Spirit Chaser

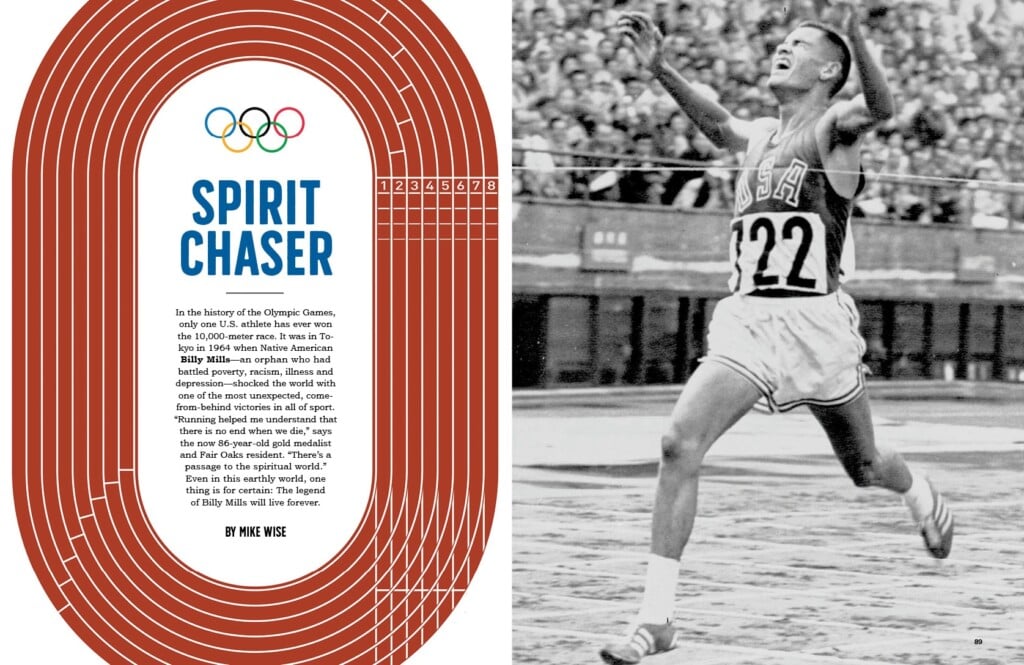

In the history of the Olympic Games, only one U.S. athlete has ever won the 10,000-meter race. It was in Tokyo in 1964 when Native American Billy Mills—an orphan who had battled poverty, racism, illness and depression—shocked the world with one of the most unexpected, come-from-behind victories in all of sport. “Running helped me understand that there is no end when we die,” says the now 86-year-old gold medalist and Fair Oaks resident. “There’s a passage to the spiritual world.” Even in this earthly world, one thing is for certain: The legend of Billy Mills will live forever.

With the evening light dying and the reflection of the pool shimmering through the Venetian blinds in his Fair Oaks home, Billy Mills leans in toward the laptop computer on his kitchen table. It’s late April 2024, and things are getting good in the last lap of the 10,000-meter race on the screen, which Mills—bespectacled and approaching his 86th birthday—watches with intent. It’s a last lap he knows well, a race he could tell you all about. It’s his own.

He looks on as if the drama on the track is unfolding in real time. Except the images on the screen took place long ago, on a rain-slickened cinder track more than 5,000 miles away in Tokyo, during the 1964 Olympic Games. And the 26-year-old Billy Mills was making his move. Raised in poverty on an Indian reservation, underestimated as an athlete since high school, withstanding alienation and racism even as a track star at the University of Kansas, Mills had disappeared from the camera lens on the final curve. And in keeping with the grit and surprise that defined his life to date, he was about to come from nowhere once again.

Suddenly, Mills fills the quiet home with the rat-a-tat-tat cadence of a sports announcer narrating the race six decades later. The adrenaline pulsates through both the present and past versions of the man, eliciting the kind of euphoria only a body hydroplaning at warp speed in those final 120 meters can produce. “I’m going to box Clarke in,” the elder Mills says of the man favored to win the race—Australian world record holder Ron Clarke. “So I move on his shoulder, start cutting in. Clarke accelerates, pushes me out. Gammoudi broke between us,” he says of the Tunisian runner Mohammed Gammoudi, who forcefully pushes his way through Mills and Clarke to take a commanding lead with only a minute or so left in the race. It was a lead Gammoudi would hold until only seconds before the finish. “I’ve got to do it now!” Mills says.

But the 2024 Mills already knows how the race will end—with his younger self bursting past Gammoudi, breaking the tape in front of 70,000 cheering spectators, raising his arms in victory, and making Olympic history.

Unsung, unranked, unaware that Oglala Lakota orphans aren’t supposed to overcome generational trauma and poverty to become Olympians—hell, struggling to even wrangle proper running shoes mere days before the race—Mills stunned the world in record time, nearly 50 seconds faster than he’d ever run that distance. To this day, he remains the only American to ever win gold in a 10,000-meter race at the Olympics.

Billy Mills at his home in Fair Oaks, backed by sacred eagle feather headdresses gifted to him from numerous tribes over the years. (Photo by Max Whittaker)

While for many, the memory has diffused with time, Mills’ achievement remains no less monumental to those who witnessed it years ago. “The significance is that he won, that he was an American winning a race that Americans don’t run [at the Olympics], that he came from his Native American background and that he achieved it with an almost spiritual effort of self-belief,” says Amby Burfoot, for nearly two decades the editor-in-chief of Runner’s World magazine and the winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon. “And I’m not a woo-woo guy. I’m not someone who goes around saying, ‘If you think it, you can achieve it,’ and crap like that. But Billy did somehow have enough faith in himself to set an extraordinary goal and then made it happen.”

From Paris, the site of the Summer Olympics that start on July 26, to Mills’ beloved Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, his surreal victory has inspired athletes and nonathletes alike. Nicholas Sparks, the best-selling novelist (The Notebook, Message in a Bottle, A Walk to Remember) who became a close friend of the Mills family while growing up in Fair Oaks, remembers catching a glimpse of his idol when Sparks was only about 12 years old. “I was kind of one of those kids who grew up with great-athlete, hero worship,” Sparks says today by phone from his home in North Carolina. “And there he was. I’d see him walking through the supermarket, and it’d be, ‘Oh my God, that’s Bill Mills. He won the Olympic gold medal.’ ”

It’s still regarded as one of the greatest Olympic upsets ever, simply because of Mills’ near-total anonymity before and after he arrived in Tokyo. (During the race, one of the broadcast announcers encapsulated that sentiment: “Billy Mills of the United States is in there—a man no one expects to win this particular event.”) All Mills had to do was overcome history—and not just the fact that an American had never won the Olympic 10,000 meters. No, it was much deeper and more layered than that. He had to overcome a century of his people’s pain.

![]()

In 1877, a malnourished 5-year-old Lakota boy traveling with his widowed mother, three brothers and sister approached men in midnight-blue uniforms seated at a large wooden table on the outskirts of what is now called Fort Robinson, Nebraska. They were surrendering.

Not long before, that widow—Sallie Bush Mills, the great grandmother of Billy Mills—had pleaded with the great Oglala Sioux warrior Crazy Horse, whose face today marks the world’s largest mountain carving, in South Dakota, to travel with his followers and live among the last free-roaming band of Lakota people. He agreed to take the woman and her children in. But as one of the fiercest and most fabled defenders of Native American territory, he and his followers eventually surrendered to U.S. troops at Camp Robinson, where he was killed only months later.

The 5-year-old boy was Benjamin Mills, Billy’s grandfather. Only in recent decades, through Sandy Swallow, Billy’s first cousin who’s worked diligently on the family’s genealogy, did Billy learn of his direct link to Crazy Horse’s band from copies of the U.S. Army’s official surrender ledger.

Eleven miles northeast of where Mills was born and grew up, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, was the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre, where in 1890 the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry used rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns to slaughter an estimated 300 Lakota men, women and children before dumping their bodies in a mass grave. The last major armed conflict between the U.S. government and the American Indians, it was originally called “The Battle of Wounded Knee,” and the 20 Medals of Honor given to soldiers who participated in the slaughter are still recognized by the U.S. Congress. It also holds a dark distinction: More than a century later, Wounded Knee, of all cruel ironies, is still the deadliest mass shooting in the nation’s history.

Grandpa Ben, that 5-year-old in 1877, never said a word about the past. No one on the Pine Ridge Reservation did. The nuns at the boarding school and society at large wanted them to move on and assimilate. “That was the way of life. It was just the fact of the matter, to survive,” says Mills’ 88-year-old brother Walt from his home in Peoria, Arizona. Hewing to the Indian Boarding School’s warped mantra—“Kill the Indian, save the man”—they had to cut their hair, speak proper English and forget their tribal traditions. No Lakota words. Ever. “None of us kids spoke Lakota,” Walt adds. “It was discouraged, even by your parents.”

