| This article is outdated. Please update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. Please see the talk page for more information. (May 2012) |

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (RS)-1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine | |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy cat. | C[1] |

| Legal status | Prohibited (S9) (AU) Schedule III (CA) CD Lic (UK) Schedule I (US) |

| Routes | Oral, sublingual, insufflation, inhalation (vaporization), injection,[2] rectal |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, CYP450 extensively involved, especially CYP2D6 |

| Half-life | 6–10 hours (though duration of effects is typically actually 3–5 hours) |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 42542-10-9 |

| ATC code | N/A |

| PubChem | CID 1615 |

| DrugBank | DB01454 |

| ChemSpider | 1556 |

| UNII | KE1SEN21RM |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:1391 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL43048 |

| Synonyms | (±)-1,3-benzodioxolyl-N-methyl-2-propanamine; (±)-3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methyl-α-methyl-2-phenethylamine; DL-3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine; methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 193.25 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

|

|

| |

|

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine; methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is an entactogenic drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine classes of drugs. In popular culture, MDMA has become widely known as "ecstasy", usually referring to its street pill form, although this term may also include the presence of possible adulterants. The terms "molly" (allegedly derived from "molecule") and "mandy" (a corruption of "MDMA") colloquially refer to MDMA in crystalline and/or powder form, usually implying purity.

MDMA can induce euphoria, a sense of intimacy with others, and diminished anxiety. Many studies, particularly in the fields of psychology and cognitive therapy, have suggested that MDMA has therapeutic benefits and facilitates therapy sessions in certain individuals, a practice for which it had formally been used in the past. Clinical trials are now testing the therapeutic potential of MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety associated with terminal cancer.[3][4]

MDMA is criminalized in most countries, though some important civil society initiatives, such as the Global Commission on Drug Policy, are not concerned with putting a stop to it, but with educating the public about the drug,[5] and its possession, manufacture, or sale may result in criminal prosecution, although some limited exceptions exist for scientific and medical research. For 2008 the UN estimated between 10–25 million people globally used ecstasy at least once in the past year. This was broadly similar to the number of cocaine, amphetamine and opiate users, but far fewer than the global number of cannabis users.[6] It is taken in a variety of contexts far removed from its roots in psychotherapeutic settings and is commonly associated with dance parties (or "raves") and electronic dance music.[7]

Regulatory authorities in several locations around the world have approved scientific studies administering MDMA to humans to examine its therapeutic potential and its effects.[8]

Contents |

Medical use [link]

There have long been suggestions that MDMA might be useful in psychotherapy, facilitating self-examination with reduced fear.[9][10][11] Indeed, some therapists, including Leo Zeff, Claudio Naranjo, George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson, used MDMA in their practices until it was made illegal. George Greer synthesized MDMA in the lab of Alexander Shulgin and administered it to about 80 of his clients over the course of the remaining years preceding MDMA's Schedule I placement in 1985. In a published summary of the effects,[12] the authors reported patients felt improved in various, mild psychiatric disorders and experienced other personal benefits, especially improved intimate communication with their significant others. In a subsequent publication on the treatment method, the authors reported that one patient with severe pain from terminal cancer experienced lasting pain relief and improved quality of life.[13]

Three neurobiological mechanisms for the therapeutic effects of MDMA have been suggested: "1) MDMA increases oxytocin levels, which may strengthen the therapeutic alliance; 2) MDMA increases ventromedial prefrontal activity and decreases amygdala activity, which may improve emotional regulation and decrease avoidance, and 3) MDMA increases norepinephrine (NE) release and circulating cortisol levels, which may facilitate emotional engagement and enhance extinction of learned fear associations."[14]

The first phase-II double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial into the potential therapeutic benefits of using the drug as an augment to psychotherapy showed that most patients in the trial given psychotherapy treatment along with doses of MDMA experienced statistically significant reductions in the severity of their condition after two months, compared with a control group receiving psychotherapy and a placebo.[15] The authors concludes "MDMA-assisted psychotherapy can be administered to posttraumatic stress disorder patients without evidence of harm, and it may be useful in patients refractory to other treatments."[15]

The possible therapeutic potential of MDMA is being tested in several ongoing studies, some sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Studies in the U.S., Switzerland, and Israel are evaluating the efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treating those diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or anxiety related to cancer.

Small doses of MDMA are used as an entheogen to enhance meditation by some Buddhist Monks.[16]

Recreational use [link]

- Prices are from cited sources, they may differ in reality.

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction notes that, although there are some reports of tablets being sold for as little as €1, most countries in Europe now report typical retail prices in the range of €3 to €9 per tablet.[17] The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claimed in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical U.S. retail prices are lower, costing 20 to 25 per tablet, or from 3 to 10 per tablet if bought in batches[18] MDMA is expensive in Australia, costing A$20–A,0 per tablet, but in the Asian community it is A 0–30, depending on the size. In terms of purity data for Australian MDMA, the average is around 34%, ranging from less than 1% to about 85%. The majority of tablets contain 70–85 mg of MDMA. Most MDMA enters Australia from different markets, the Netherlands, the UK, Asia, and the U.S.[19]

MDMA is occasionally known for being taken in conjunction with psychedelic drugs, such as LSD or psilocybin mushrooms, or even common drugs such as cannabis. As this practice has become more prevalent, most of the more common combinations have been given nicknames, such as "candy flipping", for MDMA combined with LSD, "MX Missile" (or "Hippy Flipping" in some circles) for MDMA with psilocybin, or "kitty flipping" for MDMA with ketamine.[20] The term "flipping" may come from the subjective effects of using MDMA with a psychedelic in which the user may shift rapidly between a more lucid state and a more psychedelic state several times during the course of their experience. Many users use mentholated products while taking MDMA for its cooling sensation while experiencing the drug's effects. Examples include menthol cigarettes, Vick's Vapo Rub, NyQuil,[21] and lozenges.

Subjective effects [link]

The primary effects attributable to MDMA consumption are predictable and fairly consistent among users. In general, users report feeling effects within 45 minutes to an hour of consumption, hitting a peak at approximately 2 1/2 to 3 hours, reaching a plateau that lasts about 2–3 hours, followed by a comedown of a few hours. After the drug has run its course, many users report feeling fatigue; other, more long-lasting effects such as diminished mental capacity, permanent sensitivity to light, paranoia, and impaired cognitive ability have also been reported.

The most common effects reported by users include:[22]

- A general and subjective alteration in consciousness

- A strong sense of inner peace and self-acceptance

- Diminished aggression, hostility, and jealousy

- Diminished fear, anxiety, and insecurity

- Extreme mood lift with accompanying euphoria

- Feelings of empathy, compassion, and forgiveness toward others

- Feelings of intimacy and even love for others

- Improved self-confidence

- The ability to discuss normally anxiety-provoking topics with marked ease

- An intensification of all of the bodily senses (hearing, touch, smell, vision, taste)

- Substantial enhancement of the appreciation of music quality

- Mild psychedelia, consisting of mental imagery and auditory and visual distortions

- Stimulation, arousal, and hyperactivity (e.g., many users get an "uncontrollable urge to dance" while under the influence)

- Increased energy and endurance

- Increased alertness, awareness, and wakefulness

- Increased desire, drive, and motivation

- Analgesia or decreased pain sensitivity

Adverse effects [link]

In January 2001, an overview of the subjective side-effects of MDMA was published by Liechti, Gamma, and Vollenweider in the journal Psychopharmacology. Their paper was based on clinical research conducted over several years involving 74 healthy volunteers. The researchers found that there were a number of common side-effects and that many of the effects seemed to occur in different amounts based on gender. The top side-effects reported were difficulty concentrating, jaw clenching, grinding of the teeth during sleep, lack of appetite, and dry mouth/thirst (all occurring in more than 50% of the 74 volunteers). Liechti, et al. also measured some of the test subjects for blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature against a placebo control but no statistically significant changes were seen.[23][24]

A 2011 study carried out by Harvard Medical School and published in the journal Addiction found no signs of cognitive impairment due to ecstasy use, and that it did not decrease mental ability. The report also raised concerns that previous methods used to conduct that research on ecstasy had been flawed, and the experiments overstated the cognitive differences between ecstasy users and nonusers.[25]

