Man. Verses. Nature.

Like the ripple effect of a pebble dropped into the still water of a pond, Gary Snyder’s outsized influence extends far beyond the edges of his remote, hand-built home in the woods near Nevada City. At 92, the poet and environmentalist has lived an extraordinary life—from birthing the Beat Generation with fellow writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg to winning the Pulitzer Prize for his book Turtle Island, which has been described as a “poet’s love lyrics to planet Earth,” and even inspiring the release of the Pentagon Papers. With two new major anthologies out, this former UC Davis professor is proving that he still has a lot to teach us all.

On a crisp, sunny morning in May, the approach to Kitkitdizze—poet Gary Snyder’s homestead named for a native species of evergreen rose—passes through several landscapes: a pretty two-lane road winding through cathedral-like forest, over rugged creek and river crossings, through the rural hamlet of North San Juan, slightly hippieish around the edges, and eventually through “the diggins,” an eerily pretty, mining-scarred sandscape that is slowly rewilding itself. It’s only 15 miles from Nevada City, but the circuitous, bumpy trip takes over 40 minutes, and Google Maps won’t get you there.

“He used to have a map to his house, and at the bottom was a line that he wrote out saying, ‘If captured, eat this map,’ ” remembers Snyder’s longtime friend and publisher Jack Shoemaker, citing Snyder’s zeal for privacy before pointing out that he has never been a hermit. “Gary has lived a relatively isolated life, but he could use his celebrity to good effect, personal and political, when he wished to. When you got to Gary’s house in the woods, however hard it was to find, Jerry Brown might be there or Stewart Brand [publisher and editor of the Whole Earth Catalog] might be there, or any number of famous people from the ’60s.”

Suddenly, past a clump of trees, there it is—a rustic house with deep eaves, surrounded by matching outbuildings: a shed, a free-standing covered porch, a garage housing an old pickup truck, an outhouse.

From the outside, the house is unassuming, with a red-tiled roof, solar panels, and ordinary stained wood siding. The deep front porch is stuffed with galoshes and snowshoes, a practical place to gear up or down in season, antlers over the front door, which Gary Snyder answers.

His face has an elvish triangularity to it, with merry eyes and curling lips over a bearded chin. Here, he is just another woodland creature: larger than a wolf, smaller than an elk, to quote the title of one of his essays exhorting us to be less human-centric in our cosmology. At 92, Snyder has an older man’s spine, curved elegantly like a violin bow, making him look a bit like a character out of a traditional Japanese watercolor, if only he were wearing a kimono and carrying a staff. But he is nattily dressed in olive green shorts and shirt, and a chunky maroon sweater vest that I compliment because it is stunning and obviously something special.

“My late wife Carole knit that,” he says fondly. “It’s a little heavy, but it’s good for some things. She had fun with it anyway. She never counted herself a super seamstress, but she sure was better than nothing.” The way he says it, he means she was the best. I like him.

“I have something to show you,” I say by way of an icebreaker, pulling a first edition of his second poetry collection, Myths & Texts, out of my bag. “My mother bought this at one of your readings in Eugene or Portland, in the ’60s.”

His eyes crinkle in delight. “Oh, neat!” he says, thumbing through the yellowed, staple-bound paperback with a coffee stain on the paper cover. “That’s old.”