The third to last of Sidney and Grace Allman Mills’ 12 children, Billy lost his mother to cancer when he was 8. The defining moment of his childhood, he says, happened several months later when his father took him fishing for bullhead catfish in a creek fed by the reservation’s White Clay reservoir. The sun rose over the yellowed wavy hills of scattered oak and sycamore that summer when Sidney Mills picked up a thin, dried, broken tree limb, roughly three-feet long, still covered in moss. Drawing a crude circle in the moist earth around his son, he instructed the boy to stand in the middle of the circle and close his eyes.

Mills, seen here as a boy on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, grew up as part of the Oglala Lakota tribe. Orphaned at 12, he was raised by his older sisters. (Photo courtesy of the Mills family)

“Son, you have broken wings,” he told Billy, who recounts his father’s words from 1947 in vivid detail today. “You’re feeling pain. Do you feel hurt? Look beyond the hurt, the hate, the self-pity, the jealousy. You’ve got to look deeper, way down deep, where your dreams lie. It takes a dream to heal a broken soul. You have to find a passion, and from that comes the potential to have the wings of an eagle.”

Over the next three years, his father suffered several massive strokes, and Mills became an orphan at 12. He slept in the same bed with Walt in a small clapboard tenement, built beside a dirt road, that housed his other siblings. They had no electricity, no running water (save for a single water pump) and no indoor plumbing. The bathroom was an outhouse adjacent to their home. He was raised by two of his sisters, 18-year-old Margie and 16-year-old Ramona. No one in the household knew the term “generational poverty.” They only knew bologna sandwiches tasted heavenly and they had enough to eat and live on, largely unaware of the hand most Native American children had been dealt.

Pursuing an athletic instinct, Mills tried boxing, his father’s chosen sport, for a while. But after his skull was thumped repeatedly by bigger boys on the reservation, he “retired” at 0-6. He was 5-foot-2 and 104 pounds when he left home and entered his freshman year of high school at the prestigious Haskell Institute, serving Native American youths in Lawrence, Kansas. He tried out for every sport at Haskell and found he was decent at exactly one: running. He didn’t make the track team as a freshman, but he quickly found that the benefits of the sport transcended intramural competition.

“Running was spiritual to me,” Mills says. “Running helped me understand that there is no end when we die, there is a transfer, there’s a passage to the spiritual world. My dad would say we come from Mother Earth. And when we die, we go to Mother Earth. Dust to dust. But spiritually, we live on forever.” He took further inspiration from an article his father read to him before he died about “Olympians being chosen by the gods.” Young Billy’s adolescent reasoning went like this: “If I became an Olympian, and I was chosen by the gods, maybe I could see my mom again.”

By his sophomore year at Haskell, everything changed for the budding track star. He won just the third cross country race he ran that season. For the rest of high school, as he grew to 5-foot-10 and his gangly arms and corn-silk thin legs now became the pistons of a churning machine, Mills posted nationally ranked times and never lost a cross country race again. The University of Kansas, with its premier track and field program that developed two-time indoor mile world-record setter Wes Santee, offered him a full-ride athletic scholarship.

Away from classmates and families who looked like him for the first time, he would hear racial slurs at meets and face such indignities as a fellow student at a KU party shoving a set of bongos in his face, saying, “Hey, we’ve got an Indian guy here. You play these!” But what Mills recalled most about being a Jayhawk was the overwhelming acceptance his running exploits afforded him. He wasn’t just the “Injun kid” anymore. He was an All-American distance runner. He had carved out a post-Pine Ridge identity for himself. No one or nothing could take that away.

Until his junior year. Nov. 24, 1960, to be precise—the day Mills claims as the demarcation line in his life and career.

That morning, at the Amateur Athletic Union championships in Louisville, Kentucky, he had completed the 10,000-meter race in a personal best of 31 minutes and 58 seconds. Just four competitors finished ahead of him in a field of over 100 of the world’s top amateur runners. Moments later, Mills was standing with a handful of fellow athletes when a photographer asked them to line up for a photo. If athletics had indeed emerged as America’s great desegregation tool, Mills thought, then it was at this time, on that track, that he belonged. But then the middle-aged white photographer stopped looking through his lens and fixed his gaze directly on Mills.

“Can that one step out? The darker-skinned one, can you step out?” he blurted. Mills looked blankly at him for several seconds, frozen by the man’s words. The photographer repeated, more forcefully, “Please, get out.”

Mills walked away dejectedly. “The racism broke me,” he recalls. When he returned to his fourth-floor hotel room in Louisville, he looked down at the asphalt below his window and decided, right then, he would jump. He pulled the hotel chair away from the desk, pushed it against the metal pane and opened the glass. He looked out once more from his window, now feeling the crisp cold of the afternoon air. “I just wanted to go where it would be quiet,” he remembers. In that moment, he could make the pain go away.

He climbed atop the chair, his right hand on the glass, his torso now inches over the railing as he slowly leaned forward. Just one step and it would all be mercifully over.

“Don’t!” A jarring physical sensation he had never known, an incessant tingling, came over his entire body. He tilted his head away from the window and looked toward his room. “Don’t!”

His father had been dead for more than 10 years, but he knew that voice—his baritone cadence echoing from the spirit world, urging his son not to take his own life. It had to be.

Mills stepped down from the chair and pushed it back behind the desk. He breathed heavily for at least a minute before picking up a pencil and opening a journal he often carried with him. Moments later, he had inscribed a purpose: “Gold medal. 10,000-meter run. Believe. Believe. Believe,” the note read.

![]()

Mills would learn almost a year later how a perfect mental and physical storm had brought him to that window ledge. He was diagnosed with hypoglycemia, which can bring on an undetected form of depression when his blood sugar is low. Paired with the soul-siphoning rejection he felt after the meet, his condition turbo-charged his suicidal ideation. “I came sooo close,” he says. “I just wanted to go where it was quiet. I just didn’t want to deal with that anymore.” And then the voice. “Energy. Movement. ‘Don’t.’ That was my dad’s voice. I felt it.”

Mills, pictured around 1955, found his footing as a high school track star at the Haskell Institute in Kansas. “Running was spiritual to me,” he says. (Photo courtesy of the Mills family)

Within a month, during winter break, Mills called the campus switchboard hoping to find a fellow KU undergrad to go out with him. Rifling through dorm rooms whose landlines went unanswered because most coeds had left for Christmas, the switchboard operator finally said, “You’re really having a tough time tonight, aren’t ya?”

“Well,” he replied, “how about you?” And he asked her out.

After her shift ended, Patricia Harris, a junior art student from Coffeyville, Kansas, met the man on the other end of the phone for a blind date. A little over a year later, as KU seniors in January 1962, they were married. When Billy needed an extra semester to graduate, Pat quit school and began working to support both of them. Her own dreams of becoming an artist were put on hold. Every sacrifice became about furthering her husband’s running career. He had let her in on the dream. “That’s when it became, ‘We,’ ” Billy says today.

Knowing he would have to register for the military draft in 1962, he applied and was accepted to the Marine Corps’ officer candidate school after graduation from Kansas, where he’d helped the Jayhawks to win two national track and field titles.

Before shoe companies sponsored runners and the birth of elite professional running clubs, the best of the best were recruited by military teams to run against other branches of the service. But the competition wasn’t elite enough to make anyone in the little world of track and field a believer.

After qualifying for the U.S. Olympic Trials in the 10,000 meters, he traveled to Los Angeles in September 1964 to compete. (The “summer” Olympics in Tokyo took place in October to avoid the humidity and typhoon season of earlier months.) He had still never won a major race. His odds of being among the top three trials finishers—thus qualifying for the Olympics in Tokyo—were not great: Gerry Lindgren, 19-year-old phenom from Spokane, was the favorite in Los Angeles. But Mills surprised everyone with a stunning second-place finish—10 seconds in front of Ron Larrieu, the final qualifier.

Prior to the trials, when another athlete’s wife asked Pat if she was going to Tokyo, she said she didn’t know. Billy hadn’t even qualified yet. However, he had a bold hunch: Gambling on himself, he took out a loan from a local bank near Camp Pendleton, his Marine Corps base just north of San Diego, to purchase air and hotel tickets for his young bride. When he then tried to return the money in a moment of self-doubt, Pat wouldn’t have it. “I didn’t know going to the Games was so important to you,” he said to her.

“It’s not,” she replied. “I just know you want to win. And I know you cannot win if I’m not there.”