However, a study from John Hopkins Medical School in 2008 found a slight, but significant correlation of cognitive deficiency in MDMA users, but admitted that this data may be confounded by other illicit drug use. The significant finding of the article was the serotonergic neurotoxicity in stacked doses and a lasting decrease in serotonin reuptake (SERT) binding. In rats, high doses and in high temperatures, serotonergic neurotoxicity is limited and dopaminergic neurotoxicity occurs. However, rats may not be a generalizable model for human neurotoxicity studies. [26]

After-effects [link]

Effects reported by some users once the acute effects of MDMA have worn off include:

- Psychological

- Anxiety and paranoia[27]

- Depression[27][28][29][30][31][32]

- Irritability[30]

- Fatigue[31][32]

- Impaired attention, focus, and concentration,[29] as well as drive and motivation (due to depleted serotonin levels)[28]

- Residual feelings of empathy, emotional sensitivity, and a sense of closeness to others (afterglow)

- Physiological

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, or vertigo[32]

- Loss of appetite[28][29]

- Gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea or constipation[27]

- Insomnia[27][28][29]

- Aches and pains, usually from excessive physical activity (e.g., dancing)[28][29][31]

- Exhaustion[30][32]

- Jaw soreness, from bruxism[32][33][34]

A slang term given to the depressive period following MDMA consumption is Tuesday Blues (or "Suicide Tuesday"), referring to the low mood that can be experienced midweek by depleted serotonin levels following weekend MDMA use. Some users report that consuming 5-HTP, L-Tryptophan and vitamins the day after use can reduce the depressive effect by replenishing serotonin levels (magnesium supplements are also used prior to or during use).[35]

Overdose [link]

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2009) |

Upon overdose, the potentially serious serotonin syndrome, stimulant psychosis, and/or hypertensive crisis, among other dangerous adverse reactions, may come to prominence, the symptoms of which can include the following:

- Psychological

- Disorientation and/or confusion

- Anxiety, paranoia, and/or panic attacks

- Hypervigilance or increased sensitivity to perceptual stimuli, accompanied by significantly increased threat detection

- Hypomania or full-blown mania

- Derealization and/or depersonalization

- Hallucinations and/or delusions[36]

- Thought disorder or disorganized thinking

- Cognitive and memory impairment potentially to the point of retrograde or anterograde amnesia[37]

- Acute delirium

- Physiological

- Myoclonus or involuntary and intense muscle twitching

- Nystagmus or involuntary eye movements

- Hyperreflexia or overresponsive or overreactive reflexes[38]

- Tachypnoea or rapid breathing and/or dyspnea or shortness of breath

- Palpitations or abnormal awareness of the beating of the heart

- Angina pectoris or severe chest pain, as well as pulmonary hypertension (PH)[39]

- Cardiac arrhythmia or abnormal electrical activity of the heart

- Circulatory shock or cardiogenic shock

- Vasculitis or destruction of blood vessels[40]

- Cardiotoxicity or damage to the heart[41]

- Cardiac dysfunction, arrest, myocardial infarction, and/or heart failure[42][43][44]

- Hemorrhage and/or stroke[45][46]

- Severe hyperthermia, potentially resulting in organ failure[47][48]

- Syncope or fainting or loss of consciousness

- Organ failure (as mentioned above)

- Possible brain damage

- Coma or death

Chronic use [link]

Some studies indicate that repeated recreational users of MDMA have increased rates of depression and anxiety, even after quitting the drug.[49][50] A meta-analytic review of the published literature on memory show that ecstasy users may suffer short-term and long-term verbal memory impairment—with 70–80% of ecstasy users displaying impaired memory. Moreover, this research shows the amount of doses consumed does not significantly predict memory performance.[51] Other meta analyses have reported possibility of impairment of executive functioning.[52] Despite these findings many factors including total lifetime MDMA consumption, the duration of abstinence between uses, dosage, the environment of use, poly-drug use/abuse, quality of mental health, various lifestyle choices, and predispositions to develop clinical depression and other disorders have made the results of many studies difficult to verify. A study that attempted to eliminate these confounding factors was published in February, 2011 by Addiction, and found few differences in the cognitive functioning of MDMA-using ravers versus non-MDMA-using ravers, "In a study designed to minimize limitations found in many prior investigations, we failed to demonstrate marked residual cognitive effects in ecstasy users. This finding contrasts with many previous findings-including our own-and emphasizes the need for continued caution in interpreting field studies of cognitive function in illicit ecstasy users."[53] MDMA use has been occasionally associated with liver damage,[54] excessive wear of teeth,[55] and (very rarely) hallucinogen persisting perception disorder.[56]

Short-term health concerns [link]

Short-term physical health risks of MDMA consumption include hyperthermia,[59][60] and hyponatremia.[61] Continuous activity without sufficient rest or rehydration may cause body temperature to rise to dangerous levels, and loss of fluid via excessive perspiration puts the body at further risk as the stimulatory and euphoric qualities of the drug may render the user oblivious to their energy expenditure for quite some time. Diuretics such as alcohol may exacerbate these risks further.

Long-term effects on serotonin and dopamine [link]

MDMA causes a reduction in the concentration of serotonin transporters (SERTs) in the brain. The rate at which the brain recovers from serotonergic changes is unclear. One study demonstrated lasting serotonergic changes in some animals exposed to MDMA.[62] Other studies have suggested that the brain may recover from serotonergic damage.[63][64]

Some studies show that MDMA may be neurotoxic in humans.[65][66] Other studies, however, suggest that any potential brain damage may be at least partially reversible following prolonged abstinence from MDMA.[64][67] Depression and deficits in memory have been shown to occur more frequently in long-term MDMA users.[68][69] However, some recent studies have suggested that MDMA use may not be associated with chronic depression.[70][71]

One study on MDMA toxicity, by George A. Ricaurte of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, which claimed that a single recreational dose of MDMA could cause Parkinson's Disease in later life due to severe dopaminergic stress, was actually retracted by Ricaurte himself after he discovered his lab had administered not MDMA but methamphetamine, which is known to cause dopaminergic changes similar to the serotonergic changes caused by MDMA.[72] Ricaurte blamed this mistake on a labeling error by the chemical supply company that sold the material to his lab, but the supply company responded that there was no evidence of a labeling error on their end. Most studies have found that levels of the dopamine transporter (or other markers of dopamine function) in MDMA users deserve further study or are normal.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79]

Several studies have indicated a possible mechanism for neurotoxicity is a metabolite of MDMA, through the reaction of Alpha-Methyldopamine, a principal metabolite, and glutathione, the major antioxidant in the human body. One possible product of this reaction, 2,5-bis-(glutathion-S-yl)-alpha-methyldopamine, has been demonstrated to produce the same toxic effects observed in MDMA, while MDMA, and alpha-methyldopamine themselves have been shown to be non-neurotoxic. It is, however, impossible to avoid the metabolism of MDMA in the body, and the production of this toxic metabolite.[80][81][82] Some studies have demonstrated possible ways to minimize the production of this particular metabolite, though evidence at this point is sparse at best.

Purity and dosage of "ecstasy" [link]

Another concern associated with MDMA use is toxicity from chemicals other than MDMA in ecstasy tablets. Due to its near-universal illegality, the purity of a substance sold as ecstasy is unknown to the typical user. The MDMA content of tablets varies widely between regions and different brands of pills and fluctuates somewhat each year. Pills may contain other active substances meant to stimulate in a way similar to MDMA, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, caffeine, all of which may be comparatively cheap to produce and can help to boost overall profits. In some cases, tablets sold as ecstasy do not even contain any MDMA. Instead they may contain an assortment of undesirable drugs and substances, such as paracetamol, ibuprofen, talcum powder, etc.[83]

There have been a number of deaths attributed to para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA), a potent and highly neurotoxic hallucinogenic amphetamine, being sold as ecstasy.[84][85] PMA is unique in its ability to quickly elevate body temperature and heart rate at relatively low doses, especially in comparison to MDMA. Hence, a user believing he is consuming two 120 mg pills of MDMA could actually be consuming a dose of PMA that is potentially lethal, depending on the purity of the pill. Not only does PMA cause the release of serotonin but it also acts as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, MAOI. When combined with an MDMA or an MDMA-like substance, serotonin syndrome can result.[86] Combining MAO inhibitors with certain legal prescription and over the counter medications can also lead to (potentially fatal) serotonin syndrome.

