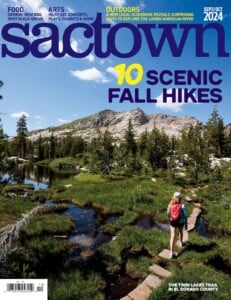

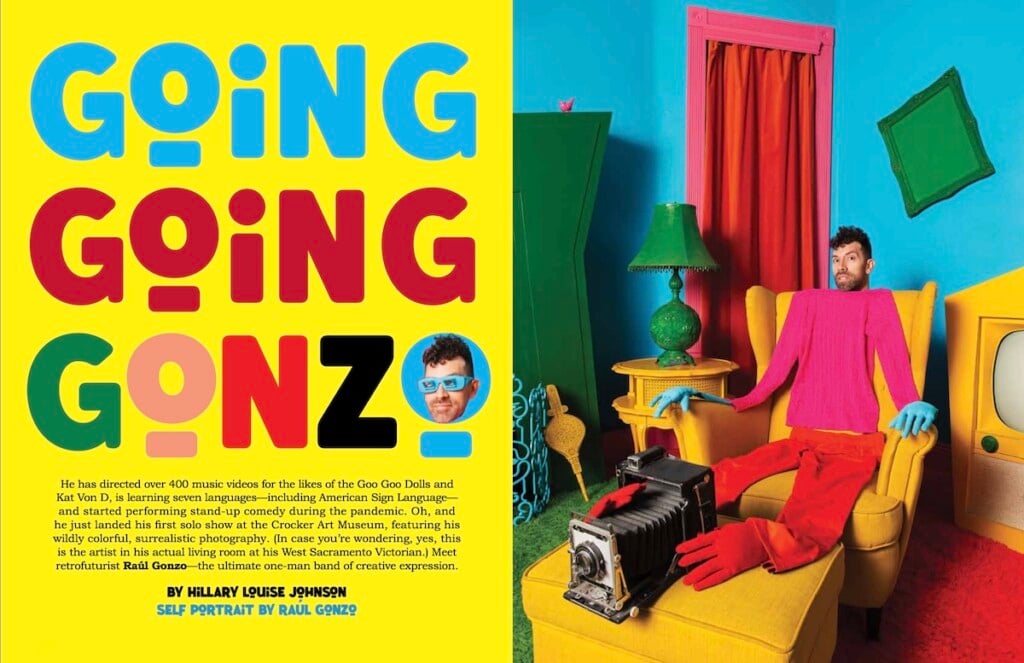

Going Going Gonzo

He has directed over 400 music videos for the likes of the Goo Goo Dolls and Kat Von D, is learning seven languages—including American Sign Language—and started performing stand-up comedy during the pandemic. Oh, and he just landed his first solo show at the Crocker Art Museum, featuring his wildly colorful, surrealistic photography. (In case you’re wondering, yes, that is the artist in his actual living room at his West Sacramento Victorian.) Meet retrofuturist Raúl Gonzo—the ultimate one-man band of creative expression.

Raúl Gonzo looks out of place in his own living room. That is because, sitting there in his faded jeans and concert tee, holding a cup of coffee, his human form practically disappears against the super-saturated visual thrum of this parlor painted in shades of fuchsia, marigold, cyan and shamrock green.

But the mismatch isn’t just about color: It feels like the living room should be inside Gonzo’s head, instead of outside. In the hallway behind him, a table and chairs melt into the wall, as does a lamp and half a rotary dial telephone, while a bespectacled stag’s head smokes a pipe over a fireplace mantel that veers at a dizzying cant, on top of which a neon yellow blunderbuss waits for Elmer Fudd to come over for some Wabbit hunting with Hunter S. Thompson. It’s like the dream sequence from Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound interpreted as a Looney Tune directed by Tim Burton—all influences on his work, according to Gonzo.

This vivid dreamworld instead lives inside a weathered Victorian-era duplex in West Sacramento’s Washington neighborhood, just across the river from the Crocker Art Museum, where Gonzo’s first solo museum show, Color Madness, opens June 30, with about two dozen of his elaborately staged photographs. The display features two pictures that were taken in this very room, including A Woman’s Den, in which a brunette model wearing 1950s lingerie and thigh-high velvet boots cradles the comical yellow gun in front of the tilty green fireplace, a dangerous, glamorous vamp plunked down smack in the middle of Toontown, unaware that the more seriously she takes herself the more hopelessly absurd she appears. Ah, isn’t that the human predicament?

It feels significant that Gonzo inhabits this stage set, which blurs the lines between conscious and dream states, fiction and reality, 24/7. He’s a bit like Vincent van Gogh eating his pigments in a gut-level attempt at merging with them, except Gonzo is bathing in them instead.

Lanky, languid and affable, Gonzo is the spitting image of a young Jimmy Stewart playing opposite an invisible, 6-foot, 3-inch rabbit in Harvey as he describes the process through which he stages elaborate sets for his distinctive photographs. Then he stops, grins and says, “If this work was a relationship, it would probably sound kind of toxic.” He shakes off the notion. “No, no, no! I’m obsessed with it, and it’s obsessed with me. I’m sure it’s healthy.”

![]()

Gonzo started life as a Raúl, but with a different last name that he politely declines to share. He left it behind when he was christened “Gonzo” at age 20—not by his parents, and not by himself, but by his fellow art students at Yuba College in a bit of art-school cleverness. They were riffing off of two characters in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, author Hunter S. Thompson’s fictional alter ego Raoul Duke and his sidekick Dr. Gonzo.

Namesakes aside, a better candidate for spirit guide might be Gonzo the Great, the quixotic Muppet prankster of uncertain species who gleefully ate a rubber tire on stage to the tune of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee” on The Muppet Show in 1976—a puppet striving to create performance art, or to parody performance art, or both. “I feel like I’m more like that Gonzo,” Raúl agrees, “who is called that just because he’s weird.”

Francesca Wilmott, the Crocker’s curator of art who is staging the show, calls him a retrofuturist—and he thinks she’s nailed it. “That is one of my favorite words to say: retrofuturistic. It’s nostalgic. It sometimes feels romantic, or provocative,” he says, before dropping into a mischievous, conspiratorial whisper, to add: “But most of the time, it has to be funny. If it’s not funny, I’m not super interested.”

His images usually feature pinup-perfect, vaguely mid-century female figures, often captured in awkward stances or situations that are each a little tragicomic: tripping over a shopping cart in a market with no labels, driving while crying, watching an exploding TV set. They are all dreamily beautiful, and something about their brightly colored lives is always off. Retrofuturistically speaking, they’re reminiscent of a meme from a couple of years ago that George Jetson, everybody’s favorite ’60s dad from the future, was supposed to have been born in 2022. The anachronistic women in Gonzo’s images seem to be grappling with the realization that, to quote the little “g” gonzo philosopher Yogi Berra, the future ain’t what it used to be. And it’s hard to know whether to shout at them to wake up and smell the climate change, or give in and join them in their gorgeous, melancholy defeat.

In addition to the staged images, the Crocker show includes an immersive, experiential installation that puts museum visitors aboard a fanciful, fictional version of a pink-soaked Pan Am airliner. Museumgoers can sit in the seats for a one-way flight to Gonzoland, watching a video loop called Color Madness in Motion, composed of live-action video from Gonzo’s photo shoots, so that the images in the exhibit flutter to life.

Gonzo got a taste for the interactive installation piece when he participated in the Art Hotel project in 2016, when roughly 100 artists were invited to create work inside the rooms and hallways of a downtown Sacramento hotel slated for demolition. He placed a red bathtub in a red room and filled it with clouds and rain (a photograph of that design, Tea Time, Bath Time, Part I, with a model in the tub holding a blue umbrella, is included in the Crocker exhibit). In the casual atmosphere of the Art Hotel, Gonzo was delighted to see visitors jumping into the bathtub to take selfies.

“He’s created his own dreamworld, and we’re hoping with the exhibition and with that immersive set that you’ll be able to actually step into that world,” Wilmott says. “You are transported—that’s the goal.”

Nine years ago, Gonzo stumbled upon the technique that would come to define this and perhaps the rest of his life’s work when he directed a video in 2015 for Texas-based singer-songwriter Victoria Celestine called “Wasted Tears,” in which his concept was to have the singer lying on a bed in a room where everything on the set is white. “That was so fun,” he says. “Then I thought, ‘Wait a minute, I can paint things.’ ” Not just white, but any color. He had been looking for a way to respond to what he saw as an unwelcome shift in video and still photography toward CGI-generated inauthenticity. Where he’d loved the stop-motion and other tangible, real-life visual effects in early Tim Burton films like Pee Wee’s Big Adventure and Beetlejuice, Gonzo found the digital manipulations of Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory adaptation soulless. So almost as a cry of protest, he started creating his own real-life effects using paint. He painted things that by rights should not be painted, like a car—windows and all—a telephone, a TV set with no screen. To Gonzo, it felt transgressive. “No one’s going to knock on my door and be like, ‘Excuse me, sir, you can’t paint that,’ ” he says. “But it really felt like I found a loophole in the system.” He’s onto something: The perfect, digitally mastered images we see around us everywhere leave nowhere for our imaginations to flourish, while Gonzo’s stagecraft leads us dreamily by the hand into the potent land of make-believe.

This was the start of Gonzo’s Color Madness series and his journey into fine art photography. “I was only going to do a couple, but then I fell in love,” he says.

This aha moment led to a focused body of work where “real” objects and people are colored as brightly as if they were animated, and some stunning effects are achieved using the simplest mechanical means. Consider one shoot where a model named Mosh (more on her later) appears in the middle of a bright yellow spotlight surrounded by darkness. Gonzo shared a post on Instagram showing how the effect came about: In the image, there appears to be a spotlight. In a short video panning around the meticulously created set, however, you can see that the circle of yellow light is painted across the objects, as is the black background.

Surprisingly, Color Madness will be the first fine-art show of any kind for the 45-year-old artist from Yuba City, who is already a successful music video director—he’s made around 400 of them for clients as notable as the Goo Goo Dolls, Kat Von D, Grammy-winning British artist Jacob Collier and, locally, Deftones’ lead singer Chino Moreno. One music video he directed for a collaboration between MAX and Chromeo in 2019 has racked up nearly 7 million views on YouTube. Another for the Japanese band One Ok Rock has clocked over 21 million.

“I haven’t even had anything in a gallery yet, so I’m doing things backwards,” he says. “I’m pretty naive about how it works. I just appreciate being able to show while I’m alive. I know that sounds funny, but I’m serious.”

![]()

Gonzo was born in Artesia, near Anaheim—fourth-generation Mexican American on his father’s side, a “Caucasian mix” on his mother’s side. His parents divorced when he was just 3, and he grew up with a single dad, a carpenter who moved them around a lot, eventually settling in Wheatland when Gonzo was 13. As soon as he turned 17, he lit out for the big city—Yuba City, that is.

He took some art and videography classes at Yuba College—that was where fellow students took to calling him Gonzo—and bought a 35mm Pentax film camera to start shooting this and that, very much under the influence of Tim Burton and Wes Anderson, he says now. By 24, Gonzo had a job teaching film at the Marysville Charter Academy for the Arts, and was divorced with two children.

His world got bigger at age 27, when he found a mentor in Dean Tokuno, a fashion photographer with clients like Marshall Field’s and Filene’s who had semi-retired to take over his family’s Yuba County walnut farm. Tokuno had also shot advertising photography for David Lynch’s surreal and groundbreaking TV masterpiece Twin Peaks in the ’90s. A mutual friend introduced them and they hit it off, first working together on a promo for a prune farming operation in Yuba City. Gonzo eventually asked Tokuno if he might be interested in lighting a music video for a local band.

“It was absolutely symbiotic,” Tokuno says. “I daresay I might have taught him a few things, but to be clear, he’s always had a vision. He’s like an iceberg: What you see on top doesn’t even scratch the surface of how deep he is.”

The collaboration gelled. Gonzo got an agent in 2010 and he and Tokuno have made nearly a hundred music videos together since. And in parallel, Gonzo began to develop his unique style as a fine art photographer. Tokuno compares Gonzo to another friend—the late, iconic German fashion photographer Helmut Newton, whose transgressive brand of stylized, fetish-chic noir was so widely imitated that he inspired as much fashion as he captured in images. Tokuno believes Gonzo is already influencing other artists like that. “I explained to him that it’s flattering,” he adds. “[He’s] inspired them. If you’re going to copy something that Raúl does, then you’re steps behind him, because he’s on to the next thing.” One of Gonzo’s prized possessions is a Rolleiflex camera that once belonged to Newton, gifted to him by Tokuno.

Parked Car for Dinner, Part 1 is one of the 25 works that will be on view at Gonzo’s new Color Madness exhibit at the Crocker Art Museum. (Courtesy of the Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist)

In 2014, shortly after the end of a long-term relationship and the birth of his third child, Gonzo lit out for the big city again—Sacramento this time. Today, Gonzo is in a new relationship with a grade-school teacher. His 24-year-old son Ashton hopes to enter the police academy soon, while daughter Piper turns 24 in July and is a real estate agent like her mom, and 14-year-old Dimitri splits his time between West Sacramento with his dad and Yuba City with his mom.

Without any formal diagnosis, Gonzo suspects himself of being neuroatypical, and that tracks with the myriad minor obsessions that fill his days. “I’m a creature of habit,” he explains. “So there are 30 things I like to do every day.” He practices the keyboard. Then his languages—Japanese, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Ukrainian and American Sign Language. (“I love learning languages,” he says. “I’m just not good at any of them.”) Then he might take a Kenpo karate class, or go to the library, or sit and sketch with a hot chocolate at Old Soul Coffee at the Weatherstone on 21st Street, or take Dimitri to the roller rink, where they are learning to skate. “Roller skating is my thing now,” he says.

There’s also a half-time day job that pays the bills, at Moonracer Films, where he makes educational videos for entities like the Clean California campaign and the California Community College Chancellor’s Office. During the hiring process, he says, “They said, ‘This is not creative work, are you up for it?’ And I said, ‘Believe me, I need the balance.’ ”

Early on in the pandemic, Gonzo also branched out into stand-up comedy, taking classes from local comedians Melissa McGillicuddy and Johnny Taylor Jr. and attending open mic nights at Vince’s Ristorante in West Sacramento. “My initial impression was that his comedy was so different,” says Taylor, who appeared in the 2021 “California” music video that Gonzo directed for Saturday Night Live alum Melissa Villaseñor. “I didn’t necessarily know if it was good or not, but I thought it was unique. There were a lot of ideas, and a lot of creativity; he’s one of the most creative people I’ve ever met.” One of Gonzo’s most successful bits was bringing an easel on stage and flipping through his photographs with a running commentary. “The through-line is his art,” Taylor says. “He’s a visual storyteller.”

On stage, Gonzo often wears his “skeleton suit”—a black business suit printed with a red skeleton. “I love that suit so much,” he says. “I definitely want to be buried in it. A comedy funeral would be really funny.”

Gonzo, who started performing stand-up comedy during the pandemic, wearing his go-to stage uniform, a beloved skeleton suit (Courtesy of Raúl Gonzo and the Crocker Art Museum)

That sense of humor crosses over into his visual art, which is part of what drew the attention of the Crocker’s chief curator Scott A. Shields. Gonzo was inspired to approach the museum after seeing the 2017 show Turn the Page: The First 10 Years of Hi-Fructose Magazine, featuring artists from the influential art periodical, including pop surrealists like Mark Ryden and Todd Schorr, along with an immersive installation by Mark Dean Veca where visitors could lounge in beanbag chairs surrounded by a riotous graphical colorscape. These artists were Gonzo’s people. It took a while, but in 2020, he put together a presentation deck—he knew how to sell an idea from building hundreds of concept presentations for music videos—and sent it to the museum.

Shields liked what he saw. “The work speaks for itself,” he says, adding that Gonzo continues a regional tradition of weaving humor into otherwise serious fine art, from Roy De Forest’s grinning, cartoonish wild dogs to Robert Arneson’s porcelain toilet sculptures (not to mention the Egghead sculptures scattered about the UC Davis campus) and Mike Henderson’s watermelon-eating spin on The Last Supper. Indeed, when De Forest, Arneson, Henderson, Wayne Thiebaud and William T. Wiley joined the fledgling art department at UC Davis in the ’60s and early ’70s, they were starting with just a Quonset hut at an agricultural college—hence the style that Wiley dubbed “Dude Ranch Dada.” Shields notes this heritage in Gonzo’s take on the NorCal tradition. “There’s a lot of nostalgia about the images,” he says. “And a little bit of Stepford Wives,” referring to the campy 1975 horror film in which suburban housewives are replaced by perfect robots. “There’s also a strong ’80s MTV quality,” Shields adds. “Devo comes to mind.”

Francesca Wilmott, the Color Madness curator, sees a show like Gonzo’s as critical to the Crocker’s mission. “The Crocker has always been a contemporary institution,” she says. “When the Crocker family started collecting in the mid-1800s, they were collecting the art of their time. Thomas Hill was acquired the year the work was painted, same for Charles Christian Nahl. They were taking risks. There are other [more contemporary] examples. Like in our Black Artists in America show, we have a Betye Saar piece that was made in 1975 and acquired in 1975. So, what does that mean today? How can we carry forward that legacy?”

And as Shields points out, the Crocker gave a young Thiebaud his first solo museum show, too, in 1951—not all that long after the artist was selling his early paintings in a Safeway parking lot.

![]()

A few days after the tour of his house, Gonzo offers a tour of his professional photography studio in an industrial park near the Cal Expo-area Costco. This warren of studios, soundstages, dressing rooms, offices and prop rooms is where he shoots most of his photos and music videos—he is in demand enough that his collaborators, including the Goo Goo Dolls and Kat Von D, have come to Sacramento to work with him. Props from his old sets still sit piled on top of some cabinets in one storage room—there’s a gold-painted cello, a blue bird in a hot pink cage, a green bicycle with square yellow wheels. He points out a loft where he used to spend many hours immersing himself in sketching, creating and photographing almost daily, dashing down to set up shoots spontaneously. These days he only arranges shoots for his still photographs around twice a year, both because the elaborately staged images are so expensive to set up, and because 10 years in, he’s still increasing the complexity of each concept.

Standing on an empty soundstage between a green screen and a cornerless white backdrop, he shows a sketch for an image he’ll shoot in July. It’s a diorama mashing up figures with furniture—kind of like the anthropomorphized furniture in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, but with a surreal, sinister streak. A model with a set of dresser drawers for a body is looking down into an open top drawer at a pair of balloons nestled inside. The balloons could be breasts (the joke might be a “chest” of drawers), and the model’s hand is poised to pop them with a pin. It could easily be a scene out of Luis Buñuel’s seminal Un Chien Andalou—the 1929 surrealist short film co-written by Salvador Dali, based largely on fragments of the two artists’ dreams.

Needless to say, it takes a special kind of model for a Gonzo shoot. One such model, Mosh—a mononymous former gymnast turned burlesque star—acts as muse for her frequent collaborator. “He hired me for a music video, had me put my finger on a record player like I was a Victrola machine, and we’ve been friends ever since,” she says on a call from Los Angeles, where she lives.

Mosh has her own theory as to why Gonzo’s superficially cartoonish work has so much soul. “Some photographers really objectify their models, not in a derogatory or malicious sense,” she says. “It’s just that they kind of use them as a tool and an extension of themselves, rather than seeing them as individuals. I’ve never once felt like Raúl just wanted me to do something because I was the mannequin of the day. He has respect for who he’s photographing, that they’re a living, breathing, organic life form. Raúl utilizes that to his advantage, immersing the model in his world—and then he gets these results.”

When you see Mosh in the photograph titled Mars Vixen, wearing a red patent leather catsuit and brandishing a ray gun à la Jane Fonda in Barbarella, she’s very much the subject of the image, not the object. Gonzo may have painstakingly created the world for the image, but he also created it for her to inhabit wholly, so there’s a lot going on behind those perfectly made-up eyes when the shutter snaps.

In the foreword to Gonzo’s 2021 coffee table book for his Color Madness series, television writer and producer Andy Reaser (Grey’s Anatomy and Pretty Little Liars) wrote of these female figures, “While in some images they seem to play up to expectations of their lives, in others we almost sense them planning an escape, working out the complexities of seeing the artifice in their lives. This makes the people living in this dream incredibly human to me. There are realities we could never bear without building ways to process and cope with them. We add color, we add chaos, we do whatever we can to distract from the fact that we want what we resent, we fear what we love….”

Favorite Show Canceled (2015), also part of the Color Madness series (Courtesy of Raúl Gonzo and the Crocker Art Museum)

Wilmott compares Gonzo to the photographer Cindy Sherman, whose body of work consists entirely of self-portraits in costume as various personae—some beautiful, some grotesque, ranging from a 1960s Italian movie star to a dewy schoolgirl to a circus clown to a corpse. What makes them so compelling aren’t the costumes and set pieces, but how the artist inhabits them, as if each were a privileged glimpse into her inner life, the self the world never sees. Gonzo’s work shares that quality of using outward spectacle as a window into a rich inner landscape—because that is, after all, what art does best.

Luis Buñuel once said, “Give me two hours a day of activity, and I’ll take the other 22 in dreams—provided I can remember them.” With an idea between his teeth, Gonzo would probably also spend 22 hours a day in Dreamland if he could—the twist being that most of his real-life activity unfolds as if in a dream.

“I just became obsessed with this,” he says, gesturing to the empty stage where the sketch on his phone will soon burst forth into full, flagrant reality. “I’m so excited to do it. When I have an idea, it’s the thing that gets me up in the morning like a kid on Christmas Day.”