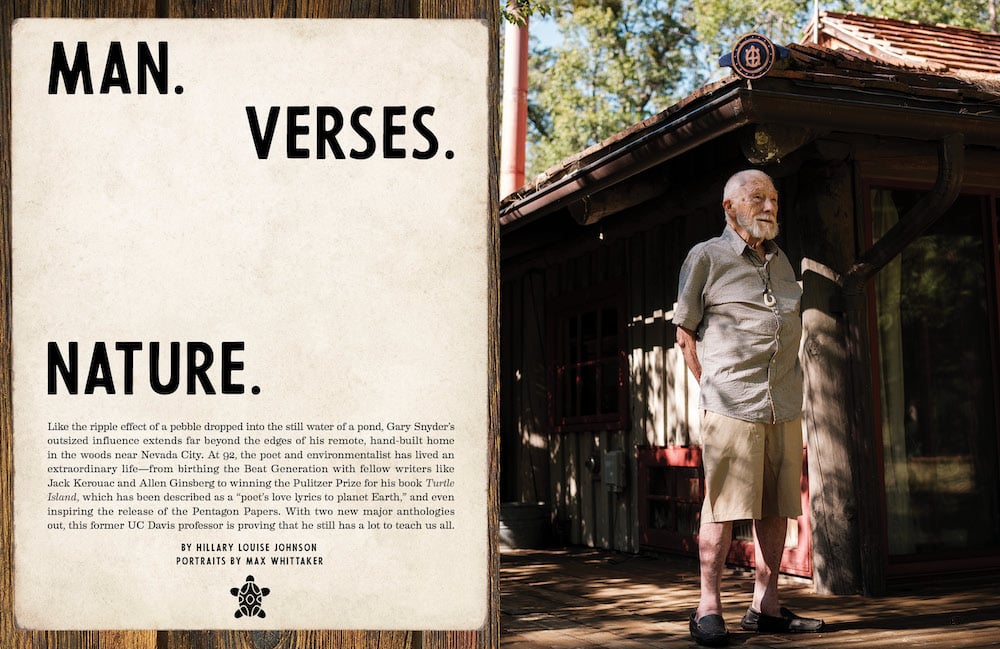

Gary Snyder, 92, photographed on June 16 at his home outside Nevada City, where he has lived for over 50 years (Photo by Max Whittaker)

It’s funny to hear a great man of letters use the word “neat” the way a kid would, but Snyder’s speech is simple and colloquial. Around North San Juan and Nevada City, he’s just a guy the neighbors know as “Gary.” The literary reputation, he says with a dismissive wave, “is nothing they need to pay attention to.” Except that they do. My dad’s occupational therapist in Washington state grew up in Nevada City, and has proudly told me about her collection of Snyder’s first editions. The Pulitzer Prize-winning Beat poet is a household name in Nevada County.

“I want to show you these two books,” he says, gesturing me over. I expect him to show me galleys of his own forthcoming works, but they are both by his friend, the celebrated Davis-based sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson: The High Sierra and The Ministry for the Future. “I’ve read the first, but not yet the latter. It’s a big book. I’ve only read two chapters,” Snyder says, “but I’m going to go through it because I can see that it’s really thorough. I’ll learn as much from this as I’ll ever learn about global warming.”

He isn’t wrong about the breadth of Robinson’s knowledge, but he also knows a thing or two about global warming.

Robinson tells me later he happened to be out hiking on the flank of a volcano with Snyder when he got the call that every writer dreams of—news of a life-changing multi-book deal— and felt some sense of importance of reaching that milestone with one of his heroes by his side like a shamanic spirit guide. “That moment was a Gary Snyder moment for me,” he says. “It seemed to put a magical spell on that whole phase of my career.”

I am right now also a writer sizing up one of my childhood heroes in the flesh. I had recently re-read Jack Kerouac’s novel The Dharma Bums, a roman à clef that describes the Beat culture in detail, so its most iconic scene is fresh in my mind: Japhy Ryder—a thinly fictionalized version of Snyder—leads a hike to the top of Yosemite’s jutting, 12,000-foot Matterhorn peak, leaping from boulder to boulder, and at one point hiking in nothing but boots and a jockstrap. When Kerouac’s protagonist Ray Smith first meets Ryder/Snyder in the book, Kerouac describes him as “wiry, suntanned, vigorous, open, all howdies and glad talk and even yelling hello to bums on the street and when asked a question answered right off the bat from the top or bottom of his mind I don’t know which and always in a sprightly sparkling way.”

DHARMA BUMS

Gary Snyder was an unpublished 25-year-old poet living in the Bay Area on Oct. 7, 1955, when he stood up at a gathering of young poets in San Francisco and had to follow one of the most legendary moments in the history of poetry.

Allen Ginsberg, then 29, had just sent the group assembled at the Six Gallery on Fillmore Street into a literary frenzy, when he read—for the first time—his now-iconic epic poem “Howl,” which begins:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz

A 33-year-old Jack Kerouac (he would publish his breakout novel On the Road two years later) passed around jugs of red wine and led the crowd in finger-snapping chants of “Go! Go! Go!” as Ginsberg read his career-defining work.

That moment ushered what would be known as the Beat Generation into ascendance. These were poets and writers who ran counter to the mainstream of post-war America, when Pat Boone and Frank Sinatra topped the charts, before Elvis gyrated on national television or the hippies tripped on Haight-Ashbury.

In a 2010 documentary about Snyder—Practice of the Wild (the title borrowed from the poet’s 1990 essay collection of the same name)—the late Michael McClure, one of the five poets who read that evening, described how Snyder stole the show. “Allen Ginsberg read ‘Howl’—a very famous poem, probably the most popular poem in the world today,” McClure said. “That same evening Gary Snyder read his very deep and important poem … and in that audience, many of the people who were terribly moved by ‘Howl’ were even more moved by ‘A Berry Feast’ by Gary Snyder.”

It starts:

Fur the color of mud, the smooth loper

Crapulous old man, a drifter,

Praises! of Coyote the Nasty, the fat

Puppy that abused himself, the ugly gambler,

Bringer of goodies.

