Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

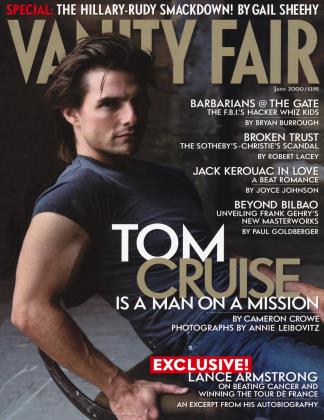

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowChristopher Davidge's parting shot as Christie's C.E.O., before he left for India with a beautiful young employee, was to provide evidence that the venerable auction house may have fixed prices with rival Sotheby’s. Davidge’s motives—revenge for being derided as "the butler”? the amnesty he and his firm would receive?—are unclear. But, as ROBERT LACEY reports from New York, London, and Palm Beach, the resulting anti-trust case against Sotheby’s has derailed the career of C.E.O. Dede Brooks, shaken the social standing of controlling shareholder Alfred Taubman and his wife, Judy, and temporarily turned a laconic prosecutor from Brooklyn into the most powerful man in the art world

June 2000 Robert Lacey Jonathan BeckerChristopher Davidge's parting shot as Christie's C.E.O., before he left for India with a beautiful young employee, was to provide evidence that the venerable auction house may have fixed prices with rival Sotheby’s. Davidge’s motives—revenge for being derided as "the butler”? the amnesty he and his firm would receive?—are unclear. But, as ROBERT LACEY reports from New York, London, and Palm Beach, the resulting anti-trust case against Sotheby’s has derailed the career of C.E.O. Dede Brooks, shaken the social standing of controlling shareholder Alfred Taubman and his wife, Judy, and temporarily turned a laconic prosecutor from Brooklyn into the most powerful man in the art world

June 2000 Robert Lacey Jonathan BeckerChristie’s thought they had it in the bag—the $10 million estate of Lloyd H. Smith of Palm Beach: a Cezanne, a couple of Renoirs, a pair of George III tables, and a treasure chest of jewels. The prize of the jewelry collection was an extraordinary Cartier sapphire-and-diamond bracelet, 182 diamonds surrounding seven huge, cushion-shaped Kashmir sapphires of beautiful, violet sleepiness.

Sotheby’s also wanted the collection. For both auction houses the Smith estate would provide a useful start for their first art, jewelry, and furniture sales of the millennium. But Christie’s reckoned they had the inside track, since old Mr. Smith, a widower, had been cared for with unfailing devotion in his declining years by Helen Cluett, Christie’s energetic and well-connected senior stateswoman in Florida. Back in the 80s, Cluett had muscled Sotheby’s aside in order to put Christie’s on the map in Palm Beach.

Helen Cluett and Lloyd Smith were fixtures on the Palm Beach social calendar, Helen wheeling the old man to the smartest parties. She was an established and valued friend of the family. When Helen entertained, Lloyd occupied the room of honor in his wheelchair.

After Lloyd Smith’s death in October 1999, the executors set Wednesday, January 26, as the date for the “pre-auction auction” between the two houses in Palm Beach. Christie’s would make their pitch between one and three P.M. Sotheby’s had from four until six o’clock. Christie’s team featured their Geneva-based international jewelry chief, Francois Curiel.

Then the weather intervened. On the afternoon of January 25, heavy snowstorms began to blanket the Northeast. The Sotheby’s pitch group of six were all booked on flights out of New York the next morning, but it was obvious that the flights would get canceled or at least delayed. Chartering a private jet was the only way.

“A jet!” hisses one of the Christie’s team through gritted teeth.

As is usual for such bidding contests, each team arrived with a mock-up brochure, a schedule of estimates, and detailed promotion plans, but the private jet seemed to make a particular impression. “God,” sighed a Sotheby’s vice president, “was on our side.” Once Sotheby’s had declared how much they would spend promoting the collection, they had the deal, and the executors announced it the next day.

It was a classic coup in the thrust and counterthrust of rivalry between the two houses, and Christie’s chairman, Stephen Lash, was philosophical about it. “We just can’t possibly afford it,” he explained, trying to console Helen Cluett.

What Lash did not tell his Florida lieutenant was that the capture of the Smith estate was by no means Christie’s chief priority in late January. In New York, Christie’s was concluding a dangerous set of negotiations with the U.S. Justice Department which threatened the very future of the auction house and which would soon wipe the smile off the face of everyone at Sotheby’s. Christie’s had handed federal investigators material indicating that the two firms may have violated anti-trust regulations.

The art-auction world could never be the same again, and the bombshell stemmed from a file of papers deposited with the auction house’s lawyers by its retiring chief executive, Christopher Davidge.

Davidge was installed as managing director of Christie’s U.K. in 1985 with a briefing of exquisite condescension by one of the senior partners, an Old Etonian. “Well, Davidge,” he was told, “it’s like horse breeding. Every now and again the thoroughbreds get too refined and you need to bring in an old broodmare to give some toughness to the breed. I see you as the old broodmare.”

With his blow-dried hair, his chunky gold bracelet watch, and his too sharply pressed trousers, Davidge was the object of many a sly joke among the Old Guard at Christie’s. They called him “the butler,” though Davidge actually had a most respectable Christie’s pedigree. His grandfather, his father, and his mother had all been employees of the firm.

But the Davidges had worked in clerical and administrative positions, and that placed them in social Siberia. Davidge’s father, Roy, rose to become company secretary, but he was never rewarded in the same way as the partners. “The chap next door who worked as a butcher’s assistant earned more than my father,” recalled Davidge in a rare on-the-record interview with London’s Sunday Telegraph. “I was very anti-Christie’s when I was growing up.”

In the last few months, Internet sites have sprung up where you can sign on to sue the auction giants.

Having lived in public housing in London’s Maida Vale and attended the local St. Marylebone Grammar School, young Davidge was struck by the contrast between the upstairs-downstairs snobbery that had stunted his father’s life and the social mobility of his schoolmates, many of whom were Jewish. “Background did not mean a thing,” he remarked of them. “Anybody could do anything.”

So he joined a Jewish youth club, converted to Judaism, and married a Jewish girl. Rejecting his father’s pitch for him to join the firm, he worked for a real-estate agent, then tried his hand as a barrow boy in Petticoat Lane, selling men’s wear from a cart. “I made more in a day,” he later boasted, “than my father did in a week.”

As they ponder Davidge’s role in recent events, some Christie’s insiders have taken to wondering darkly if the barrow boy ever got over his youthful anger at the company that had treated his family with such disdain. But that was not how things seemed when he joined the organization in 1965 as a 20year-old trainee printer at White Brothers, a firm that Christie’s had acquired to print their catalogues. Within 15 years he was running the printing firm, winning the respect of the experts for his ability to get catalogues printed ahead of the enemy, and moving on to take control of the auction house.

It was not long before Sotheby’s noticed a new bite in the opposition. Through the boom of the late 1980s— and, more significantly, through the recession of the early 90s—Christie’s started pulling off some remarkable coups, setting price records that stand to this day: the most expensive picture ever sold at auction (van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet, $82.5 million, 1990), the most expensive piece of furniture (the Badminton cabinet, $15.1 million, 1990), the most expensive drawing (Raphael’s Study for the Head and Hand of an Apostle, $8.7 million, 1996), and the most expensive book or manuscript (a Leonardo da Vinci codex, sold in November 1994 to Microsoft’s Bill Gates for $30.8 million). By the end of 1994, Christie’s was splitting the market almost 50-50 with its ancient rival, whereas Sotheby’s had had a 60-40 advantage before the advent of Christopher Davidge.

Davidge got his results through promoting fresh talent and pruning deadwood, thereby prompting grumbles that he was settling old scores. “You filthy little printer!” yelled the grandson of a former partner as he was shown the door.

The ex-printer was unrepentant. Christie’s, he later told the Financial Times, was “like the Conservative Party, full of pomposity, arrogance, filled with people from a narrow social circle, who were not commercially aware. They recognized that the place needed a manager, but wanted to limit my involvement to below stairs.”

Davidge’s principal ruthlessness was directed at Sotheby’s. His goal (finally achieved in 1996) was to make Christie’s No. 1, and he did this by slashing Christie’s sales commission—the auction house’s charge to sellers—down to zero. For income, he trusted to the buyer’s premium that the auction house levies on successful bidders—$4 million, for example, on a $40 million Picasso—and to attract such high-ticket items, he was ready to put out the extra dollar, wooing consignors with lavish expenditures on travel, entertainment, and publicity campaigns. But these heavy costs were all recorded in the books as “marketing expenses,” so when Christie’s released their figures in their record-breaking years, they had remarkably little profit to show for all the extra business they were pulling in.

Sotheby’s grumbled that Davidge was purchasing market share at the expense of profitability. But to maintain their position they were forced to follow suit, and that had a similarly negative impact on their profits. By the start of 1995, both houses were cutting their sales commissions so fiercely that something had to give.

“It was desperation time,” remembered Robert Woolley, the Sotheby’s decorative-arts expert. “What it came down to was how many ways you could find to say ‘zero.’”

In the spring of 1995, the two enemies announced that they had decided to sheathe their swords—at least when it came to sales commissions. Christie’s went first, publishing on March 9 a new, non-negotiable scale of rates that went from 10 percent down to 2. Never, swore Davidge, would sellers get away with anything less. A month later Sotheby’s followed suit, publishing a very similar list of charges, with the refinement that these rates would be tied to the amount of business the individual seller placed with the auction house each year.

At the time, the linked announcements were seen as reflections of mutual exhaustion and harsh business reality—a joint realization that the bloodletting had to stop. But now, the art world is in turmoil because of the hidden and more sinister explanation that has been made public, and that disclosure is the work of Christopher Davidge.

In December of last year, Davidge concluded his personal severance negotiations with Frangois Pinault, the French tycoon who had purchased Christie’s in 1998. Davidge ended nearly 35 years with the auction house. As he cleared his desk and went off for Christmas, he pronounced himself “an extremely happy chappie” at the size of his parting settlement, which, at more than $10 million, dwarfs the combined remunerations of his father and grandfather for all their long years of bondage.

The cost of the class-action suits against Christie s and Sotheby’s could run to tens of millions of dollars.

The Davidge clan had finally gotten their payoff, and the 54year-old retiring chief executive had an extra bonus—Amrita Jhaveri, an attractive, 29-year-old expert from Christie’s 20th Century Indian Art Department, who went off with her former boss to India. Davidge’s first marriage had ended many years earlier—a victim, he once candidly admitted, of his seven-days-aweek work habit—and he had more recently separated from Olga Vislascheva, his second wife, a glamorous former model from Moscow 11 years his junior.

Davidge’s parting gift was a file of notes and papers which he left behind for Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, Christie’s U.S. law firm, to study, and when the lawyers realized what the documents contained, they lost no time in beating a path to the U.S. Justice Department. While Christie’s painting and jewelry experts were pondering their bid for the Lloyd Smith estate, senior management were huddled in legal consultations. On January 28, 2000, Christie’s started making confidential phone calls to major clients to inform them that the auction house was cooperating with a government investigation of antitrust violations and had been granted conditional amnesty by the Justice Department.

The violations related to the auction houses’ linked announcements of new commission charges back in 1995—around which, it now appeared, suspicions of collusion hovered. According to allegations filed this March in class-action suits in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York—denied by Sotheby’s on April 12 but not, to date, contested by Christie’s—the Davidge papers contained details of communications between the most senior executives of both Sotheby’s and Christie’s to discuss how the two houses could stop undercutting each other. Those named included Davidge and former Christie’s chairman Sir Anthony Tennant, along with Sotheby’s chairman and controlling shareholder A. Alfred Taubman and C.E.O. Dede Brooks. The two sides had talked, it was alleged, in secret meetings and “surreptitious” telephone calls to arrange their new scales of sales commissions in 1995—and were even said to have held earlier discussions about the buyer’s premium, which both houses had raised and set at the same rate within a few months of each other back in 1993. If proved, these hidden contacts would constitute an illegal conspiracy in restraint of trade, carrying Sherman Act penalties of up to $10 million in fines for a corporation or $350,000 for an individual, or up to three years’ imprisonment, or both.

Christie’s prompt cooperation with the Justice Department earned the auction house—and Davidge—amnesty from anti-trust prosecution. In the jargon of the anti-trust world, Christie’s had “ratted.” They had taken advantage of the provision that the first conspirator to turn in evidence of collusion may be granted amnesty.

This put the pressure on the opposition. News of Christie’s immunity and of the apparently incriminating documents led to a flurry of boardroom consultations at Sotheby’s. On February 21, Alfred Taubman and Dede Brooks resigned their executive positions, and Sotheby’s later announced that the pair would also be surrendering their directorships. Brooks resigned her position on the board of Morgan Stanley Dean Witter and put her $4 million Greenwich, Connecticut, house on the market.

The question now being asked at both auction houses is: why did Chris Davidge throw his bombshell? He could quietly have shredded his embarrassing file of papers and just walked away.

The simple explanation is that as long as the compromising papers were Davidge’s secret they were Davidge’s problem. Now they have very definitely become the problem of Christie’s—and, still more, of Sotheby’s.

But those who disliked Davidge at Christie’s—and there are many—talk of Samson pulling down the pillars of the temple. “He is the most appalling villain,” says one of his former colleagues. “He was always so full of hatred and envy.”

In this scenario, the Davidge file constituted the barrow boy’s final revenge on the senior partners who had sneered once too often at the printer and his blow-dried hair. Certainly Davidge had always gloried in his subversive streak. “In Kensal Rise,” he proudly told the Financial Times when he was 50 and the chief executive, “you can still see where I wrote ‘Ban the Bomb’ on the wall.”

So was there malice combined with sabotage in the butler’s parting gift? Christopher Davidge has nothing to say. The happy chappie is living comfortably with his federal amnesty, his handsome financial settlement, and Amrita Jhaveri.

Collusion and competition have marked Sotheby’s and Christie’s love-hate relationship for nearly 250 years, since they worked in wary alliance during the reign of George III, tickling the acquisitive palates of the new rich created by England’s Industrial Revolution. Sotheby’s auctioned books and manuscripts; James Christie sold paintings, jewelry, and fine objects.

They shared business openly. While Sotheby’s were cataloguing the library of a country house, Christie’s would be at work in the picture gallery valuing the portraits. Christie’s smuggled out the jewels of France’s ruined aristocrats during the French Revolution; Sotheby’s got Napoleon’s library—and his walking stick.

The sale of the walking stick was an early example of an art form both firms were to make peculiarly their own: the auctioning of intrinsically worthless objects as celebrity relics, the showy modem equivalent of saints’ bones. Sotheby’s shocked early-20th-century London by putting the personal possessions of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning on the block, but a deftly worded catalogue brought frenzied bidding for cuff links and dinner plates, along with the couple’s intimate and poetic love letters.

The moment that started the houses on their modem history came a few weeks after the Browning sale, when Sotheby’s unilaterally abandoned the no-compete gentleman’s agreement that had hitherto regulated their rivalry. On June 20, 1913, they offered for auction a major portrait by the Dutch artist Frans Hals on the same day that Christie’s were offering a couple of Frans Hals paintings in their own galleries. Sotheby’s, traditionally the book-and-manuscript auctioneers, got the better price.

The particularly poignant bitterness in the battle between Sotheby’s and Christie’s stems from the fact that they were once friends, and that even in their fiercest battles they have, until the events of recent months, taken their cues from each other. With their silk ties, mahogany auction boxes, and upper-crust Englishness, they have maintained an aura that pays surprising homage to their common roots. Yet while they see themselves as latter-day Montagues and Capulets, locked in heroic battle to the death, the outside world tends to look on them more cynically as partners in a process which, until now, has worked out very profitably for both of them.

At Sotheby’s it was a tall, complex Old Etonian, Peter Cecil Wilson, who set the pace in the 1950s. Blessed with immense charm and an extraordinary aesthetic sense, Wilson filled Sotheby’s with original young talents who devised flashy new ways of stealing business from Christie’s. They came to America, taking over the venerable Manhattan auction house of Parke-Bemet, and set themselves up proudly on Madison Avenue. For more than 40 years, they made Sotheby’s No. 1.

But the auction house faltered after Wilson’s retirement, opening the way for a takeover in 1983 by the then obscure figure of A. Alfred Taubman, an art-collecting midwesterner who had made his fortune building and operating shopping malls.

In the small, sleepless hours of the night, lAl Taubman had always worried that it might end in tears. A friend remembered the tycoon cutting short a cruise ahead of schedule because he felt uneasy away from the office. “I’ve got to go back,” he fretted, his eyes haunted with panic. “Who knows what could be happening there?”

A specter hovered over Taubman, the memory of his father, Philip, a developer in Pontiac, near Detroit, who had lost his business during the Depression. Philip Taubman had had to go out to work in the orchards of Michigan’s lake country as a sharecropper, leaving young A1 with the feeling that he could never work hard enough.

This insecurity may underlie the cheerful disbelief with which Taubman accepted the social eminence he acquired with Sotheby’s. Big A1 the mall builder had had difficulty attracting the full society roll call to his gatherings. But when A. Alfred Taubman, the new owner of Sotheby’s, threw a party in Palm Beach to celebrate his acquisition in 1983, attendance was 100 percent. “Look at this crowd,” he said with a grin, a sleek and happy shark suddenly surrounded by obsequious pilot fish. “How did I get invited?”

Though at his worst he could be arrogant and bombastic, Taubman had a disarming side, with the diffidence of the left-handed, dyslexic student from Pontiac High who could not hack spelling and as a result concentrated on drawing instead. “He had this gift for seeing three-dimensionally,” remembered his old friend and mentor Max Fisher. “He could pull out a piece of tissue paper and draw on it anything you wanted.”

