UNLIMITED

Thelma & Louise: The film that gave women firepower, desire and complex inner lives

Screenplay idea: two women go on a crime spree.” Callie Khouri was working as a production assistant for a firm in Los Angeles making ads and pop videos when she wrote this memo to herself in 1987. It was a germ of an idea, but a potent one: giving two women the kind of rule-breaking, all-action lead roles Hollywood regularly handed out to men. “They're leaving town, both leaving behind their jobs and families,” she continued. “They kill a guy, rob a store, get hooked up with a young guy.” As Khouri fleshed out the idea, she wrote her screenplay out by hand at home, and typed it up at work. Four years later it had been directed by Ridley Scott on a multimillion-dollar budget, with Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis in the lead roles.

Thelma & Louise became one of the most talked-about films of 1991 and Khouri walked away with an Oscar, a Bafta and a Golden Globe. Back then, many people thought that Hollywood would be changed forever, that we were entering a new era of gender equality on screen; others felt that the movie represented “toxic feminism” with “an explicit fascist theme”. In the intervening years it has become ever more beloved, and you even sense its legacy in this year’s big Oscar hits: the free-spirited women of Nomadland, and the vengeful outsider of Promising Young Woman. But still, in the wake of #MeToo, and with gender inequality rife in the industry, Hollywood’s true Thelma & Louise moment is yet to come.

