As I wrote in my very first book, a sort of postcard history of Fort Benton, around the turn of the 20th century a new means of communications sprung to life.

As a time-saving alternative to formal letters, a century ago postcards became essentially they were first in use one century ago. The Daily Missoulian in 1911 wrote: 'Picture postcards have been like a delightful vice that we first endured, pitied, then embraced. We were inclined to regard the first crude output of them as make-shifts for the lazy and picture cards for the children. Little by little they got in their insidious work — they were such blessed time-savers, they were such inexpensive souvenirs for the folks at home, they were such suggestive mementos of travel. And now we have found that there is no end to their uses, and we buy them by the cartload."

At the very same time as Charlie Russell was word-painting his way from working cowboy to international fame, another Texas and Montana working cowboy, Charles E. Morris, began recording on photographic plates what Charlie was portraying on canvas. Both presented a way of life that was vanishing with the end of the open range.

People are also reading…

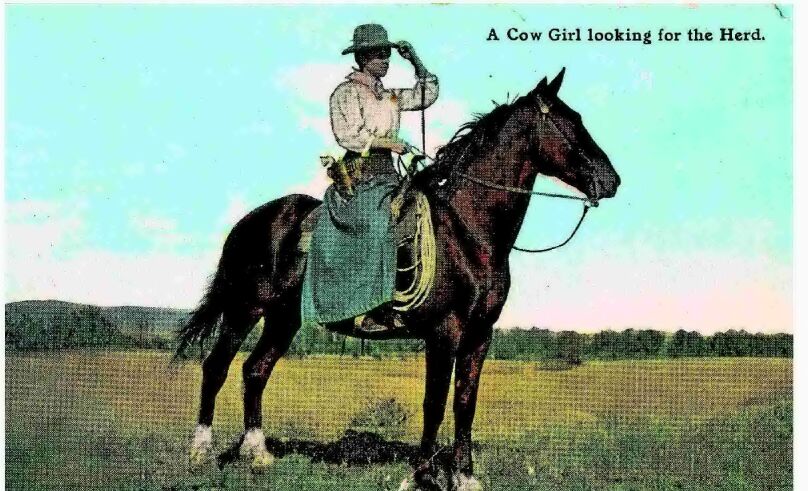

Charles Morris photographed working cowboys during the last great roundups of the open range, massive herds of cattle on a thousand hills, large flocks of sheep with their herders, Native Americans in their traditional adornments, and the last of the frontier military in the West.

In the fall of 1999, Morris's son, William A. "Bill" Morris, with able editing by his daughter Pamela, published "True, Free Spirit: a Biography of Charles E. Morris, Cowboy/ Photographer of the Old West." This was a labor of love and Bill's last hope to preserve the photographic works of his pioneering father. In Bill's words:

"Old-timers recall with fondness and pride the work of Chas. E. Morris, whose pictures both accurately and artistically portray the two decades which bridge the 19th and 20th centuries. My father knew as friends, early cattlemen, sheepmen, and Indians of this (northcentral) part of the state. He photographed their herds at roundups, their lands, and their families. In later years, friends spent many hours at his store reminiscing of their days on the range. Morris' photos graced the walls of their homes. Throughout the world they mailed Morris postcards of their West.

"In the past several decades, however, many people have enjoyed Chas. E. Morris photos without knowing the identity of the artist photographer. Numerous western books contain my father's photographs. Morris postcards have now become collectors' items.

"During 30 years of research on my father's photographs, I identified individuals, their homes, and their ranches; I found stories that led to anecdotes and nicknames, and, in the process, I gained a greater appreciation for the native West. Thus, my dream has been to fill in a true pictorial gap of an era, to memorialize the freely chosen work of a remarkable photographer and to honor the spirit of my father Charles E. Morris."

"Today it is difficult to appreciate the widespread use of postcards when

A tribute

In a glowing tribute to Charles E. Morris, Gene M. Gressley, founding director of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, put Charles Morris in the perspective of his time:

As the American West opened up, it produced in the nation at large an insatiable curiosity for this vast, beautiful, raw land. . . Charles Morris came onto this scene as a wrangler and photographer hobbyist. From the first, it was the intensive detail to recording the range life that fascinated Morris. He was devoted to recording the frustrations and weariness that he discovered in the countenances at dawn's break, or around the evening campfire. Sturdy, forthright, individualistic faces, sometimes passive, sometimes expressive — all were subject for his camera. But, above all, their images had integrity and enchanted the viewer, for Charlie Morris possessed perhaps the valuable trait for any photographer — patience.

