apple stories

A disability advocate preserves his voice with iPhone

For physician and disability advocate Tristram Ingham, Apple’s new speech accessibility features provide reassurance amid an uncertain future

When introducing himself, Tristram Ingham often begins with a te reo Māori greeting before breaking into English. The New Zealand-native has a voice that’s kind, soft, and sure, with every word carefully chosen and placed. As a physician, academic researcher, and disability community leader, Ingham’s words are his power.

Ingham has facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), which causes progressive muscle degeneration starting in the face, shoulders, and arms, and can ultimately lead to the inability to speak, feed oneself, or in some cases, blink the eyes. In 2013, he began using a wheelchair, and in recent years he has noticed changes in his voice.

“I find that by the end of a long day, just bringing up my voice gets a bit harder,” he says, recounting a recent, frustrating incident: “I had to give a conference presentation just last month, and it turned out that, on the day, I wasn’t able to deliver it because of my breathing. So I had to get someone else to present for me, even though I had written it.”

In the future, it is possible Ingham may not be able to use his speaking voice at all. “I’m very aware on a professional level that using my voice is getting harder. I am aware that when I get more fatigued, I get quieter, harder to understand,” he says, noting the cognitive dissonance of a progressive condition. “But on a human level, I put that out of my mind, because what can one do about it?”

Tristram Ingham narrates Apple’s “The Lost Voice,” created for International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

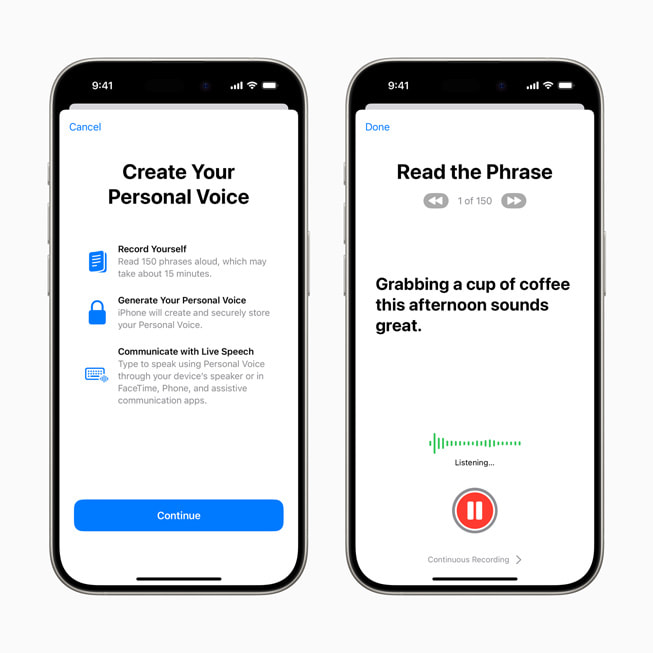

This fall, Apple launched its new Personal Voice feature, available with iOS 17, iPadOS 17, and macOS Sonoma. With Personal Voice, users at risk of speech loss can create a voice that sounds like them by following a series of text prompts to capture 15 minutes of audio. Apple has long been at the forefront of neural text-to-speech technology. With Personal Voice, Apple is able to train neural networks entirely on-device to advance speech accessibility while protecting users’ privacy.

“Disability communities are very mindful of proxy voices speaking on our behalf,” Ingham says. “Historically, providers have spoken for disabled people, family have spoken for disabled people. If technology can allow a voice to be preserved and maintained, that’s autonomy, that’s self-determination.”

Ingham created his Personal Voice for Apple’s “The Lost Voice,” in which he uses his iPhone to read aloud a new children’s book of the same name created for International Day of Persons with Disabilities. When he tried the feature for the first time, Ingham was surprised to find how easy it was to create, and how much it sounded like him.

“It was really straightforward, I was quite relieved,” he says, remarking on the voice coming from his iPhone: “I’m really pleased to hear it in my voice with my style of speaking, rather than an American voice, or an Australian voice or a U.K. voice.”

Live Speech, another speech accessibility feature Apple released this fall, offers users the option to type what they want to say and have the phrase spoken aloud, whether it is in their Personal Voice or in any built-in system voice. Users with physical, motor, and speech disabilities can communicate in the way that feels most natural and comfortable for them by combining Live Speech with features like Switch Control and AssistiveTouch, which offer alternatives to interacting with their device using physical touch.

“Technology can be critical for preserving one’s own natural-sounding voice,” says Blair Casey, executive director of the nonprofit Team Gleason. The organization supports individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), another progressive condition which causes speech loss in 1 of every 3 individuals diagnosed. “Our voices are part of our identity,” says Casey, “When diseases like ALS threaten to take away the ability to speak, tools like Personal Voice can help anyone continue to sound like their unique, authentic self.”

“At Apple, we design for everyone, and that includes individuals with disabilities,” says Sarah Herrlinger, Apple’s senior director of Global Accessibility Policy and Initiatives. “Communication is a crucial part of what makes us human, and we’re committed to supporting nonspeaking users as well as those who may be at risk of speech loss.”

For Ingham, Personal Voice is just one of many tools that allows him to keep doing what he loves.

“I’m not prepared to just sit at home,” Ingham says. “I work, I volunteer in the community, and I expect to contribute meaningfully. Technology helps me to do that.”

Ingham’s professional accomplishments include credit for originating the widely used epidemiological concept of the COVID bubble, which he first proposed as a way to protect people with disabilities and weakened immune systems early in the pandemic. He also serves as chairman of the national representative body for disabled Māori, and advises New Zealand’s Ministry of Health, which complements his work as a senior research fellow at the University of Otago, Wellington’s Department of Medicine.

Perhaps most important, though, is keeping a personal connection with friends and family, regardless of the state of his speaking voice.

“I’ve got three grandchildren,” he says. “I love to read them bedtime stories. They come and stay the night quite often, and they love stories about sea creatures, tsunamis, things like that. And I just want to be able to ensure that I can keep doing that into the future.”

“You never know what is going to happen,” he continues, “and when you have something that is so precious, a taonga — a treasure — I think we should do anything we can to make sure we keep hold of that.”

Share article

Media

-

Text of this article

-

Images in this article