SHANGHAI/NEW YORK -- At 24 years old, Zhang Ru is not a target customer of the Shanghai community dining hall where she has become a regular. Clean and brightly lit, the eatery typically caters to the elderly with its cheap meals of stir-fried Chinese cabbage and braised pork belly.

But over the past year, the place has become a frequent haunt for Zhang. "Eating here gives me better value for money," said the new recruit at a software company. "It helps by keeping my food bills below 100 yuan ($14) daily," she added, stressing she needs to save for the future.

A waitress at the dining hall said that these days, young people like Zhang make up about a third of the clientele.

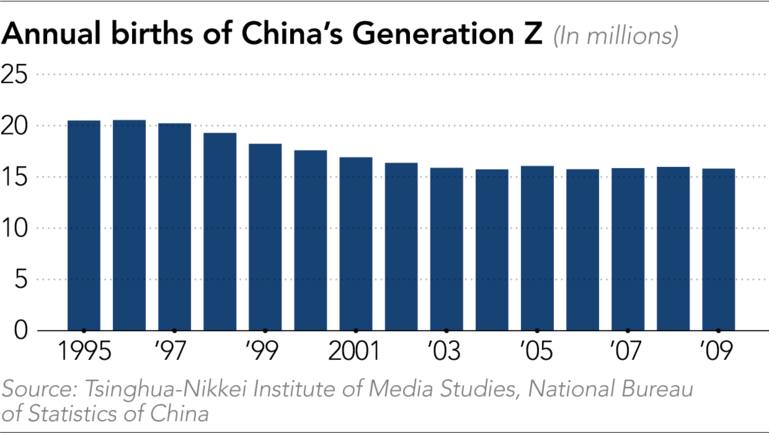

Zhang is one of the Chinese between the ages of 15 and 29, labeled Generation Z, who have become something of an obsession for marketers and policymakers alike. They account for 18.4% of the population of 1.4 billion, according to a joint study published this year by the Tsinghua-Nikkei Institute of Media Studies, and hold the key to future consumption and child rearing.

But they simultaneously face the burdens of economic uncertainty and an aging society. While China's first-quarter gross domestic product grew 5.3% on the year, beating expectations, most forecasts point to a continued slowdown in the coming years. Meanwhile, the jobless rate among people ages 16 to 24 stood at 15.3% in February, well above the national average of 5.3%.

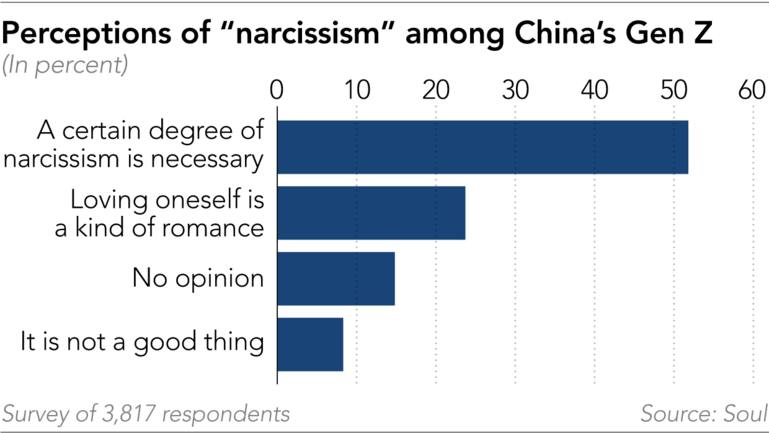

Gen Z's habits, and the pressures that shape them, will affect the world's No. 2 economy for years to come. "Reverse consumption" and the "stingy economy" are now buzzwords on Chinese social media, reflecting how young people raised in an era of rapid economic expansion and rising living standards are adopting a more rational approach to spending. Another term gaining traction is "narcissism," which is interpreted not as "selfishness" but as a positive form of self-care and self-acceptance.

None of this should be misunderstood as an echo of anti-consumerist movements in the West, said Biao Xiang, an anthropologist who researches China at Germany's Max Planck Institute. "In China, it is driven by a sense of uncertainties about the future, a deep sense of doubt and disillusionment about the promise given since [they were] young," he said.

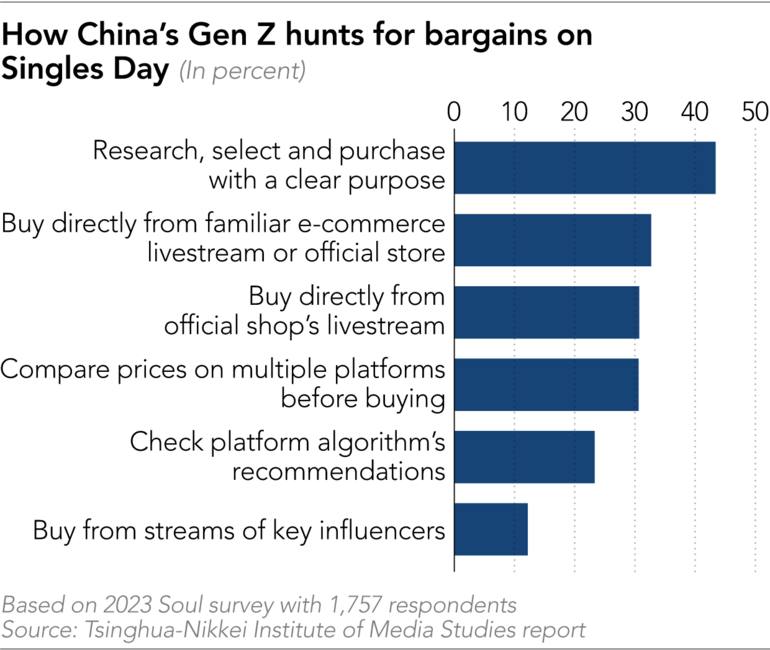

Those fears and disappointments manifest in various ways, including consumers scouring e-commerce platforms for discounts. Due to restrictions on Western apps, this largely happens within a domestic ecosystem of apps like Xiaohongshu, known as China's answer to Instagram, and TikTok's Douyin. The Tsinghua-Nikkei study on Gen Z habits, citing a survey by the Chinese social media platform Soul, noted that for the Singles Day shopping festival, 43.4% of them research and select purchases with a clear purpose and over 30% compare prices on multiple platforms before buying.

Soul, whose user base is about 80% Gen Z, has identified the value-for-money lifestyle and narcissism as major trends for 2024. Other keywords highlighted in its reports on Gen Z include "lazy health," describing a desire for low-cost methods of improving well-being such as getting enough sleep; "city walks," or aimless strolls around town; and "special forces travel," which refers to short and intense trips that maximize activities while minimizing time and money spent.

"With the rise of the stingy economy, activities like dining at community canteens and shopping at discount snack stores have become popular money-saving strategies," observed Julienna Law, managing editor at Jing Daily, a media outlet focused on consumer trends.

For Catherine Lin, who works at a solar cell producer in the eastern city of Ningbo, the bargain hunting includes cake.

"I love cakes but I don't usually buy them because they're expensive and could make me fat," said Lin, 30. Postings on Xiaohongshu about "leftover mystery boxes" -- unsold food from restaurants, grocery stores and bakeries -- piqued her curiosity. The boxes, sold via the WeChat messaging app, are a riff on the Too Good to Go service created in Denmark to minimize food waste.

Lin has ordered several mystery boxes, saving 20 to 30 yuan on average. She said she paid 15.9 yuan for a piece of cake that normally would have cost her 37 yuan.

Such services appeal to young consumers' desire for sustainability, not just frugality. But their emphasis on saving yuan is part of a complex puzzle for Chinese government officials, who are attempting to ease persistent deflation fears and maintain gross domestic product growth at an annual clip of "around 5%."

Household spending remains sluggish, as an uneven post-COVID recovery and a prolonged property slump have shaken confidence. Retail sales growth slowed to 5.5% on the year in the first two months of 2024, down from 7.4% in December.

"It is worth noting that the degradation of consumption has far-reaching ramifications for the economy," said Yong Chen, an expert on the tourism economy at EHL Hospitality Business School in Switzerland. As an example, Chen pointed to more people ordering takeaway rather than dining out "because it is cheaper and more convenient," warning of a potentially devastating impact on the restaurant sector.

The consumption slump could even have geopolitical implications. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen earlier this month prodded Beijing to do more to persuade citizens to spend, rather than save, to absorb industrial overcapacity that is flooding global markets.

Jing Daily's Law agreed that the shift in consumer behavior is already changing markets. She cited the rise of Pinduoduo, which is known for its dirt-cheap products and has challenged the dominance of Alibaba Group Holding.

The quest for deals coincides with a growing preference for local goods. The Tsinghua-Nikkei report on Gen Z noted Soul's finding that 59% favor locally made brands, against 11.8% preferring foreign ones.

Some international luxury brands are showing resilience in China thanks to a base of wealthy customers who are less affected by the slowdown. But the Kering group, which manages a slew of big fashion names, last month issued a profit warning that it blamed on "a steeper sales drop at Gucci, notably in the Asia-Pacific region."

Law sees brands adjusting their tactics. "Rather than directly releasing products targeted toward budget-conscious consumers, luxury brands are choosing to collaborate with more affordable brands to create products or experiences that cater to a wider range of shoppers," she said.

Law said a good example is the MoonSwatch, a wristwatch released in 2022 as a collaboration between the luxury Omega brand and the mass-market Swatch, both of which belong to Switzerland's Swatch Group. The watch borrows the design of the Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch -- known as the timepiece of the first astronauts to step on the moon -- but sells for a fraction of the cost. While the watch is sold globally, China is one of the group's key markets.

Nevertheless, Swatch CEO Nick Hayek told a Swiss newspaper late last month that the Chinese market would "remain difficult" this year because consumers have "become more price-sensitive."

Xiang, the anthropologist, said there are likely limits to how low Gen Z spending will go, as many can count on the savings of their parents. The "self-love" or "narcissism" phenomenon worries him more, as he fears it runs "deeper" than an economic problem and reflects social isolation.

In another poll in December, Soul found that over 90% of more than 3,800 users did not regard "narcissism" as a negative thing, and nearly a quarter considered loving oneself to be a type of "romance."

Xiang observed that "Gen Z probably had the happiest childhood, material-wise, in Chinese history" but as they grew older also went through "tremendous mental stress" under the weight of parents' expectations for them to do well economically and socially. Now he worries that many are turning inward -- just as Chinese policymakers try to mitigate low marriage and birth rates after the country recorded its second straight annual population decline in 2023.

"In social isolation, people fear love," Xiang said. "Love is the ultimate joy of life, but for many young people it is a burden because one will need to spend time with his or her partner and read the partner's emotion."

The shifting buzzwords, from the "lying flat" rejection of economic pressure seen in recent years to reverse consumption and self-love, suggest a generation searching for a path under trying circumstances.

On the home-sharing reservation operator Xiaozhu, searches for "temple" by Gen Z users surged by a factor of 24 during the recent Lunar New Year period.

Temple stays have become a popular alternative to hotels as a budget option with a spiritual bonus. A night's stay can cost around 80 yuan ($11), including early morning meditation sessions.

The temple accommodations appeal to young people like Shirley Zuo, who quit her job only to grow fearful for her future. Last year, she spent a night in a monastery in Chang'an, in northern China, as a volunteer. The getaway, she said, was her way of seeking an environment "to think and to see if I could figure out something for myself."

Chinese policymakers, meanwhile, will be trying to figure out how to ensure the young generation earns enough yuan and is willing to spend it.