In bearshit find it in August,

Neat pile on the fragrant trail …

Blackbear

eating berries, married

To a woman whose breasts bleed

From nursing the half-human cubs.

The poem anthropomorphizes animals and zoomorphizes humans, is mythic and epic, carnal and sly all at once. It’s hard to appreciate in hindsight how groundbreaking it must have seemed in that moment, folding Native American lore, Zen thought, and colloquial, lumberjack-swaggering rawness all together, the whole tumble-jumble of sacred and sexual read out loud by a slight-framed, impassioned poet with a surprisingly sonorous voice.

Kerouac clearly understood the importance of the charismatic performance he was witnessing, and included this description of Japhy Ryder-cum-Gary Snyder’s Six Gallery reading in The Dharma Bums:

“His voice was deep and resonant and somehow brave, like the voice of old-time American heroes and orators,” Kerouac wrote, “Something earnest and strong and humanly hopeful I liked about him, while the other poets were either too dainty in their aestheticism, or too hysterically cynical to hope for anything.”

The poet, seen here wearing a kimono in Kyoto, resided mostly in Japan from 1956 to 1969. (© Allen Ginsberg/Corbis via Getty Images)

New York writers had been chilling in Greenwich Village for years with such cynical detachment, but the Six Gallery reading brought something new into being: It turned poetry into something as cool, dirty and edgy as rock ’n’ roll, but also infused it with a socially conscious, eco-focused, culturally eclectic, Left Coast energy—the opposite of detached, dainty aestheticism. McClure later called “A Berry Feast” “the first poem of ‘deep-ecology.’ ” The term, later coined by Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1972, put a name to a growing sense that humanity and wilderness should not be posited as bicameral ideas—tame vs. wild, civilization vs. nature—but rather that the planet is one holistic ecosystem of which humans are but one component.

Snyder introduced “civilized” writers like Kerouac and Ginsberg to Zen and the Wild West. He and Ginsberg in particular fell into a fast friendship when they met in 1955, one that lasted until Ginsberg’s death in 1997. “We argued a lot and were not easy on each other. I made him walk more, and he made me talk more,” Snyder wrote in the introduction to The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, 1956-1991. “It was good for both of us.” Along with Kerouac, they hitchhiked and hiked up and down the West Coast, alternating between meditating, mountain climbing and carousing.

Then Snyder left the Bay Area in 1956 and spent most of the next 13 years in Japan, studying Zen and translating Chinese and Japanese poetry, venturing back to the United States multiple times during that span before returning for good in 1969.

“When Gary came back to San Francisco, having lived all that time in Japan, he came into an environment that was a hotbed of celebrity,” explains book publisher Jack Shoemaker, the co-founder of North Point Press and Counterpoint Press. “On the poster for the Gathering of the Tribes, Gary’s name is the same size type as Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. I’m looking at it right now.” He’s talking about the 1967 “Human Be-In” (a play off the “sit-in” protests of the ’60s and the word “being”) in Golden Gate Park—one of the inaugural events of the hippie movement, where the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane serenaded a crowd numbering in the tens of thousands. It led to the Summer of Love, and Snyder was smack in the middle of that catalytic gathering.

“But his choice at that stage was not to stay in the city. He opted to become a homesteader in the mountains,” Shoemaker adds, referring to Snyder’s move to the Sierra foothills in the 1970s.

Today, Snyder is still a mountain man, and one of the lesser known yet one of the most celebrated of the Beats. He won a Pulitzer Prize—the lone member of the Beats to do so—in 1975 for his poetry collection Turtle Island (Native American mythologies depict North America as the back of a giant turtle) and the American Book Award in 1984 for his collection Axe Handles.

And this year, the prestigious Library of America released a definitive 1,000-page volume of his works, Gary Snyder: Collected Poems, on June 21. (Some of the other collected volumes published by Library of America this year have been for John Updike, Maxine Hong Kingston and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Last year’s featured authors included W.E.B. Du Bois, Ray Bradbury and Sacramento’s own Joan Didion.) On Aug. 16, Counterpoint Press released Uncollected Poems, Drafts, Fragments and Translations—a compilation of never-before-published works by Snyder.

His influence on his readers and fellow writers can’t be overstated. In a 1996 story for The Paris Review, the celebrated writer Eliot Weinberger called him “a rarity in the United States: an immensely popular poet whose work is taken seriously by other poets.” He also wrote, “He may well be the first American poet since Thoreau to devote a great deal of thought to the way one ought to live and to make his own life one of the possible models.”

Snyder and poet Allen Ginsberg walking in the North Cascades in 1965 during a backpacking trip (© Allen Ginsberg/Corbis via Getty Images)

Dipping into the 1,000 pages of his collected poems—poems that I, as a child in the 1960s, grew up on—gave me a mnemonic shock: Here were sounds and images from an era that’s been so successfully repackaged as “nostalgia” that we barely remember what it was really like, or really about. This was a time when actions were important, and poems were actions.

In a 2005 interview with the online climate-focused magazine Grist, Robert Hass—the former United States Poet Laureate who wrote the introduction to the newest reprinting of Snyder’s 1990 essay collection, The Practice of the Wild—declared that “the great poet of the environment of this era is Gary Snyder,” before proffering the best explanation I’ve heard to date of just how poetry can and does effect change. “Ideas matriculate slowly through poetry into the general culture,” he said. “Wordsworth read the German Romantics … Thoreau read Wordsworth, Muir read Thoreau, Muir preached the gospel of Yosemite, and we got our national park system.”

ALL TRUE PATHS LEAD THROUGH MOUNTAINS

In 1966, Snyder, Ginsberg and a handful of other friends chipped in to buy a 100-acre parcel on San Juan Ridge just above the Yuba River, a few miles from Nevada City, with the intent of forming a progressive, off-the-grid community where writers and artists could live close to nature.

Snyder’s first collection of poetry had been published in Japan seven years earlier, in 1959. Riprap was inspired by summers spent working on a trail crew in Yosemite and as a fire lookout atop peaks in Washington State’s rugged North Cascade mountains. Snyder was newly married to Masa Uehara, and the couple had a baby boy, Kai. (Snyder sent baby pictures to Ginsberg, writing, “Fatherhood is like having a Zen master in the house all the time. Talk about dignity, demands, nonverbal communication; and a mirror held up to yourself.”)

The land that the group settled on was still recovering from the abuses of the 19th-century Gold Rush (think primitive fracking), and completely undeveloped—dirt roads, no water, no electricity, no phone lines. But Snyder liked the flora, the altitude felt right, and he was ready to make a commitment.

Ginsberg spent time there and even built a small cabin for his occasional visits, but the Beats were nothing if not a perpetual motion machine—not big on cleaving—so Snyder was the only one of the original gang for whom the rural lifestyle really took, and he bought out Ginsberg and some of the others eventually.

Snyder’s house at Kitkitdizze (pronounced kit-kit-dizzy), which had appeared modest from the outside, proves marvelous on the inside with a soaring, timbered ceiling, every beam a whole hewn log. He goes to a bookshelf and pulls out a grainy photo from the early ’70s that depicts shirtless bearded hippies building the frame of the house, sinking posts and laying beams. “All of this house was built by me and my friends, and all of the trees came from the hills around here,” he says.

The dining table sits centered in the house under a raised, skylit cupola whose sides were once open to the elements. “We had a firepit in the middle,” he explains. “At one time, you would just sit on the floor around the fire and the kettle, which hung from the ceiling and boiled.”

It’s a bit like a Native American teepee, built around a flame for hearth and home. It would have been a lifestyle that required constant tending—a good metaphor for Snyder’s extreme dedication to the art of daily living, the joy he takes in the smallest of rituals and ablutions. Snyder didn’t install an indoor toilet and bath until 1997, using money from a literary prize.

One of his best-known poems is “The Bath,” from Turtle Island, his book that won the Pulitzer in 1975. Snyder donated the $1,000 prize money to help build The Oak Tree School, for elementary and middle school students, in North San Juan.

The Christian Science Monitor called Snyder’s Turtle Island poems “love lyrics to planet Earth.” “The Bath” is a paean to domestic bliss involving the young Snyder family—Gary, Masa and toddler sons Kai and Gen, starting out…

Washing Kai in the sauna,

The kerosene lantern set on a box outside the ground-level window,

Lights up the edge of the iron stove and the washtub down on the slab

Steaming air and crackle of waterdrops brushed by on the pile of rocks on top

He stands in warm water

You can smell the steam—the family bath emblematic of the Zen virtue of being present in the moment. “Gary wrote a very plain American English that was not mannered,” Shoemaker says. “And he wrote about domestic matters. I’ve often thought he was the best domestic poet of his time.”

SMOKEY THE BEAR SUTRA

I’ve brought sandwiches, berries and matcha from the closest store, a natural foods market called Mother Truckers, for our lunch. “We can put the food and drinks out here,” he says, pointing to the dining table. “To do the actual interview, we’ll go back to my office,” Snyder suggests, beckoning me to follow. “Let’s do the talking first.”

On the way, we pass a window and he pauses, gesturing to the spot 50 yards away where the crooked old outhouse sits—a long walk on a snow day, I’m thinking. “That toilet would be usable if it wasn’t leaning at an angle,” he says. “The reason it’s tipping is my own fault, an error in judgment. The tile roof is too heavy. I’m going to fix that up. I would use it if it was in good condition.”

Snyder (second from left) with four of his fellow California Hall of Fame inductees—(from left) NFL great Jim Plunkett, director Steven Spielberg, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and pioneering winemaker Warren Winiarski—at the California Museum on Dec. 5, 2017 (Photo by Robert Durell, courtesy of the California Museum)

We enter an addition built in 1997 with the cash award he received from Yale University’s Bollingen Prize for Poetry. There’s an indoor loo to one side, then a short hallway opening into two small rooms with vaulted ceilings and modern drywall trimmed in honey-colored wood. Every horizontal surface in the main room is covered in stacks of papers and books. In the alcove beyond, there’s a comfortable reading chair and a Mission-style single bed neatly made with a Pendleton wool blanket—very lumberjack-monk.

“This is kind of messy right now,” he apologizes. “I’m organizing and reorganizing, giving things away a lot, getting things out and looking at them, thinking… Oh, there’s Smokey the Bear!” he exclaims, pointing at the T-shirt I wore today in honor of one of my favorite Snyder works, “Smokey the Bear Sutra.”

“I traced the mythological background of bears in Native American culture and made this entirely new story,” he says. “People really enjoyed it; people in the Forest Service too.”

Snyder wrote it in 1969, right after he returned to San Francisco from Japan, inspired by a poster he saw depicting Smokey Bear—what a jaunty fellow, with his ranger hat, dungarees, shovel and salute of greeting! Snyder had an epiphany, deciding in a thunderclap of an aha moment that the U.S. Forest Service had unwittingly revivified what some believe to be one of the world’s oldest religions—the cult of the bear. In essence, the original Buddha.

So he dashed off his sutra (aka Buddhist scripture), made his copies and handed them out the next day in the lobby of the hotel hosting the Sierra Club’s Wilderness Conference. The writing is slow burn, deadpan funny, tongue firmly planted in cheek. Its opening lines:

A handsome smokey-colored brown bear standing on his hind legs, showing that he is aroused and watchful.

Bearing in his right paw the Shovel that digs to the truth beneath appearances; cuts the roots of useless attachments, and flings damp sand on the fires of greed and war;

His left paw in the Mudra of Comradely Display–indicating that all creatures have the full right to live to their limits and that deer, rabbits, chipmunks, snakes, dandelions, and lizards all grow in the realm of the Dharma

It’s a protest song about man’s disregard for nature—fashioned with a wink and a nod to the Forest Service’s public service messaging. That’s Snyder’s sense of humor, both quick and heavy, like a stone skipping over the surface of a deep, deep pond. He is somehow always joking but never kidding, a scholar with the instincts of a showman to always leave ’em wanting more.

“Smokey the Bear Sutra” was a serious work of protest literature, exhorting us to become stewards of the environment before it was too late. There Snyder was, standing in front of the Sierra Club papering its members with leaflets about the coming scourge of global warming—eight years before that prophetic 1977 memo whose subject line alerted then-President Jimmy Carter to “the possibility of a catastrophic climate change.”

I tell Snyder that a bear paid a visit to my campsite the night before, almost as if it were a bear shaman sent to bless the interview. He shares that he himself has a bear and three cubs who sometimes visit. Then I take the seat offered beneath his Buddhist altar, gesture at it and ask, “What is your daily practice?”

“Well,” he says, “the daily practice is the daily practice, and that’s every day.” A typically laconic Snyder approach to questions: he dissolves them rather than replying to them. Then he takes pity on me and answers: “I light a stick of incense, light a candle, and on certain days we have somewhat more complicated things we’d do. We have a zendo down the trail that will seat 80 people. It’s not mine personally, it belongs to the community.”

The Ring of Bone, as the zendo—or meditation hall—is known, developed organically after the group that gathered regularly at his home grew too big to squeeze in around the Snyder home firepit. Snyder and Uehara divorced amicably in 1989; he then married fellow Ring of Bone attendee Carole Koda in 1991, and Uehara married Snyder’s friend Nelson Foster, who runs the zendo. Everybody lives on the property, as do Snyder’s sons Kai, now 54, and Gen, 52, who lives in Ginsberg’s old cabin. Koda passed away from cancer in 2006.

