Abstract

The recently discovered 125 GeV boson appears very similar to a Standard Model (SM) Higgs, but with data favoring an enhanced h → γγ rate. A number of groups have found that fits would allow (or, less so after the latest updates, prefer) that the  coupling have the opposite sign. This can be given meaning in the context of an electroweak chiral Lagrangian, but it might also be interpreted to mean that a new colored and charged particle runs in loops and reinforces the W-loop contribution to hFF, while also producing the opposite-sign hGG amplitude to that generated by integrating out the top. Due to a correlation in sign of the new physics amplitudes, when the SM hFF coupling is enhanced the hGG coupling is decreased. Thus, in order to not suppress the rate of h → WW and h → ZZ, which appear to be approximately SM-like, one would need the loop to 'overshoot', not only canceling the top contribution but producing an opposite-sign hGG vertex of about the same magnitude as that in the SM. We argue that most such explanations have severe problems with fine-tuning and, more importantly, vacuum stability. In particular, the case of stop loops producing an opposite-sign hGG vertex of the same size as the SM one is ruled out by a combination of vacuum decay bounds and Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) constraints. We also show that scenarios with a sign flip from loops of color octet charged scalars or new fermionic states are highly constrained.

coupling have the opposite sign. This can be given meaning in the context of an electroweak chiral Lagrangian, but it might also be interpreted to mean that a new colored and charged particle runs in loops and reinforces the W-loop contribution to hFF, while also producing the opposite-sign hGG amplitude to that generated by integrating out the top. Due to a correlation in sign of the new physics amplitudes, when the SM hFF coupling is enhanced the hGG coupling is decreased. Thus, in order to not suppress the rate of h → WW and h → ZZ, which appear to be approximately SM-like, one would need the loop to 'overshoot', not only canceling the top contribution but producing an opposite-sign hGG vertex of about the same magnitude as that in the SM. We argue that most such explanations have severe problems with fine-tuning and, more importantly, vacuum stability. In particular, the case of stop loops producing an opposite-sign hGG vertex of the same size as the SM one is ruled out by a combination of vacuum decay bounds and Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) constraints. We also show that scenarios with a sign flip from loops of color octet charged scalars or new fermionic states are highly constrained.

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The Higgs discovery represents a major milestone in particle physics [1, 2]. It brings renewed urgency to the question of naturalness: if the Higgs has precisely the properties predicted by the Standard Model (SM), we may be forced to confront the possibility that we live in what is, to all appearances, a finely-tuned world. The experimental results so far present us with tantalizing hints that σ × Br(h → γγ) may be substantially larger than the SM prediction [3, 4]. Indeed, a number of groups of theorists have attempted to fit the data allowing for non-SM Higgs couplings, both before [5–15] and after [16–24] the 4 July 2012 discovery announcement.

Although many details of the fits and the allowed parameter space are explained in these references, we can summarize the situation (keeping in mind that the error bars are still rather large) by saying that the Higgs σ × Br to WW and ZZ is essentially consistent with the SM, the rate to γγ is somewhat high, and the rate to τ leptons may be low although Tevatron results suggest that the b-quark rate is not very suppressed. In almost every way, the Higgs appears to be nearly SM-like. Nonetheless, fits of the Higgs couplings allow (or even, less so after recent ATLAS h → WW results, favor) a region with Rt = −1, i.e. a flipped sign of the Higgs–top–top coupling1. This sign is fixed in the SM without higher-dimension operators, but can be altered in the electroweak chiral Lagrangian. In other words, we can always choose the phase of the top mass so that mt is a positive real number, but then the relative sign of the coupling  may be changed by new physics. Another interpretation, however, could be that new particles run in the loop for both h → gg and h → γγ and contribute amplitudes with the opposite sign of the top.

may be changed by new physics. Another interpretation, however, could be that new particles run in the loop for both h → gg and h → γγ and contribute amplitudes with the opposite sign of the top.

To illustrate the possibility of achieving a better fit to the data with new colored and charged particles, we have performed a simple fit to the CMS and ATLAS combined 7 and 8 TeV data in the γγ [3, 4], ZZ [25, 26], and WW [27, 28] channels, shown in figure 1. We use Δχ22d.o.f. = 2.30,6.18, and 11.83 to define the 1σ, 2σ, and 3σ contours. Because our goal is to illustrate a qualitative point more than to extract precision information from the data, we omit other decay modes as well as vector boson fusion and other production channels. Furthermore, we do not take all signal strength values at the same mass, for instance taking the ATLAS γγ channel σ × Br to be 1.9 ± 0.5 times the SM rate despite the fact that this value is attained for a signal hypothesis of mh = 126.5 GeV whereas other channels we take into account have mh = 125 GeV. Nonetheless, this simple fit gives a similar result to the many other recent analyses, with the best-fit point having a slightly smaller hGG coupling Γ(h → gg) = 0.9 ΓSM(h → gg) and a substantially larger hγγ coupling Γ(h → γγ) = 1.9 ΓSM(h → γγ). Note that the recent ATLAS WW result [28], with an observed rate (combining 7 and 8 TeV data) of 1.4 ± 0.5 times the SM expectation, partially counteracts the tendency of previous h → WW searches to prefer a diminished gluon fusion rate.

Figure 1. Fit of the WW, ZZ and γγ channels in the ATLAS and CMS 7 + 8 TeV data, allowing the hGG and hFF amplitudes to vary. The best-fit point is marked with the orange star, which is surrounded by 1, 2, and 3σ orange contours. The SM value (1,1) falls on the 1σ contour. The green dot-dashed curve illustrates the possible contributions from top partners, with the best-fit point along this curve marked with the open green square. This uses the relationship between the effect of stops on photons and gluons explained below in equations (4) and (5). The left- and right-hand plots show the same information, at left in the plane of gg and γγ partial widths and at right in the plane of coefficients a and c for Higgs couplings to vectors and fermions, respectively. (The green line for stops, strictly speaking, does not correspond to a deviation in the (a,c) coefficients, but its effect on production rates and branching ratios is equivalent to varying c, as shown.) This fit is for illustrative purposes only; the reader can find fits incorporating more channels and more thorough statistical treatments in the literature.

Download figure:

Standard imageFigure 1 also shows a curve of values that can be obtained with stops running in loops. Beginning from the SM point (1,1) and moving to the left, one sees that initially increasing the h → γγ rate decreases the h → gg rate, but at a certain point the curve turns around and both rates increase. This corresponds to reversing the sign of the hGG amplitude. The best-fit point on the curve has Γ(h → gg) = 0.8ΓSM(h → gg) (but with an amplitude of opposite sign) and Γ(h → γγ) = 2.3ΓSM(h → γγ). A similar observation appeared recently in [18]. However, it is important to realize that this is a very large loop effect, inverting the sign of the hGG amplitude from a top loop by subtracting a new contribution twice as large. Such large loop effects are not expected in the 'natural SUSY' scenario that often motivates consideration of light stops [29, 30], and are not innocuous. In particular, the same particles that run in these loops affect the Higgs potential, and if they are scalars, they have a potential of their own with possible new minima. We will argue that these effects are not benign, and trying to use the upper branch of the green curve in figure 1 to explain the data brings with it a host of new problems, whether the new particles are scalars or fermions.

2. Loop effects of charged and colored particles

2.1. Computing the effects

New particles that obtain a portion of their mass from the Higgs boson also alter the Higgs potential. We will be primarily concerned with their effect on the Higgs quartic, which determines the mass of the Higgs boson once the appropriate vacuum is found. To compute the shift in the quartic, we use the one-loop Coleman–Weinberg potential determined from a mass matrix  for new bosons and fermions,

for new bosons and fermions,

expressing the mass of the new particles in terms of the Higgs field H, expanding as a function of H, and reading off the coefficient of |H|4 to obtain a correction δλ to the quartic. Note that when expanding around the origin and reading off the |H|4 term, we neglect possible |H|4 log|H|2 terms that would arise from fields that are massless when the Higgs has no vacuum expectation value (VEV). Because we are interested in negative contributions to the hGG coupling, the dominant effect of increasing the Higgs VEV should be to decrease the mass of the fields we integrate out, and this is a reasonable approximation to use. (Note that in equation (1), μ, as is customary, denotes a renormalization scale.)

Corrections to the effective Higgs couplings to photons and gluons are easily understood in terms of the low-energy theorem [31, 32]. Namely, to read off the effective coupling induced by integrating out heavy particles, one treats them as a Higgs-dependent mass threshold in the beta function, obtaining the effective vertex from the running of 1/g2, as a function of the Higgs-dependent mass matrix M2(h) for the new states:

with Δb the beta function coefficient of the states that were integrated out2. An analogous statement holds for couplings to photons, the only difference being that it is the electromagnetic beta function coefficient that appears. In the case that the mass of the new particles is not much greater than half the Higgs mass, it can be important to take into account mass-dependent corrections to the low-energy theorem. In particular, for fermions these corrections are  and for scalars

and for scalars  .

.

If we have a new colored state that carries charge Q and is in an SU(3)c representation with quadratic Casimir C2(R), we can evaluate its effect by rescaling the contribution of the top loop amplitude in the SM. Namely, defining

we find that they are related by

where the sign of the square root is determined by the sign of the hGG amplitude, and

As discussed recently in, for instance, [34], the choices of charge and representation are fairly restricted by needing particles that can decay to the SM. This expectation is based on the lack of detected stable particles of exotic charge in searches of anomalously heavy isotopes of light elements [35, 36]; perhaps ambitious readers may consider exotic cosmologies that avoid such constraints, but we will proceed under the assumption that new exactly stable colored and charged particles do not exist. We plot the possible effects of several examples of plausible charge assignments in figure 2. Each of the curves has two branches meeting at Rg = 0, with the upper branch corresponding to the case with an inverted sign for the hGG amplitude. Notice that charge-2/3 color triplets can improve the fit, but other charges for color triplets are of little help in the inverted sign regime. (The charge 5/3 triplet discussed in [34] may help the fit slightly, but the best fit points have a negative sign of the new contribution to the hGG amplitude which is too small to completely cancel the SM amplitude, and hence the overall Higgs production rate decreased. This predicts that the measured rate for h → WW,ZZ should decrease in the future.) The combination of a neutral and charge 1 color octet with the same mass can give an interesting improvement in the fit. A color sextet of charge 2/3 can also offer some improvement. Other recent work in which new colored particles contribute to Higgs production and decay can be found in [37–40]. (As this paper was nearing completion, Dorsner et al [41] appeared advocating color octet or sextet scalars with opposite-sign hGG amplitude as a hint of unification. Given the vacuum stability and tuning arguments discussed below, we are much less sanguine.)

Figure 2. Fit of the WW, ZZ and γγ channels in the ATLAS and CMS 7 + 8 TeV data, with 1σ and 2σ contours as in the left-hand plot of figure 1, but now showing the values achieved by adding particles in the loop in a variety of representations of SU(3)c and U(1)EM. The curves are determined using the relationship between the effect of new particles on photons and gluons explained in equations (4) and (5). The case '0 + 1' for the charge indicates that we take the net effect of a colored but uncharged particle and an equal-mass colored particle with charge 1, as in the case of Manohar–Wise scalars.

Download figure:

Standard image2.2. New fermionic states

Let us first consider the case of new fermionic states. We assume two vectorlike pairs of fermions,  and

and  with charges such that Yukawa couplings

with charges such that Yukawa couplings  and

and  are allowed (e.g. ψ a doublet, χ a singlet with appropriate hypercharges), so that the mass matrix in the basis

are allowed (e.g. ψ a doublet, χ a singlet with appropriate hypercharges), so that the mass matrix in the basis  is

is

In this case, the correction to the h → gg amplitude, relative to the SM amplitude from a top loop (and neglecting mass effects) is

In particular, because there are vectorlike masses that are split by the mixing terms proportional to the Yukawas, we get a negative contribution to the amplitude. The factor  is the ratio of the SU(3)c beta-function coefficient of the representation that ψ and χ transform under, relative to the beta-function coefficient of a triplet.

is the ratio of the SU(3)c beta-function coefficient of the representation that ψ and χ transform under, relative to the beta-function coefficient of a triplet.

Loops of fermions contribute a correction to the Higgs quartic, which in the special case mψ = mχ = m is

As explained below equation (1), this was calculated by inserting the mass matrix of the fermions into the general formula and reading off the coefficient of |H|4 (i.e. expanding around the origin of the potential). The result in the more general case mχ ≠ mψ is listed in the appendix. Notice that the logarithmic term here can be interpreted as encoding a beta function coefficient. Because the full renormalized potential must be independent of μ, the tree-level quartic must run in such a way as to cancel the μ-dependence of the Coleman–Weinberg potential. In other words, if we work in renormalized perturbation theory and impose renormalization conditions to relate our Lagrangian parameters to physical observables, all dependence on unphysical scales must cancel. The reader to whom this argument is unfamiliar may find the very clear discussion in chapter IV.3 of the textbook [42] enlightening.

2.3. New scalar states

Assume a mass matrix

This arises, for instance, from a singlet scalar ϕ1 and a doublet scalar ϕ2 which each have mass terms, |H|2|ϕi|2 quartic couplings with the Higgs, and a trilinear ϕ1ϕ2H coupling. It is the form that holds for squarks in the MSSM. The correction to the h → gg amplitude relative to the SM amplitude is

The factor of 1/4 arises from the relative beta function coefficients of a single color-triplet scalar and the top quark, whereas the factor  again corrects for the case when the field is not in the 3 of SU(3)c. As in the case of fermions, the effect of mixing (here proportional to A) is to split the mass eigenstates and thus give a negative contribution. On the other hand, the quartic couplings λ1,2 can give contributions of either sign.

again corrects for the case when the field is not in the 3 of SU(3)c. As in the case of fermions, the effect of mixing (here proportional to A) is to split the mass eigenstates and thus give a negative contribution. On the other hand, the quartic couplings λ1,2 can give contributions of either sign.

The correction to the Higgs quartic in the case where the mass parameters m1 and m2 are equal is

The result in the more general case m1 ≠ m2 is given in the appendix. To compare to a more familiar expression: if the scalar states are stops in a supersymmetric theory, we have m21 = m2Q3, m22 = m2uc3, Nc;S = 3,  ,

,  , and A = yt(Atsinβ − μcosβ). In particular, the part of δλS that is polynomial in A, dropping terms of order g2, taking

, and A = yt(Atsinβ − μcosβ). In particular, the part of δλS that is polynomial in A, dropping terms of order g2, taking  , and assuming large enough tanβ, is

, and assuming large enough tanβ, is

with Xt = At − μcot β. This is the familiar result that can be found in, for example, [43]. As for the logarithmic term, tops contribute  , so the μ-dependence cancels and the leftover logarithmic correction is

, so the μ-dependence cancels and the leftover logarithmic correction is  , which is also of the familiar expected form.

, which is also of the familiar expected form.

3. Vacuum stability

Given the results of the Coleman–Weinberg calculation, it is apparent that trying to achieve a large enough loop correction to change the sign of the hGG coupling is a dangerous game. Flipping the sign implies having a particle with a mass that diminishes with increasing Higgs VEV, as can be seen from equation (2). One possibility for this is a mixing effect: either one has vectorlike fermions getting a majority of their mass independent of the Higgs, or scalars that mix analogously to the familiar case of stops in supersymmetric theories. In the case of fermions, the most dangerous effect is the renormalization group running from the fermion Yukawa coupling, which pushes the Higgs quartic toward negative values in the UV and can lead to an unstable vacuum [44]. For scalars, the RG effect is not dangerous, as the Higgs quartic is pushed toward larger values in the UV. However, there is a large negative threshold correction, proportional to the fourth power of the mixing parameter A (familiar from the case of stops), which threatens to make the Higgs tachyonic. Furthermore, such large mixing parameters can lead to color and charge breaking minima of the tree-level potential [45]. The remaining alternative, which does not require large mixings, is that one can have scalars with a positive mass2 and a negative quartic coupling to the Higgs. Such a negative quartic coupling again can lead to color- and charge-breaking minima or runaway directions. Our goal in this section is to give some simple estimates of the parameter space leading to catastrophic vacuum instabilities and show that most attempts to achieve an hGG coupling of approximately the SM magnitude but opposite sign are ruled out by them.

3.1. Inverting hGG with stops

Given that we are looking for large changes to the Higgs potential that require light new colored and charged particles, it is reasonable to first consider whether stops can be responsible, since naturalness of electroweak symmetry breaking (EWSB) in supersymmetric theories favors light stops [29, 30]. In the case of stops, the general results discussed in the previous section imply a correction to the hGG amplitude (specializing the general result equation (11)):

up to small D-term corrections (taken into account in the plots below). Here  and

and  are mass eigenvalues, not Lagrangian parameters. The effect of stops on Higgs branching ratios has been discussed in several papers in the recent literature [6, 17, 18, 24, 46], which reach a variety of conclusions. As emphasized by Blum et al [46], light unmixed stops tend to increase the hGG coupling and decrease the hγγ coupling, whereas highly mixed stops contribute large corrections to m2Hu (thus requiring more tuning for EWSB) and lead to large corrections to b → sγ that must also be tuned away. The same considerations led [24] to focus on the 'funnel' region in which the stop corrections to hGG are small. On the other hand, the authors of [18, 22] argued for light and highly mixed stops in the region with the inverted sign of hGG, which could improve the fit to data.

are mass eigenvalues, not Lagrangian parameters. The effect of stops on Higgs branching ratios has been discussed in several papers in the recent literature [6, 17, 18, 24, 46], which reach a variety of conclusions. As emphasized by Blum et al [46], light unmixed stops tend to increase the hGG coupling and decrease the hγγ coupling, whereas highly mixed stops contribute large corrections to m2Hu (thus requiring more tuning for EWSB) and lead to large corrections to b → sγ that must also be tuned away. The same considerations led [24] to focus on the 'funnel' region in which the stop corrections to hGG are small. On the other hand, the authors of [18, 22] argued for light and highly mixed stops in the region with the inverted sign of hGG, which could improve the fit to data.

We illustrate the parameter space that can achieve A(hGG) = −ASM(hGG) in figure 3. As is clear from equation (14), this occurs at very large values of the mixing parameter Xt. This leads to a large splitting between the two stop mass eigenstates. In this region of parameter space, the lightest stop eigenvalue tends to be fairly light. For example, pushing the light eigenstate up to 450 GeV implies 20 TeV A-terms, which is an enormously finely-tuned scenario, both from the point of view of EWSB and of b → sγ. In fact, from the Coleman–Weinberg discussion in section 2.3, one can readily see that such large A-terms lead to very large negative threshold corrections to the Higgs mass. This implies the need for very large beyond-MSSM couplings of the Higgs boson that are capable of lifting its mass up to 125 GeV. When such couplings become large enough, it is difficult to imagine that other Higgs properties remain unmodified, so that considering only stop-loop modifications to the partial widths is dubious. On the other hand, one may wonder if the lower-left corner of the plot, with a light stop eigenstate, can fit the data, with large but no longer unreasonably large A-terms. It is still rather tuned. Recent experimental searches for direct production of light stops [47–52] constrain much of the stop parameter space with  , but only for sufficiently light neutralinos. The more squeezed regime will be probed by a combination of traditional missing-ET

signatures [53–62] and spin correlations [63], and even the case of R-parity violation may be constrained soon [64]. Nonetheless, for the moment, these considerations still allow as a logical possibility that light, highly mixed stops significantly alter the Higgs properties.

, but only for sufficiently light neutralinos. The more squeezed regime will be probed by a combination of traditional missing-ET

signatures [53–62] and spin correlations [63], and even the case of R-parity violation may be constrained soon [64]. Nonetheless, for the moment, these considerations still allow as a logical possibility that light, highly mixed stops significantly alter the Higgs properties.

Figure 3. Stop parameter space that achieves a hGG coupling that is −1 times its SM value. This condition reduces the three-dimensional parameter space (mQ,mU,Xt) to two dimensions, which we parameterize with mQ and mU. At left: contours of the lightest stop mass (orange, dashed) and the value of Xt needed to achieve the desired coupling (purple, solid). At right: contours of the heavy stop mass (orange, dashed) and the corresponding stop mixing  parameterizing the right-handedness of the stop (purple, solid).

parameterizing the right-handedness of the stop (purple, solid).

Download figure:

Standard imageHowever, vacuum instability poses an even more serious problem for this scenario than fine-tuning. The large A-term mixing is a trilinear scalar coupling  , so the potential can acquire large negative values when all three of these fields have VEVs. Because the Higgs and one stop eigenstate are relatively light, the barrier separating our EWSB vacuum from a color- and charge-breaking minimum can be relatively low. At large enough field values, quartic couplings arising from the Yukawa coupling will prevent the potential from being unbounded from below, even in the D-flat direction where the stop and Higgs VEVs are equal. Nonetheless, a deep charge- and color-breaking vacuum will exist when the A-term is large. This is illustrated with contour plots of the potential in figure 4. It remains to check whether the vacuum decay to this deep minimum happens fast enough to rule out this scenario.

, so the potential can acquire large negative values when all three of these fields have VEVs. Because the Higgs and one stop eigenstate are relatively light, the barrier separating our EWSB vacuum from a color- and charge-breaking minimum can be relatively low. At large enough field values, quartic couplings arising from the Yukawa coupling will prevent the potential from being unbounded from below, even in the D-flat direction where the stop and Higgs VEVs are equal. Nonetheless, a deep charge- and color-breaking vacuum will exist when the A-term is large. This is illustrated with contour plots of the potential in figure 4. It remains to check whether the vacuum decay to this deep minimum happens fast enough to rule out this scenario.

Figure 4. Tree-level potential  along the subspace

along the subspace  . We have fixed mQ = mU = 800 GeV and adjusted Xt to produce A(hGG) = −ASM(hGG). The right-hand plot zooms in near the good EWSB vacuum where 〈h〉 ≈ 246 GeV and the stops have no VEV. A much deeper minimum is located near the D-flat direction where the Higgs and stop VEVs are all equal. The barrier separating the two minima is shallow.

. We have fixed mQ = mU = 800 GeV and adjusted Xt to produce A(hGG) = −ASM(hGG). The right-hand plot zooms in near the good EWSB vacuum where 〈h〉 ≈ 246 GeV and the stops have no VEV. A much deeper minimum is located near the D-flat direction where the Higgs and stop VEVs are all equal. The barrier separating the two minima is shallow.

Download figure:

Standard imageFor this calculation we use the tree-level potential for the up-type Higgs H and the third generation squark superfields:

We take  with mh = 125 GeV the measured Higgs mass. Here δλ represents the corrections required to achieve the appropriate measured Higgs VEV; we remain agnostic about what model generates these corrections (in particular, we do not tie them to the stop masses and the MSSM radiative corrections). In the plot in figure 4, we have taken the fields to be real valued, with

with mh = 125 GeV the measured Higgs mass. Here δλ represents the corrections required to achieve the appropriate measured Higgs VEV; we remain agnostic about what model generates these corrections (in particular, we do not tie them to the stop masses and the MSSM radiative corrections). In the plot in figure 4, we have taken the fields to be real valued, with  , and

, and  . We ignore the down-type Higgs; at large tanβ, it should not be important, and more generally we do not expect that it will qualitatively alter the results.

. We ignore the down-type Higgs; at large tanβ, it should not be important, and more generally we do not expect that it will qualitatively alter the results.

Because the results of [45] are expressed as a scatter plot of points that are viable or not, it is not possible to do a systematic check from their results of whether the parameter space for which the hGG amplitude is inverted (as displayed in figure 3) is ruled out. Thus, we perform a new numerical calculation of the zero-temperature tunneling rate, using a slightly modified version of the CosmoTransitions software [65].3 The result is depicted in figure 5. In the right-hand panel, one can see that a bounce action S0 ≳ 400, necessary for a sufficiently long-lived metastable vacuum to describe our universe, occurs only for a light stop mass eigenstate below 70 GeV. Such a light stop is excluded by LEP, even in the case of small  mass splitting [66, 67].

mass splitting [66, 67].

Figure 5. Contours of the bounce action S0 as calculated by CosmoTransitions [65]. The requirement for a sufficiently long-lived vacuum is S0 ≳ 400. The left-hand plot shows that the bulk of the parameter space fails this requirement by a wide margin. The right-hand plot zooms in on the low-mass region, overlaying contours of the mass of the light stop eigenstate  (orange, dashed). The bounce action exceeds 400 only when the light stop eigenstate is below 70 GeV, and thus cleanly excluded by LEP constraints.

(orange, dashed). The bounce action exceeds 400 only when the light stop eigenstate is below 70 GeV, and thus cleanly excluded by LEP constraints.

Download figure:

Standard image3.2. Inverting hGG with charged scalar color octets

Here we will consider a different possibility that does not involve large mixing effects. If we drop the assumption of supersymmetry, we can consider charged scalar octets that have a mass that decreases with increasing Higgs mass,

with λHO > 0. This is a simplified subset of the interactions that arise, for example, for the Manohar–Wise scalar in the (8, 2)1/2 representation of the SM gauge group [68]. Other interactions contract the SU(2) indices of H with those of O. There is no principled reason to ignore them, but we restrict to a low-dimensional parameter space for ease of plotting the results and because we expect it will capture the qualitative story of the interplay between vacuum stability and Higgs corrections. Quantitatively, it could be worthwhile to explore the full set of operators, but this is beyond the scope of this paper.

The Manohar–Wise representation contains both a neutral scalar O0 and a charged scalar O+; assuming they have the same mass, as they do with this simplified set of interactions with the Higgs, one finds that they affect the Higgs decay widths as shown by the dashed purple curve in figure 2, which comes rather close to the best-fit point of our simplified χ2 fit. Effects of such an octet scalar on the hGG amplitude were considered recently in [69–71] in the regime with relatively small corrections that would lead to a reduced gg → H cross section. The possibility that λHO < 0 could lead to a reasonable fit of the data with enhanced diphoton rate was observed in [72]. Furthermore, as emphasized in [73], this regime of parameter space makes a striking prediction of a di-Higgs production rate hundreds or thousands of times larger than the rate in the SM.

In this case, the condition ANP(hGG) = −2ASM(hGG), at one loop and ignoring m2O/m2H effects, singles out a particular choice of λHO given the mass m2O:

Taking into account the (small) m2H/m2O corrections, we plot the required choice of λHO as a function of m2O in figure 6 along with the physical mass of the octet. Notice that, unless the new octet state is very light, the coupling quickly becomes extremely large. In particular, once the physical octet mass reaches about 400 GeV, the coupling is nonperturbatively large. Hence, this scenario is only viable with relatively light states. In fact, the quartic part of the potential becomes unbounded below unless the condition

is satisfied. We have also plotted  in figure 6. It becomes nonperturbatively large already when mO ≈ 300 GeV, a point at which the physical mass is only about 180 GeV. Of course, a potential that is unbounded below does not, strictly speaking, exclude the theory; this requires a check of the tunneling rate from our metastable vacuum to the runaway part of the potential, as in the previous section. We show this tunneling rate in figure 7, which indicates that a value of λO a factor of 1.5–2 below

in figure 6. It becomes nonperturbatively large already when mO ≈ 300 GeV, a point at which the physical mass is only about 180 GeV. Of course, a potential that is unbounded below does not, strictly speaking, exclude the theory; this requires a check of the tunneling rate from our metastable vacuum to the runaway part of the potential, as in the previous section. We show this tunneling rate in figure 7, which indicates that a value of λO a factor of 1.5–2 below  can yield an unbounded-from-below potential that is metastable enough to be compatible with the age of our universe.

can yield an unbounded-from-below potential that is metastable enough to be compatible with the age of our universe.

Figure 6. Left: value of the Higgs–octet coupling required for a sign-flip of the hGG amplitude (light blue, solid) and of the corresponding minimum octet quartic coupling needed for a potential that is not unbounded below. Right: physical mass of the octet. The dotted red line at 185 GeV marks the lower bound on a sgluon mass from the ATLAS study [74], which may be taken as an approximate guide to the collider constraints on this scenario.

Download figure:

Standard imageFigure 7. The bounce action for tunneling away from the metastable minimum in the scalar octet case, as a function of the physical octet mass  and the octet quartic λO. The region below the dashed orange curve has a potential that is unbounded from below. Nonetheless, the tunneling calculation shows that a portion of this region is metastable enough to provide a viable vacuum. The vertical red dotted line is an estimate of the collider bound, showing that any surviving parameter space is at masses near 200 GeV and strong coupling λO ≳ 4, or must decay in a manner that evades the ATLAS paired dijet search. Kinks in the curves are from the parameter grid of the numerical scan, not physics.

and the octet quartic λO. The region below the dashed orange curve has a potential that is unbounded from below. Nonetheless, the tunneling calculation shows that a portion of this region is metastable enough to provide a viable vacuum. The vertical red dotted line is an estimate of the collider bound, showing that any surviving parameter space is at masses near 200 GeV and strong coupling λO ≳ 4, or must decay in a manner that evades the ATLAS paired dijet search. Kinks in the curves are from the parameter grid of the numerical scan, not physics.

Download figure:

Standard imageThe full Lagrangian of [68], including further operators such as H†aHbO†AaOAb (with a,b

SU(2)L indices and A an SU(3)c index) and Yukawa couplings of O to SM fermions, is beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, we will make brief remarks on collider bounds. Minimal flavor violation Yukawa couplings of O to the quark fields lead to dominant decays  and

and  (when this mode is kinematically accessible). However, in most of the mass range that is viable for flipping the hGG amplitude, the decay to tops will be shut off. In that case, the searches for paired dijet resonances performed by ATLAS [74] and CMS [75] are likely the most sensitive probes of the scalar octets. (However, depending on the splitting within the SU(2)L multiplet, searches relying on leptons may also set bounds [69].) The CMS dijet resonance study only constrains states above 320 GeV, due to the relatively hard cuts required by high-luminosity running. The ATLAS study relied on early data with lower trigger thresholds, and bounds sgluons to be heavier than 185 GeV. Because we have multiple octet states, it is possible that the bound is stronger, but this conclusion depends on details of the branching ratios of our octets. Rather than undertake a full study of the collider bounds, we show the 185 GeV bound in figures 6 and 7 as a rough guideline. This shows that the viable parameter space is in a narrow range of masses above the bound and at strong coupling λO ≳ 4, unless the octet decays in a way that evades the ATLAS search. A more detailed discussion of constraints on Manohar–Wise octet scalars may be found in [76]. Another recent update on collider bounds is in [77].

(when this mode is kinematically accessible). However, in most of the mass range that is viable for flipping the hGG amplitude, the decay to tops will be shut off. In that case, the searches for paired dijet resonances performed by ATLAS [74] and CMS [75] are likely the most sensitive probes of the scalar octets. (However, depending on the splitting within the SU(2)L multiplet, searches relying on leptons may also set bounds [69].) The CMS dijet resonance study only constrains states above 320 GeV, due to the relatively hard cuts required by high-luminosity running. The ATLAS study relied on early data with lower trigger thresholds, and bounds sgluons to be heavier than 185 GeV. Because we have multiple octet states, it is possible that the bound is stronger, but this conclusion depends on details of the branching ratios of our octets. Rather than undertake a full study of the collider bounds, we show the 185 GeV bound in figures 6 and 7 as a rough guideline. This shows that the viable parameter space is in a narrow range of masses above the bound and at strong coupling λO ≳ 4, unless the octet decays in a way that evades the ATLAS search. A more detailed discussion of constraints on Manohar–Wise octet scalars may be found in [76]. Another recent update on collider bounds is in [77].

3.3. Inverting hGG with new fermions

Having explored the effects of scalars that change the sign of hGG with large mixing effects or with negative quartics, and shown that there are vacuum stability problems in both cases, we should make some remarks on the case of fermions. Because qualitatively similar observations were made recently in [44], we will be brief. The essential point is that new color triplet fermions with Yukawa couplings to the Higgs contribute terms  in the renormalization group equation (RGE) for the Higgs quartic. These corrections drive λ negative at relatively low energies, leading to yet another vacuum instability. Of course, there is a way out: if the new colored fields come in complete supermultiplets, the scalars contribute an opposite contribution to the running of λ and the quartic can be saved from turning negative. Thus, one perspective on this correction is that it gives a bound on the size of the allowed splitting between fermions and scalars in the new multiplet; this is essentially the naturalness point of view discussed in [44].

in the renormalization group equation (RGE) for the Higgs quartic. These corrections drive λ negative at relatively low energies, leading to yet another vacuum instability. Of course, there is a way out: if the new colored fields come in complete supermultiplets, the scalars contribute an opposite contribution to the running of λ and the quartic can be saved from turning negative. Thus, one perspective on this correction is that it gives a bound on the size of the allowed splitting between fermions and scalars in the new multiplet; this is essentially the naturalness point of view discussed in [44].

The first observation relates to fermionic top partners. In particular, suppose we have new fields  in the (3,1)±2/3 representations of the SM gauge group. We can add both a vectorlike mass for these fields and a mixing term with the SM left-handed quarks,

in the (3,1)±2/3 representations of the SM gauge group. We can add both a vectorlike mass for these fields and a mixing term with the SM left-handed quarks,

Such top partners contribute a correction to the hGG amplitude:

If we wish this to equal −1, we must take  . If the new colored states are to be heavier than the top quark, this requires large Yukawas. Furthermore, these states are highly mixed with the top, and require that we significantly alter yt from its SM value. This is an awkward solution that will be difficult to reconcile with experimental bounds.

. If the new colored states are to be heavier than the top quark, this requires large Yukawas. Furthermore, these states are highly mixed with the top, and require that we significantly alter yt from its SM value. This is an awkward solution that will be difficult to reconcile with experimental bounds.

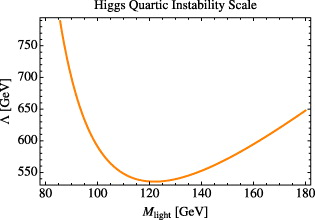

A safer approach is to add a pair of vectorlike fermions, as in section 2.2, which are not mixed with the SM top. To be concrete, we will take these states to have the same quantum numbers as the SM Q and uc fields, but with a parity that prevents mixing terms with the SM. Furthermore, we will simplify the story by taking mχ = mψ = M and y1 = y2 = y. Obtaining the amplitude A(hGG) = −ASM(hGG) then requires that  , with mass eigenvalues about Mlight ≈ 0.29M and Mheavy ≈ 1.7 M. The finite correction to λ (which must have a value of about 0.13 for the correct Higgs VEV) from the Coleman–Weinberg formula can then be expressed as

, with mass eigenvalues about Mlight ≈ 0.29M and Mheavy ≈ 1.7 M. The finite correction to λ (which must have a value of about 0.13 for the correct Higgs VEV) from the Coleman–Weinberg formula can then be expressed as  , so that as we raise the mass scale of the new colored fermions relative to the top mass, the tuning in the Higgs sector increases quartically.

, so that as we raise the mass scale of the new colored fermions relative to the top mass, the tuning in the Higgs sector increases quartically.

Finally, we give an approximate solution of the RGEs to see at what scale Λ the Higgs quartic drives the potential unstable, when  (with H0 the Hubble constant), as in [44]. The Hubble scale appears in this estimate because we are asking if the bounce is rapid relative to the age of the universe, and the other numerical factors arise from a simple approximation that the bounce action is ≈8π2/(3|λ|), as explained in [78]. For simplicity we have dropped terms in the RGEs proportional to g1, which do not significantly change the results. We begin at the

(with H0 the Hubble constant), as in [44]. The Hubble scale appears in this estimate because we are asking if the bounce is rapid relative to the age of the universe, and the other numerical factors arise from a simple approximation that the bounce action is ≈8π2/(3|λ|), as explained in [78]. For simplicity we have dropped terms in the RGEs proportional to g1, which do not significantly change the results. We begin at the  top mass in the SM, run up to the scale M using SM beta functions, and then run to higher energies with the new physics beta functions, turning on y1 = y2 at M. In this case, denoting the common value of y1 and y2 simply as y, the beta functions are altered as:

top mass in the SM, run up to the scale M using SM beta functions, and then run to higher energies with the new physics beta functions, turning on y1 = y2 at M. In this case, denoting the common value of y1 and y2 simply as y, the beta functions are altered as:

The result of integrating the RGEs is shown in figure 8. The rising curve at Mlight ≳ 120 GeV approximately tracks the value of M ≈ 3Mlight, indicating that λ runs negative essentially immediately when we turn on the RG effects of the new states. A better calculation would correctly take into account the running between the thresholds Mlight and Mheavy, but this plot makes our qualitative point: if new fermionic states are to change the sign of the hGG amplitude, not only do they imply an uncomfortably large amount of fine-tuning and strong coupling, but their superpartners must be nearby. Otherwise, they are ruled out by a catastrophic vacuum instability, much like the scalar cases we have studied.

Figure 8. An approximation to the scale Λ at which an instability in the Higgs potential sets in, as a function of the light fermion mass eigenstate Mlight. See the text for an explanation.

Download figure:

Standard image4. Discussion

We have seen that, in any region with large enough radiative corrections from loops of new colored and charged particles to flip the sign of the hGG amplitude, there are significant modifications to the Higgs potential and potentially dangerous radiative effects. In particular, the most appealing such scenario, with loops of stop squarks, is ruled out by rapid vacuum decay to color- and charge-breaking minima. In the case of a color octet scalar with a negative quartic coupling to the Higgs, the combination of vacuum decay bounds and collider constraints rules out much of the parameter space. However, a light octet scalar around 200 GeV with a large self-coupling may still be allowed. This loophole could likely be closed by a more thorough analysis, or by further collider searches. Fermionic states are only allowed if they are part of a supermultiplet with the scalar states nearby.

In the scalar cases, one could ask whether adding new terms to the potential, beyond those we have considered, could lift the dangerous minima and render the A(hGG) = −ASM(hGG) scenario viable after all. However, a local change in the potential far from the good EWSB vacuum is unlikely to have much effect, since in the stop case the tunneling is to a very deep minimum, and in the octet scalar case to a runaway direction. In both scenarios, the fundamental problem is that a relatively low barrier separates the vacuum that could represent our universe from a steep downhill plunge. Any physics that could make this viable has to change the potential near our vacuum, making the shallow hill in the potential into a sizable barrier. This likely requires new strong coupling, and although such models would have to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis, it seems unlikely that a model that could achieve this would not also alter Higgs production or decay in other ways, rendering the original motivation moot.

A safer scenario to fit possible deviations in the data is to rely on loop corrections of charged color-singlet particles to enhance the hγγ rate. This has received attention recently in [44, 79–84]. In the scenarios involving new scalars, it may be worthwhile to do a careful scan for charge-violating minima and tunneling rates that could constrain the parameter space in a similar way to that we discussed here. The various difficulties with tuning and vacuum instabilities arise simply because achieving large effects with loops requires venturing into extreme regions of parameter space. (A distinctive scenario in which the correct sign of the amplitude arises is from loops of new charged gauge bosons [81, 85, 86].) If the LHC observations continue to indicate substantial deviations in Higgs properties, it may mean that the effect arises at tree-level, which is easily achieved by non-decoupling effects of further Higgs states [14, 87–92]. Searching for such states should continue to be a central part of the LHC's ongoing investigation of the nature of EWSB.

Acknowledgments

I thank Patrick Meade for useful discussions that helped to initiate this project, and Max Wainwright for helpful correspondence regarding the CosmoTransitions software. I also thank Haipeng An, JiJi Fan, Christophe Grojean, Veronica Sanz and Mike Trott for interesting discussions or correspondence, and Mike Trott for comments on the draft. A portion of this work was carried out while visiting the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Research at Perimeter Institute is supported by the Government of Canada through Industry Canada and by the Province of Ontario through the Ministry of Economic Development & Innovation. This work was also supported in part by the Fundamental Laws Initiative of the Harvard Center for the Fundamental Laws of Nature.

Appendix.: Details of the Coleman–Weinberg calculations

Footnotes

- 1

Here Rt denotes the ratio of the Higgs–top–top coupling to that predicted in the SM, assuming the top mass is chosen to be a positive real number.

- 2

A note on conventions: we will follow [33] in taking v ≈ 174 GeV. Our choices are such that yt ≈ 1,

, and

, and  .

. - 3

The main change was to replace a call to scipy.optimize.fmin with one to scipy.optimize.fminbound to prevent a minimum-finding step from skipping over a shallow minimum and falling into a deep one.