| Phenol | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phenol |

|

|

Other names

Carbolic Acid, Benzenol, Phenylic Acid, Hydroxybenzene, Phenic acid |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 108-95-2 |

| PubChem | 996 |

| ChemSpider | 971 |

| UNII | 339NCG44TV |

| DrugBank | DB03255 |

| KEGG | D06536 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15882 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL14060 |

| RTECS number | SJ3325000 |

| ATC code | C05,D08AE03, N01BX03, R02AA19 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C6H6O |

| Molar mass | 94.11 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | transparent crystalline solid |

| Density | 1.07 g/cm3 |

| Melting point |

40.5 °C, 314 K, 105 °F |

| Boiling point |

181.7 °C, 455 K, 359 °F |

| Solubility in water | 8.3 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.95 (in water), 29.1 (in acetonitrile)[2] |

| λmax | 270.75 nm[1] |

| Dipole moment | 1.7 D |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |    [3] [3] |

| GHS hazard statements | H301, H311, H314, H331, H341, H373[3] |

| GHS precautionary statements | P261, P280, P301+310, P305+351+338, P310[3] |

| EU classification | Toxic (T) Muta. Cat. 3 Corrosive (C) |

| R-phrases | R23/R24/R25-R34-R48/R20/R21/R22-R68 |

| S-phrases | (S1/2)-S24/S25-S26-S28-S36/S37/S39-S45 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 79 °C |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds | Benzenethiol |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

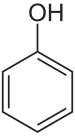

Phenol, also known as carbolic acid and phenic acid, is an organic compound with the chemical formula C6H5OH. It is a white crystalline solid at room temperature. The molecule consists of a phenyl group (-C6H5) bonded to a hydroxyl group (-OH). It is mildly acidic, but requires careful handling due to its propensity to cause burns.

Phenol was first extracted from coal tar, but today is produced on a large scale (about 7 billion kg/year) using industrial processes. It is an important industrial commodity as a precursor to many materials and useful compounds.[4] Its major uses involve its conversion to plastics or related materials. Phenol and its chemical derivatives are key for building polycarbonates, epoxies, Bakelite, nylon, detergents and a large collection of drugs and herbicides.

Contents |

Properties [link]

Phenol is appreciably soluble in water, with about 8.3 g dissolving in 100 mL (0.88 M). Homogeneous mixtures of phenol and water at phenol to water mass ratios of ~2.6 and higher are also possible. The sodium salt of phenol, sodium phenoxide, is far more water soluble.

Acidity [link]

It is slightly acidic: the phenol molecules have weak tendencies to lose the H+ ion from the hydroxyl group, resulting in the highly water-soluble phenolate anion C6H5O− (also called phenoxide).[5] Compared to aliphatic alcohols, phenol is about 1 million times more acidic, although it is still considered a weak acid. It reacts completely with aqueous NaOH to lose H+, whereas most alcohols react only partially. Phenols are less acidic than carboxylic acids, and even carbonic acid.

One explanation for the increased acidity over alcohols is resonance stabilization of the phenoxide anion by the aromatic ring. In this way, the negative charge on oxygen is shared by the ortho and para carbon atoms.[6] In another explanation, increased acidity is the result of orbital overlap between the oxygen's lone pairs and the aromatic system.[7] In a third, the dominant effect is the induction from the sp2 hybridised carbons; the comparatively more powerful inductive withdrawal of electron density that is provided by the sp2 system compared to an sp3 system allows for great stabilization of the oxyanion.

In making this conclusion, one can examine the pKa of the enol of acetone, which is 19.0, in comparison to phenol with a pKa of 10.0.[8] However, this similarity of acidities of phenol and acetone enol is not observed in the gas phase, and is because the difference of solvation energies of the deprotonated acetone enol and phenoxide almost exactly offsets the experimentally observed gas phase acidity difference. It has recently been shown that only about 1/3 of the increased acidity of phenol is due to inductive effects, with resonance accounting for the rest.[9]

Phenoxide anion [link]

Phenol can be deprotonated with moderate base such as triethylamine, forming the nucleophilic phenoxide anion or phenolate anion, which is highly water-soluble.

The phenoxide anion has a similar nucleophilicity to free amines, with the further advantage that its conjugate acid (neutral phenol) does not become entirely deactivated as a nucleophile even in moderately acidic conditions. Phenols are sometimes used in peptide synthesis to "activate" carboxylic acids or esters to form activated esters. Phenolate esters are far more stable than acid anhydrides or acyl halides but are sufficiently reactive under mild conditions to facilitate the formation of amide bonds.

Phenoxides are enolates stabilised by aromaticity. Under normal circumstances, phenoxide is more reactive at the oxygen position, but the oxygen position is a "hard" nucleophile whereas the alpha-carbon positions tend to be "soft".[10]

Tautomerism [link]

Phenol exhibits keto-enol tautomerism with its unstable keto tautomer cyclohexadienone, but only a tiny fraction of phenol exists as the keto form. The equilibrium constant for enolisation is approximately 10−13, meaning that only one in every ten trillion molecules is in the keto form at any moment.[11] The small amount of stabilisation gained by exchanging a C=C bond for a C=O bond is more than offset by the large destabilisation resulting from the loss of aromaticity. Phenol therefore exists entirely in the enol form.[12]

Reactions [link]

Phenol is highly reactive toward electrophilic aromatic substitution as the oxygen atom's pi electrons donate electron density into the ring. By this general approach, many groups can be appended to the ring, via halogenation, acylation, sulfonation, and other processes. However, phenol's ring is so strongly activated — second only to aniline - that bromination or chlorination of phenol leads to substitution on all carbons ortho and para to the hydroxy group, not only on one carbon.

Production [link]

Because of phenol's commercial importance, many methods have been developed for its production. The dominant current route, accounting for 95% of production (2003), involves the partial oxidation of cumene (isopropylbenzene) via the Hock rearrangement:[4]

- C6H5CH(CH3)2 + O2 → C6H5OH + (CH3)2CO

Compared to most other processes, the cumene-hydroperoxide process uses relatively mild synthesis conditions, and relatively inexpensive raw materials. However, to operate economically, there must be demand for both phenol, and the acetone by-product.

An early commercial route, developed by Bayer and Monsanto in the early 1900s, begins with the reaction of a strong base with benzenesulfonate[13]:

- C6H5SO3H + 2 NaOH → C6H5OH + Na2SO3 + H2O

Other methods under consideration involve:

- hydrolysis of chlorobenzene, using base or steam (Raschig-Hooker process)[14]:

- C6H5Cl + H2O → C6H5OH + HCl

- direct oxidation of benzene with nitrous oxide, a potentially "green" process:

- C6H6 + N2O → C6H5OH + N2

- oxidation of toluene, as developed by Dow Chemical:

- C6H5CH3 + 2 O2 → C6H5OH + CO2 + H2O

In the Lummus Process, the oxidation of toluene to benzoic acid is conducted separately.

Phenol is also a recoverable byproduct of coal pyrolysis[14].

Uses [link]

The major uses of phenol, consuming two thirds of its production, involve its conversion to plastics or related materials. Condensation with acetone gives bisphenol-A, a key precursor to polycarbonates and epoxide resins. Condensation of phenol, alkylphenols, or diphenols with formaldehyde gives phenolic resins, a famous example of which is Bakelite. Hydrogenation of phenol gives cyclohexanone, a precursor to nylon. Nonionic detergents are produced by alkylation of phenol to give the alkylphenols, e.g., nonylphenol, which are then subjected to ethoxylation.[4]

Phenol is also a versatile precursor to a large collection of drugs, most notably aspirin but also many herbicides and pharmaceuticals. Phenol is also used as an oral anesthetic/analgesic in products such as Chloraseptic or other brand name and generic equivalents, commonly used to temporarily treat pharyngitis.

Niche uses [link]

Phenol is so inexpensive that it attracts many small-scale uses. It once was widely used as an antiseptic, especially as Carbolic soap, from the early 1900s through the 1970s. It is a component of industrial paint strippers used in the aviation industry for the removal of epoxy, polyurethane and other chemically resistant coatings.[15]

Phenol derivatives are also used in the preparation of cosmetics including sunscreens,[16] hair dyes, and skin lightening preparations.[17]

History [link]

Phenol was discovered in 1834 by Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge who extracted it from coal tar. Coal tar remained the primary source until the development of the petrochemical industry.

The antiseptic properties of phenol were used by Sir Joseph Lister (1827–1912) in his pioneering technique of antiseptic surgery. Lister decided that the wounds themselves had to be thoroughly cleaned. He then covered the wounds with a piece of rag or lint[18] covered in phenol, or carbolic acid as he called it. The skin irritation caused by continual exposure to phenol eventually led to the substitution of aseptic (germ-free) techniques in surgery.

Phenol is the active ingredient in some oral analgesics such as Chloraseptic spray and Carmex.

Phenol was the main ingredient of the Carbolic Smoke Ball, an ineffective device marketed in London in the 19th century as protecting against influenza and other ailments, and the subject of the famous law case Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company.

Second World War [link]

Injections of phenol have occasionally been used as a means of execution. In particular, phenol and cyanide injections were used as a means of individual execution by the Nazis during the Second World War.[19] Originally used by the Nazis in 1939 as part of Action T4, phenol,[20] inexpensive, easy to make and quickly lethal, became the injectable toxin of choice as part of Nazi Germany's "euthanasia" program.[20][19][21] Although Zyklon-B pellets, invented by Gerhard Lenz, were used in the gas chambers to exterminate large groups of people, the Nazis learned that extermination of smaller groups was more economical via injection of each victim, one at a time, with phenol. Phenol injections were given to thousands of people in concentration camps, especially at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Approximately one gram is enough to cause death.[22] Injections were administered by medical doctors, their assistants, or sometimes prisoner doctors; such injections were originally given intravenously, more commonly in the arm, but injection directly into the heart, so as to induce nearly instant death, was later adopted.[23] One of the best known inmates to be executed with a phenol injection in Auschwitz was St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Catholic priest who volunteered to undergo three weeks of starvation and dehydration in the place of another inmate.[23]

Natural occurrences [link]

Temporal glands secretion examination showed the presence of phenol and 4-methyl phenol during musth in male elephants.[24][25]

Occurrence in whisky [link]

Phenol is a measurable component in the aroma and taste of the distinctive Islay scotch whisky,[26] generally ~30, but up to over 150[27] ppm in the malted barley used to produce whisky.

Biodegradation [link]

Cryptanaerobacter phenolicus is a bacterium species that produces benzoate from phenol via 4-hydroxybenzoate.[28] Rhodococcus phenolicus is a bacterium species able to degrade phenol as sole carbon sources.[29]

Toxicity [link]

Phenol is a strong neurotoxin, if injected in blood-streams it can lead to instant death as it shuts down the neural transmissions system. Phenol and its vapors are corrosive to the eyes, the skin, and the respiratory tract.[30] Repeated or prolonged skin contact with phenol may cause dermatitis, or even second and third-degree burns due to phenol's caustic and defatting properties.[31] Inhalation of phenol vapor may cause lung edema.[30] The substance may cause harmful effects on the central nervous system and heart, resulting in dysrhythmia, seizures, and coma.[32] The kidneys may be affected as well. Exposure may result in death and the effects may be delayed. Long-term or repeated exposure of the substance may have harmful effects on the liver and kidneys."[33] There is no evidence that phenol causes cancer in humans.[34] Besides its hydrophobic effects, another mechanism for the toxicity of phenol may be the formation of phenoxyl radicals.[35]

Chemical burns from skin exposures can be decontaminated by washing with polyethylene glycol,[36] isopropyl alcohol,[37] or perhaps even copious amounts of water.[38] Removal of contaminated clothing is required, as well as immediate hospital treatment for large splashes. This is particularly important if the phenol is mixed with chloroform (a commonly-used mixture in molecular biology for DNA & RNA purification from proteins).

Phenols [link]

The word phenol is also used to refer to any compound that contains a six-membered aromatic ring, bonded directly to a hydroxyl group (-OH). Thus, phenols are a class of organic compounds of which the phenol discussed in this article is the simplest member.

See also [link]

References [link]

- ^ https://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/PhotochemCAD/html/phenol.html

- ^ Kütt, A.; Movchun, V.; Rodima, T.; Dansauer, T.; Rusanov, E. B.; Leito, I.; Kaljurand, I.; Koppel, J.; Pihl, V.; Koppel, I.; Ovsjannikov, G.; Toom, L.; Mishima, M.; Medebielle, M.; Lork, E.; Röschenthaler, G.-V.; Koppel, I. A.; Kolomeitsev, A. A. Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl, a Sterically Crowded and Electron-withdrawing Group: Synthesis and Acidity of Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)benzene, -toluene, -phenol, and -aniline. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2607-2620. doi:10.1021/jo702513w

- ^ a b c Online Sigma Catalogue , accessdate: June 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c Manfred Weber, Markus Weber, Michael Kleine-Boymann "Phenol" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2004, Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_299.pub2.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-72091-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=JDR-nZpojeEC&printsec=frontcover

- ^ Organic Chemistry 2nd Ed. John McMurry ISBN 0-534-07968-7

- ^ "The Acidity of Phenol". ChemGuide. Jim Clark. https://www.chemguide.co.uk/organicprops/phenol/acidity.html. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ For further reading on the fine points of this topic, see David A. Evans's explanation.

- ^ Pedro J. Silva (2009). "Inductive and Resonance Effects on the Acidities of Phenol, Enols, and Carbonyl α-Hydrogens.". J. Org. Chem. 74 (2): 914–916. DOI:10.1021/jo8018736. PMID 19053615.(Solvation effects on the relative acidities of acetaldehyde enol and phenol described in the Supporting Information)

- ^ David Y. Curtin and Allan R. Stein (1966). "2,6,6-Trimethyl-2,4-Cyclohexadione.". Organic Syntheses 46: 115. https://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/prep.asp?prep=cv5p1092.

- ^ Capponi, Marco; Gut, Ivo G.; Hellrung, Bruno; Persy, Gaby; Wirz, Jakob (1999). "Ketonization equilibria of phenol in aqueous solution". Can. J. Chem. 77: 605–613. DOI:10.1139/cjc-77-5-6-605.

- ^ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- ^ Wittcoff, H.A., Reuben, B.G. Industrial Organic Chemicals in Perspective. Part One: Raw Materials and Manufacture. Wiley-Interscience, New York. 1980.

- ^ a b Franck, H.-G., Stadelhofer, J.W. Industrial Aromatic Chemistry. Springer-Verlag, New York. 1988. pp. 148-155.

- ^ "CH207 Aircraft paintstripper, phenolic, acid". Callington. 14 October 2009. https://www.callingtonhaven.com/_assets/ch207.pdf. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ A. Svobodová*, J. Psotová, and D. Walterová (2003). "Natural Phenolics in the Prevention of UV-Induced Skin Damage. A Review". Biomed. Papers 147 (2): 137–145.

- ^ DeSelms, R. H.; UV-Active Phenol Ester Compounds; Enigen Science Publishing: Washington, DC, 2008.

- ^ Lister, Joseph (1867). "Antiseptic Principle Of The Practice Of Surgery". https://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1867lister.html.

- ^ a b The Experiments by Peter Tyson. NOVA

- ^ a b The Nazi Doctors, Chapter 14, Killing with Syringes: Phenol Injections. By Dr. Robert Jay Lifton

- ^ Euthanasia Program: Holocaust Encyclopedia

- ^ "Phenol: Hazards and Precautions". University of Connecticut, USA. https://www.ehs.uconn.edu/Word%20Docs/Phenol%20Hazards%20and%20Precautions.pdf. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ^ a b "Killing through phenol injection". Auschwitz — FINAL STATION EXTERMINATION. Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria. https://www.wsg-hist.uni-linz.ac.at/AUSCHWITZ/HTML/Phenol.html. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ Physiological Correlates of Musth: Lipid Metabolites and Chemical Composition of Exudates. L.E.L Rasmussen and Thomas E Perrin, Physiology & Behavior, October 1999, Volume 67, Issue 4, Pages 539–549, doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00114-6

- ^ Musth in elephants. Deepa Ananth, Zoo's print journal, 15(5), pages 259-262 (article)

- ^ "Peat, Phenol and PPM, by Dr P. Brossard" (PDF). https://www.whisky-news.com/En/reports/Peat_phenol_ppm.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ^ "Bruichladdich Octomore 4.2 "Comus" Islay Single Malt Whisky". https://www.bruichladdich.com/the-whisky/peated-whisky/octomore/octomore-4-2-comus-167ppm.

- ^ Cryptanaerobacter phenolicus gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobe that transforms phenol into benzoate via 4-hydroxybenzoate. Pierre Juteau, Valérie Côté, Marie-France Duckett, Réjean Beaudet, François Lépine, Richard Villemur and Jean-Guy Bisaillon, IJSEM, January 2005, vol. 55, no. 1, pages 245-250, doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02914-0

- ^ Rhodococcus phenolicus sp. nov., a novel bioprocessor isolated actinomycete with the ability to degrade chlorobenzene, dichlorobenzene and phenol as sole carbon sources. Rehfuss M and Urban J, Syst. Appl. Microbiol. (2005), 28, pages 695-701 (Erratum: Syst. Appl. Microbiol. (2006) 29, page 182), PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2005.05.011

- ^ a b Budavari, S, ed. (1996). The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemical, Drugs, and Biologicals. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck.

- ^ Lin TM, Lee SS, Lai CS, Lin SD (June 2006). "Phenol burn". Burns: Journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries 32 (4): 517–21. DOI:10.1016/j.burns.2005.12.016. PMID 16621299.

- ^ Warner, MA; Harper, JV (1985). "Cardiac dysrhythmias associated with chemical peeling with phenol". Anesthesiology 62 (3): 366–7. DOI:10.1097/00000542-198503000-00030. PMID 2579602.

- ^ World Health Organization/International Labour Organization: International Chemical Safety Cards, https://www.inchem.org/documents/icsc/icsc/eics0070.htm

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. "How can phenol affect my health?". Toxicological Profile for Phenol: 24. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp115.pdf.

- ^ Hanscha, Corwin; McKarnsb, Susan C; Smith, Carr J; Doolittle, David J (June 15, 2000). "Comparative QSAR evidence for a free-radical mechanism of phenol-induced toxicity". Chemico-Biological Interactions 127 (1): 61–72. DOI:10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00171-X. PMID 10903419. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T56-40S0C7X5&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=e39425b7cfcb3432a346b9604aea350e.

- ^ Brown, VKH; Box, VL; Simpson, BJ (1975). "Decontamination procedures for skin exposed to phenolic substances". Archives of Environmental Health 30 (1): 1–6. PMID 1109265.

- ^ Hunter, DM; Timerding, BL; Leonard, RB; McCalmont, TH; Schwartz, E (1992). "Effects of isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, and polyethylene glycol/industrial methylated spirits in the treatment of acute phenol burns". Annals of Emergency Medicine 21 (11): 1303–7. DOI:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81891-8.

- ^ Pullin, TG; Pinkerton, MN; Johnson, RV; Kilian, DJ (1978). "Decontamination of the skin of swine following phenol exposure: a comparison of the relative efficacy of water versus polyethylene glycol/industrial methylated spirits". Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 43 (1): 199–206. DOI:10.1016/S0041-008X(78)80044-1. PMID 625760.

External links [link]

| Look up phenol in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- International Chemical Safety Card 0070

- Phenol Material Safety Data Sheet

- National Pollutant Inventory: Phenol Fact Sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- IARC Monograph: "Phenol"

- Arcane Radio Trivia outlines competing uses for Phenol circa 1915

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

https://wn.com/Phenol

Phenolic content in wine

The phenolic content in wine refers to the phenolic compounds—natural phenol and polyphenols—in wine, which include a large group of several hundred chemical compounds that affect the taste, color and mouthfeel of wine. These compounds include phenolic acids, stilbenoids, flavonols, dihydroflavonols, anthocyanins, flavanol monomers (catechins) and flavanol polymers (proanthocyanidins). This large group of natural phenols can be broadly separated into two categories, flavonoids and non-flavonoids. Flavonoids include the anthocyanins and tannins which contribute to the color and mouthfeel of the wine. The non-flavonoids include the stilbenoids such as resveratrol and phenolic acids such as benzoic, caffeic and cinnamic acids.

Origin of the phenolic compounds

The natural phenols are not evenly distributed within the fruit. Phenolic acids are largely present in the pulp, anthocyanins and stilbenoids in the skin, and other phenols (catechins, proanthocyanidins and flavonols) in the skin and the seeds. During the growth cycle of the grapevine, sunlight will increase the concentration of phenolics in the grape berries, their development being an important component of canopy management. The proportion of the different phenols in any one wine will therefore vary according to the type of vinification. Red wine will be richer in phenols abundant in the skin and seeds, such as anthocyanin, proanthocyanidins and flavonols, whereas the phenols in white wine will essentially originate from the pulp, and these will be the phenolic acids together with lower amounts of catechins and stilbenes. Red wines will also have the phenols found in white wines.