How Romans Viewed the Greeks: From Conquest to Cultural Fusion

The relationship between Romans and Greeks was complex, shaped by admiration, imitation, and a degree of tension.

Romans were conflicted in their view of the Greeks. They respected Greek achievements and were wary of adopting too much from a culture they had conquered, but could not help but admire. This dynamic created a cultural interplay that helped shape the identity of Roman civilization.

Some Romans embraced Greek culture enthusiastically. These "Hellenophiles" believed that Greece's cultural achievements were to be revered and incorporated into Roman life. The orator Cicero, poet Virgil, and emperors like Hadrian were admirers of Greek culture.

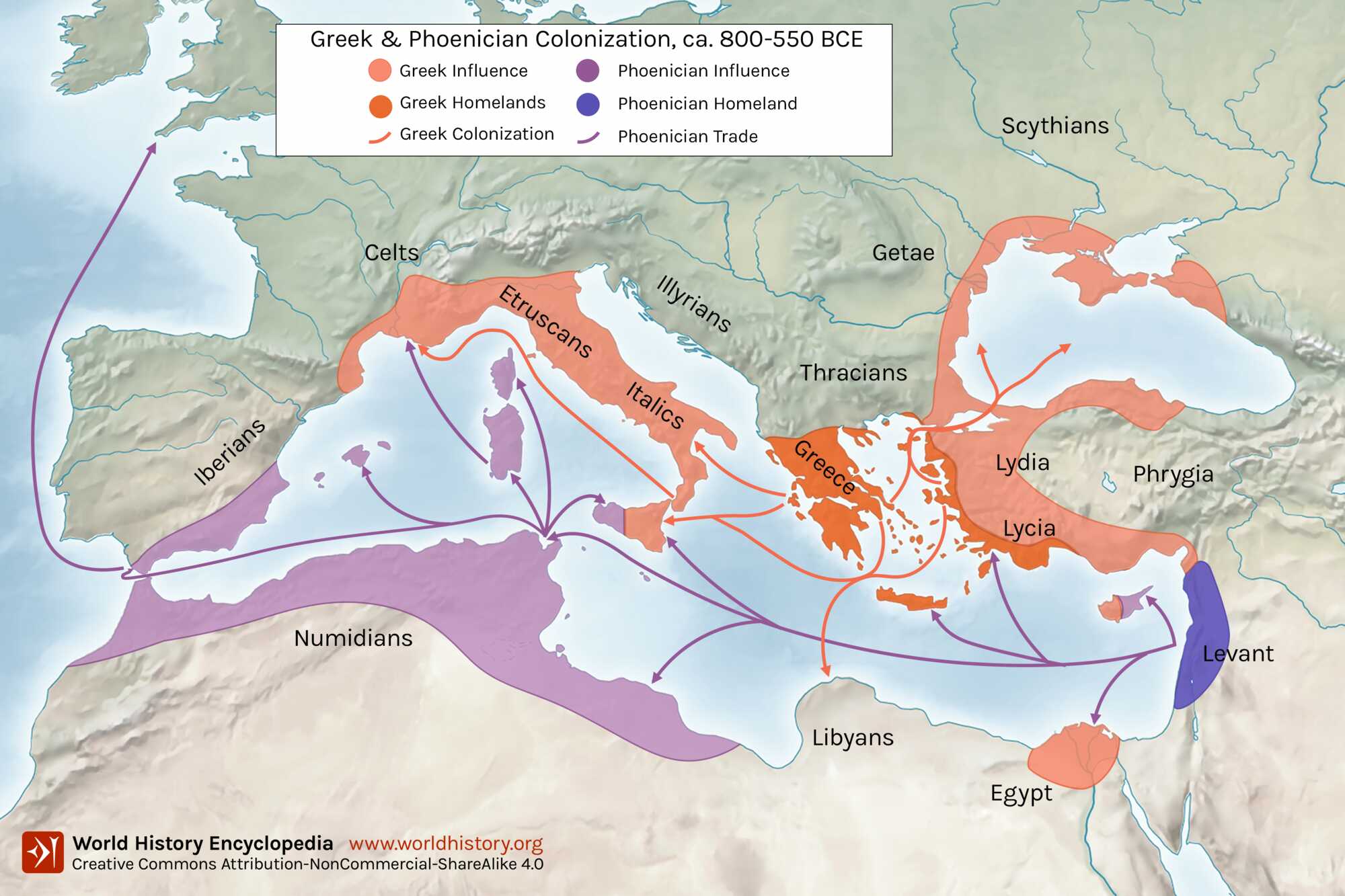

Greeks and their Early Colonies

Europe and the Mediterranean have long been important regions for innovation and power due to their favorable climate, resources, and ease of communication. Around 3000 BC, the first European civilizations emerged in the Aegean, starting in Crete and later expanding to mainland Greece during the Minoan-Mycenaean period.

This period saw complex trade networks stretching from Asia Minor to Sicily and southern Italy, with interactions between Mycenaean society and central European communities, although the exact influence remains debated. The collapse of the Mycenaean civilization around the 12th century BC led to significant cultural changes in central Europe, although it is unclear if these changes were directly caused by the Mycenaean collapse or other migrations and movements happening at the time.

However, it's likely that the breakdown of Mycenaean demand for resources, affected central European producers.

Mycenaean Lady from Knossos. Credits: Prof Saxx, CC BY-SA 3.0

A new core emerged with the rise of the Greek city-states around the 8th century BC, which dominated the Aegean and expanded their influence through colonization. As the Greek colonies expanded into the Black Sea, southern Italy, and Spain, peripheral regions were gradually incorporated into the core.

The relationship between core and periphery varied in scale, from Greek colonies being cores to their surrounding regions, to Rome's vast empire being divided into multiple interdependent peripheries. These relationships were dynamic and constantly evolving, shaped by economic exchanges and political systems.

This process continued through the Greco-Roman period until the collapse of the Roman Empire, which led to a fragmented Europe that eventually evolved into a dominant economic force by the 15th century, extending its influence to the Americas, Africa, and Asia. (Greeks, Romans and Barbarians: Spheres of Interaction, by Barry Cunliffe)

The Matter of Language

In the last two centuries BC, Roman culture underwent significant transformation due to contact with the Hellenistic East. This interaction had lasting impacts on Roman society, lifestyle, and even the Latin language, influencing the broader Mediterranean world. While the Roman process of "Romanization" is well-known, it was preceded by a form of "Hellenization," where Greek culture heavily influenced Roman life.

The paradox here is reflected in Horace's famous line, Graecia capta ferum cepit victorem ("Greece, conquered, took captive her savage conqueror"), suggesting that the Romans, though victorious, adopted much from Greek culture. However, this narrative oversimplifies the complexities of cultural change. While Rome did absorb much from Greece, it was far from being an uncivilized state prior to this contact.

Greek influence was present in Rome from its earliest days, as the historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus argued, calling Rome a "Greek city" from its inception.

Evander of Pallantium from Arcadia, the founder of the city which legend has, became Rome

Furthermore, the idea that Greek culture overtook Roman identity is too simplistic. For every instance of Roman adoption of Greek elements, there is evidence of Roman resistance and the retention of their distinct cultural practices. Instead of seeing this cultural shift as a one-way process, it might be better understood as a form of "bilingualism," where Romans could comfortably move between Greek and Roman languages and customs depending on the situation.

Valerius Maximus, in his Memorabilia, provides anecdotes about the Romans' emphasis on maintaining Latin as the official language, particularly in their dealings with the Greeks. This preference, he claims, was a demonstration of Roman authority, as they forced the Greeks to communicate through interpreters, thereby undermining their linguistic fluency and asserting the status of Latin internationally. Valerius argues that magistrates adhered to the principle of using Latin even in Greece, enhancing its prestige.

Valerius overlooks contradictory episodes where Romans did use Greek, such as when Cato the Elder spoke to the Athenians in Latin but had the speech translated into Greek. Valerius also neglects instances like the humiliation of L. Postumius Megellus, who, when attempting to negotiate in Greek, was ridiculed by the Tarentines for his poor command of the language. This incident highlights that not all Roman interactions were as dignified as Valerius suggests.

Gruen’s (an American classicist and ancient historian) analysis emphasizes the complexities in Rome’s use of language, noting that while some Romans preferred to impose Latin, others, such as generals like Scipio Africanus and Aemilius Paullus, were bilingual, leveraging their knowledge of Greek to consolidate power.

This use of Greek was sometimes a mark of superiority, complicating Valerius’ portrayal of Latin dominance.

The Generosity of Scipio Africanus, Public domain

Moreover, official Roman documents were often translated into Greek for effective communication, suggesting that practicality sometimes outweighed the desire to assert Latin's primacy. Ultimately, Valerius' chauvinistic reflection—that Romans, while learned in Greek, still believed in the superiority of their own culture and language—paints an incomplete picture. Gruen’s work provides a more nuanced understanding, showing that the Romans pragmatically balanced their use of both languages in maintaining control over their empire.

In the final moments of Suetonius' “Life of Augustus”, the aging emperor, as he nears death, is portrayed as being in an unusually celebratory mood. He chooses to spend his last days at the Bay of Naples, signaling a peaceful and reflective conclusion to his long and eventful reign:

“Every day he distributed to his companions a variety of small presents, including togas and pallia, setting the condition that the Romans should both dress and speak in Greek, and the Greeks in Roman clothes and language.”

Portraits and Images

Peter Wiseman (classical scholar and professor emeritus of the University of Exeter) uses the portrait of a Roman businessman from Delos to symbolize the process of Roman hellenization. This statue shows the man’s realistic Roman facial features, such as his jowls and protruding ears, juxtaposed with an idealized athletic Greek body. This contrast illustrates a key tension between Roman realism, which embraced imperfections, and the Greek preference for portraying individuals as heroic or divine figures.

Similarly, Paul Zanker (professor of Storia dell’Arte Antica at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa) discusses how the heroic nudity of Greek statues would have been unsettling to Romans in the Republican period. He highlights how Roman poets like Ennius criticized Greek customs such as nudity in the gymnasium, associating them with moral decline. Despite these concerns, Romans continued to adopt Greek traditions, including depicting emperors and even women in heroic nudity on coins.

The Roman adoption of Greek art and sculpture created a duality in their identity.

Herakles with the Apples of the Hesperides Roman 1st century CE from a temple at Byblos Lebanon. Credits: Mary Harrsch, CC BY-SA 4.0

In private settings like gardens, Romans embraced Greek culture, adorning their spaces with Greek mythological art, while in public, they were distinctly Roman, reflecting the contrast between the toga and pallium, or the switching between languages and behaviors.

This tension is also evident in art, such as the altar attributed to Domitius Ahenobarbus, which juxtaposes a Roman census scene with a Greek mythological wedding. This demonstrates how Romans consciously balanced both identities, reinforcing their Roman nature even when borrowing from Greek traditions.

This blending of cultural elements extended beyond mere artistic choices. Greek influences in private decoration were widespread in Roman villas, as seen in Pompeian wall paintings, where Greek mythology dominated the imagery.

However, this was not an expression of personal taste but a reflection of a collective Roman identity. Looking Greek in private, while maintaining Roman values in public, was part of the cultural uniform for Romans, allowing them to navigate between two worlds while preserving their distinctiveness.

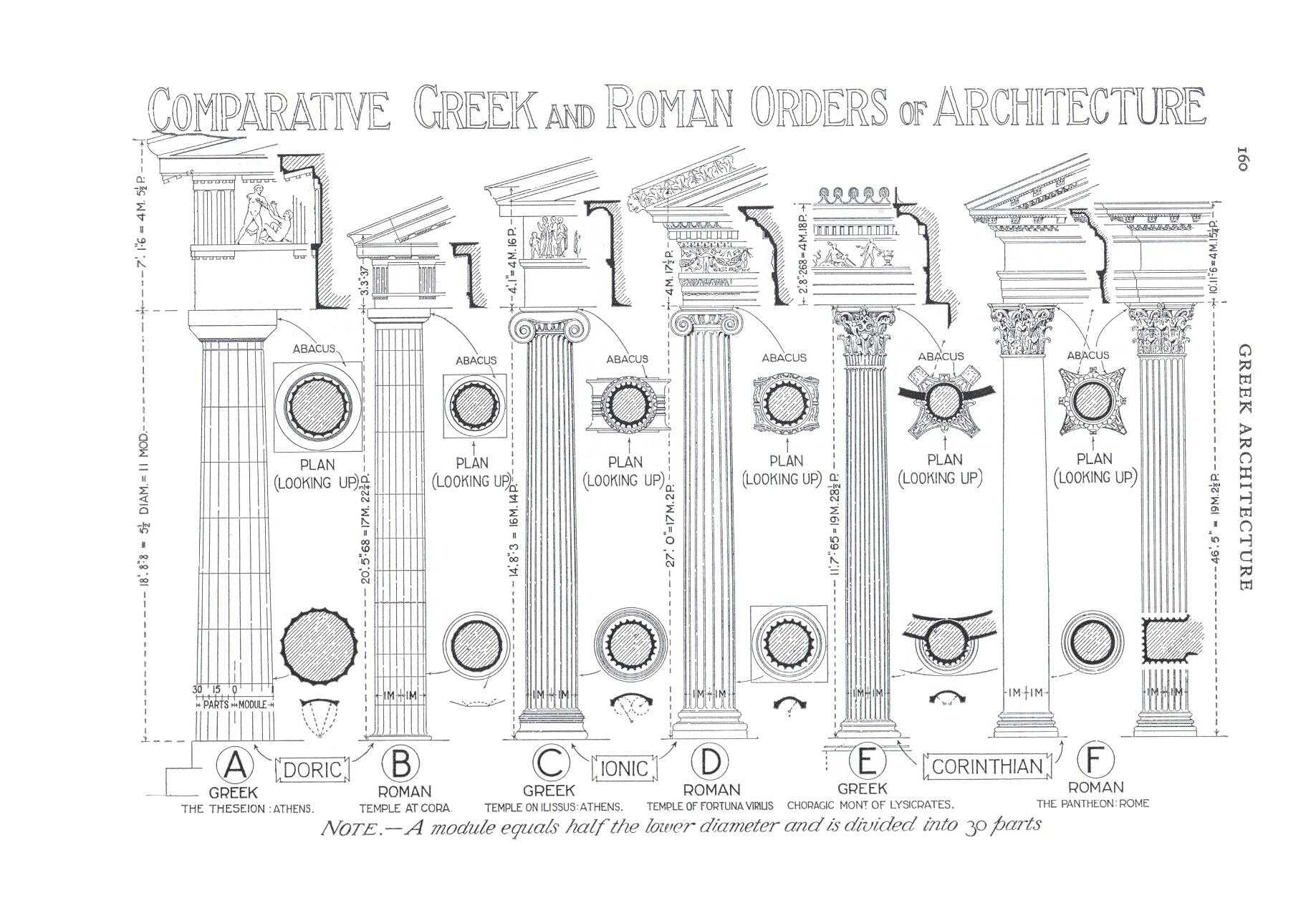

The Issue of Architecture

Vitruvius, in his De Architectura, highlights the contrasts between Greek and Roman (or Italic as he likes to put it) architecture, emphasizing how Roman architecture is distinct and tailored to the unique conditions of Roman life. He presents two parallel systems—Greek and Italic—contrasting features such as the Italic forum, a rectangular shape, with the square Greek agora, suggesting that the Roman form was influenced by the need for gladiatorial games.

Similarly, when discussing baths and theaters, Vitruvius showcases the differences between the Greek and Roman styles. Roman theaters, for example, are described as more rational and beautiful, with their design based on mathematical logic, involving four triangles, as opposed to the Greek model using three squares. Vitruvius does not merely replicate Greek theory; he adapts it, using it to support Roman architectural independence.

In domestic architecture, Vitruvius dedicates two books to contrast Roman houses, with their defining atrium, impluvium, and tablinum, against Greek houses, which he says are organized around different social imperatives, like the separation of men’s and women’s quarters.

Yet, despite this contrast, the Roman house contains many Greek elements—such as room names like triclinia and exedrae—showing the intermingling of cultures. Vitruvius even uses Greek architectural orders like Corinthian to describe aspects of Roman domestic spaces.

Ultimately, Vitruvius’ work suggests that Roman homes, while distinctively Roman in certain social functions, also allowed for Greek influences. The Roman house served as a space where both cultures coexisted, with different rooms reflecting either Greek or Roman traditions.

This complex intermixture of Greek and Roman elements allowed Romans to "go Greek" within the safety of their homes while maintaining a Roman public identity outside, reflecting the broader Greco-Roman cultural blending. (To be Roman, go Greek. Thoughts on Hellenization at Rome, by A.Wallace-Hadfull)

The Case of Cato Against the Greeks

Cato the Censor was one of the most ardent Roman critics of Greek culture, despite his extensive exposure to it. Born in 234 B.C. into a peasant family in Tusculum, Cato epitomized traditional Roman values: he was shrewd, tenacious, and conservative. He served with distinction in various roles, including military commander, provincial governor, senator, and consul, and was known for his strict moral stance as censor, where he sought to reform the political elite and uphold Roman virtues.

Cato was also involved in the earliest phases of Roman literature, supporting the poet Ennius and writing his own works. Despite his vocal opposition to Greek influence, Cato was deeply familiar with Greek culture through his travels, which took him to Greek cities in southern Italy, Sicily, and even Athens. In 191 B.C., he negotiated with the Athenians as a military tribune, speaking through an interpreter despite knowing Greek.

Although he knew prominent Greek figures like Themistocles and Pericles and was acquainted with Greek literature, including Homer and Isocrates (whom he mocked), Cato had little genuine interest in Greek culture and criticized Romans who he felt imitated the Greeks excessively. This contradiction between Cato's anti-Greek rhetoric and his knowledge of Greek culture remains a topic of debate among scholars.

Polybius recounts the story of A. Postumius Albinus, a Roman consul in 151 B.C., whose strong affection for Greek culture caused friction among the Roman political elite. Despite being well-versed in Greek from a young age, Albinus was mocked by Cato, particularly because Albinus chose to follow in the footsteps of Q. Fabius Pictor and L. Cincius Alimentus—both of whom had written Roman histories in Greek—and published his own Roman history in Greek, while apologizing in his preface for his lack of fluency.

Polybius criticizes Albinus for adopting what he describes as two major Greek flaws: a love of pleasure and an aversion to hard work. This sentiment mirrors Livy's later description of the Greeks as being more adept with words than with action.

Unlike Albinus, Cato harbored a deep disdain for Greek culture and was highly suspicious of anything associated with it. While Cato was not the only Roman who rejected Greek influence, his outspoken criticism was one of the few significant voices in opposition. Ultimately, the anti-Greek sentiment in Republican Rome faded without leaving much of a lasting impact, with Cato's protests being one of the few prominent expressions of it.

He writes to one of his sons:

"I will tell you in the appropriate place, my son Marcus, what I found out about those Greeks in Athens, and that it is a good thing to have a taste of their literature, but not to devour it.

I will drive home the point that their race is utterly vile and indocile. And believe you me, I speak as a prophet: once that race gives us its literature, it will corrupt everything, and it gets even worse if it sends us its doctors.

They have taken an oath amongst themselves to kill all barbarians with their medicine, but they do this only for a fee so that they may be trusted and may bring ruin the more easily.

They often refer to us, too, as barbarians and they defile us more foully than they do others by calling us "Opikoi." I have thus forbidden you dealings with their doctors."

Pliny the Elder recounts that Cato the Elder had a strong preference for traditional Roman remedies and taught these homespun cures to his son. Cato believed that these simple, Roman methods were key to his longevity. Pliny also mentions a specific incident where Cato accused the Peloponnesians of poisoning their wells, highlighting his mistrust of foreign practices, especially Greek ones.

This anecdote illustrates Cato's broader rejection of Greek influences, reinforcing his view that Roman customs, including medicine, were superior and sufficient for maintaining health.

Cultural comparisons often reflect the perspective of the writer or speaker. For example, Herodotus suggests that Greeks are cleverer than barbarians, and considers the Athenians the wisest among the Greeks. An ancient praise of Athens, attributed to a devotee of Isis, echoes this view, calling Athens the glory of Europe and Eleusis its shining sanctuary. Similarly, Julius Caesar contrasted Celtic customs to those of the Germans to highlight Celtic superiority.

Virgil uses the literary device of priamel—where a series of statements lead up to an emphasized final point—to deliver Anchises' prophecy. While acknowledging that Greeks excel in certain fields such as sculpture, rhetoric, and astronomy, Virgil ultimately elevates Rome’s unique capability to conquer and govern as a grander and more valuable skill. In this context, the earlier mention of Greek accomplishments serves as a prelude to Virgil’s main point about Roman supremacy in military and political matters. (Graecia Capta: Roman Views of Greek Culture, by Albert Henrichs)

Graecia Capta

Horace’s line, "Captured Greece captured its uncivilized conqueror and brought the Arts to rustic Latium," reflects the deep cultural exchange between Rome and Greece. While Greece was militarily conquered by Rome, its culture, arts, and intellectual traditions significantly influenced Roman life. This sentiment captures the paradox where Rome's domination over Greece led to its own cultural transformation, as it adopted and adapted many Greek cultural elements.

However, this interaction between Roman and Greek cultures was far from simple. As Horace's own context—learning a Latin version of The Odyssey as a boy in southern Italy—demonstrates, relations between Roman and Greek cultures involved a mix of dominance, submission, rivalry, and innovation. Latin authors did not merely imitate Greek culture but often engaged in a complex interplay of inheritance and transformation, reflecting Roman efforts to redefine their identity in relation to Greece.

Roman ecphrasis (the vivid description of works of art) serves as an example of this cultural competition. Roman writers used ecphrasis to demonstrate their receptivity to Greek culture while simultaneously competing with it, reshaping Greek influences to fit Roman ideals. This process of cultural exchange is also evident in visual culture, such as Pompeian wall paintings, where Greek mythological figures were depicted in a way that symbolized Roman conquest but also showed a fascination with Greek culture.

Thus, Roman ecphrasis and broader cultural practices reflect an ongoing negotiation of identity between Roman and Greek influences, with Romans constantly redefining themselves through a mix of cultural appropriation and resistance. This dynamic between Greece and Rome, was crucial in shaping Roman cultural identity, across time.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: