Robert Zellinger de Balkany, who died last September at 84, lived large. That much was clear last weekend in Paris, when I toured his house, Hôtel de Feuquières, a 1730s mansion at 62 rue de Varenne, as part of a Sotheby’s estate-auction preview. The Romanian-born shopping-center magnate, property developer, royal in-law, polo patron, and collector packed his brightly gilded rooms with staggering 17th-century clocks, Louis XV furniture, Russian and German silver and vermeil, plush Aubusson carpets, and paintings by Van Dyck and Stubbs. One hundred and thirty-two lots, beginning with a circa-1650 vermeil-covered tankard by Dietrich Thor Moye (estimate $7,865–$11,235) and ending with an Empire flame-mahogany commode and matching secrétaire à abattant ($50,558–$67,410), go on the block at Sotheby’s Paris on September 20. One piece I could kill for is a completely mad Directoire gilt-bronze mantel clock ($33,705–$56,175), attributed to Pierre-Etienne Romain and ornamented with a dozen lightning bolts shooting out of a churning gold storm cloud; a nearly identical model is at the Élysées Palace.

Hôtel de Feuquières, which had been the entrepreneur’s city residence since 1969—the year he wed Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, a daughter of Italy’s last king—doesn’t offer much of a takeaway for the average homeowner, though the reception rooms’ audacious palettes are electrifying. Color is finally back in style, you know, so even though Zellinger de Balkany’s schemes appear brash—he was a swashbuckling figure with a polarizing reputation—they are à la mode.

“A subtle mix” is how Sotheby’s describes the furnishings of the yellow-and-white salon, cherry-red salon, and pine-green salle à manger, though the effect is anything but discreet. Restored and refreshed between 2011 and 2014, by Zellinger de Balkany himself—Italian decorator Federico Forquet offered advice on the fabrics—the side-by-side rooms are flamboyant settings perfect for coutured guests gossiping amid candlelight and the regal treasures that the man of the house had been acquiring since his new-money youth. Paired objects predominate, with fireplaces flanked by busts on pedestals, then by inlaid cabinets with clocks, and those, in turn, flanked by matched candelabras. Some of the antiques, though, have been so extravagantly rehabilitated that they look utterly brand-new. Gesturing to one gleaming meuble, a gentleman on the tour whispered to his companion, “Of course it’s real—but it also could be fake.”

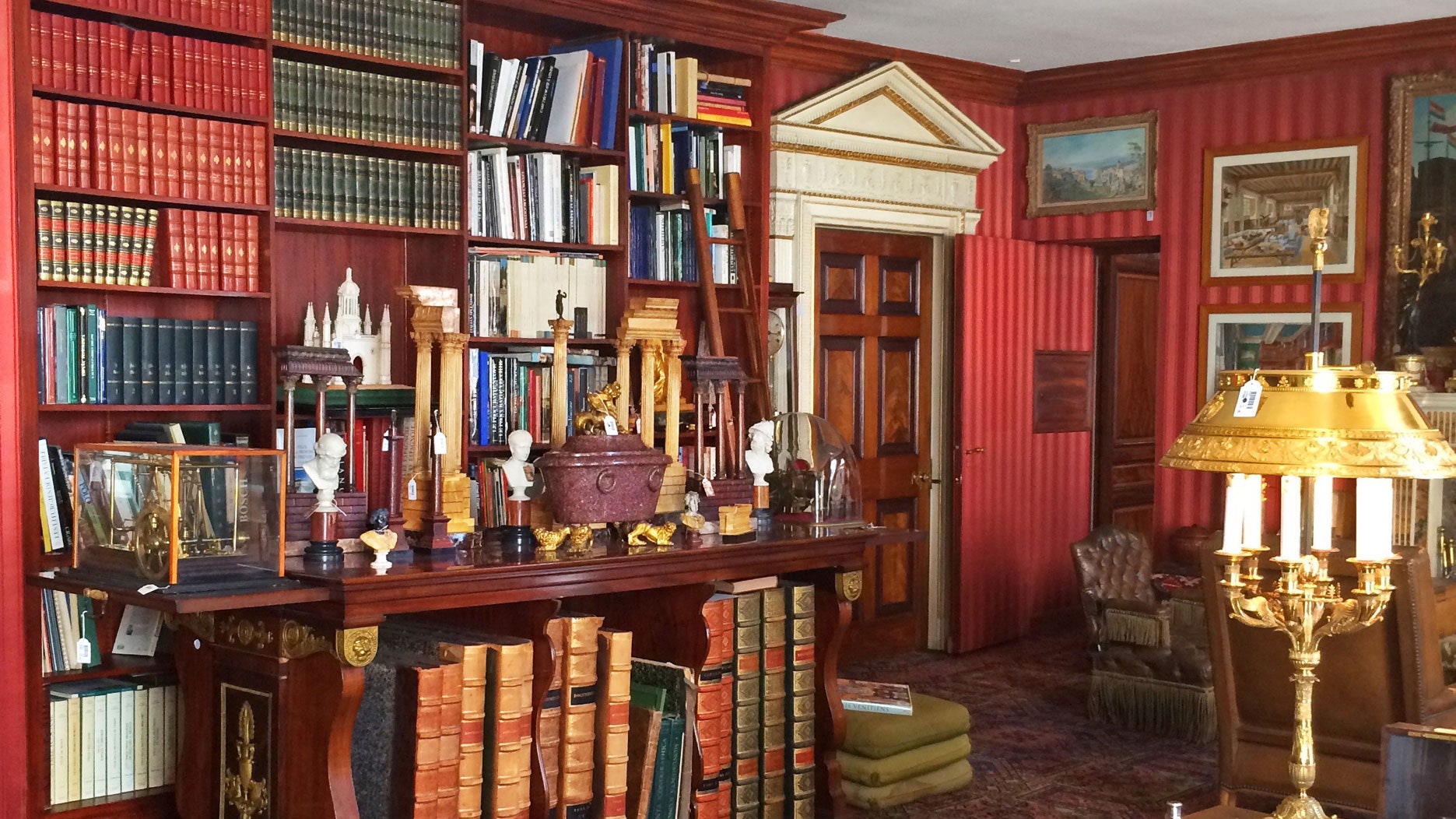

Zellinger de Balkany’s personal style—call it swaggering elegance or ham-fisted glamour, because either works—was obviously informed by 18th-century Bourbon monarchs as well as France’s multinational connoisseurs of the 20th century, particularly Mexican mining heir Carlos de Beistegui, the arch-aesthete laird of Château de Groussay. The iconic Louis XV–style dining chairs from Beistegui’s Paris mansion are apparently the same ones (the set of 18 is expected to bring $16,853 to $28,088) that stand in Hôtel de Feuquières’s dining room, and the door cases in the third-floor library recall similar architectural elements at Groussay. And like Beistegui, Zellinger de Balkany would commission Russian artist Alexandre Serebriakoff to record his personal interiors in crystalline watercolors.

The third floor’s private rooms, where Zellinger de Balkany slept, read, and relaxed, are far less flashy. (Ditto the reception floor’s soulful smoking room, a densely furnished Proustian space that was decorated by Jacques Garcia.) Low-ceilinged and homey, this area was handled in the 1980s by Henri Samuel, one of history’s most sensitive tastemakers, and his layered, seductive installations have aged beautifully, with all the humanizing dents and dings—parched leather, faded lampshades—that the reception rooms lack. The first floor and the third floor were decorated for different purposes, of course, with the former meant to impress and the latter intended to be lived in.

Silk Road–style fabrics and carpeting romantically clash in Samuel’s hands, and a bedroom stretched with an airy flowered fabric is complemented by woodwork painted in matching pastel tones. Baths have a country-house feel: simple and masculine, with tubs set into wood surrounds. The large multipurpose master bedroom, though, possesses a bit of the reception floor’s pomp, furnished with an impressive suite of Empire ormolu-mounted flame-mahogany furniture and a boxed-in tub surmounted by a vast artwork depicting 1795’s Battle of Hyères Islands. Given that Réalités once described Zellinger de Balkany as “the Napoléon of real estate,” knowing that he slumbered in an unapologetically imperial chamber seems entirely appropriate.