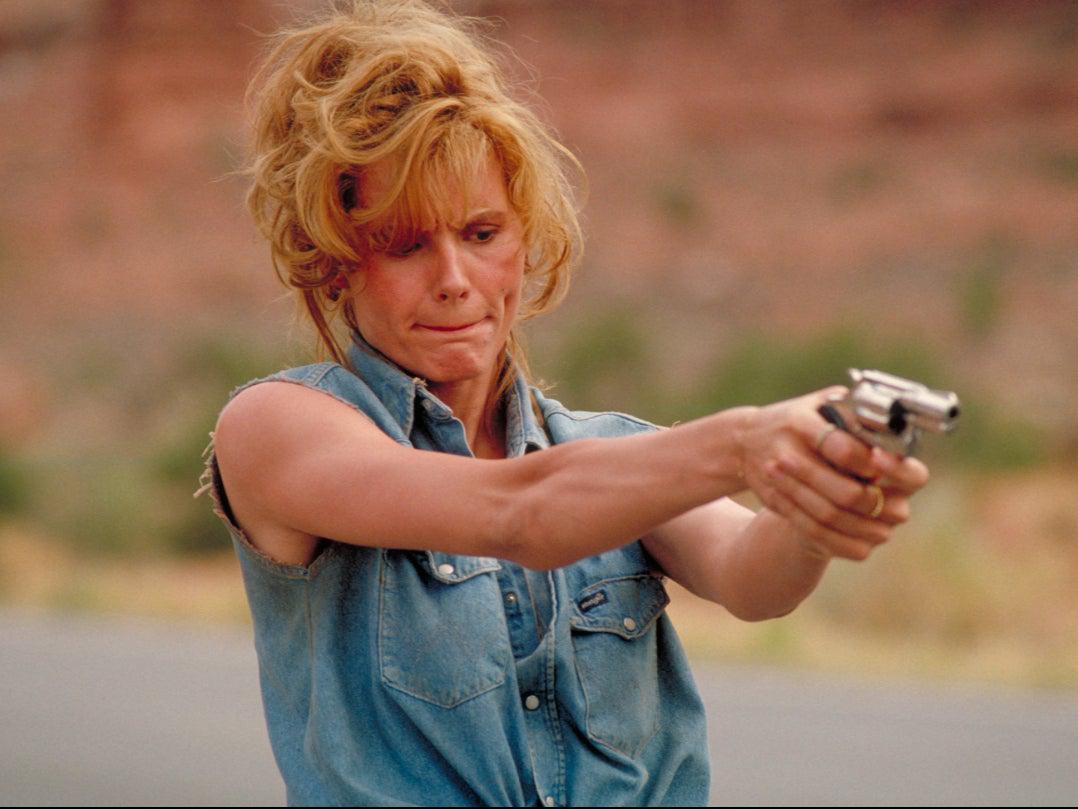

That phrase, a “Thelma and Louise” moment, has entered the language as a feminist awakening linked to a point of no return – the movie in a nutshell. The plot of Thelma & Louise begins with an early shock and barrels forward to one of the most famous endings in movie history. It’s the story of two working-class women from Arkansas heading to the hills for a weekend of freedom. When they stop at a bar en route, Thelma (Davis) is sexually assaulted and Louise (Sarandon) shoots her friend’s would-be rapist in the chest. From that point on the women are fugitives, aware that the police won’t accept their self-defence story, that they can’t go home, they can only keep going – to Mexico, or wherever the road may take them. Along the way, Thelma has a transformative one-night stand with a young man played with overt eroticism by Brad Pitt, and the two women take stabs at revenge on the macho culture that circles them: locking a State Trooper in the boot of his car, exploding the oil truck of a sleazy roadhog. “I don’t remember ever feeling this awake,” says Thelma, before the two women decide to take their fate into their own hands.

“Thelma & Louise is a turning point, I think in terms of the representation of women,” says Dr Shelley Cobb, associate professor of film at the University of Southampton. “There's a particular shift in the early 1990s that Thelma & Louise hits. We were moving out of the feminist backlash of the Eighties, and into third-wave feminism, post-feminism. We’re moving into that period where you have the return of a new kind of strong female character, with Thelma & Louise or Terminator 2.” As the film opens, Thelma is an unhappy housewife with a babyish, boorish husband who is clearly cheating on her. Louise is working as a diner waitress, stuck in a relationship that is slowly drifting nowhere. But for two hours, these women become Butch and Sundance, and even more. Khouri’s screenplay transforms them into the stars of a road movie, a Western, a Bonnie and Clyde-style thriller, and even a screwball comedy. No man comes to their rescue. Instead, Louise picks up a gun, and throws away her lipstick. And put-upon, girlish Thelma grows in courage, to take on Louise’s role as protector when it’s really needed.

The wilful mix of genres in Thelma & Louise offers a crowd-pleasing blend of action and humour – and the original trailer wildly overplayed the latter, showcasing the movie as a sexy, screwy romp, with lashings of line-dancing, topless Pitt and one-liners: “We’ll be drinking margaritas by the sea, mamacita!” For feminist film historian Dr Maggie Hennefeld of the University of Minnesota, the film’s humour is one of its key strengths: “Thelma & Louise draws on both the more conservative tendencies of the romantic-comedy genre and the incisive absurdity of dark humour,” says Hennefeld. “Even their outbreaks of retributive feminist violence provoke laughter: they’re abrupt, surprising, and reveal the absurdity of the world that keeps putting female characters in the most awful, impossible situations.” Case in point, the sputtering outrage of the truck driver when his tanker explodes, or Louise’s dry explanation to the State Trooper she has just incapacitated: “My husband wasn't sweet to me. Look how I turned out.”

Director Ridley Scott has a key role in how we talk about the representation of women on screen. In Alison Bechdel’s famous 1985 cartoon, Alien is the only movie that her protagonist has been able to see in years, the one movie to pass her strict test: the film has to have at least two women in it, who talk to each other about “something besides a man”. Thelma & Louise cemented Scott’s reputation as a Hollywood heavyweight who could grapple with feminist themes. You can see his touch in the film’s visual splendour, including those endless desert landscapes and the “army” that surrounds our heroines in the finale. The look of the film is playful too – just look at the way Pitt is introduced playing with a hose. But we should be wary of taking credit away from screenwriter Khouri. “I see it as a Callie Khouri film, especially when you put it alongside the other things she's written and done,” says Cobb. “Everything from the way they blow up the truck to the idea that Brad Pitt is a figure to be looked at and mimicked, to the idea that a one-night stand for a woman can be an OK thing – the script is so important.”

Khouri went on to direct female-led films including Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, and more recently, to create the hit TV series Nashville. Davis has called Khouri a “revolutionary”, because “she creates characters that are in charge of their own fate to the bitter end. Female characters who are in charge of themselves.” And there’s more to Thelma & Louise than the action and the laughs. It’s also a deeply challenging film about rape culture, something that many of the interviewees in Jennifer Townsend’s insightful 2017 documentary Catching Sight of Thelma & Louise dwell on. Townsend revisits men and women who filled in a research questionnaire about the film on its original release. One woman recalls her own marriage, and states: “There are a lot more Thelmas out there than many people imagine.” Another, Christi, weeps as she says that rape culture has not changed since 1991.

In the film’s brutal attempted rape scene, Louise interrupts the attack on Thelma. She doesn’t shoot the assailant in the act, though, she shoots him after he shows no remorse for his crime. The incident that criminalises Louise is arguably not the attack in the car park, but a nameless something that happened to her a few years before the film begins, in Texas. It’s never quite explained, although Thelma tries to guess, but whatever it was is so terrible that the fugitives divert their journey to Mexico, to avoid the second largest state in the US, because she can never return.

For Cobb, the writing of Louise’s Texas experience is what brings the film to another level. “It creates the road genre for them, because that's the reason they end up on the road for so long, because they can't go through Texas. That's what makes them outlaws.” And she praises the screenplay for not spelling it out – giving the audience room to imagine what could be so traumatic as to put an entire state off-limits. Sarandon has said that the Texas angle seemed to pass many people by on the film’s first release. “When it came out, actually, people kind of missed the rape,” she said last year. “Now you look at it and you’re hip to what she’s talking about, and that she’s having this flashback of being assaulted. But I remember having to clarify that.”

Khouri was the only person to win an Oscar for Thelma & Louise, though both leads and Scott were also nominated. The film that swept the board at the Oscars that year was The Silence of the Lambs, another film in which a female lead confronts male violence. That film’s star, Jodie Foster, was one of the first actors attached to the film, alongside Michelle Pfeiffer. Goldie Hawn and Meryl Streep also nearly jumped in the Thunderbird together – instead they made Death Becomes Her.

Put that way, it seems like the early 1990s was shaping up to be a boom time for female creatives in Hollywood. But never underestimate the power of a backlash. There were those, including journalist John Leo of the “toxic feminism” take in Time magazine, who took exception to Thelma & Louise: those who saw the film as gratuitously violent (despite the fact that the film’s body count stands at just one), and the men as unrealistic caricatures. It’s barely worth pointing out the avalanche of Hollywood action movies in which men are excessively violent, and the supporting female characters are barely sketched in at all. Khouri’s screenplay isn’t about playing with guns but resisting oppression. “I'll take store-robbing, rape-avenging, truck-exploding ‘toxic feminism’ over neoliberal, ‘lean-in’, fake feminism any day,” says Hennefeld. “Fighting the patriarchy means throwing some elbows.”

When Thelma & Louise make the decision to jump, it’s a condemnation of contemporary America, and especially the establishment forces of law and order who offer them no protection – a theme in the film that resonates even more powerfully in 2021. “They have already been let down by and left out of the American dream,” says Cobb. “They go on the road to have a holiday from their normal lives, but the patriarchy is wherever they go, and their lack of middle-class femininity will only make their confrontation with the police – the ultimate symbol of institutional authority – worse. They have no way out.”

Davis had this to say to the detractors: “If you’re threatened by this movie, you're identifying with the wrong person.” Which makes a powerful point about on-screen representation: some audiences are so used to men playing the lead that they identify with them even when that isn’t the case. Or to put it more bluntly: sexists can’t get their heads around this movie. Davis has been fighting for better roles for women in mainstream cinema ever since she played Thelma. She said recently that Thelma & Louise “changed forever how I considered what parts to play. I would think: ‘What are the women in the audience going to say when they see this movie?’” In 2004 she founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, an organisation whose aim is to improve female representation in film and television. And she has been outspoken about demanding change in the industry – a change that hasn’t happened yet. “I believed all the press reaction about Thelma & Louise, that it was going to change everything and that there were now going to be far more female lead characters in movies, and I was thrilled,” she has said. “There have been a number of times that movies have come out and people [have said], ‘This is going to change things,’ and it didn’t.”

Thelma & Louise isn’t a movie that encourages looking back, but the 30th anniversary of this film is a good enough reason to cheer for a film that smuggles feminist critique into a collection of Hollywood genres. A film about a feminist awakening, which gave women lead roles with firepower, desire and complex inner lives. Thelma & Louise is not a truly radical feminist film, but it does create space for a new kind of commercial movie that pushes the boundaries further. Films in which women don’t have to die seconds after they kiss each other, films in which survivors can be free of their trauma, films in which women are in charge of their own fate to the bitter end.

“What I love, most of all,” says Hennefeld, “is what it's come to mean to female audiences over the years. It sparks the imagination toward demanding a different kind of world.” And sometimes you have to follow the road wherever it leads you, even if it takes you into the unknown.