China’s Reincarnation Monopoly Has a Mongolia Problem

The twin lines of the Dalai Lama and the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu have shaped geopolitics for centuries.

At a public teaching in Dharamsala, India, on March 8 this year, the Dalai Lama mentioned, almost in passing, the presence of the boy reincarnation of the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu—a Mongolian high lama like the Dalai Lama himself. Mongolia and Tibet share a Buddhist tradition, usually known as “Tibetan Buddhism,” in which lineages of reincarnated lamas play an important role. The Jebtsundamba Khutughtu line has traditionally led Buddhists in Mongolia, just as the Dalai and Panchen Lamas have in Tibet.

Bizarrely, for an atheist communist party-state, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims that only it can decide on reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhist lamas—a privilege the PRC says it inherited from the Manchu rulers of the Qing Empire, which included both Mongolia and Tibet. But the PRC controls only a portion of historical Mongolia, a Chinese region known as Inner Mongolia, while Mongolia itself, once protected from Chinese ambitions by its status as a Soviet satellite, is now an independent country. The history of the Dalai Lama and the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, and the decisions their predecessors made, have shaped the map of Tibet, China, and Mongolia today.

At a public teaching in Dharamsala, India, on March 8 this year, the Dalai Lama mentioned, almost in passing, the presence of the boy reincarnation of the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu—a Mongolian high lama like the Dalai Lama himself. Mongolia and Tibet share a Buddhist tradition, usually known as “Tibetan Buddhism,” in which lineages of reincarnated lamas play an important role. The Jebtsundamba Khutughtu line has traditionally led Buddhists in Mongolia, just as the Dalai and Panchen Lamas have in Tibet.

Bizarrely, for an atheist communist party-state, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims that only it can decide on reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhist lamas—a privilege the PRC says it inherited from the Manchu rulers of the Qing Empire, which included both Mongolia and Tibet. But the PRC controls only a portion of historical Mongolia, a Chinese region known as Inner Mongolia, while Mongolia itself, once protected from Chinese ambitions by its status as a Soviet satellite, is now an independent country. The history of the Dalai Lama and the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, and the decisions their predecessors made, have shaped the map of Tibet, China, and Mongolia today.

On a visit to Mongolia in 2016, the Dalai Lama announced that this 10th reincarnation had been born. (His predecessor had died in 2012.) The People’s Republic of China then sanctioned Mongolia over the Dalai Lama’s visit. In 2007, the PRC State Administration for Religious Affairs had issued “Order Number Five,” a decree that “living Buddhas” in Tibetan Buddhism can only be reincarnated within the PRC in accordance with officially stipulated procedures, and “shall not be interfered with or be under the dominion of any foreign organization or individual.” But the new Jebtsundamba was neither born, recognized, nor bureaucratically approved in China.

In fact, news accounts note that the Mongolian boy recognized as the 10th Jebtsundamba was born in the United States. Some suggest he could play a role in identifying the reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama, though the current Dalai Lama has said that he may not reincarnate at all. But the March meeting of the Dalai Lama and the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu before an audience of a few hundred monks, nuns, and Mongolian visitors, is more significant than these news items have portrayed. That’s because the 87-year-old Dalai Lama and 8-year-old Jebtsundamba Khutughtu already have a history together—one that started in the 17th century.

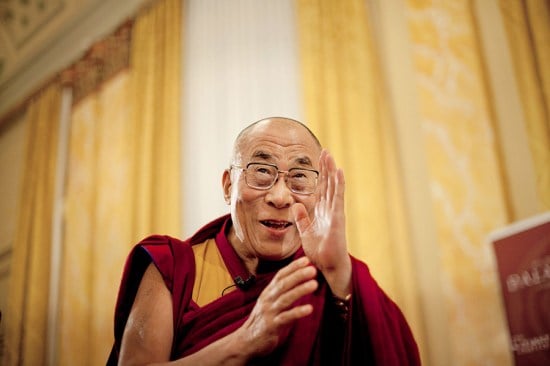

- The Dalai Lama points to the audience at a Buddhist school as part of his three-day visit to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, on Nov. 5, 2002. Ng Han Guan/AP

- Mongolian Buddhists wait in line outside a Buddhist school during the Dalai Lama’s visit to Ulaanbaatar on Nov. 5, 2002.Ng Han Guan/AP

Tibetan Buddhism seems mysterious, and “Jebtsundamba Khutughtu” is admittedly a mouthful. But they’re both important. Among other things, they help explain why the PRC today includes Xinjiang, Tibet, and some traditional Mongol lands—and why it has trouble reconciling these territorial possessions with its increasingly narrow nationalism and policies to assimilate non-Han peoples.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claims authority over Tibetan Buddhism. In 2018, to tighten its grip, the CCP transferred the State Administration for Religious Affairs, formerly a government bureau, into the United Front Work Department, thus putting the party directly in charge of religion.

The PRC controls Tibet, but Tibetan Buddhism is no more exclusively Tibetan than Roman Catholicism is Roman. Both are world religions with followers around the globe. Reincarnating lamas, or more precisely, Buddhist masters who can control their own reembodiment, such as the Dalai Lama and Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, are known as tulku in Tibetan and somewhat inaccurately as huofo (living Buddha) in Chinese. Tulku lineages have been identified in Europe and North America as well as in Tibetan cultural regions in Mongolia, China, India, and other parts of Asia. Beijing has not yet commented on the recent appearance of the current Jebtsundamba, but for CCP authorities to attempt to manage the recognition of a Mongolian tulku would be akin to Beijing wanting a say in the Vatican’s selection of cardinals in Mexico or Nigeria.

Tibetan Buddhism, especially the Gelugpa school led by the Dalai Lama, has been intertwined with the Mongols from the beginning. In the aftermath of the Mongol Empire, the Gelugpa rose in parallel with other imperial contenders across the Eurasian continent, including Mongol tribes, the Manchus who established the Qing Empire, and even Muscovite Russia.

These rivals drew on two main sources of legitimacy. First, every ruler wanted to be a “khan,” but to do so convincingly required Chinggisid lineage—that is, descent from Genghis Khan. Second, patronage of, and backing from, transnational religions was key. In western parts of the former Mongol Empire, Islam served this function. In the east, it was Tibetan Buddhism, and khans studied with lamas and got themselves and their children recognized as tulkus or other important reincarnations.

It was a Chinggisid Mongol khan in the 16th century who first coined the title “Dalai Lama,” combining the Tibetan word for priest with a Mongolian word meaning “oceanic wisdom,” and bestowed it on a lama in the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Gelugpa school, one of four major traditions in Tibet, expanded its temporal and religious power in Tibet and beyond through strategic alliances with Mongol leaders and other powers, including the young Qing state, ruled by Manchus who had conquered north China in 1644 but weren’t done yet.

Buddhist monks await the arrival of the Dalai Lama at Gandantegchinlen Monastery in Ulaanbaatar on Aug. 26, 2006.PETER PARKS/AFP/Getty Images

The Fifth Dalai Lama (in office 1642-1682) and his officials were adept at this high-stakes diplomatic game: The Fifth visited Beijing as a youth in the early 1650s, and there declared the Qing emperor to be an incarnation of a bodhisattva named Manjushri. But the Gelugpa kept their options open, and two decades later cemented relations with the Qing’s nemesis to the northwest, the Junghar Mongols, by granting the title “Khan by Divine Grace” to Galdan, a Junghar prince who had studied in Tibet.

For Galdan to be a khan departed from tradition, since he was not a Chinggisid—but by then, the Gelugpa school enjoyed so much clout that the Dalai Lamas could play khan-maker. More than that, on the Dalai Lama’s invitation, Galdan’s Junghars seized southern Xinjiang, with its oasis farms and silk routes to Central Asia. In their own labor transfer scheme, the Junghars moved Uyghurs from southern Xinjiang north to farm the Ili Valley and help build their capital in Jungharia, now northern Xinjiang.

By this time, then-Qing Emperor Kangxi had only just emerged from the shadow of his own regents; after a prolonged struggle with Han generals left over from the Ming Empire, he’d conquered southern China and annexed Taiwan; he’d also driven the Russians out of the Manchu homeland and signed a mutually advantageous treaty with them.

But the Junghars posed the greatest challenge of all, threatening to forge a Tibetan Buddhist-Mongol axis from Tibet through Xinjiang to Mongolia, commanding the loyalty of powerful nomads across the entire western and northern frontier of the Qing. The Junghars had convened a pan-Mongol Buddhist congress, attended by representatives from Tibet, Qinghai, Mongolia, and even as far as the Volga River. And now Galdan’s forces were riding eastward to threaten the Khalkha Mongols—the main people in the territory that is modern-day Mongolia. Kangxi was worried. But at this moment, the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu made a decision that would shape the map of the modern world.

