Look Inside Russia's Wildest Nature Reserves—Now Turning 100

Russia is celebrating the centennial of its system of nature protection—including reserves so strict that few people have ever visited them.

Russia’s tumultuous history includes one legacy little known outside its borders—a vast system of protected lands that conservationists have fought for decades to study and protect. Some are so remote and guarded that few of Russia’s own citizens have ever stepped foot in them.

2017 will mark their 100th anniversary—as well as that of the October revolution that ended the reign of the tsars and created the Soviet Union. To commemorate the anniversary, Russian president Vladimir Putin has officially decreed 2017 to be the "Year of Ecology and Protected Areas.”

In January 1917 (technically December 1916, the Soviets later adopted a different calendar), Tsar Nicholas II officially set aside land near Siberia’s Lake Baikal for the Russian Empire’s first zapovednik, or "strict nature reserve." A few months earlier, the United States had established its own National Park Service, with the mission of administering parks "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” as the act establishing Yellowstone in 1872 had put it. The Russian vision was different. (Explore a year-long National Geographic series on the power of parks.)

While the U.S. saw parks as “pleasuring grounds” for recreation-seekers, turn of the century Russian conservationists like Grigory Kozhevnikov had been calling for the opposite—the protection of Russia’s natural wealth from its own people.

“No need to remove anything, to add anything, to improve anything,” Kozhevnikov wrote. “Nature must be left alone, and we may observe the result.”

The aim of the first zapovednik was to protect the Barguzin sable, an animal with fur so dense, dark, and luxurious (nickname: "soft gold”) that tsars from Ivan the Terrible to Catherine the Great had worried for its future. Tsar Nicholas II himself was an avid hunter. But by 1917 he felt impelled to act: the carnivorous mammals with the lucrative pelts were facing extinction.

So, as it turned out, was Nicholas himself. By March of that same year he was forced to abdicate his throne, and in 1918 the Bolshevik revolutionaries executed him, along with the rest of the Romanov family. The seven decades of Soviet history that followed were marked by hardship and war—the Germans invaded in 1941; the Russians ultimately defeated them at a cost of millions of lives—and after that, by rapid industrial development and an arms race with America.

More than a quarter century after the fall of the Soviet Union, says Sergey Donskoy, Russia’s current minister of natural resources and the environment, the Russian landscape remains marred by “ecologically unfavorable territories with a high pollution level and degradation of natural systems.” That’s putting it mildly. When outsiders think of Russian environmental history, they’re less likely to think of nature reserves than of some of the biggest ecological disasters of the past century. Russia was the dominant force of the Soviet Union, which allowed the draining of the Aral Sea, once one of the world’s largest bodies of freshwater in Uzbekistand and Kazakhstan, or the explosion at Chernobyl in Ukraine, the world’s worst nuclear accident.

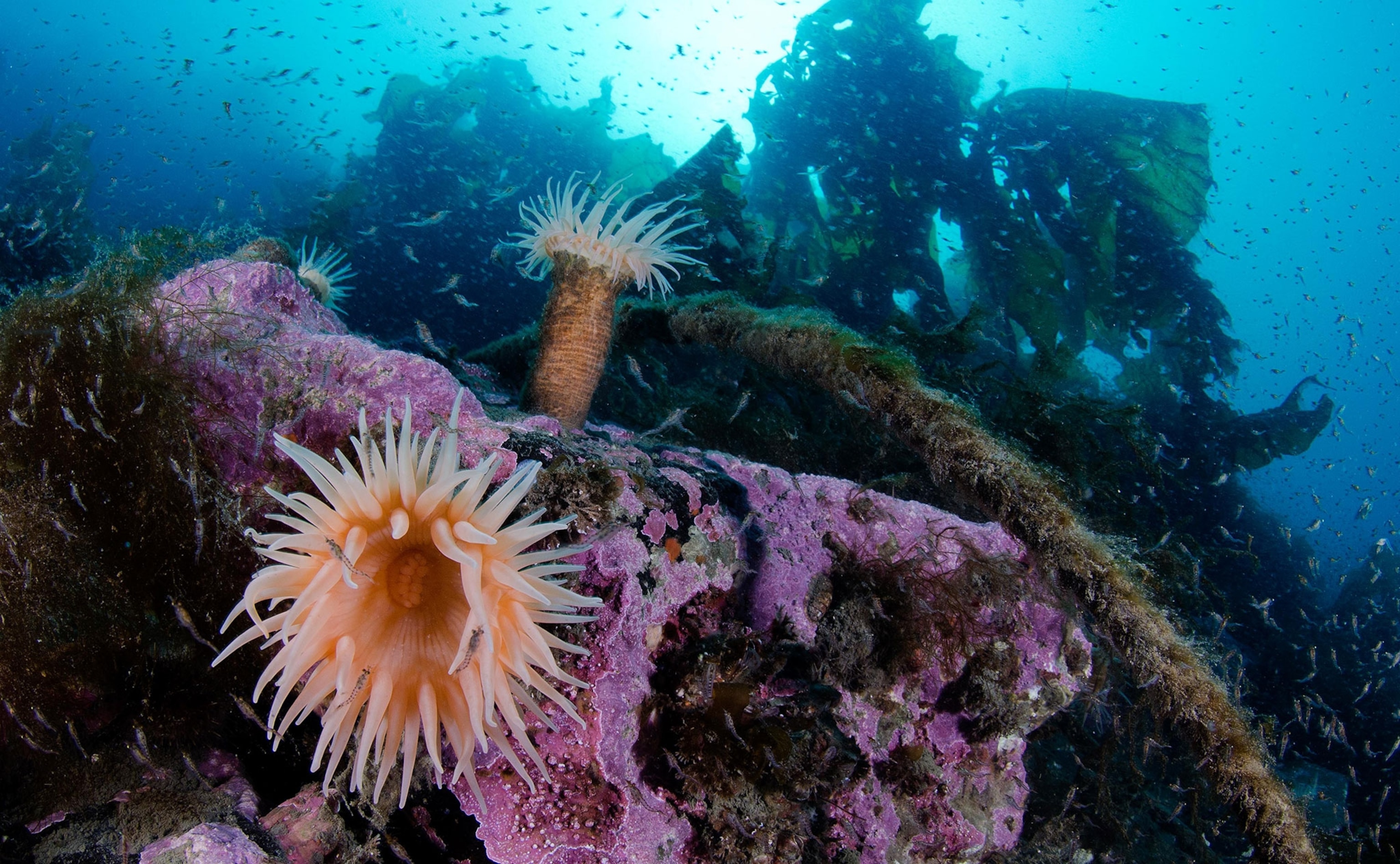

And yet the Barguzin sable didn’t go extinct. Nor did the Baikal seal, brown bear, and forest reindeer that call that same region home. They were saved by Nicholas’s creation, the Barguzinsky zapovednik. And today there are 102 more reserves like it.

Too Strict to Visit

Russian zapovedniks—from the Russian word meaning “commandment”—are some of the most highly protected areas in the world. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, they belong to its highest protection category: 1a, “…where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited.” U.S. National Parks, in contrast, combining as they do both conservation and public recreation, fall under lower IUCN categories.

In the 1980s Russia also began to create national parks that allow citizens access for recreation and educational programs. Today the country has 50 national parks, 59 federal refuges, and 17 federal natural monuments, all of which provide different levels of protection. But none are as strict as the zapovedniks.

Donskoy says that while the system of protected areas is a century old, “it really began to advance during the post-Soviet period.” Since 1992, he says, the number of federally protected areas “has grown by 95 percent—it’s almost doubled.”

Today that system faces a big challenge: Few Russians understand how to publicly support, enjoy, or help safeguard it—because they’ve traditionally been excluded from it.

Whereas in American parks the goal is “conservation plus recreation,” says Igor Chestin, CEO of the World Wide Fund for Nature Russia, “in Russia it is conservation plus science. These zapovedniks were originally established as field labs with limited access, if any, for private visitors.”

Even today a special permit is typically required to visit a zapovednik. Few people do.

Chestin says that in polls about what makes Russians most proud of their nation, most say it’s the country’s natural wealth. Russians know their nature is impressive, but few feel involved, he says.

“We’re all proud of our nature,” he says, “but only one percent of us actually does anything for nature” through volunteerism or other efforts.

Learning to Love Parks

One aim of the Year of Ecology and Protected Areas is to change that. The Russian government would like to increase public visitation of its National Parks, which are already more accessible than the zapovedniks. Vsevolod Stepanitsky of the environment ministry is an admirer of the U.S. National Park Service.

“In my opinion,” he says, “it has managed to achieve something that either doesn’t exist or is not developed enough in the Russian National Parks system.” That includes, he says, “an extremely high level of support for the national-parks idea, both from the general public and from public authorities of different levels. A balance between biodiversity and landscape protection and recreation and ecological tourism development. And a vast and effective ranger service with extensive ‘policing’ rights and responsibilities.” The WWF, for its part, is fighting recent changes in Russian law that it says would weaken protection of the zapovedniks, even allowing hotels and ski trails to be built in some of them. But it is also launching a campaign, provisionally called “1% of Russians”, that enlists celebrities to raise public interest and involvement in protected areas in general.

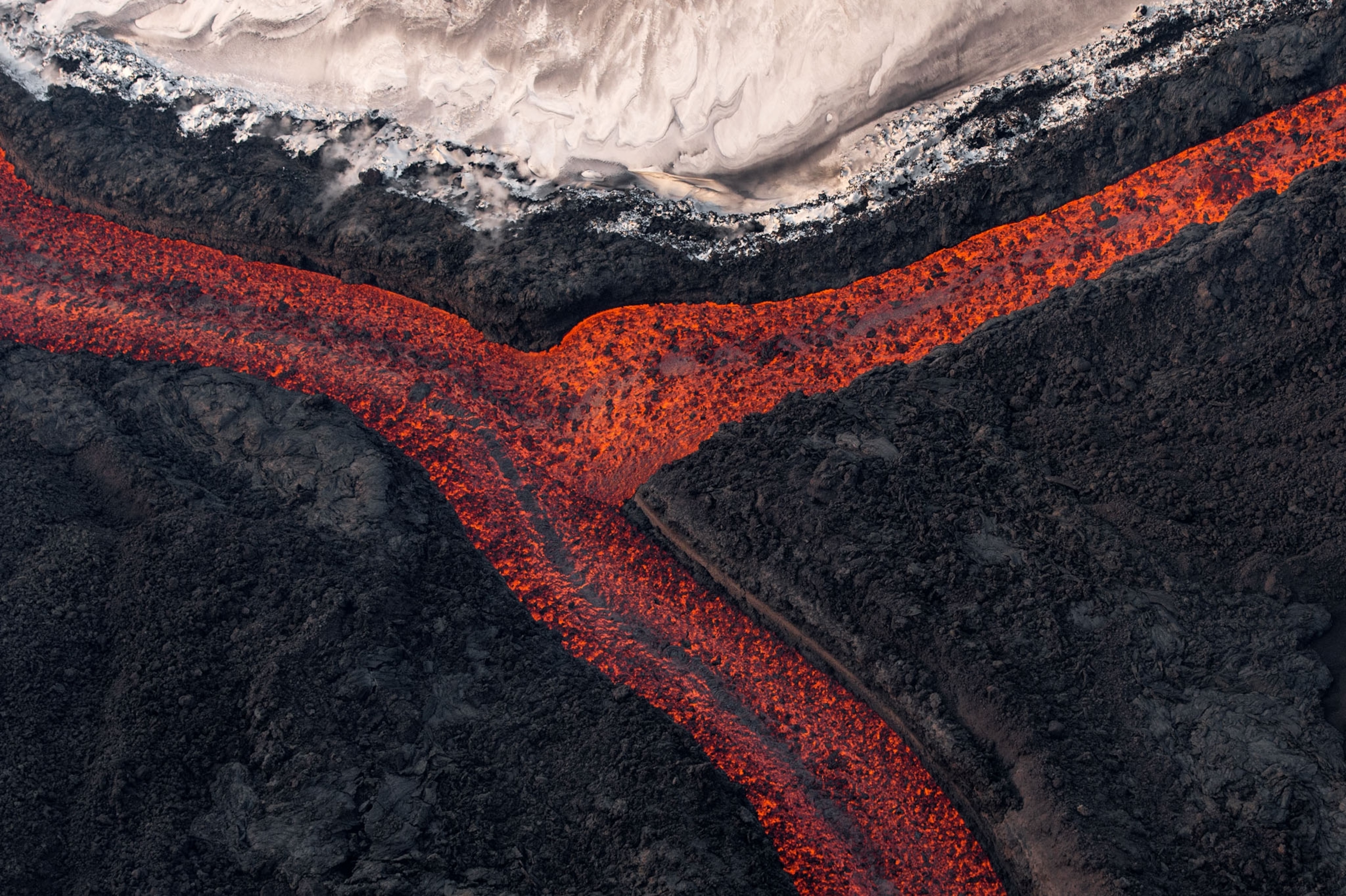

The government says it wants to expand the system. Stepanitsky says that by 2020, Russia is planning no fewer than 18 new federally protected areas, including at least five new zapovedniks, at least 11 national parks, and two federal refuges as well as the expansion of previously protected areas. One new national park and a zapovednik will be established in the Arctic, he says. This past August, on the same day that U.S. President Barack Obama announced a massive expansion of national marine monument in the Hawaiian Islands, the Russian government enlarged the existing Russian Arctic National Park to include the icy, biodiverse islands of Franz Josef Land.

“It’s the northernmost archipelago in the world and home to walruses, polar bears, and bowhead whales,” says National Geographic’s Pristine Seas founder and explorer-in-residence Enric Sala. “It’s a historically magical place only discovered in the late 1800s.” (Read more about the exploration of Franz Josef Land.)

Another example of Russian leadership on environmental matters, Sala says, was the recent protection of the Ross Sea in Antarctica, on which Russia collaborated with the U.S., the European Union, and other countries. All that makes him hopeful for this centenary year of the first zapovednik—hopeful that Russians will keep working to preserve “some of the most extraordinary places on our planet,” the ones in their own immense country.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Can Florida save this tiny gecko before its too late?Can Florida save this tiny gecko before its too late?

- Elephants may call each other by name, a rare trait in natureElephants may call each other by name, a rare trait in nature

- Are 'giant, flying' joro spiders really taking over the U.S.?Are 'giant, flying' joro spiders really taking over the U.S.?

- This invisible killer takes out 3.5 billion U.S. birds a yearThis invisible killer takes out 3.5 billion U.S. birds a year

- Charlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a diseaseCharlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a disease

- See how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summerSee how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summer

Environment

- These photos show what happens to coral reefs in a warming worldThese photos show what happens to coral reefs in a warming world

- How scientists link specific weather events and climate changeHow scientists link specific weather events and climate change

- Extreme heat is ahead—and you’ll feel every degree of itExtreme heat is ahead—and you’ll feel every degree of it

- Ready to give up fast fashion? Give 'slow fashion' a try.Ready to give up fast fashion? Give 'slow fashion' a try.

- Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry

- Paid Content

Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry

History & Culture

- These forgotten female veterans are finally getting their dueThese forgotten female veterans are finally getting their due

- How did the Maya choose sacrifice victims? DNA yields new clues.How did the Maya choose sacrifice victims? DNA yields new clues.

- He was a Founding Father. His son sided with the British.He was a Founding Father. His son sided with the British.

- How the rainbow flag became a symbol of the LGBTQIA+ communityHow the rainbow flag became a symbol of the LGBTQIA+ community

- No women allowed: These 5 destinations are men-onlyNo women allowed: These 5 destinations are men-only

Science

- Scientists are making advancements in birth control—for menScientists are making advancements in birth control—for men

- This is the biggest health challenge women face in their 50sThis is the biggest health challenge women face in their 50s

- How scientists link specific weather events and climate changeHow scientists link specific weather events and climate change

- Why health advocates are concerned about a chemical in your decafWhy health advocates are concerned about a chemical in your decaf

Travel

- The Chicago River was a toxic wasteland. Now it's an urban oasis.The Chicago River was a toxic wasteland. Now it's an urban oasis.

- Going off-grid in south-central Colorado’s San Luis Valley

- Paid Content

Going off-grid in south-central Colorado’s San Luis Valley - The 10 best hotels in Maine for every kind of traveler

- Travel

- Destination Guide

The 10 best hotels in Maine for every kind of traveler - 10 incredible family adventures to try in Maine

- Travel

- Destination Guide

10 incredible family adventures to try in Maine - Why you should visit this scenic Vermont town

- Paid Content

Why you should visit this scenic Vermont town