... Many of Morris' views were harsh, direct, compelling — he left little room for ... romance visions. Morris was not interested in portraying the life of imagination. Rather, he maintained a hard, uncompromising examination when it came to selecting his next portrait be it of land or of man. . .

No one had to tell Charlie Morris to love the land but that emotion was tempered in Morris by his knowledge of how vicious, demanding and unyielding that land could be in a January blizzard or in a prairie fire in July — a land that could transform your soul, but at the same time sear that very soul by the extremes of its climatic ferocity. . .

If the viewer demonstrates the same patience as the photographer — the rewards will be significant. Morris' devotion to catching all facets of range life is embossed on every negative. The accouterments of his camp colleagues are there for all of us to see and appreciate. Artifacts such as the wide brimmed hats, so favored by Texans; a Meanes saddle, which many a cowboy oiled with loving care; mule eared boots, worn until the holes showed through the leather; spurs of all sizes, the design of which revealed much about the geography of the wearer; elaborate buckskin roping gloves perhaps the creation of a Northern Cheyenne; the mixture of long and short horn cattle of Texas or Oregon derivation mulling about in a distant range; and the quarter horse and his less frequent companion the Morgan at rest in a remuda — all parade before our eyes.

Charlie Morris has left us a pictorial legacy, as valuable as Granville Stuart did for our literary heritage.

Charlie helps his young friend

Charles M. Russell and Charles E. Morris worked the range in the same frontier country of northern Montana. Both rode the range, before capturing it: "Kid Russell" on canvas and in words; "Texas Kid" Morris with his scenes on glass plates and negatives.

As the time of the World's Fair in 1904 approached, Charlie Russell urged his friend Charles Morris to travel to St. Louis. This was sound advice, since at the great Lewis and Clark's Centennial Exhibition there, Morris entered the winning photograph "Cowboy on a Bucking Bronco" enhancing his role as an exceptional photographer of the open range. The cowboy in that scene was Roy Mathieson, on a bucking bronco; all four of the horse's legs were off the ground when Morris snapped the shot. This photo became Morris' iconic trademark.

Later, Morris photographed Charlie at his log cabin studio in Great Falls and marketed postcards of Russell's works including the "Waiting for a Chinook." Historian Harold McCracken declared that the postcards drawn by the "Cowboy" Artist and distributed by Morris, "no doubt did more than anything else" to fuel Russell's rise to fame as a great western artist.

Becoming a wrangler and photographer

Charles E. Morris was born in Glendale, Maryland, on June 29, 1876, just three days after the demise of Col. Custer and his 7th Cavalry in Montana Territory.

In 1890, Morris came West by way of Fort Worth, Texas, and in 1894 on to northern Montana's Milk River country, where the young "Texas Kid" became a range rider. Around 1900 he acquired a small camera, and during the winter of 1903, after riding for McNamara & Marlow, a large stock outfit, Morris went to LaCrosse, Wisconsin, where he took a course in photography. While there, he married Helen Schroeder and returned to Montana with his bride, settling in Chinook. From there, he began constant travel in a buckboard, visiting ranches to photograph families, babies, newlyweds, and dramatic western scenes, such as roundups, branding, roping.

Morris found a ready market when he sent his negatives to Germany where many were hand-tinted in color, then lithographed, and printed on the widely popular new means of communications, postcards. His western scenes found a ready market on the back of postcards, sold in stores throughout Montana and in the East.

In 1911, the Morris family left Chinook and moved to Great Falls. Morris continued to photograph the West including many scenes around his new home city until after World War I. Bank failures caused his studio to go broke, so Morris packed up his photographic equipment, glass plates and negatives, and stored them away in a metal trunk. For the next three decades, Morris operated, first, Charlie E. Morris Stationery Co., and then Morris Sporting Goods Co.

Charles E. Morris passed away May 16, 1938. Now more than a century after he photographed the last of the open range era, his legacy lives on through the color postcard scenes recording ranching, Native Americans, homesteading, and the frontier military. Today, those color ranch scenes on Morris postcards are widely popular with collectors —they buy them by the cartload.

His open range photographs are a fitting legacy for a Montana range rider and pioneer photographer.