The right to conduct missionary activities and ask for donations is a necessary part of freedom of religion or belief. Unduly restricting it violates international law.

by Patricia Duval

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

It should be underlined that the right to spread one’s faith and proselytize is inherent to the right to manifest one’s religious beliefs and is protected as such.

Former Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Heiner Bielefeldt, devoted part of his 2012 Interim report to the Human Rights Council to “the right to try to convert others by means of non-coercive persuasion” and reported that some “States impose tight legislative or administrative restrictions on communicative outreach activities. This may unduly limit the right to try to convert others by means of non-coercive persuasion, which itself constitutes an inextricable part of freedom of religion or belief” [emphasis added].

The Special Rapporteur added that “many such restrictions are conceptualized and implemented in a flagrantly discriminatory manner,” and that “members of religious communities that have a reputation of being generally engaged in missionary activities may also face societal prejudices that can escalate into paranoia” (13 August 2012, A/67/303; emphasis added).

The High Court of Tokyo, in a decision of 13 May 2003 cited by MEXT amongst the thirty-two tort cases supporting its dissolution request, ruled as follows: “The plaintiffs were then led to participate in a series of seminars (workshop) or training sessions and other activities in stages, allowing the doctrines, Divine Principle, to gradually permeate their understanding. Furthermore, under the name of practicing the doctrine, they were engaged in specific missionary and economic activities. Even when the plaintiffs began to harbor doubts about the process by which they were recruited or the activities they were currently engaged in, they were made to believe that abandoning their faith would result in them and their entire family being deprived of salvation in this world. This created a psychological barrier, making it difficult for them to leave the UC” (High Court of Tokyo, page 6, upholding the ruling of the Niigata District Court of 20 October 2002, page 147; emphasis added).

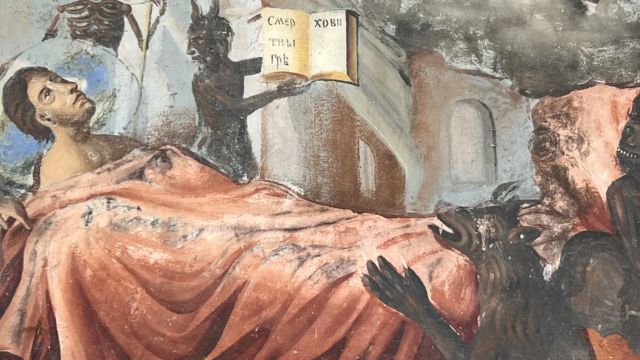

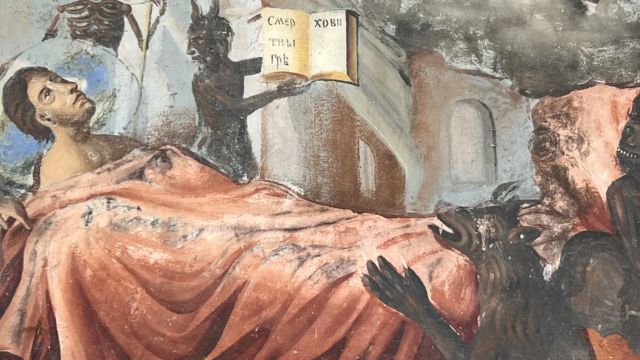

As afore-mentioned, the concepts of hell and salvation can be found in traditional religions and the alleged difficulty to leave the religion due to these beliefs does not constitute coercion in the spreading of the faith.

There is no doubt that the invitation by Unification Church members for newcomers to participate in seminars or training sessions “allowing the doctrines, Divine Principle, to gradually permeate their understanding,” falls into the category of “non-coercive persuasion” and legitimate proselytism.

It is therefore protected as part of the manifestation of religion or belief under Article 18 of the Covenant.

The same goes with the right to solicit donations to establish and maintain religious institutions.

The UN General Assembly spelled out this right in its “Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief” on 25 November 1981 (General Assembly Resolution 36/55).

The Declaration provided: “Art. 6 (b): The right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief includes the freedom, ‘to establish and maintain appropriate charitable or humanitarian institutions’… Art. 6 (f): The right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief includes the freedom, ‘to solicit and receive voluntary financial and other contributions from individuals and institutions.’”

It is therefore totally legitimate for Unification Church members to solicit donations and other contributions for the functioning of the Church, as long as they are not extorted by force and violence.

Actually, violence in the present case has not been exerted by the Unification Church but by the deprogrammers who coerced the believers into recanting their faith and then suing the Church to prove their apostasy.

The courts have been biased in their rulings against the UC, assuming that the solicitation of donations was only motivated by profit-making and considering the spreading of the faith as a tool of mental manipulation and a mere cover for duping potential donors.

And the Japanese authorities, through the application for dissolution by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (“MEXT”), have infringed their duty of neutrality and voluntarily violated the right of Unification Church members to manifest their faith, which they deemed not “socially acceptable.”

In conclusion, for all the reasons detailed above, the request from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) for a court order to dissolve the religious corporation of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification should be rejected.

It entails numerous violations of international human rights law, and infringes the commitments made by Japan to protect fundamental rights and freedoms.

Note: This legal analysis should be read in conjunction with the author’s previous report “Japan and the Unification Church: The Duval Report,” published by “Bitter Winter” in five installments: