Okurigana (送り仮名 accompanying letters) are kana suffixes following kanji stems in Japanese written words. They serve two purposes: to inflect adjectives and verbs, and to disambiguate kanji with multiple readings. For example, the non-past verb form 見る (miru, "see") inflects to past tense 見た (mita, "saw"), where 見 is the kanji stem, and る and た are okurigana, written in hiragana script. Okurigana are only used for kun'yomi (native Japanese readings), not for on'yomi (Chinese readings) – Chinese morphemes do not inflect in Japanese,[note 1] and their pronunciation is inferred from context, as many are used as parts of compound words (kango).

When used to inflect an adjective or verb, okurigana can indicate aspect (perfective versus imperfective), affirmative or negative meaning, or grammatical politeness, among many other functions. In modern usage, okurigana are almost invariably written with hiragana; katakana were also commonly used in the past.

Contents |

English analogs [link]

Analogous orthographic conventions find occasional use in English, which, being more familiar, help in understanding okurigana.

As an inflection example, when writing Xing for cross-ing, as in Ped Xing (pedestrian crossing), the -ing is a verb suffix, while cross is the dictionary form of the verb – in this case cross is the reading of the character X, while -ing is analogous to okurigana. By contrast, in the noun Xmas for Christmas, the character X is instead read as Christ – the suffixes serve as phonetic complements to indicate which reading to use.

Another common example is in ordinal and cardinal numbers – "1" is read as one, while "1st" is read as fir-st.

Note that word, morpheme (constituent part of word), and reading may be distinct: in "1", "one" is at once the word, the morpheme, and the reading, while in "1st", the word and the morpheme are "first", while the reading is fir, as the -st is written separately, and in "Xmas" the word is "Christmas" while the morphemes are Christ and -mas, and the reading "Christ" coincides with the first morpheme.

Inflection examples [link]

Adjectives in Japanese use okurigana to indicate aspect and affirmation-negation, with all adjectives using the same pattern of suffixes for each case. A simple example uses the character 高 (high) to express the four basic cases of a Japanese adjective. The root meaning of the word is expressed via the kanji (高, read taka and meaning "high" in each of these cases), but crucial information (aspect and negation) can only be understood by reading the okurigana following the kanji stem.

- 高い (takai)

- High (positive, imperfective), meaning "[It is] expensive" or "[It is] high"

- 高くない (takakunai)

- High (negative, imperfective), meaning "[It is] not expensive/high"

- 高かった (takakatta)

- High (positive, perfective), meaning "[It was] expensive/high"

- 高くなかった (takakunakatta)

- High (negative, perfective), meaning "[It was not] expensive/high"

Japanese verbs follow a similar pattern; the root meaning is generally expressed by using one or more kanji at the start of the word, with aspect, negation, grammatical politeness, and other language features expressed by following okurigana.

- 食べる (taberu)

- Eat (positive, imperfective, direct politeness), meaning "[I/you/etc.] eat"

- 食べない (tabenai)

- Eat (negative, imperfective, direct), meaning "[I/you/etc.] do not eat"

- 食べた (tabeta)

- Eat (positive, perfective, direct), meaning "[I/you/etc.] ate/have eaten"

- 食べなかった (tabenakatta)

- Eat (negative, perfective, direct), meaning "[I/you/etc.] did not eat/have not eaten"

Compare the direct polite verb forms to their distant forms, which follow a similar pattern, but whose meaning indicates more distance between the speaker and the listener:

- 食べます (tabemasu)

- Eat (positive, imperfective, distant politeness), meaning "[My group/your group] eats"

- 食べません (tabemasen)

- Eat (negative, imperfective, distant), meaning "[My group/your group] does not eat"

- 食べました (tabemashita)

- Eat (positive, perfective, distant), meaning "[My group/your group] ate/has eaten"

- 食べませんでした (tabemasen deshita)

- Eat (negative, perfective, distant), meaning "[My group/your group] did not eat/has not eaten"

Disambiguation of kanji [link]

Okurigana are also used as phonetic complements to disambiguate kanji that have multiple readings. Since kanji, especially the most common ones, can be used for words with many (usually similar) meanings — but different pronunciations — key okurigana placed after the kanji help the reader to know which meaning and reading were intended. Both individual kanji and multi-kanji words may have multiple readings, and okurigana are used in both cases.

Okurigana for disambiguation are a partial gloss, and are required: for example, in 下さる, the stem is 下さ (and does not vary under inflection), and is pronounced くださ (kudasa) – thus 下 corresponds to the reading くだ (kuda), followed by さ (sa), which is written here kuda-sa. Note the okurigana are not considered part of the reading; grammatically the verb is kudasa-ru (verb stem + inflectional suffix), but orthographically the stem itself is analyzed as kuda-sa (kanji reading + okurigana). Compare with furigana, which: specify the complete reading,[clarification needed] appear outside the line of the text, and which are omitted if understood.

Disambiguation examples include common verbs which use the characters 上 (up) and 下 (down):

- 上 (read a)

- 上がる (a-garu) "to ascend/to make ready/to complete", and 上げる (a-geru) "to raise, to give (upwards)"

- 上 (read nobo)

- 上る (nobo-ru) "to go up/to climb (a set of stairs)", and 上す (nobo-su) "serve food, raise a matter (uncommon)" [note 2]

- 下 (read kuda)

- 下さる (kuda-saru) "to give [to the speaker from a superior]", and 下る (kuda-ru) "to be handed down [intransitive]"

- 下 (read o)

- 下りる (o-riru) "to get off/to descend" and 下ろす (o-rosu) "to let off (transitive)"

- 下 (read sa)

- 下がる (sa-garu) "to dangle (intransitive)", and 下げる (sa-geru) "to hang, to lower (transitive)"

Observe that many Japanese verbs come in transitive/intransitive pairs, as illustrated above, and that a single kanji reading is shared between the two verbs, with sufficient okurigana written to reflect changed endings. The above okurigana are as short as possible, given this restriction – note for instance that のぼる (noboru) / のぼす (nobosu) are written as 上る / 上す, not as ×上ぼる or ×上ぼす, while あがる must be written as 上がる to share a kanji reading with 上げる.

Another example includes a common verb with different meanings based on the okurigana:

- 話す (hana-su)

- "to speak/to talk". Example: ちゃんと話す方がいい。(chanto hanasu hou ga ii), meaning "It's better if you speak correctly."

- 話し (hana-shi)

- noun form of the verb hanasu, "to speak". Example: 話し言葉と書き言葉 (hanashi kotoba to kaki kotoba), meaning "spoken words and written words".

- 話 (hanashi)

- noun, meaning "a story" or "a talk". Example: 話はいかが? (hanashi wa ikaga?), meaning "How about a story?"

Okurigana are not always sufficient to specify the reading. For example, 怒る (to become angry) can be read as いかる (ika-ru) or おこる (oko-ru) – ×怒かる and ×怒こる are not used[note 3] – 開く (to open) may be read either as あく (a-ku) or as ひらく (hira-ku) – ×開らく is not used – and 止める may be read either as とめる (to-meru) or as やめる (ya-meru) – ×止る is not used.[note 4] In such cases the reading must be deduced from context or via furigana.

Ambiguity may be introduced in inflection – even if okurigana specify the reading in the base (dictionary) form of a verb, the inflected form may obscure it. For example, 行く i-ku "go" and 行う okona-u "perform, carry out" are distinct in dictionary form, but in past ("perfective") form become 行った i-tta "went" and 行った okona-tta "performed, carried out" – which reading to use must be deduced from context or furigana.[note 5]

Occasionally okurigana coincide with the phonetic (rebus) component of phono-semantic Chinese characters, which reflects that they fill the same role of phonetic complement. For example, in the word 割り算 (wa-ri-zan, division), the phonetic component of 割 is 刂, which is cognate to the okurigana り, which is derived from 利, which also uses 刂.

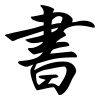

生 [link]

One of the most complex examples of okurigana is the kanji 生, pronounced shō or sei in borrowed Chinese vocabulary, which stands for several native Japanese words as well:

- 生 nama 'raw' or ki 'alive'

- 生う [生u] o-u 'expand'

- 生きる [生kiru] i-kiru 'live'

- 生かす [生kasu] i-kasu 'arrange'

- 生ける [生keru] i-keru 'live'

- 生む [生mu] u-mu 'produce'

- 生まれる or 生れる [生mareru or 生reru] u-mareru or uma-reru 'be born'

- 生える [生eru] ha-eru 'grow' (intransitive)

- 生やす [生yasu] ha-yasu 'grow' (transitive)

as well as the hybrid Chinese-Japanese word

- 生じる [生jiru] shō-jiru 'occur'

Note that some of these verbs share a kanji reading (i, u, and ha), and okurigana are conventionally picked to maximize these sharings.

Multi-character words [link]

Okurigana may also be used in multi-kanji words, where the okurigana specifies the pronunciation of the entire word, not simply the character that they follow; these distinguish multi-kanji native words from kango (borrowed Chinese words) with the same characters. Examples include nouns such as 気配り kikubari "care, consideration" versus 気配 kehai "indication, hint, sign" (note that the reading of 気 changes between kiku and ke, despite it not having an okurigana of its own), and verbs, such as 流行る hayaru "be popular, be fashionable", versus 流行 ryūkō "fashion". Note that in this later case, the native verb and the borrowed Chinese word with the same kanji have approximately the same meaning, but are pronounced differently.

Okurigana can also occur in the middle of a compound, such as 落ち葉 ochiba "fallen leaves" and 落葉 rakuyō "fallen leaves, defoliation" – note that the reading of the terminal 葉 changes between ba and yō despite it occurring after the okurigana.

Informal rules [link]

Verbs [link]

The okurigana for group I verbs (五段動詞 godan dōshi, also known as u-verbs) usually begin with the final mora of the dictionary form of the verb.

- 飲む no-mu to drink, 頂く itada-ku to receive, 養う yashina-u to cultivate, 練る ne-ru to twist.

For group II verbs (一段動詞 ichidan dōshi, also known as ru-verbs) the okurigana begin at the mora preceding the last, unless the word is only two morae long.

- 妨げる samata-geru to prevent, 食べる ta-beru to eat, 占める shi-meru to comprise, 寝る ne-ru to sleep, 着る ki-ru to wear

If the verb has different variations, such as transitive and intransitive forms, then the different morae are written in kana, while the common part constitutes a single common kanji reading for all related words.

- 閉める shi-meru to close (transitive), 閉まる shi-maru to close (intransitive) – in both cases the reading of 閉 is shi – 落ちる o-chiru to fall, 落とす o-tosu to drop – in both cases the reading of 落 is o.

In other cases (different verbs with similar meanings, but which are not strictly variants of each other), the kanji will have different readings, and the okurigana thus also indicate which reading to use.

- 脅かす obiya-kasu to threaten (mentally), 脅す odo-su to threaten (physically)

Adjectives [link]

Most adjectives ending in -i (true adjectives) have okurigana starting from the -i.

- 安い yasu-i, 高い taka-i, 赤い aka-i

Okurigana starts from shi for adjectives ending in -shii.

- 楽しい tano-shii, 著しい ichijiru-shii, 貧しい mazu-shii

Exceptions occur when the adjective also has a related verbal form. In this case, as with related verbs (above), the reading of the character is kept constant, and the okurigana are exactly the morae that differ.

- 暖める atata-meru (verb), 暖かい atata-kai (adjective) – in both cases 暖 is read atata – 頼む tano-mu, 頼もしい tano-moshii – in both cases 頼 is read tano

As with verbs, okurigana is also used to distinguish between readings (unrelated adjectives with the same kanji), in which case the okurigana indicate which reading to use.

- 細い hoso-i, 細かい koma-kai, 大いに oo-ini, 大きい oo-kii

Na-adjectives (adjectival verbs) that end in -ka have okurigana from the ka.

- 静か shizu-ka, 確か tashi-ka, 豊か yuta-ka, 愚か oro-ka

Adverbs [link]

The last mora of an adverb is usually written as okurigana.

- 既に sude-ni, 必ず kanara-zu, 少し suko-shi

Nouns [link]

Nouns do not normally have okurigana.

- 月 tsuki, 魚 sakana, 米 kome.

However, if the noun is derived from a verb or adjective, it may take the same okurigana, although some may be omitted in certain cases.

- 当たり a-tari (from 当たる a-taru), 怒り ika-ri (from 怒る ika-ru), 釣り tsu-ri (from 釣る tsu-ru), 兆し kiza-shi (from 兆す kiza-su)

For some nouns it is obligatory to omit the okurigana, despite having a verbal origin.

- 話 hanashi (from 話す hana-su), 氷 koori (from 氷る koo-ru) , 畳 tatami (from 畳む tata-mu)

In these cases, the noun form of the corresponding verb does take okurigana.

- 話し hana-shi is the nominal form of the verb 話す hana-su, and not the noun 話 hanashi.

Formally, the verbal noun (VN, still retaining verbal characteristics) takes okurigana, as is usual for verbs, while the deverbal noun (DVN, without verbal characteristics) does not take okurigana, as is usual for nouns.

To understand this grammatical distinction, compare the English present participle (verb form ending in -ing, indicating continuous aspect) and the gerund (noun form of the -ing verb form, which is a verbal noun) versus deverbal forms (which are irregular):[note 6]

- "I am learning Japanese" (verb) and "Learning is fun" (verbal noun) versus the deverbal "Alexandria was a center of learning" (here "learning" is being used as synonymous with "knowledge", rather than an activity)

Similarly, some nouns are derived from verbs, but written with different kanji, in which case no okurigana are used – compare 堀 (hori, "moat") with 掘り (hori, nominal form of 掘る, horu, to dig).

If two different nouns are written with the same kanji, then okurigana are often used for one or both to distinguish readings.

- 幸い saiwa-i, 幸せ shiawa-se, 勢い ikio-i, 勢 sei

However, sometimes okurigana is not used, and the reading is ambiguous:

- 生 nama or ki (×生ま is not used)

Compounds [link]

In compounds, okurigana may be omitted if there is no ambiguity in meaning or reading – in other words, if that compound is only read a single way. If okurigana occur after several characters (esp. both in the middle of the compound and at the end of the compound, as in 2-character compounds), either only the middle okurigana, or both the middle and the final okurigana may be omitted; omitting only the final okurigana but retaining the middle okurigana is rather unusual and somewhat questionable, though not unknown (marked with “?” below).

- 受け付け u-ke tsu-ke, 受付け uke tsu-ke, ?受け付 ?u-ke tsuke, 受付 uke tsuke

- 行き先 i-ki saki, 行先 iki saki

This is particularly done for Japanese compound verbs (the okurigana inflection of the first, main verb is dropped), as above. This is especially common in reducing or removing kana in formulaic constructions, particularly in signs. For example, in the common phrase 立入禁止 (tachi-iri kin-shi, Do not enter; literally, entry prohibited) in analyzed as 立ち入り + 禁止, but the okurigana are usually dropped.

If the compound is unfamiliar to the reader, there is the risk of it being incorrectly read with on readings, rather than the kun readings – for example, 乗入禁止 "drive-in forbidden" is read nori-iri-kin-shi (乗り入り禁止) – the first two characters are a compound verb – but an unfamiliar reader may guess jōnyū-kinshi based on the on readings. However, this is not a problem with familiar compounds, whose reading is already known.

Exceptions [link]

There are however exceptions to these rules that must be learnt: okurigana that has become standard by convention rather than logic.

- 明るい aka-rui – rather than ×明い akaru-i

Formal rules [link]

The Japanese Ministry of Education (MEXT) prescribes rules on how to use okurigana, giving standardized Japanese orthography. The original notification (see references) is from 1973, but it was amended in 1981 when the jōyō kanji table was issued.

The rules apply to kun'yomi (native Japanese readings) of kanji in the jōyō kanji table; they do not apply to kanji outside the jōyō kanji table, or kanji without kun'yomi (with only on'yomi, Chinese readings). The notification gives 7 general rules (通則) and 2 rules for difficult cases (付表の語) in the jōyō kanji table's word list attachment (付表). The first 2 rules (1 & 2) address words that conjugate, the next 3 rules (3–5) address words that do not conjugate, and the last 2 rules (6 & 7) address compound words. Whenever there's doubt whether something is permissible use (許容) or not, the general rule (通則) is to be followed. In some cases, variations are permitted, when there is no danger of confusion; in other case, when there is danger of confusion, variations are not permitted.

Scope:

- The notification provides the basis for okurigana usage in laws, official documents, newspapers, magazines, broadcasts, and similar places where modern Japanese is written using the readings given in the jōyō kanji table.

- The notification does not attempt to regulate the use of okurigana in science, technology, art, and other special fields or in writing of individuals.

- The notification does not apply to proper nouns or kanjis used as symbols.

- Okurigana is not used for on readings, and they are not mentioned in the rules except where necessary.

Examples for each rule, with permitted variations:

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則1) the okurigana usage 書く (for 書 read as かく) and 賢い (for 賢 read as かしこい).

- This rule states that one needs to write (at least) the part of the word that changes under inflection – the last mora.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則1) the okurigana usage 行う (for 行 read as おこなう), but 行なう is also explicitly permitted (通則1許容).

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則2) the okurigana usage 交わる (for 交 read as まじわる). ×交る is not allowed by the rules, because it could be mistaken for 交じる (まじる).

- In Japanese, there are many pairs of transitive/intransitive verbs, some of which differ in the last mora, other of which differ in the second to last mora, as in this example. This is the case illustrated here in 通則2, though the rule also addresses other points.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則2) the okurigana usage 終わる (for 終 read as おわる), but 終る is permitted (通則2許容) because there's no fear of it being misread.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則3) the okurigana usage 花.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則4) the okurigana usage 氷.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則4) the okurigana usage 組. When used as the continuative form of 組む, the form 組み is to be used instead.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則4) the okurigana usage 答え (for 答 read as こたえ), but 答 is permitted (通則4許容) because there's no fear of it being misread.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則5) the okurigana usage 大いに.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則6) the okurigana usage 申し込む (for もうしこむ), but 申込む is permitted (通則6許容) because there's no fear of it being misread.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則6) the okurigana usage 引き換え (for ひきかえ), but 引換え and 引換 are permitted (通則6許容) because there's no fear of their being misread.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則6) the okurigana usage 次々 (iteration mark), but 休み休み (no iteration mark if okurigana is present).

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (通則7) the okurigana usage 身分.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (付表の語1) the okurigana usage 手伝う.

- The 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes (付表の語2) the okurigana usage 名残.

Issues [link]

Variation [link]

While MEXT prescribes rules and permitted variations, in practice there is much variation – permitted or not – particularly in older texts (prior to guidelines) and online – note that these rules are not prescriptive for personal writings, but only in official documents and media. As an example, the standard spelling of the word kuregata is 暮れ方, but it will sometimes be seen as 暮方.

Confusion with compounds [link]

There is a risk of confusion of okurigana with compounds: some Japanese words are traditionally written with kanji, but today some of these kanji are hyōgaiji (uncommon characters), and hence are often written as a mixture of kanji and kana, the uncommon characters being replaced by kana; this is known as mazegaki. The resulting orthography is seen by some as confusing and unsightly, particularly if it is the second character that is written in kana – the kana characters are where okurigana would be expected to go – and this is one motivation for expansions of kanji lists. For example, until the 2010 expansion of the jōyō kanji, the word kanpeki (perfect) was officially written 完ぺき, not as the compound 完璧, since the character 璧 was not on the official list,[1] and takarakuji (lottery) is officially (and also popularly) written as 宝くじ, not as 宝籤, since the second character is not in the jōyō kanji and is also quite complicated. This is less of an issue when the first kanji is written in kana, as in ヤシ殻 (yashi-kaku, coconut shell), which is formally 椰子殻.

Other affixes [link]

Japanese has various affixes, some of which are written in kana and should not be confused with okurigana. Most common are the honorifics, which are generally suffixes, such as 〜さん -san (Mr., Ms.), and bikago (美化語, "beautified language"), such as お〜 and ご〜 as in お茶 (ocha, green tea).

Notes [link]

- ^ Verbs with Chinese roots are instead a word + する (suru, to do), and only the する, which is a separate word, inflects.

- ^ Do not confuse 上る with its homophone, 登る (both pronounced "noboru"). One meaning of 登る is "to climb (especially with hands and feet)".

- ^ Compare 起こる/起こす (おこる、おこす, o-koru, o-kosu), which does use こ.

- ^ 止る is sometimes used for 止まる (とまる, to-maru), the intransitive version of 止める (とめる, to-meru), however.

- ^ In this example, the non-standard okurigana 行なう oko-nau is sometimes used for clarity.

- ^ Alternatively, compare "converse" (verb) with "conversation" (verbal noun, act of conversing) with "conversation" (deverbal noun, episode noun – the time period), which corresponds with Japanese 話す/話し/話.

References [link]

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2010) |

- ^ Japan Times, Get set for next year's overhaul of official kanji, 21 October 2009, retrieved 27 February 2010.

https://wn.com/Okurigana

Podcasts:

-

by Buck O Nine

You Go You're Gone

by: Buck O NineWell, Tommy stepped away

From the world for awhile

He only left a picture

Of a seventh grade smile

Well, he got caught in between

A mother's lost hope

And a father's lost dream

A head of ideas

That don't mean anything

That don't mean anything

Well, Tommy had a problem

With being alone

He spent everyday

Of his life on his own

But there's no one to blame

It's hard to keep friends

When you keep moving away

The cards and letters

They don't mean anything

They don't mean anything

And when you go, you go

You go, you go

When you're gone, you're gone

You're gone, you're gone

And if you feel you can't go on

You can always come home

You can always come home

You can always come home to me

Tommy stepped away

From the world for awhile

His first few steps

It felt like a mile

They never could believe

He said good-bye

And they just watched him leave

All the things he knew

Don't mean anything

They don't mean anything

And when you go, you go

You go, you go

When you're gone, you're gone

You're gone, you're gone

And if you feel you can't go on

You can always come home

You can always come home

You can always come home to me

And if you go too far

You might never come back

And I might go too far

But I won't ever some back

And when you go, I'll wait for you

And when you go, I'll be there too

And when you go, you go

You go, you go

When you're gone, you're gone

You're gone, you're gone

And if you feel you can't go on