drive to Chowchilla for my final visit with her. I pass through the check-in station, a process that requires visitors to pull pants pockets inside-out, remove their shoes and lift their stocking feet for inspection by guards. I stroll up the paved outdoor path that runs between the check-in station and the visitors hall, a walkway flanked with manicured rose bushes of the sort Puente once might have planted and pruned. Acres of almond trees and farmland border the prison, a vast archipelago of dun-colored, low-slung buildings moored inside electrified fences topped with razor coil. The silence here feels powerful enough to swallow space.

Puente has told me during previous meetings that her case still attracts worldwide attention, and that she recently spurned interview requests from a British newspaper and an Australian TV station. But she has shown too much interest in my visits for me to believe her. She has sent more than 15 letters and postcards in the months since I first wrote to her. Sometimes she includes small handmade gifts: Christmas ornaments constructed from cardboard and yarn, a greeting card stitched with fine thread. I now see them as tokens of loneliness, trifles to mark the time. Once, when I asked if she ever hears from her surviving siblings or two daughters, she shook her head. “As far as they’re concerned, I’m dead.”

I realize today will be our last conversation when Puente sits down at my table and makes a request. She wants me to buy dozens of food and beauty care items for her from a prison-approved vendor that will mail the goods to her. She will send me the list in a few days—the bill will total $114.70—but I already know I won’t oblige. In turn, I know that when she receives my letter telling her as much, she’ll cut off contact. I could give her my answer now, but there are a few more questions to ask.

I wonder if she ever wishes she had received the death penalty.

“Maybe I would have been better off. It’s the same thing. I’m here until I die.”

I wonder what she wants when death does come.

“That I can die peacefully in my sleep without being sick or being a cripple. I don’t want to be a burden on anyone.”

I wonder what it’s like to be known as a murderer.

She turns to look at me. We hold each other’s stare. I wait for her to speak.

“I don’t give a shit what anyone else thinks.”