Snyder wrote about his creatively construed ménage in a poem called “Waiting for a Ride” that was published in The New Yorker in 2004:

My former wife is making websites from her home …

My wife and stepdaughter are spending weekdays in town so she can get to high school …

My former former wife has become a unique poet

That last line refers to the late Joanne Kyger, to whom Snyder was married from 1960 to 1965. The then couple had traveled to India with Ginsberg and his boyfriend, poet Peter Orlovsky. Kyger wrote a well-regarded literary memoir along the way in which she documented how difficult young male poets could be to travel with—how Snyder thought he was always right about everything, like most husbands of a certain generation, and how Ginsberg’s ego was so great he wanted to read “Howl” to everyone they met—including the Dalai Lama.

Snyder in Kyoto in 1963 with his then-wife Joanne Kyger, who was also a poet and later published the literary diary The Japan and India Journals 1960-1964 (© Allen Ginsberg/Corbis via Getty Images)

“The Dal is 27 and lounged on a velvet couch like a gawky adolescent in red robes,” Kyger wrote in her journal, published in 1981 as The Japan and India Journals 1960-1964. “I was trying very hard to say witty things to him through the interpreter, but Allen Ginsberg kept hogging the conversation by describing his experiments on drugs and asking the Dalai Lama if he would like to take some magic mushroom pills.” Then she went on to describe a very different conversation: “Gary and the Dalai [were] talking guru to guru like about which positions to take when doing meditation and how to breathe and what to do with your hands.”

That’s Snyder—ever practical and how-to minded, even in an audience with the Dalai Lama. The poet Kenneth Rexroth wrote about this Boy Scout tendency in an essay titled Smokey the Bear Bodhisattva, sharing an anecdote that perfectly captures why Snyder made a better homesteader than he ever would a hippie: “When Snyder some years ago in the Early Flower Children Days visited one of the first communities of love in the wilderness, he said, ‘Gee, you ought to build a couple of latrines.’ An otherwise nude girl wrapped in a torn lace curtain said, ‘What’s a latrine?’ Snyder went and got a shovel.”

DANGER ON PEAKS

Snyder was born in San Francisco in 1930, and two years later the family went to ride out the Great Depression on a small dairy farm just north of Seattle. His mother Lois was an enthusiastic atheist (he has said she shrugged off his Buddhism as “navel gazing”) with socialist leanings. The forest was his playground, and his earliest companions were books and trees. When his parents divorced in 1942, his mother moved Gary and little sister Anthea to Portland and took a job as a newspaper reporter just across the Columbia River in Vancouver.

In high school, Gary discovered mountaineering and poetry simultaneously. He climbed Mount St. Helens for the first time at 15, an experience that opened a majestic vista of awe and possibility, as he described 60 years later in a prose poem: “…the big snowpeaks pierce the realm of clouds and cranes, rest in the zone of five-colored banners and writhing crackling dragons in veils of ragged mist and frost-crystals, into a pure transparency of blue.”

He came down from that mind-expanding climb to newspaper reports of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and his heart collapsed in grief and anger. He vowed “by the purity and beauty and permanence of Mt. St. Helens, I will fight against this cruel destructive power and those who would seek to use it, for all my life.” St. Helens, of course, was far from permanent, erupting so violently in 1980 that the top third of the mountain was blown clear off, forever altering the natural skyline of the Cascades. The St. Helens cycle of poems from Danger on Peaks (2004), captures the bitter poetry of the closed circle:

Roiling earth-gut-trash cloud tephra twelve miles high

Ash falls like snow on wheatfields and orchards to the east

five hundred Hiroshima bombs

But just when the tone feels set to swell into elegy, Snyder feints, escaping the bitterness of the human experience of disaster by taking the point of view of the mountain—a different scale and time frame. A mountain always accepts change with grace, whether glacial or catastrophic. There is still time for joy and peace. He pulls this off through clever little elisions. Snyder’s poetry is oddly difficult to quote in snippets: it’s a little like trying to convey the graceful lope of a bear from a paw print, or the shimmer of an aspen grove from a single fallen leaf. The moment you break off a chunk, the greater sum of the parts dims ever so slightly. He is best read whole. Preferably after a vigorous climb up a mountain.

In 1947, Snyder enrolled at Reed College in Portland, an ivy-covered institution with a reputation for rigorous academics and maverick independence (Steve Jobs and James Beard went there) and it was at the school where he formed a close and enduring bond with his roommates—poets Philip Whalen and Lew Welch. For his first summer vacation, he hitchhiked to the East Coast and got a job on board a ship sailing to the Caribbean. The next summer he worked on a Forest Service trail crew. In 1950, he married a fellow student who left him after just a few months, and in 1951, at 21, he graduated with a degree in Literature and Anthropology.

Snyder would bounce around between San Francisco, Japan and the Pacific Northwest for the rest of his early adulthood. He enrolled in Chinese language studies at UC Berkeley for a while. He brought Kerouac up to the North Cascades, where they each manned a fire lookout atop a lonely peak. He worked felling trees. He led hikes into the Sierra and around Mount Tamalpais.

Printmaker, historian and scholar Tom Killion, 68, who has become a close friend and travel companion over the years, became enamored of Snyder’s poetry as a Marin County teenager—a prime exemplar of the generation of creatives most affected and influenced by Snyder. “I think he’s the single most important intellectual figure of the West Coast counterculture in the 20th century,” Killion says on a call from his art studio near Point Reyes. “The Dharma Bums had an immense impact on people like me who were looking for something, and that was just Kerouac channeling Gary. Yeah, Kerouac was a great writer, and he made it really readable, and he added a lot of little spicy things that Gary repudiates as being untrue, but what I got out of it was the rucksack revolution [a rucksack is nearly synonymous with backpack]. Gary always used metaphors from backpacking [in his poetry], which I just loved because that was such an important part of my teenage years and early twenties, just putting on a pack and wandering the world and the mountains. He was my intellectual guide through all that.”

Snyder and Killion have collaborated on three coffee table books, and often travel together to visit national forests. On their trip to see the giant sequoias just last year, Snyder gave an impromptu reading from Turtle Island for a group of four or five Forest Service rangers:

I recalled when I worked in the woods

And the bars of Madras, Oregon.

That short-haired joy and roughness–

America–your stupidity.

I could almost love you again.

We left–onto the freeway shoulders–

under the tough old stars–

COYOTE FINDS THE WATERING HOLE

Snyder was a mentor to many more than Killion, including Davis sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson, who shares Snyder’s interest in ecology and whose most recent novel, The Ministry for the Future, landed on former President Barack Obama’s list of favorite books of the year in 2020. “I was a young man. I wanted to be a poet. I ran into Buddhism and Gary’s work when I was an undergraduate,” Robinson says from his home, where stones collected on visits to Kitkitdizze over the years comprise part of his flagstone patio. “All the models for being an American writer were not particularly healthy: Hemingway, Kerouac. There was a bunch of alcohol and womanizing and guns and ego battles.”

He laughs. “And then Gary was just like, ‘I spent ten years in a Zen monastery in Japan, and I’m bringing up my boys. I’ve got my wife, I’ve got my land, I’m writing, I’m chopping wood and carrying water’—literally as well as in the Zen saying,” Robinson continues. “For me, that’s how to be a California writer. It was anti-New York—the New York culture of TV and advertising and best-sellers and Norman Mailer. Mailer is a great writer, but he was part of that whole scene of ‘Who’s the big dog in American literature?’ Gary taught me that you could dodge all that.”

Robinson finally got to know his idol in 1994, when he participated in a UC Davis poetry workshop course led by Snyder, who had joined the school’s faculty in 1986. “He used to describe his [university] job as ‘coyote finds the watering hole’ because he needed the health insurance,” says the sci-fi author. “But he was an excellent professor—conscientious and scholarly.”

Snyder was as innovative an academic as he was a poet, according to now-retired Davis English professor David Robertson. (Snyder, Robinson and Robertson became a trio of fast friends who still frequently gather at Kitkitdizze for long lunches.) The pair partnered with fellow professor Will Baker to co-create a course called Literature of Wilderness, and eventually an interdisciplinary major in Nature and Culture that drew on the sciences and the humanities and flourished for 10 years.

And even when Robertson wasn’t designing classes with Snyder, he was teaching Snyder’s work. “I opened to a poem; didn’t really matter which one,” he says, “and I read it as if it was prose and ignored the line breaks and spacing. Then I have a recording of Gary reading it and the students’ eyes always opened wide. My point, you see, was that this is music. Gary’s poems are songs.”

Legendary cartoonist R. Crumb, who lived in Winters for many years, visits Snyder in the greenhouse at Kitkitdizze in November 1980. (Courtesy of the UC Davis Library Archives and Special Collections)

But Davis isn’t the only institution where Snyder has been subject matter. After the breakout success of Turtle Island, Snyder’s next monumental publication was 1996’s Mountains and Rivers Without End, a book-length epic poem that took him 40 years to write. It is dense with literary allusions and inspired a year-long Stanford University research study group that resulted in a scholarly book.

In 2017, Snyder was inducted into the California Hall of Fame in Sacramento, alongside other notable names like Steven Spielberg and the San Francisco Symphony’s Michael Tilson Thomas. Then Gov. Jerry Brown, who first met Snyder in 1974, just before he took office as governor for the first time, delivered the opening remarks. “He is truly a poet of rivers and mountains and the mysterious connections that bind all living beings,”Brown said. “Snyder’s voice beckons us even now to a life of reverence, stewardship and craft.”

Harking back to Robert Hass’ formula, whereby Thoreau and Muir’s literary output led to the creation of the national parks system, Snyder’s legacy includes at least one well-documented instance where he changed the course of history. In 1960, a young man named Daniel Ellsberg, who worked as a military analyst at the Tokyo office of the Rand Corporation, a public policy think tank, recognized “Japhy Ryder” in a Kyoto bar one night, and they ended up talking into the wee hours and all day the next day. “I wanted to see if Gary could convince me of the compelling nature of absolute pacifism,” Ellsberg wrote later of the encounter. He noted that he could not, for security reasons, talk about the nature of his own work on nuclear weapons security, but concluded that Snyder was “a better man than I was. … I was as smart as he was, but he was wise. … He matched the intensity we shared, and the taste for adventure, with a composure, a capacity for sudden calm, a deepness of vision that I lacked.”

They didn’t see one another again until 10 years later, when Ellsberg made a trip to the house at Kitkitdizze just to tell Snyder he’d decided to do something important that might land him in jail, largely due to the fruit born of seeds planted during their brief but meaningful encounter in Tokyo. The Pentagon Papers, which would expose the egregious handling of the Vietnam War, were actually in the trunk of Ellsworth’s car during his visit, after which he went down the mountain, literally and metaphorically, and released them to The New York Times, fully expecting to spend the rest of his life in prison for treason. He was arrested, but ultimately released without charges, although then-National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger did call him “the most dangerous man in America.”

Had Kissinger known the whole story, he might have saved that label for a poet named Gary Snyder.

THE PRACTICE OF THE WILD

Somehow during our own “talking” at Kitkitdizze, Gary and I end up drifting from Smokey the Bear to discussing octopi, and I tell him about the Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher, about a man who forms an emotional bond with a cephalopod, which he’s eager for me to describe. “It’s more or less a love story,” I say.

“That’s not a bad idea,” Snyder says. “The interspecies love story! That’s something we can expect to see in the near poetic future. It may end up being kind of bizarre, but whatever. You can put that on your list of things to be done. I’m not going to live that long.”

“What do you want to do with the rest of your life?” I ask.

“Clean this house!” he exclaims. Then he pauses and speaks earnestly: “I need to thank people. I have a lot of people who have done things for me that I need to thank.”

Snyder works most days, if he’s feeling up to it. He’s writing less original work, and spending more time gathering, annotating and getting his literary affairs in order, and he’s still fired up about new ideas. Today the concept that’s driving Snyder’s imagination is eco-poetry. “We are gradually, without even being quite aware of it, moving from nature poetry to eco-poetry,” he says. “Nature poetry is easily described as the things in nature that we look at and live with, that need protection or need appreciation, from flowers and insects to the birds and hawks and eagles flying overhead. But so now—what is eco-poetry?”

I wait for the answer. “It’s everything. Chemically. At every level,” he says. “It’s what’s going on underneath the soil, just below the surface. This is how you have to see the world as a whole. This is a big step away from human-centeredness. Human beings are just another ant in the forest.”

And yet, I wonder aloud, we may bring about the end of forests. Is he, I ask, worried that we’re facing the end times due to our foolish actions?

“It’s not the end times for humans,” he says. “Humans are too ingenious and clever for that. It might not always be as pleasant as it is right now, but they’ll probably find some pretty smart ways to figure it out.” I note the use of the word “they.” He is passing the baton to younger creatures. At 92, Snyder is older than a coyote, but younger than a redwood. His perspective right now is pretty sanguine. He is adopting the perspective of a mountain or a river without end: this too shall pass, and evolve, and work itself out.

“There’s no need for us to be so worried,” he says, then grins. “So you can turn back to your poetry, and to your art.” By “you,” he means all of us: man, woman, child, bear, coyote.

His words take me back to when I first began preparing for this meeting, many weeks before. I was visiting my mom in Portland, Oregon, and there on her shelves was that 1960 first edition of his poetry collection Myths & Texts, which she bought at a reading when she and my dad were freshmen at the University of Oregon, before I was born. Next to it, my old copy of The Practice of the Wild, which I opened and read:

Life in the wild is not just eating berries in the sunlight. I like to imagine a “depth ecology” that would go to the dark side of nature—the ball of crunched bones in a scat, the feathers in the snow, the tales of insatiable appetite. … Life is not just a diurnal property of large interesting vertebrates; it is also nocturnal, anaerobic, cannibalistic, microscopic, digestive, fermentative: cooking away in the warm dark.

For every lighthearted answer he’s given me today, there’s a deeper, darker, loamier answer waiting to be found—in poetry. And with that, the talking is done. It’s time for lunch—for us to eat berries in the sunlight.