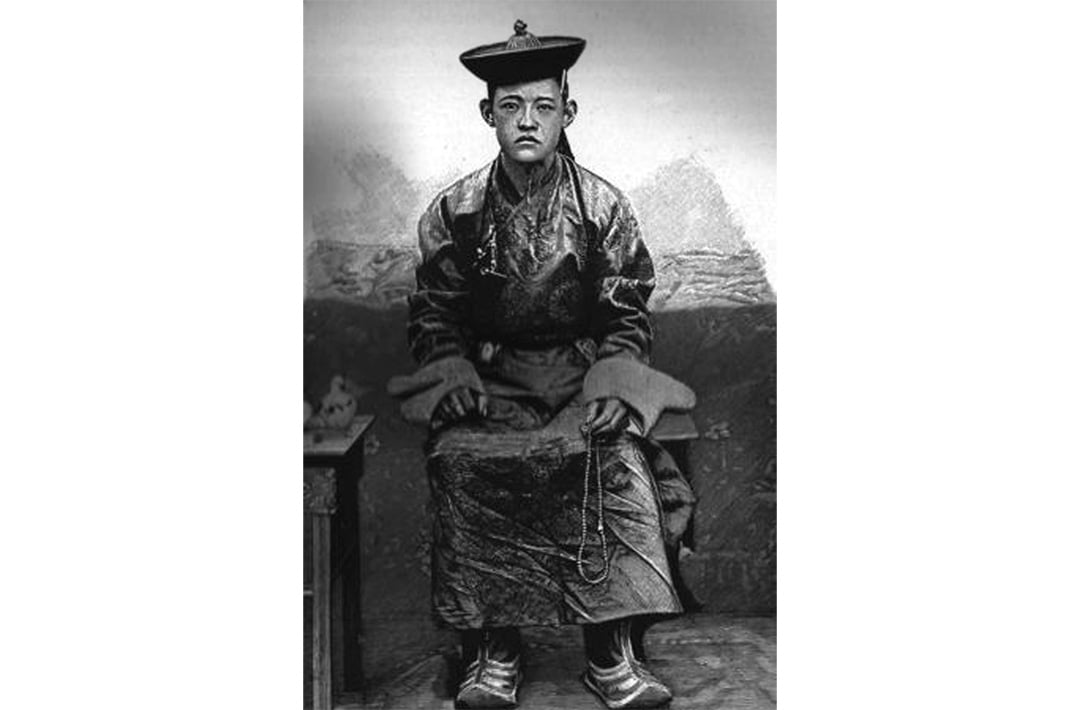

The Bogd Khan poses for a photo as a young boy in the late 1800s.History/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

The first Jebtsundamba was himself the son of a Chinggisid khan, a Khalkha whose pastures spanned outer Mongolia. As the principal Gelugpa lama among the Khalkha Mongols, it fell to the Jebtsundamba to decide what the Khalkhas should do in the face of Junghar pressure. Which way should they jump? Should they seek aid with the Russians? Or submit to the Qing?

The Jebtsundamba chose the Qing, because they were patrons of the Gelugpa church. He led tens of thousands of Khalkhas south, where in a ceremony at Dolon Nor in 1691, they became Qing subjects. Several far-reaching developments flowed from this decision: Since there were no longer any independent Chinggisid descendants of the former Mongol emperors of China, the Qing were able to convincingly assume the Chinggisid mantle, enhancing their credibility among Mongols everywhere. With the help of the new infusion of Khalkha cavalry power, Kangxi and subsequent Qing emperors not only defeated Galdan, but over subsequent decades smashed the Junghar confederation, conquered outer Mongolia, Jungharia, and southern Xinjiang, and replaced the Junghars as the Gelugpa’s military patrons, thus establishing a Qing protectorate over Tibet.

The Qing managed its new empire in Inner Asia with remarkable success for a century, in large part because it enjoyed Chinggisid and Tibetan Buddhist legitimacy, and did not interfere with, let alone attempt to Sinicize, the culture of its Mongol, Tibetan, or Muslim subjects in Inner Asia. To the contrary, the Qing endeavored to keep Han Chinese out of Inner Asia, or at least limit their settlement, even rooting up illegal Han settlers in Mongolia until the mid-19th century.

Mongolian monks reach for candies from a child after the Dalai Lama gave a lecture in Ulaanbaatar on Nov. 6, 2002.Ng Han Guan/AP

But as the Qing wobbled in its last decades, weakened by the Taiping Rebellion and exactions from Western imperialists, the court took the advice of Han scholar-officials and began promoting Chinese settler colonization of Manchuria, Mongolia, and Xinjiang to extract resources and stave off Russian encroachment. Tibet was too far and too high for Chinese settlers, but the Qing dispatched an army to put Tibet under direct rule in 1910—on the eve of its own demise—forcing the then-Dalai Lama, the predecessor of today’s incarnation, to flee to India.

