UNLIMITED

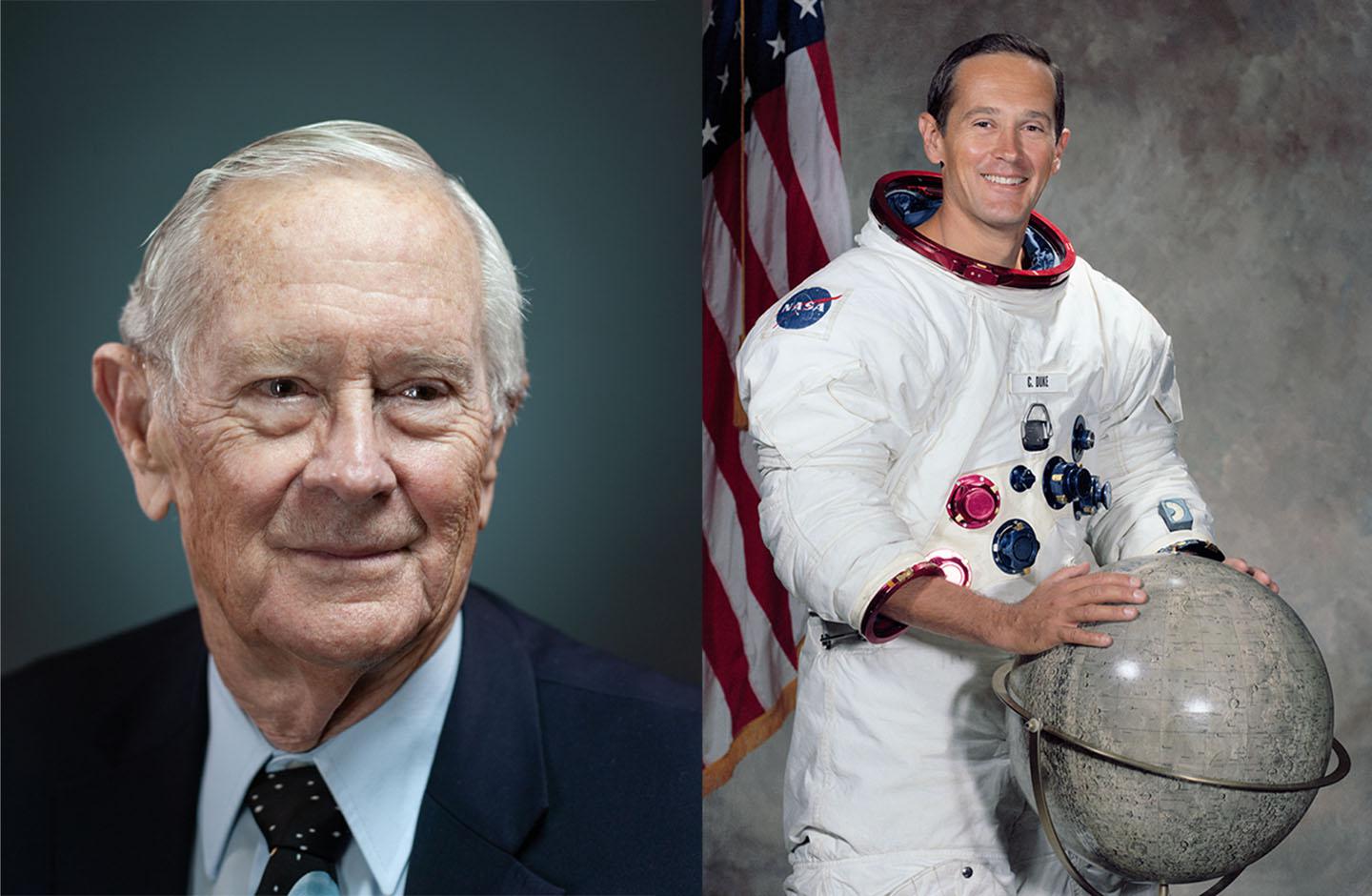

Apollo Astronauts Reflect on JFK's Challenge and the Future of Space Travel

They traveled around 238,000 miles from home—the farthest human beings have ever traveled before or since. Their crafts contained less technology than schoolchildren today hold in their hands with their iPhone. The astronauts relied on a primitive computer that operated at 1.024 Megaherz and a control room in Houston filled with men (mostly) working mostly the old fashioned way—lots of human brains, pencil and paper. Today, orbital trajectories are calculated in seconds by supercomputers operating hundreds of millions of times faster than NASA's 1969 model.

Fifty years have passed since Neil Armstrong was the first to walk on the moon on July 20, 1969. Armstrong is among only 24 men who have flown there; only 11 other joined Armstrong's small fraternity.

As their feat recedes into history, the men of the Apollo program take their place among the pantheon of the great explorers of human history. Marco Polo. Christopher Columbus. Their courage and curiosity are rightly celebrated. Their children and grandchildren now look at the archaic flying machines that took them to the moon and back—the same way they look at 15th Century mariners in wooden boats powered by wind, who traveled through storms to discover unmapped continents.

The trip to the moon changed the astronauts in ways they couldn't predict. They were the first humans to see their blue planet, Earth, rising behind the lifeless orb of the moon—and to bring back with them a measured sense of its relative smallness and fragility. During the hours and days the Apollo astronauts were in lunar orbit on voyages between 1968 and 1972, the Vietnam War was raging, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in an arms race with the most powerful weapons mankind had ever invented, and American cities were tense with anti-war protests and racial unrest. The space program itself was a Cold War enterprise, a race to beat the Soviets to the moon.

The lunar endeavor, though, transcended jingoism and national borders. When the first moon landers returned to Earth they were greeted with ticker tape parades and global outpourings of admiration in 24 cities on the GIANTSTEP Apollo 11 Presidential Goodwill Tour. (Though, Moscow was not one of the 24 cities).

The last moon landing was on December 11, 1972. Even then, attention had drifted away from the miracle of it, and only true space buffs can recite the names of the last men to walk on the moon—Harrison Schmitt and Eugene Cernan. By then, the Watergate scandal that would bring down President Nixon was unravelling. The Vietnam War was de-escalating, with America headed for a devastating loss. The decline of American exceptionalism was, perhaps, already beginning.

The fiftieth anniversary of the first human moon-landing

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days