EU trends in MDxx sales and piperazines [link]

| This unreferenced section requires citations to ensure verifiability. |

Benzylpiperazine (BZP), 3-Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TMFPP) and meta-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) are three substances that were common in over the counter legal highs until recently, BZP being listed in the UK controlled substances act as of 2009. They belong to the phenylpiperazines, as opposed to the phenethylamines that account for MDMA ('ecstasy'), MDA, MDEA, amphetamine ('speed'), methamphetamine ('crystal meth'), etc. Despite being temporarily legal and belonging to an entirely different class of compound, they (in particular BZP) were able to produce effects comparable to the already illegal amphetamines; particularly those of amphetamine itself.

Their amphetamine like qualities were noticed in the 1970s but remained overshadowed by actual phenethylamines, narrowly avoiding addition to the amphetamine controls. During the early 1990s, the DEA noticed BZP being used as a cut or adulterant in synthetic street drugs. During this period, Total Synthesis 2 was published, The Hive had come online, numerous phenethylamine based 'Research Chemicals' (e.g. 2C-B) were flooding out and many small scale labs were set up in the West, producing materials such as MDA / MDMA. These were already illegal, whereas substances such as 2C-I and 2C-B were not. However, Europe (and particularly the Netherlands at the time) were the main producers of these substances. Over the course of the late 1990s, suppliers to the labs became more cautious with regards to certain precursors or necessary reagents for amphetamine production. It is possible that larger commercial scale laboratories suspected a ban on 2C's may be set in place soon after. BZP and the other piperazine based compounds became of more commercial interest and began appearing as over the counter highs.

Between 2001 and 2004, a number of key events occurred, such as the shutting down of the hive and the placing of safrole (the most easily available and direct precursor to MDxx) under EU regulation. Safrole was also rapidly removed from perfumes, soaps and food additives. As the oil is produced by trees not native to Europe and preferring sunny climates, this made production of MDxx considerably more tedious. There has been a gradual drop in MDMA seizures within Europe since 2004. Instead, producers of amphetamines moved closer to the sources of precursor and a large market to sell through; East and South East Asia.

Simultaneously, suspicions that BZP was being passed off as MDMA were raised by users. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, as well as the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, have now discovered this to be correct, with the percentage of piperazine increasing in the 'ecstasy-group' (MDxx) seizures, particularly around Europe.

According the annual EU and UN reports, up to 50% of what was being sold as 'MDMA', 'X', 'Xtc' or 'Ecstasy' during the period of 2005 to 2010 was piperazine based rather than amphetamine. Some frequent drug users have claimed an ability to differentiate between regular amphetamines and substances such as BZP, often noting BZP to be a somewhat 'softer' version of amphetamine and, in particular and when taken alone, a distinct lack of MDMAs hallmark depth of empathy. This was addressed, to an extent, in the legal highs, with TMFPP and mCPP (also from the piperazines) being taken alongside BZP to increase the depth of empathy felt. Despite this, BZP (prior to it's prominence as a legal high) had proven indistinguishable from actual amphetamine ('speed') in a 1970's trial for the European Journal of Pharmacology involving former amphetamine users. As a legal high, it enjoyed a recognizable product placement for about a decade (from around 1995 to 2009 with regards to the UK ban). During this period, legal high manufacturers and others felt the piperazines to be a viable harm reduction tool, with some customers preferring to buy the standardised piperazines over street obtained amphetamines. Tens of millions of doses were sold over the span with only a handful of serious medical complications being noted. The effects are largely those of amphetamine, but with a tolerance build rate that seems to prevent multiday / week long runs (these often being the starting point of the more serious negative impacts of routine amphetamine and methamphetamine abuse). This would appear to make it a safer alternative than some amphetamine analogues; e.g. para-methoxyamphetamine and the potent Bromo-DragonFly.

As of 2009, the European Commission requested all member states place BZP under control, adding it as a listed substance on the UN Convention for Psychotropics.

Passing off of piperazines as amphetamines of some sort (speed or MDxx for example) was predictable given the similar effect profiles; these would likely have convinced the vast majority of new, infrequent and many frequent users into thinking that they had bought MDxx or amphetamine. As importantly, the piperazines could be easily and cheaply obtained, then resold by dealers as more exotic (and costly) illegal substances, with a gram of street MDMA costing from £35 to £50 in London and potentially being only 20 to 50% pure, versus BZP at tens of pence or less per pure gram (containing ten, full 100mg doses).

Tailing off was also predictable; although UK sellers where given three months to clear their remaining stock, with the full EU ban being implemented after a year's notice, there could easily have been old stock remaining in storage around Europe.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime 2011 report, covering 2010, did not comment on the presence of piperazine substitution in these amphetamine markets, but it mentions approximately 3,000 litres in total of safrole being seized in Latvia and Lithuania, with Eastern Europe member states beginning to present higher usage rates of MDMA. In general the presence of piperazine substitution will have undoubtedly skewed numerous MDxx / amphetamine user figures for the previous five or ten year period. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) commented on active MDMA pill contents in EU member states ranging from 3 to 100 and in some cases 130mg for Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Turkey, Germany and Bulgaria. In general, though, a steady decline in MDMA content has occurred since 2004 (coinciding with the control of safrole and closure of the Hive).

The 2011 EMCDDA report goes on to mention piperazine prevalence in amphetamines around Europe still remaining notably high. The price of MDxx, in general, has been declining. It would be reasonable to propose this is in part due to long term users encountering piperazine materials. With the piperazines being so cheap on their departure from a legal product status, there will be greater incentive for resellers to cut prices and move stock; something that would be less feasible with actual MDxx given the increasing difficultly in obtaining the precursor.

A questionable reappearance in 2010 is that of PMA and PMMA being sold as MDxx. This has curiously appeared predominately in the Netherlands, a country with a history of being an MDxx and piperazine production hotspot, both of which are safer than PMA. Autria and Norway were simultaneously affected by PMA. All three reported hospitalisations and deaths.

110 new psychoatives were reported to the EMCDDA from 1997 to 2009. In 2009, the European early-warning system received 24 notifications of possible new problem trends. For the year 2010, this jumped to more than 40. Some of these were phenethylamine based, the others being tryptamines, synthetic cannabinoids ('Spice'), cathinones (mephedrone) and piperazines. The European markets have come under a form of legal high, analogue bombardment. Worryingly, in light of the UK's drug advisory board fracturing over David Nutt's forced retirement, a number of EU member states have looked into implementing 'emergency / generic' control acts.

Harm assessment [link]

The UK study placed great weight on the risk for acute physical harm, the propensity for physical and psychological dependency on the drug, and the negative familial and societal impacts of the drug. They did not evaluate or rate the negative impact of ecstasy on the cognitive health of ecstasy users, e.g., impaired memory and concentration. Based on these factors, the study placed MDMA at number 18 in the list of 20 popular drugs.[87]

David Nutt, a former chairman of the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, stated in the Journal of Psychopharmacology in January 2009 that ecstasy use compared favorably with horse riding in terms of risk, with ecstasy leading to around 30 deaths a year in the UK compared to about 10 from horse riding, and "acute harm to person" occurring in approximately 1 in 10,000 episodes of ecstasy use compared to about 1 in 350 episodes of horse riding.[88] Dr. Nutt notes the lack of a balanced risk assessment in public discussions of MDMA:[88]

The general public, especially the younger generation, are disillusioned with the lack of balanced political debate about drugs. This lack of rational debate can undermine the trust in government in relation to drug misuse and thereby undermining the government's message in public information campaigns. The media in general seem to have an interest in scare stories about illicit drugs, though there are some exceptions (Horizon, 2008).[89] A telling review of 10-year media reporting of drug deaths in Scotland illustrates the distorted media perspective very well (Forsyth, 2001).[90] During this decade, the likelihood of a newspaper reporting a death from paracetamol was in [sic] per 250 deaths, for diazepam it was 1 in 50, whereas for amphetamine it was 1 in 3 and for ecstasy every associated death was reported.

A spokesperson for the ACMD said that "The recent article by Professor David Nutt published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology was done in respect of his academic work and not as chair of the ACMD."[91]

The most carefully designed study so far was published in February 2011[92] in the journal Addiction, comparing the effect on cognitive skills in 52 ecstasy users against 59 very closely matched non-users. The study, performed by the group of Prof. Halpern of Harvard Medical School, eliminated potential confounding factors like the use of other drugs and history of drug-use. The study found no short- or long-term differences in cognitive skills in the test group (users) versus the control group (non-users).

Drug interactions [link]

There are a number of reported potentially dangerous possible interactions between MDMA and other drugs, including serotonergic drugs.[93] Several cases have been reported of death in individuals who ingested MDMA while taking ritonavir (Norvir), which inhibits multiple CYP450 enzymes. Toxicity or death has also been reported in people who took MDMA in combination with certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate), or moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix).[94] On the other hand, MAOB inhibitors like selegiline (Deprenyl; Eldepryl, Zelapar, Emsam) do not seem to carry these risks when taken at selective doses, and have been used to completely block neurotoxicity in rats.[95]

Commercial sassafras oil generally is a by-product of camphor production in Asia or comes from related trees in Brazil. Safrole is a precursor for the clandestine manufacture of MDMA (ecstasy), and as such, its transport is monitored internationally. Roots of Sassafras can also be steeped to make tea and were used in the flavoring of traditional root beer until being banned for mass production by the FDA. Laboratory animals that were given oral doses of sassafras tea or sassafras oil that contained large doses of safrole developed permanent liver damage or various types of cancer. In humans liver damage can take years to develop and it may not have obvious signs.

Chemistry [link]

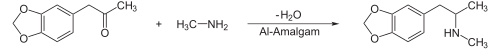

Safrole, a colorless or slightly yellow oily liquid, extracted from the root-bark or the fruit of the sassafras tree is the primary precursor for all manufacture of MDMA. There are numerous synthetic methods available in the literature to convert safrole into MDMA via different intermediates.[96][97][98][99] One common route is via the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone, also known as piperonyl acetone) intermediate. This intermediate can be produced in at least two different ways. One method is to isomerize safrole to isosafrole in the presence of a strong base and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another, reportedly better,[citation needed] method is to make use of the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxy phenyl-2-propanone) intermediate. This can be done with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been prepared, a reductive amination leads to MDMA, a racemate {1:1 mixture of (R)-1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine and (S)-1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine}. Another method for the synthesis of racemic MDMA is addition of hydrogen bromide to safrole and reaction of the adduct with methylamine.

Relatively small quantities of essential oil are required to make large numbers of MDMA pills. The essential oil of Ocotea cymbarum typically contains between 80 and 94% safrole. This would allow 500 ml of the oil, which retails at between $20 and $100, to be used to produce an estimated 1,300 to 2,800 tablets containing approximately 120 mg of MDMA each.[100]

Pharmacology [link]

MDMA acts as a releasing agent of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine (DA).[101] It enters neurons via carriage by the monoamine transporters.[101] Once inside, MDMA inhibits the vesicular monoamine transporter, which results in increased concentrations of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the cytoplasm,[102] and induces their release by reversing their respective transporters through a process known as phosphorylation.[103]

MDMA has been identified as a potent agonist of TAAR1, a newly discovered GPCR important for regulation of monoaminergic systems in the brain.[104] Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation and inhibits transporter function.[104][105][106][107][108] These effects increase monoamine efflux and prolong the amount of time monoamines remain in the synapse. It also acts as a weak 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptor agonist, and its more efficacious metabolite MDA likely augments this action.[109][110][111][112]

MDMA's unusual entactogenic effects have been hypothesized to be, at least partly, the result of indirect oxytocin secretion via activation of the serotonin system.[113] Oxytocin is a hormone released following events like hugging, orgasm, and childbirth, and is thought to facilitate bonding and the establishment of trust.[114] Based on studies in rats, MDMA is believed to cause the release of oxytocin, at least in part, by both directly and indirectly agonizing the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor. A placebo-controlled study in 15 human volunteers found that 100 mg MDMA increased blood levels of oxytocin, and the amount of oxytocin increase was correlated with the subjective prosocial effects of MDMA.[115]

Pharmacokinetics [link]

MDMA reaches maximal concentrations in the blood stream between 1.5 and 3 hours after ingestion.[116] It is then slowly metabolized and excreted, with levels of MDMA and its metabolites decreasing to half their peak concentration over approximately 8 hours.[117] Thus, there are still high MDMA levels in the body when the experiential effects have mostly ended, indicating that acute tolerance has developed to the actions of MDMA. Taking additional supplements of MDMA at this point, therefore, produces higher concentrations of MDMA in the blood and brain than might be expected based on the perceived effects.

Metabolites of MDMA that have been identified in humans include 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-methamphetamine (HMMA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine (HMA), 3,4-dihydroxyamphetamine (DHA) (also called alpha-methyldopamine (α-Me-DA)), 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylacetone (MDP2P), and N-hydroxy-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDOH). The contributions of these metabolites to the psychoactive and toxic effects of MDMA are an area of active research. Sixty-five percent of MDMA is excreted unchanged in the urine (in addition, 7% is metabolized into MDA) during the 24 hours after ingestion.[118]

MDMA is known to be metabolized by two main metabolic pathways: (1) O-demethylenation followed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-catalyzed methylation and/or glucuronide/sulfate conjugation; and (2) N-dealkylation, deamination, and oxidation to the corresponding benzoic acid derivatives conjugated with glycine. The metabolism may be primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes (CYP2D6 (in humans, but CYP2D1 in mice), and CYP3A4) and COMT. Complex, nonlinear pharmacokinetics arise via autoinhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP2D8, resulting in zeroth order kinetics at higher doses. It is thought that this can result in sustained and higher concentrations of MDMA if the user takes consecutive doses of the drug.

Because the enzyme CYP2D6 is deficient or totally absent in some people,[119] it was once hypothesized that these people might have elevated risk when taking MDMA. However, there is still no evidence for this theory and available evidence argues against it.[120] It is now thought that the contribution of CYP2D6 to MDMA metabolism in humans is less than 30% of the metabolism. Indeed, an individual lacking CYP2D6 was given MDMA in a controlled clinical setting and a larger study gave MDMA to healthy volunteers after inhibiting CYP2D6 with paroxetine. Lack of the enzyme caused a modest increase in drug exposure and decreases in some metabolites, but physical effects did not appear appreciably elevated. While there is little or no evidence that low CYP2D6 activity increases risks from MDMA, it is likely that MDMA-induced CYP2D inhibition will increase risk of those prescription drugs that are metabolized by this enzyme. MDMA-induced CYP2D inhibition appears to last for up to a week after MDMA exposure.

MDMA and metabolites are primarily excreted as conjugates, such as sulfates and glucuronides.[121]

MDMA is a chiral compound and has been almost exclusively administered as a racemate. However, the two enantiomers have been shown to exhibit different kinetics. (S)-MDMA is more effective in eliciting 5-HT, NE, and DA release, while (D)-MDMA is overall less effective, and more selective for 5-HT and NE release (having only a very faint efficacy on DA release).[122] The disposition of MDMA may also be stereoselective, with the S-enantiomer having a shorter elimination half-life and greater excretion than the R-enantiomer. Evidence suggests[123] that the area under the blood plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was two to four times higher for the (R)-enantiomer than the (S)-enantiomer after a 40 mg oral dose in human volunteers. Likewise, the plasma half-life of (R)-MDMA was significantly longer than that of the (S)-enantiomer (5.8 ± 2.2 hours vs 3.6 ± 0.9 hours). However, because MDMA excretion and metabolism have nonliniar kinetics,[124] the half-lives would be higher at more typical doses (100 mg is sometimes considered a typical dose[116]). Given as the racemate MDMA has a half-life of around 8 hours.

Detection of use [link]

MDMA and MDA may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Some drug abuse screening programs rely on hair, saliva, or sweat as specimens. Most commercial amphetamine immunoassay screening tests cross-react significantly with MDMA or its major metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and separately measure each of these substances. The concentrations of MDA in the blood or urine of a person who has taken only MDMA are, in general, less than 10% those of the parent drug.[125][126][127]

History [link]

|

|

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United Kingdom and United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article and discuss the issue on the talk page. (July 2010) |

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch. At the time, Merck was interested in developing substances that stopped abnormal bleeding. Merck wanted to evade an existing patent, held by Bayer, for one such compound: hydrastinine. At the behest of his superiors Walther Beckh and Otto Wolfes, Köllisch developed a preparation of a hydrastinine analogue, methylhydrastinine. MDMA was an intermediate compound in the synthesis of methylhydrastinine, and Merck was not interested in its properties at the time.[128] On 24 December 1912, Merck filed two patent applications that described the synthesis of MDMA[129] and its subsequent conversion to methylhydrastinine.[130]

Over the following 65 years, MDMA was largely forgotten. Merck records indicate that its researchers returned to the compound sporadically. In 1927, Max Oberlin studied the pharmacology of MDMA and observed that its effects on blood sugar and smooth muscles were similar to ephedrine's. Researchers at Merck conducted experiments with MDMA in 1952 and 1959.[128] In 1953 and 1954, the United States Army commissioned a study of toxicity and behavioral effects in animals of injected mescaline and several analogues, including MDMA. These originally classified investigations were declassified and published in 1973.[131] The first scientific paper on MDMA appeared in 1958 in Yakugaku Zasshi, the Journal of the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan. In this paper, Yutaka Kasuya described the synthesis of MDMA, a part of his research on antispasmodics.[132]

MDMA was being used recreationally in the United States by 1970.[133] In the mid-1970s, Alexander Shulgin, then at University of California, Berkeley, heard from his students about unusual effects of MDMA; among others, the drug had helped one of them to overcome his stutter. Intrigued, Shulgin synthesized MDMA and tried it himself in 1976.[134] Two years later, he and David E. Nichols published the first report on the drug's psychotropic effect in humans. They described "altered state of consciousness with emotional and sensual overtones" that can be compared "to marijuana, and to psilocybin devoid of the hallucinatory component".[135]

Shulgin took to occasionally using MDMA for relaxation, referring to it as "my low-calorie martini", and giving the drug to his friends, researchers, and other people who he thought could benefit from it. One such person was psychotherapist Leo Zeff, who had been known to use psychedelics in his practice. Zeff was so impressed with the effects of MDMA that he came out of his semi-retirement to proselytize for it. Over the following years, Zeff traveled around the U.S. and occasionally to Europe, training other psychotherapists in the use of MDMA.[134][136][137] Among underground psychotherapists, MDMA developed a reputation for enhancing communication during clinical sessions, reducing patients' psychological defenses, and increasing capacity for therapeutic introspection.[138]

In the early 1980s in the U.S., MDMA rose to prominence as "Adam" in trendy nightclubs and gay dance clubs in the Dallas area.[139] From there, use spread to raves in major cities around the country, and then to mainstream society. The drug was first proposed for scheduling by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in July 1984[140] and was classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the U.S. on 31 May 1985.[141]

In the late 1980s MDMA, known by that time as "ecstasy", began to be widely used in the UK and other parts of Europe, becoming an integral element of rave culture and other psychedelic-influenced music scenes. Spreading along with rave culture, illicit MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later in high schools. MDMA became one of the four most widely used illicit drugs in the U.S., along with cocaine, heroin, and cannabis.[142] According to some estimates as of 2004, only marijuana attracts more first time users in the U.S.[142]

After MDMA was criminalized, most medical use stopped, although some therapists continued to prescribe the drug illegally. Later Charles Grob initiated an ascending-dose safety study in healthy volunteers. Subsequent legally-approved MDMA studies in humans have taken place in the U.S. in Detroit (Wayne State University), Chicago (University of Chicago), San Francisco (UCSF and California Pacific Medical Center), Baltimore (NIDA–NIH Intramural Program), and South Carolina, as well as in Switzerland (University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zürich), the Netherlands (Maastricht University), and Spain (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).[143]

In 2010, the BBC reported that use of MDMA had decreased in the UK in previous years. This is thought to be due to increased seizures and decreased production of the precursor chemicals used to manufacture MDMA. The availability of legal alternatives to MDMA such as mephedrone, or methylone, is also thought to have contributed to its decrease in popularity.[144]

Legal status [link]

MDMA is legally controlled in most of the world under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and other international agreements, although exceptions exist for research. In general, the unlicensed use, sale or manufacture of MDMA are all criminal offenses.

United Kingdom [link]

MDMA was made illegal in 1977 by a modification order to the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Although MDMA was not named explicitly in this legislation, the order extended the definition of Class A drugs to include various ring-substituted phenethylamines,[145] thereby making it illegal to sell, buy, or possess the drug without a license. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking. See list of drugs illegal in the UK for more information. In February 2009 an official independent scientific advisory board to the UK government recommended that MDMA be re-classified to Class B, but this recommendation was immediately rejected by the government (see Recommendation to downgrade MDMA). This 2009 report on MDMA stated:[146]

The original classification of MDMA in 1977 under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 as a Class A drug was carried out before it had become widely used and with limited knowledge of its pharmacology and toxicology. Since then use has increased enormously, despite it being a Class A drug. As a consequence, there is now much more evidence on which to base future policy decisions.... Recommendation 1: A harm minimisation approach to the widespread use of MDMA should be continued.... Recommendation 6: MDMA should be re-classified as a Class B drug.

In 2000, the UK Police Foundation issued the Runciman Report, which reviewed the medical and social harms of MDMA and recommended: "Ecstasy and related compounds should be transferred from Class A to Class B."[147] In 2002, the Home Affairs Committee of the UK House of Commons, issued a report, The Government's Drugs Policy: Is it working?, which also recommended that MDMA should be reclassified to a Class B drug.[148] The UK government rejected both recommendations, saying that re-classification of MDMA would not be considered without a recommendation from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the official UK scientific advisory board on drug abuse issues.[149]

In February 2009, the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs issued A review of MDMA ('ecstasy'), its harms and classification under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, which recommended that MDMA be re-classified in the UK from a class A drug to a class B drug.[146]

From the Discussion section of the ACMD report on MDMA:

Physical harms: (10.2) Use of MDMA is undoubtedly harmful. High doses may lead to death: by direct toxicity, in situations of hyperthermia/dehydration, excessive water intake, or for other reasons. However, fatalities are relatively low given its widespread use, and are substantially lower than those due to some other Class A drugs, particularly heroin and cocaine. Although it is no substitute for abstinence, the risks can be minimised by following advice such as drinking appropriate amounts of water (see Annex E). (10.3) Some people experience acute medical consequences as a result of MDMA use, which can lead to hospital admission, sometimes with the requirement for intensive care. MDMA poisonings are not currently increasing in number and are less frequent than episodes due to cocaine. (10.4) MDMA appears not to have a high propensity for dependence or withdrawal reactions, although a number of users seek help through treatment services. (10.5) MDMA appears to have little acute or enduring effect on the mental health of the average user, and, unlike amphetamines and cocaine, it is seldom implicated in significant episodes of paranoia. (10.6) There is at the present time little evidence of longer-term harms to the brain in terms of either its structure or its function. However, there is evidence for some small decline in a variety of domains, including verbal memory, even at low cumulative dose. The magnitude of such deficits appears to be small and their clinical relevance is unclear. The evidence shows that MDMA has been misused in the UK for 20 years, but it should be noted that long-term effects of use cannot be ruled out. (10.7) Overall, the ACMD judges that the physical harms of MDMA more closely equate with those of amphetamine than of heroin or cocaine.

Societal harms: (10.8) MDMA use seems to have few societal effects in terms of intoxication-related harms or social disorder. However, the ACMD notes the very small proportion of cases where ‘ecstasy’ use has been implicated in sexual assault. (10.9) Disinhibition and impulsive, violent or risky behaviours are not commonly seen under the influence of MDMA, unlike with cocaine, amphetamines, heroin and alcohol. (10.10) The major issue for law enforcement is ‘ecstasy's’ position, alongside other Class A drugs, as a commodity favoured by organised criminal groups. It is therefore generally associated with a range of secondary harms connected with the trafficking of illegal drugs.

The UK Home Office rejected the recommendation of its independent scientific advisory board to downgrade MDMA to Class B, "saying it is not prepared to send a message to young people that it takes ecstasy less seriously".[150][151]

The government's veto was criticized in scientific publications. Colin Blakemore, Professor of Neuroscience, Oxford, stated in the British Medical Journal, "The government's decisions compromise its commitment to evidence based policy".[152] Also in response, an editorial in the New Scientist noted "A much larger percentage of people suffer a fatal acute reaction to peanuts than to MDMA.... Sadly, perspective is something that is generally lacking in the long and tortuous debate over illegal drugs."[153]

United States [link]

In the U.S., MDMA was legal and unregulated until 31 May 1985, at which time it was emergency scheduled to DEA Schedule I, for drugs deemed to have no medical uses and a high potential for abuse. During DEA hearings to schedule MDMA, most experts recommended DEA Schedule III prescription status for the drug, due to beneficial usage of MDMA in psychotherapy. The Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) overseeing the hearings, Francis Young, also recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule III. The DEA however classified MDMA as Schedule I.[154][155] However, in Grinspoon v. Drug Enforcement Administration, 828 F.2d 881 (1st Cir. 1987), the First Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the scheduling determination for reconsideration by the DEA.[156] MDMA was temporarily removed from Schedule I.[157] Ultimately, in 1988, the DEA re-evaluated its position on remand and subsequently placed MDMA into Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[158] In 2001, responding to a mandate from the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, resulted in an increase in the penalties for MDMA by nearly 3,000%.[159] The increase in penalties was opposed by the Federation of American Scientists.[160] The increase makes 1 gram of MDMA (four pills at 250 mg per pill's total weight regardless of purity, standard for Federal charges) equivalent to 1 gram of heroin (approximately fifty doses) or 2.2 pounds (1 kg) of cannabis for sentencing purposes at the federal level.[161] See also the RAVE Act of 2003.

World Health Organization [link]

In 1985 the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, despite noting:[162]

No data are available concerning its clinical abuse liability, nature and magnitude of associated public health or social problems.

The decision to recommend scheduling of MDMA was not unanimous:[162]

One member, Professor Paul Grof (Chairman), felt that the decision on the recommendation should be deferred awaiting, in particular, the data on the substance's potential therapeutic usefulness and that at this time international control is not warranted.

The 1971 Convention has a provision in Article 7(a) that allows use of Schedule I drugs for "scientific and very limited medical purposes." The committee's report stated:[162][163]

The Expert Committee held extensive discussions concerning therapeutic usefulness of 3,4 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine. While the Expert Committee found the reports intriguing, it felt that the studies lacked the appropriate methodological design necessary to ascertain the reliability of the observations. There was, however, sufficient interest expressed to recommend that investigations be encouraged to follow up these preliminary findings. To that end, the Expert Committee urged countries to use the provisions of article 7 of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances to facilitate research on this interesting substance.

Environmental concerns [link]

Demand for safrole, a substance used in the manufacture of MDMA, is causing rapid and illicit harvesting of the Cinnamomum parthenoxylon tree in Southeast Asia, in particular the Cardamom Mountains in Cambodia.[164] Demand for safrole, mostly for industrial use but also for MDMA production, depletes around 500,000 trees per year in China, Brazil, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos.[165][better source needed] In 2008 alone, Australian and Cambodian authorities blocked and destroyed the export of 33 tons of safrole, capable of producing 245 million ecstasy tablets; with a street value of 7.6 billion dollars.[166] Only a small proportion of illicitly harvested safrole is going toward MDMA production, as over 90% of the global safrole supply (approx 2000 metric tons per year) is used to manufacture pesticides, fragrances, and other chemicals.[166][167] Sustainable harvesting of safrole is possible from leaves and sticks of certain plants.[166][167]

References [link]

- ^ Stimulants, Narcotics, Hallucinogens – Drugs, Pregnancy, and Lactation., Gerald G. Briggs, OB/GYN News, 1 June 2003.

- ^ "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy)". Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets.. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. https://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/research/job185drugs/methylenedioxymethamphetamine.htm.

- ^ Turner, Amy (4 May 2008). "Ecstasy is the key to treating PTSD". The Times (London). https://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article3850302.ece. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Ecstasy to be tested on terminal cancer patients, Associated Press, 12/28/2004

- ^ Global Commission on Drug Policy, pp. 24, https://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/Report, retrieved 3 March 2012

- ^ "World Drug Report 2010", United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: pp. 15, https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2010/World_Drug_Report_2010_lo-res.pdf, retrieved 27 February 2012

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of psychoactive substance use and dependence.

- ^ Psychedelic Research Worldwide. MAPS. Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ Greer G. Tolbert R. "The Therapeutic Use of MDMA in Ecstasy: The Clinical, Pharmacological, and Neurotoxicological Effects of the Drug MDMA." 1990 (ed Peroutka, SJ) Boston, p. 21-36. (PDF) . Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ Doblin R (2002). "A Clinical Plan for MDMA (Ecstasy) in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA.". J Psychoactive Drugs 34 (2): 185–194. PMID 12691208. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2002/2002_Doblin_20651_2.pdf.

- ^ Sessa B, Nutt DJ. "MDMA, Politics and Medical Research: Have We Thrown the Baby Out With the Bathwater?". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 21 (8): 787–791. DOI:10.1177/0269881107084738. PMID 17984158. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2007/2007_Sessa_22948_1.pdf.

- ^ Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. (1986). "Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting.". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 18 (4): 319–327. PMID 2880946. https://www.heffter.org/pages/subjrep.html.[dead link]

- ^ Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. (1998). "A Method of Conducting Therapeutic Sessions with MDMA.". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 30 (4): 371–379. PMID 9924843. https://www.heffter.org/pages/sessions.html.[dead link]

- ^ Johansen, PO.; Krebs, TS. (2009). "How could MDMA (ecstasy) help anxiety disorders? A neurobiological rationale.". Journal of Psychopharmachology 23 (4): 389–91. DOI:10.1177/0269881109102787. PMID 19273493. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2009/2009_Johansen_23075_1.pdf.

- ^ a b Mithoefer MC; Wagner MT; Mithoefer AT; Jerome I; Doblin R. (2009). "The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study.". Journal of Psychopharmachology 25 (4): 439–52. DOI:10.1177/0269881110378371. PMC 3122379. PMID 20643699. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2010/2010_Mithoefer_23124_1.pdf.

- ^ MDMA and Religion. CSP. Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008) (PDF). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 49. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_64227_EN_EMCDDA_AR08_en.pdf.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008) (PDF). World drug report. United Nations Publications. p. 271. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4. https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf.

- ^ Drugtext – 10 years of ecstasy and other party drug use in Australia: What have we done and what is there left to do?. Drugtext.org. Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ University of Maryland, College Park Center for Substance Abuse Research. "Ecstasy:CESAR". https://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/ecstasy.asp.

- ^ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. May 2000. https://search2.google.cit.nih.gov/search?q=cache:y3dIYYo3lKwJ:www.drugabuse.gov/DirReports/DirRep500/DirectorReport5.html.

- ^ Whetstone, Kobie J. (16 April 2009 – 11 June 2009). "An Analysis of MDMA-Induced Neurotoxicity.". https://mdma.net/kobie/index.html.

- ^ Liechti, ME; Gamma, A; Vollenweider, FX (2001). "Gender Differences in the Subjective Effects of MDMA". Psychopharmacology 154 (2): 161–168. DOI:10.1007/s002130000648. PMID 11314678. https://www.erowid.org/references/refs_view.php?A=ShowDocPartFrame&C=ref&ID=1098&DocPartID=936.

- ^ Erowid (September 2001). Short-Term Side Effects of MDMA.

- ^ Addiction (February 2011). "New study finds no cognitive impairment among ecstasy users".

- ^ McCann, U. D.; Szabo, Z.; Vranesic, M.; Palermo, M.; Mathews, W. B.; Ravert, H. T.; Dannals, R. F.; Ricaurte, G. A. (2008). "Positron emission tomographic studies of brain dopamine and serotonin transporters in abstinent 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy") users: relationship to cognitive performance". Psychopharmacology 200: 439-450. DOI:10.1007/s00213-008-1218-4.

- ^ a b c d "Ecstasy". health.rutgers.edu. https://health.rutgers.edu/brochures/ecstacy.htm. Retrieved 25 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "Ecstasy basics". betweenthelines.net.au. https://www.betweenthelines.net.au/drug-facts/ecstasy-basics. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Ecstasy". communitybuilders.nsw.gov.au. NSW Department of Health. https://www.communitybuilders.nsw.gov.au/download/ecstasy.pdf. Retrieved 25 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c "Ecstasy: effects on the body". ydr.com.au. https://www.mydr.com.au/addictions/ecstasy-effects-on-the-body. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c "Ecstasy". betterhealth.vic.gov.au. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Ecstasy. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "MDMA Basics". erowid.org. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/mdma/mdma_basics.shtml. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Arrue A, Gomez FM, Giralt MT (April 2004). "Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ('Ecstasy') on the jaw-opening reflex". mdma.net. https://www.mdma.net/bruxism/index.html. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "What Is Bruxism?". bruxism.org.uk. https://www.bruxism.org.uk/what-is-bruxism.php. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Molly Flannagan, Ecstasy: Neurotoxicity and How It Can Be Reduced, 2001

- ^ Peroutka SJ, Newman H, Harris H (1988). "Subjective effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in recreational users". Neuropsychopharmacology 1 (4): 273–277. PMID 2908020.

- ^ Chummun H, Tilley V, Ibe J (2010). "3,4-methylenedioxyamfetamine (ecstasy) use reduces cognition". Br J Nurs 19 (2): 94–100. PMID 20235382.

- ^ de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J (2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Ther Drug Monit 26 (2): 137–144. DOI:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

- ^ Bassi S, Rittoo D (2005). "Ecstacy and chest pain due to coronary artery spasm". Int J Cardiol 99 (3): 485–487. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.057. PMID 15771938.

- ^ Woodrow G, Turney JH (1999). "Ecstasy-induced renal vasculitis". Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 798.

- ^ Badon LA, Hicks A, Lord K, Ogden BA, Meleg-Smith S, Varner KJ (2002). "Changes in cardiovascular responsiveness and cardiotoxicity elicited during binge administration of Ecstasy". J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302 (3): 898–907. DOI:10.1124/jpet.302.3.898. PMID 12183645.

- ^ Tiangco DA, Halcomb S, Lattanzio FA, Jr., Hargrave BY (2010). "3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine alters left ventricular function and activates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) in a time and dose dependent manner". Int J Mol Sci 11 (12): 4843–4863. DOI:10.3390/ijms11124743.

- ^ Mende L, Böhm R, Regenthal R, Klein N, Grond S, Radke J (2005). "Cardiac arrest caused by an ecstasy intoxication". Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 40 (12): 762–765. DOI:10.1055/s-2005-870500. PMID 16362878.

- ^ Qasim A, Townend J, Davies MK (2001). "Ecstasy induced acute myocardial infarction". Heart 85 (6): E10. DOI:10.1136/heart.85.6.e10. PMC 1729787. PMID 11359764. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1729787.

- ^ Auer J, Berent R, Weber T, Lassnig E, Eber B (2002). "Subarachnoid haemorrhage with "Ecstasy" abuse in a young adult". Neurol Sci 23 (4): 199–201. DOI:10.1007/s100720200062. PMID 12536290.

- ^ Manchanda S, Connolly MJ (1993). "Cerebral infarction in association with Ecstasy abuse". Postgrad Med J 69 (817): 874–875. DOI:10.1136/pgmj.69.817.874. PMC 2399908. PMID 7904748. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2399908.

- ^ Crean RD, Davis SA, Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Katner SN, Taffe MA (2006). "Effects of (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine and methamphetamine on temperature and activity in rhesus macaques". Neuroscience 142 (2): 515–525. DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.033. PMC 1853374. PMID 16876329. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1853374.

- ^ Sharma HS, Ali SF (2008). "Acute administration of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine induces profound hyperthermia, blood–brain barrier disruption, brain edema formation, and cell injury". Ann N Y Acad Sci 1139: 242–258. DOI:10.1196/annals.1432.052. PMID 18991870.

- ^ Verheyden SL, Henry JA, Curran HV (2003). "Acute, sub-acute and long-term subjective consequences of 'ecstasy' (MDMA) consumption in 430 regular users". Hum Psychopharmacol 18 (7): 507–17. DOI:10.1002/hup.529. PMID 14533132.

- ^ Verheyden SL, Maidment R, Curran HV (2003). "Quitting ecstasy: an investigation of why people stop taking the drug and their subsequent mental health". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 17 (4): 371–8. DOI:10.1177/0269881103174014. PMID 14870948.

- ^ Laws KR, Kokkalis J (2007). "Ecstasy (MDMA) and memory function: a meta-analytic update". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 22 (6): 381–88. DOI:10.1002/hup.857.

- ^ Rodgers J, Buchanan T, Scholey AB, Heffernan TM, Ling J, Parrott AC (2003). "Patterns of drug use and the influence of gender on self-reports of memory ability in ecstasy users: a web-based study". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 17 (4): 389–96. DOI:10.1177/0269881103174016. PMID 14870950.

- ^ Halpern, J. H., Sherwood, A. R., Hudson, J. I., Gruber, S., Kozin, D., Pope Jr, H. G. (2011). "Residual neurocognitive features of long-term ecstasy users with minimal exposure to other drugs". Addiction 106 (4): 777–786. DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03252.x. PMC 3053129. PMID 21205042. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3053129.

- ^ Jones AL, Simpson KJ (1999). "Review article: mechanisms and management of hepatotoxicity in ecstasy (MDMA) and amphetamine intoxications" (PDF). Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 13 (2): 129–33. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00454.x. PMID 10102941. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1999/1999_jones_16_1.pdf.

- ^ Milosevic A, Agrawal N, Redfearn P, Mair L (1999). "The occurrence of toothwear in users of Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine)" (PDF). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 27 (4): 283–7. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02022.x. PMID 10403088. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1999/1999_milosevic_84_1.pdf.

- ^ Creighton FJ, Black DL, Hyde CE (1991). "'Ecstasy' psychosis and flashbacks" (PDF). Br J Psychiatry 159 (5): 713–5. DOI:10.1192/bjp.159.5.713. PMID 1684523. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1991/1991_creighton_526_1.pdf.

- ^ "Drug Toxicity". Web.cgu.edu. https://web.cgu.edu/faculty/gabler/drug_toxicity.htm. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet 369 (9566): 1047–53. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ^ Nimmo SM, Kennedy BW, Tullett WM, Blyth AS, Dougall JR (1993). "Drug-induced hyperthermia". Anaesthesia 48 (10): 892–5. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07423.x. PMID 7902026.

- ^ Malberg JE, Seiden LS (1998). "Small changes in ambient temperature cause large changes in 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced serotonin neurotoxicity and core body temperature in the rat". J. Neurosci. 18 (13): 5086–94. PMID 9634574.

- ^ Wolff K, Tsapakis EM, Winstock AR, et al. (2006). "Vasopressin and oxytocin secretion in response to the consumption of ecstasy in a clubbing population". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 20 (3): 400–10. DOI:10.1177/0269881106061514. PMID 16574714.

- ^ Fischer C, Hatzidimitriou G, Wlos J, Katz J, Ricaurte G (1995). "Reorganization of ascending 5-HT axon projections in animals previously exposed to the recreational drug (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy")". J. Neurosci. 15 (8): 5476–85. PMID 7643196.

- ^ Scheffel U, Szabo Z, Mathews WB, et al. (1998). "In vivo detection of short- and long-term MDMA neurotoxicity—a positron emission tomography study in the living baboon brain". Synapse 29 (2): 183–92. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<183::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2–3. PMID 9593108. https://www.erowid.org/references/refs_view.php?ID=367.

- ^ a b Reneman L, Lavalaye J, Schmand B, et al. (2001). "Cortical serotonin transporter density and verbal memory in individuals who stopped using 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or "ecstasy"): preliminary findings". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58 (10): 901–6. DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.901. PMID 11576026.

- ^ Neurotoxicity at Dancesafe.org

- ^ Does MDMA Cause Brain Damage?, Matthew Baggott, and John Mendelson

- ^ Research on Ecstasy Is Clouded by Errors, Donald G. McNeil Jr., New York Times, 2 December 2003.

- ^ Depression at DanceSafe.org

- ^ Wareing, M. and Fisk, J.E. and Murphy, P.N. (2000). "Working memory deficits in current and previous users of MDMA (‘ecstasy’)" (PDF). Br J Psychol 91 (Pt 2): 181–8. DOI:10.1348/000712600161772. PMID 10832513. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/mdma/references/journal/2000_wareing_brit-psychology_1/2000_wareing_brit-psychology_1_text.pdf.

- ^ Study claims recreational ecstasy use and depression unrelated, Wikinews, 26 April 2006

- ^ Guillot C, Greenway D (2006). "Recreational ecstasy use and depression". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 20 (3): 411–6. DOI:10.1177/0269881106063265. PMID 16574715. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2007/2007_Guillot_22900_1.pdf.

- ^ Ecstasy Study Botched, Retracted, Kristen Philipkoski, Wired.com, 09.05.03

- ^ McCann UD, Ricaurte GA (2001). "Caveat emptor: editors beware" (PDF). Neuropsychopharmacology 24 (3): 333–6. DOI:10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00171-8. PMID 11256359. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2001/2001_mccann_1129_1.pdf.

- ^ Green AR, Mechan AO, Elliott JM, O'Shea E, Colado MI (2003). "The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy")". Pharmacol. Rev. 55 (3): 463–508. DOI:10.1124/pr.55.3.3. PMID 12869661.

- ^ Zakzanis KK, Campbell Z, Jovanovski D (2007). "The neuropsychology of ecstasy (MDMA) use: a quantitative review". Hum Psychopharmacol 22 (7): 427–35. DOI:10.1002/hup.873. PMID 17896346.

- ^ Gijsman HJ, Verkes RJ, van Gerven JM, Cohen AF (1999). "MDMA study" (PDF). Neuropsychopharmacology 21 (4): 597. DOI:10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00021-4. PMID 10481843. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1999/1999_gijsman_295_1.pdf.

- ^ Kish, SJ (2002). "How strong is the evidence that brain serotonin neurons are damaged in human users of ecstasy?". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71 (4): 845–55. DOI:10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00708-0. PMID 11888575.

- ^ Kish SJ (2003). "What is the evidence that Ecstasy (MDMA) can cause Parkinson's disease?" (PDF). Mov. Disord. 18 (11): 1219–23. DOI:10.1002/mds.10643. PMID 14639660. https://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2003/2003_kish_6239_1.pdf.

- ^ Aghajanian & Liebermann (2001) 'Caveat Emptor: Reseearchers Beware' Neuropsychopharmacology 24,3:335–6

- ^ McCann, Una D.; Ricaurte, George A. (1991). "Major metabolites of(±)3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) do not mediate its toxic effects on brain serotonin neurons". Brain Research 545 (1–2): 279–282. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(91)91297-E. PMID 1860050.

- ^ Miller, RT; Lau, SS; Monks, TJ (1997). "2,5-Bis-(glutathion-S-yl)-alpha-methyldopamine, a putative metabolite of (+/-)-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, decreases brain serotonin concentrations". Eur J Pharmacol. 323 (2–3): 173–80. DOI:10.1016/S0014-2999(97)00044-7. PMID 9128836.

- ^ Conway, EL; Louis, WJ; Jarrot, B. (1978). "Acute and chronic administration of alpha-methyldopa: regional levels of endogenous and alpha-methylated catecholamines in rat brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 52 (3–4): 271–80. DOI:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90279-0. PMID 729639.

- ^ https://ecstasydata.org/datastats.php?row=Summary&percent=1

- ^ Refstad S (2003). "Paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA) poisoning; a 'party drug' with lethal effects". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 47 (10): 1298–9. DOI:10.1046/j.1399-6576.2003.00245.x. PMID 14616331.

- ^ Lamberth PG, Ding GK, Nurmi LA (2008). "Fatal paramethoxy-amphetamine (PMA) poisoning in the Australian Capital Territory". Med. J. Aust. 188 (7): 426. PMID 18393753.

- ^ J Pharm Pharmacol. 1980 Apr;32(4):262-6.

- ^ Scientists want new drug rankings, BBC News, 23 March 2007

- ^ a b Nutt DJ (2009). "Equasy-- an overlooked addiction with implications for the current debate on drug harms". J Psychopharmacol 23 (1): 3–5. DOI:10.1177/0269881108099672. PMID 19158127. https://www.encod.org/info/EQUASY-A-HARMFUL-ADDICTION.html.

- ^ Horizon (2008) Britain's most dangerous drugs. Tuesday 5 February 2008, 9pm, BBC Two.

- ^ Forsyth, A (1). "Distorted? a quantitative exploration of drug fatality reports in the popular press". International Journal of Drug Policy 12 (5–6): 435–453. DOI:10.1016/S0955-3959(01)00092-5.

- ^ Ecstasy 'not worse than riding', BBC News, 7 February 2009

- ^ Halpern et. al, Addiction, 2011

- ^ Qualitative review of serotonin syndrome, ecstasy (MDMA) and the use of other serotonergic substances: hierarchy of risk (by Silins E, Copeland J, Dillon P.)

- ^ Vuori E, Henry JA, Ojanperä I, et al. (2003). "Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide". Addiction 98 (3): 365–8. DOI:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00292.x. PMID 12603236. https://www.mdma.net/toxicity/moclobemide.html.

- ^ The Prozac Misunderstanding, at TheDEA.org

- ^ Milhazes N, Martins P, Uriarte E, et al. (2007). "Electrochemical and spectroscopic characterisation of amphetamine-like drugs: application to the screening of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and its synthetic precursors". Anal. Chim. Acta 596 (2): 231–41. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2007.06.027. PMID 17631101.

- ^ Milhazes N, Cunha-Oliveira T, Martins P, et al. (2006). "Synthesis and cytotoxic profile of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy") and its metabolites on undifferentiated PC12 cells: A putative structure-toxicity relationship". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19 (10): 1294–304. DOI:10.1021/tx060123i. PMID 17040098.

- ^ Reductive aminations of carbonyl compounds with borohydride and borane reducing agents. Baxter, Ellen W.; Reitz, Allen B. Organic Reactions (Hoboken, New Jersey, United States) (2002), 59.

- ^ Gimeno P, Besacier F, Bottex M, Dujourdy L, Chaudron-Thozet H (2005). "A study of impurities in intermediates and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) samples produced via reductive amination routes". Forensic Sci. Int. 155 (2–3): 141–57. DOI:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.11.013. PMID 16226151.

- ^ Nov 2005 DEA Microgram newsletter. Usdoj.gov (11 November 2005). Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald JL, Reid JJ (1990). "Effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine on the release of monoamines from rat brain slices". European Journal of Pharmacology 191 (2): 217–20. DOI:10.1016/0014-2999(90)94150-V. PMID 1982265.

- ^ Bogen IL, Haug KH, Myhre O, Fonnum F (2003). "Short- and long-term effects of MDMA ("ecstasy") on synaptosomal and vesicular uptake of neurotransmitters in vitro and ex vivo". Neurochemistry International 43 (4–5): 393–400. DOI:10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00027-5. PMID 12742084.

- ^ Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR (2007). "New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 47: 681–98. DOI:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. PMID 17209801.

- ^ a b Bunzow, J. R.; Sonders, M. S.; Arttamangkul, S.; Harrison, L. M.; Zhang, G.; Quigley, D. I.; Darland, T.; Suchland, K. L. et al. (2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Molecular Pharmacology 60 (6): 1181–1188. PMID 11723224.

- ^ Nation, Sober. "Stimulant Abuse among College Students". Recovery Resources. Sober Nation. https://www.sobernation.com/stimulant-abuse-with-college-students/. Retrieved 12/7/11.

- ^ Borowsky, B.; Adham, N.; Jones, K. A.; Raddatz, R.; Artymyshyn, R.; Ogozalek, K. L.; Durkin, M. M.; Lakhlani, P. P. et al. (2001). "Trace amines: Identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (16): 8966–8971. DOI:10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMC 55357. PMID 11459929. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=55357.

- ^ Xie, Z.; Westmoreland, S. V.; Miller, G. M. (2008). "Modulation of Monoamine Transporters by Common Biogenic Amines via Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 and Monoamine Autoreceptors in Human Embryonic Kidney 293 Cells and Brain Synaptosomes". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 325 (2): 629–640. DOI:10.1124/jpet.107.135079. PMID 18310473.