Under these circumstances, the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, at that time the eighth incarnation, was charged with another momentous decision. Concerned about Chinese colonization, when the Qing crumbled in late 1911, the Jebtsundamba along with Khalkha princes declared Mongolia’s independence from the Qing—just as revolutionaries in China declared China independent. As soon as the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in early 1913, he followed suit. The eighth Jebtsundamba, under the title Bogd Khan (Sacred Khan), became head of state in Mongolia, and the 13th Dalai Lama the head of state in Tibet.

Tibetan Buddhist monks walk to unveil a thangka painting at the Gartse Monastery in Guashize, China, on Feb, 28, 2018.JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/Getty Images

The diplomatic history thereafter is messy, since Britain, Russia, and the Chinese republics all, for their own self-interested reasons, contested Tibetan and Mongolian independence. Khalkha Mongolia would remain independent of China, but Mongol Tibetan Buddhists suffered under Soviet control. Still, at that moment in 1912, three states emerged clearly from the rubble of the Qing: an unstable Republic of China that militarists and revolutionaries vied to control; and Mongolia and Tibet, each under Tibetan Buddhist lamas as heads of state.

It was another Qing emperor, Qianlong, who introduced the golden urn system through which today’s CCP hopes to manage the discovery of high Tibetan Buddhist lamas. Impatient with the nepotistic pipeline funneling Mongol nobility into the tulku ranks, in the late 18th century, Qianlong required that tulku candidates be chosen in a supervised ceremony by drawing the name a from a golden urn. This did enhance Qing control of Tibetan Buddhism to some degree, but as Max Oidtmann has shown in a recent book, to the extent that the golden urn was used, it was accepted because Tibetan Buddhists, too, understood the dangers of corruption and embraced an effort by a Qing khan, himself a devout Buddhist and embodiment of the bodhisattva Manjushri, to depoliticize the process of tulku selection.

By putting the CCP’s Organization Department in charge of religious matters, Chinese President Xi Jinping has done the opposite: He has further politicized the selection of tulkus. Mongolia is a small democracy, sandwiched between increasingly authoritarian China and Russia, and economically dependent on maintaining good trilateral relations. But Mongolia’s independent political status challenges the CCP historical narrative that everything once part of the Qing Empire is now part of the PRC—the very argument underpinning Beijing’s assertions about Taiwan.

The Dalai Lama waves during a news conference in a Copenhagen hotel on May 30, 2009.SCANPIX DENMARK/AFP/Getty Images

By the same neocolonialist historical logic by which it claims Taiwan, Beijing should also claim Mongolia, as the Republic of China under the Kuomintang did before the 1990s. But because Mongolia became independent thanks to intervention by the fellow-communist Soviet Union, the CCP broke with Republic of China precedent and recognized Mongolia in 1949. How Beijing reacts to the new Jebtsundamba—a high lama in a religion it claims to control—thus implicates Beijing’s theory of the case regarding Taiwan, as well. If Beijing says there can be no Mongolian high lama without its say-so, that reveals the ludicrous overreach of its policy toward Tibetan Buddhism. But if it says nothing while a Qing-era lineage of tulku-leaders continues autonomously in Mongolia, that reminds us that the PRC is not the full-blown reincarnation of the Qing that it says it is.

The first Jebtsundamba led his people into the Qing Empire, and the eighth led them away from China. In so doing, each assessed which path he thought best served the faith. This is a heavy legacy to lay on the shoulders of an 8-year-old boy, and it is reasonable to question a religious institution that channels small children into a life of celibate study and political pressure. Still, the CCP’s Order Number Five doesn’t lessen that burden, nor is it likely to bring the khans and lamas together again.

James A. Millward is Professor of History in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

More from Foreign Policy

-

Fire and black smoke surround a man carrying a large tire in the street. 10 Conflicts to Watch in 2025

As Trump returns to office, the question is whether change will come at the negotiating table or on the battlefield.

-

Donald Trump holds a baseball bat while participating in a Made in America event with companies from 50 states featuring their products in the Blue Room of the White House July 17, 2017 in Washington. Trump Can’t Bully the Entire World

Loudly making threats doesn’t amount to a foreign policy.

-

A grid of 29 foreign-policy books part of the anticipated releases in 2025. The Most Anticipated Books of 2025

The biggest releases in foreign affairs, history, and economics.

-

A man holds his fist in the air and shouts along with a crowd of other men holding placards. 8 Simmering Threats You Shouldn’t Ignore in 2025

From Moldova to Mexico, these conflicts are currently flying under the radar but could emerge as major flash points.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.