A little over a month later, on Oct. 14, Pat was sitting in Japan National Stadium in Tokyo. She was armed with an 8mm camera to film the 10,000-meter race. She watched her husband step onto the track with 37 other runners—still among the largest contingents in the history of the 10,000-meter Olympic final. Minutes before the start of the race, Mills realized he hadn’t eaten enough to ensure his hypoglycemia didn’t interfere with his race. He found a track official in the locker room, who retrieved a Japanese candy bar made of chocolate, nuts and caramel.

Among the crowded field, he lined up on the outside of the track in his No. 722 singlet. Clarke, the heavily favored Australian, was up front with Mills’ American counterparts, Lindgren and Larrieu.

The gun sounded. Czechoslovakia’s Josef Tomas sprinted toward the front. The Soviet squad, including defending Olympic champion Pyotr Bolotnikov, soon moved ahead, closely followed by the Americans. But Lindgren, the U.S.’s best chance coming in, had suffered a sprained ankle while training in Tokyo, and he and Larrieu quickly dropped out of contention. By the halfway point of the 25-lap race, a pack of five runners were contending and, improbably, Mills was in the lead. He held on still with just two laps remaining, battling with Clarke, the upset-minded Mohammed Gammoudi and Ethiopia’s Malmo Wolde.

Then Wolde fell back, and it was down to three.

Clarke led at the beginning of the final lap when Mills made his move. Even now, watching the video, it’s extraordinary to see the contact as Clarke refused to let Mills take the inside lane, pushing his right forearm and shoulder into the American’s torso until Mills veered off course into the next lane. Then Gammoudi slipped through both men, picking up his stride, as he made his run for gold. Mills was nowhere to be seen on the last curve, with less than 150 meters left. Gammoudi was ahead of Clarke by at least five meters and Mills by at least 10 meters.

And then it happened.

As Clarke and Gammoudi navigated in and around lapped competitors with less than 100 meters to go, Mills bolted to the outside, taking an empty Lane 4, and began raising his knees and flailing his arms forward in an all-out sprint.

“ ‘Wings of an eagle,’ I thought, as I started sprinting,” he recalls. “ ‘Wings of an eagle.’ My father’s words had come back to me.”

Mills (No. 722) in his historic race in the 1964 Tokyo olympics, keeping pace with heavy favorite Ron Clarke (pictured right of Mills wearing No. 12). Mills withstood hard contact from Clarke in the last lap of the race, ultimately sprinting past the Australian in the final stretch to cross the finish line first and notch a new olympic record for the 10,000 meters. (Photo by Takeo Tanuma/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Clarke was about to catch Gammoudi when he saw Mills fly by him. His spirit defeated in that millisecond, the world-record holder inexplicably slowed his stride. Mills, still in a dead sprint, catapulted past Gammoudi. As NBC’s Bud Palmer called the final sprint, his broadcast booth sidekick Dick Bank—who moonlighted as an Adidas shoe rep at the Olympics and days before had helped Mills procure his first-ever pair of new spikes for the race—screamed an iconic call into his microphone: “Look at Mills! Look at Mills!”

He won in 28 minutes, 24.4 seconds, setting a new Olympic record. Gammoudi held on for second in 28:24.8, with Clarke third in 28:25.8. Japanese Emperor Hirohito stood and joined the crowd in applauding wildly at National Stadium. Grown men were moved to tears. Cordner Nelson, the Track & Field News correspondent covering the race in Tokyo, wrote that day: “A hundred and fifty pounds of fighting man went into action with an all-out sprint which abruptly turned sane men into screaming hysterics. With each stride of his 5’-11” frame the Marine Lieutenant bore down on his rivals. […] With a wild grin, Billy Mills hit the tape, arms raised in a leap of sheer joy.”

Amid the euphoria in the stands, the batteries on Pat’s 8mm camera had run out as her husband flew by her in the final stretch. “The next thing I saw were his hands going up in the air!” she recalls. “Everyone was going crazy! A Japanese official found me and said, ‘The new Olympic champion wants his wife!’ ”

Gold medal in tow, the couple returned home to Camp Pendleton. “We came in the back gate all by ourselves late at night,” Pat says. She still remembers a sign newly posted at the base, reading:

Home of Billy Mills

Olympic Gold Medalist

Within weeks, thousands at Memorial Stadium in Lawrence, Kansas, unleashed a throaty roar when Mills was introduced during the Nebraska-KU football game. Coffeyville, Pat’s hometown, made him its adopted son, feting him with a ticker-tape parade and banquet. Pine Ridge, the reservation that raised him, bestowed the greatest honor: He was made a warrior by tribal elders in a naming ceremony, replete with an eagle-feather headdress. Tamakoce Te’hila, they named him—Lakota for “Loves His Country.”

His accomplishment and influence inspired runners around the country. “I had heard the news that Billy Mills had won the 10,000 meters,” says Burfoot, the longtime Runner’s World editor, thinking back to when he was a freshman at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. “And of course I knew that was impossible because I was actually following the sport closely. I was at a cross country practice, and I just kept explaining to these guys the significance of this victory. And I kept saying to them, ‘Listen, if Billy Mills can win the goddamn Olympics, I can win the Boston Marathon. Who knows what the boundaries are? There are no boundaries. Now we can go for it because he has shown us the way.’ ”

Billy Mills holds the shoes he wore when he won the gold medal in the 10,000-meter race at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. (Photo by Max Whittaker)

Meanwhile, the young Millses had the rest of their lives to live, adapting to the long, bright afterglow of Billy’s triumph. “We were so naive,” Pat recalls today. “We were so young at the Olympics. We had no idea what was going on. We just showed up, and Bill won. And then we came home. We came in, unpacked our suitcases.” In 1964, elite Olympic athletes had neither agents nor public relations gurus on retainer. Mills knew the Marines wanted to use him as a spokesman, and his commanding officer at Camp Pendleton insisted he be honorably discharged after doing PR instead of possibly going to Vietnam with his unit.

Mills competed for a while after Tokyo, a stretch that included setting a new U.S. record for the 10,000 meter, and a new world record in the six-mile that he shared with former Olympic teammate Gerry Lindgren—both feats accomplished in 1965. Once he didn’t qualify for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, however, he decided to move on from competitive racing.

But after the military, everything felt overwhelming. What would they do for post-career employment? Could they afford to add to their young family, which already included their 3-year-old daughter? “We had no idea what we were doing,” Pat says.

They had another six decades of marriage ahead of them—including a half-century in Fair Oaks—to figure it out.

![]()

Billy and Pat moved to Fair Oaks in 1973, relocating from New Mexico in part to join family friends and his sister Thelma, who all lived in the area. (Thelma turned 87 in March; three of Billy’s 11 siblings are still alive.) Mills tried to stay in shape by running on the American River Parkway trail. In 1988, with a growing family, they bought some land and built a larger, two-story home nearby. There, Mills keeps the sacred eagle feather headdresses gifted him from various tribes and mementoes from his running career—including the gold medal—behind glass. Pat’s abstract expressionist paintings share the space, emblems of her own accomplished artistic career. (Her work also hangs in the World Olympic Museum in Lausanne and the USA Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs, and has appeared in galleries from Reno to Alberta, Canada.)

Mills sold health and life insurance for much of the decade after he and Pat arrived in the Sacramento region. It paid the bills, but in the end, nothing beat being Billy Mills—Olympic gold medalist and symbol of cultural resilience and success. He first dabbled in motivational speaking as an emissary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which deployed him to reservations as a positive presence with a message of self-determination that mirrored the organization’s goal at the time. He sought to inspire kids who, like him, had nothing growing up to believe in themselves.

At a certain point, he figured he had told his story enough. Pat thought there was more, though, and that her husband’s calming voice and conviction, along with the story of his life, could inspire anyone. Pat tried to book him to speak to insurance agencies, but she ran into a problem: No one took the wife of Billy Mills seriously enough as a public relations person. So she got an idea: Don’t tell anyone she was his wife, and make up her own speakers bureau. Thus, the Anne Harris Agency was created. People liked Anne Harris (Pat used her middle name and maiden name). They trusted her, and thus began Billy’s long speaking career around the country.

Mills receives the Presidential Citizens medal from President Barack Obama at the White House in 2013. The Olympic champion was recognized in part for co-founding the charity Running Strong for American Indian Youth. (Photo by Jacquelyn Martin/AP Photo)

And their first secretary? Nicholas Sparks. In their office, Pat has an original manuscript of The Notebook, Sparks’ first blockbuster novel, which he gifted to them. Sparks dated one of their daughters for three years at Bella Vista High School, where he ran the 800-meter and the mile well enough to earn a track scholarship to Notre Dame. (He still holds the Bella Vista 800-meter record and is part of Notre Dame’s nearly 40-year-old record in the 4×800.) They broke up midway through Sparks’ freshman year in college, but his close connection to the Mills family only strengthened. When Sparks was married a few years later, Billy and Pat even paid for his honeymoon. They are godparents to each other’s children and grandchildren. Sparks’ daughter Lexie, who graduated from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in May, was inspired by Mills to join Teach for America, which places the nation’s top college graduates as educators in underserved communities. She’ll serve her two-year term at an elementary school on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

“All my kids grew up calling them Grandma Pat and Grandpa Bill,” Sparks says. “And whenever we visited Sacramento, I had money, but theirs was the only house we would ever stay in. Pat and Bill would put me and my wife up with our five kids and our nannies.” For Sparks, who lost both his parents in his 20s, the Millses became relationship role models. They complimented each other and embodied the laughter, respect and pride in their children he sought.

The speaking engagements and renewed interest in Mills’ incredible Olympics feat resulted in the 1983 silver screen biopic Running Brave, starring former teen idol Robby Benson as Mills. And three years later, he co-founded a non-profit charity called Running Strong for American Indian Youth, which provides Native youth on the Pine Ridge Reservation and beyond with resources from water wells and grow-your-own farms for families to winter coats, school supplies, after-school programs and college scholarships. Today, Running Strong is managed by Billy’s niece, Sydney Mills Farhang, named for her grandfather and Billy’s father.

In early May of this year, Mills returned to Kansas and his former high school campus—now Haskell Indian Nations University—to deliver the commencement speech. He has even adapted his story to an acclaimed children’s book in time for the 60th anniversary of his golden race: Wings of an Eagle, co-written with Donna Janell Bowman and published by Little, Brown and Company, will be released July 2 and featured as one of 2024’s Great Reads at the Library of Congress’ National Book Festival this summer in Washington, D.C.

Over the decades, the boy from Pine Ridge and the girl from Coffeyville, Kansas, estimate they have been to 100 countries. Going to the Paris Olympics in July will be Billy’s 14th Olympics trip, including Tokyo and three Winter Games. Billy and Pat will lead a family delegation to Paris, including the pair’s daughters and their families. There is a feeling this could be the couple’s last Olympics.

Billy and Pat Mills stand outside their home in Fair Oaks on April 29. In July, they will lead a family delegation to travel to the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris. (Photo by Max Whittaker)

Back in his Fair Oaks home, Mills considers the future. He says he wants his ashes to be spread at the base of the Crazy Horse Memorial, in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota.

Not so fast, Pat says good-naturedly. Ever the adopted Sacramentan, she’d like some of his ashes spread with hers someday at Fair Oaks Cemetery.

“Sure,” he says with a wry smile. “You can have some.”

![]()

It’s dark now, almost 9 p.m. The video of the race ends like it always does, with Mills grinning from Tokyo to Pine Ridge. The laptop is put away.

It’s not until some 10 days later, that Sparks mentions a peculiar detail from that October day in 1964, prompting closer examination.

“I remember a moment when my mom died when I was 23,” he says. “I went and sat and talked with Bill, knowing he’d lost his parents when he was younger. [I wanted to know], ‘How do you get through it?’ He told me a great story about his dad’s presence at times, including in the final lap in the Olympics.”

Asked about it, Mills knows what Sparks is referring to: He was in Lane 4, coming wide off the curve, fighting to keep pace with Clarke and Gammoudi. Germany’s Siegfried Herrmann, realizing the eventual medalists were about to lap him, made way for all of them in Lane 5. As he passed the German, Mills caught an image on the front of Herrmann’s running singlet.

“And in the center of his jersey is an eagle,” Mills recalls. “And I’m back to being this little boy on the reservation when my dad says, ‘Son… one day you can have wings of an eagle.’ Wings of an eagle. I can win!’ ”

After the victory, Mills found Herrmann to tell him the eagle on his singlet helped him win. But it was then that he realized there was no eagle—it was just the five Olympic rings. “It was basically a perception,” he says. “And perceptions can create or destroy us.”

In the case of Billy Mills, it could have done either. But he made that choice to change his own perception a long time ago, moments after stepping off that window ledge. He made the choice to believe, believe, believe.

View More: Footage and Commentary from Mills’ Historic Race

You Might Also Like

Rock Star – Legendary rock climber Beth Rodden

A Mighty Heart – WNBA star and olympian Mighty Ruthie Bolton