In the 1960s, Taubman helped Fisher redesign his Speedway gas stations in Detroit, and later was his partner in the prodigiously profitable development of the Irvine Ranch in Southern California into commercial and residential real estate. The profits from the Irvine Ranch provided the cash that bought Sotheby’s in 1983.

Coherent design and customer flow were the secret of Taubman’s successful shopping malls, and he brought the same concepts to his auction house. The mall-meister worked wonders straightening out the rabbit warren of offices on New Bond Street, and he did the same for Sotheby’s York Avenue quarters in Manhattan. Toward the end of the 1990s, the two auction houses embarked on the rival construction of ambitious new headquarters, and it was thanks to Taubman that Sotheby’s won the battle hands down. Christie’s took over a Rockefeller Center parking garage to produce a somber set of rooms with all the character of a Four Seasons Hotel. Up on York Avenue, Taubman commissioned a veritable wedding cake of steel and wood and glass, where light streams in from every side, and the high-ceilinged galleries have a cathedral-like atmosphere.

“It suggests that someone has applied his mind to rethinking the business,” says a Taubman associate. “The drama of the building reflects the drama of the auction.”

The pity of it is that Taubman’s auction mall may prove to be his memorial. His lawyer Scott W. Muller insists that his client “has acted openly and aboveboard in all matters.” But as the art world and society ponder how the next shoe may fall for Sotheby’s, there is a definite chill, even a faint hint of contagion, developing around the name of Taubman. “People still entertain them, and of course the subject is never mentioned,” reports a Palm Beach socialite. “But behind their backs it’s the only thing we’re talking about.”

It was a sign of this social erosion when J-the New York Post’s “Page Six” followed the news of the Sotheby’s shake-up with a thinly veiled blind item on March 7 that dared to place a public question mark over the state of the Taubman marriage.

“You can lose your position overnight,” warns one of their friends. “She doesn’t realize yet. Her social access is going to dry up.”

The “she” in question is the controversial Judy Taubman, the former Israeli beauty queen whom Taubman met after the breakup of his first marriage. The second Mrs. Taubman had worked for a time on the front counter at Christie’s, where, as at Sotheby’s, the young ladies were selected to be as glossy and desirable as the goods they were promoting. The legendary perk of the front-desk finishing school was the chance to snap up a rich husband, and after the Taubman takeover Sotheby’s staff derived great satisfaction from the fact that their new chairman’s wife had made the legend come true. Rumors circulated that the former beauty queen kept a computerized inventory of the furs, gems, and other fabulous gifts Taubman showered on her, and when she posed in swimsuits for Town & Country, the saucy cover was pinned to bulletin boards in London and New York.

Senior experts at Sotheby’s speak warmly of Judy Taubman’s taste. She collects Chinese imperial monochromes, austere porcelain pieces made exclusively for the emperor, in a single color and of the finest quality. But auction houses are about the application of social status to art, and for Judy Taubman, her husband’s 17-year ownership of Sotheby’s has been a wonderful springboard to social summits that she would not otherwise have reached. “Judy is completely obsessed by minor royals and aristos,” says one auction-house insider. “Then A1 puts them on the board of Sotheby’s.”

Dede Brooks has made a few enemies of her own, but the news of her downfall has evoked more compassion. Even some Christie’s folk have dared express regret, always in a deeply off-the-record capacity. Never had a woman risen to such heights in the auction business.

The odd thing about the career of the hard-driving and self-willed Dede Brooks was that if she had been a man no one would have thought twice about it. Her gogetter style conformed to the stereotype of countless extroverted male executives, but she inspired great tenderness in those who liked her. “I know about Dede’s heart, and it is a good one,” says Hugh Hildesley, who was her colleague at Sotheby’s and also her pastor for a period as rector of Manhattan’s Church of the Heavenly Rest.

“We laughed a lot and had a lot of fun,” remembers Tobias Meyer, the sharp-witted contemporary-art expert Brooks recruited from Christie’s. “I enjoy her intelligence and speed. I liked her as a person.” Then he pauses guiltily at having spoken in the past tense and corrects “liked” to “like.”

The curious and dynamic mixture that is Diana Dwyer Brooks was formed on the North Shore of Long Island, where the Dwyer family belonged to the Piping Rock Club and appeared in the Social Register. Her father, Martin, liked to foster competition among his children. “Which of you has done the best today?” he would ask over dinner. “From the start,” remembers a friend, “Dede needed to show her father she could do as well as his boys.”

Jamie Niven, son of the actor David Niven and a vice-chairman at Sotheby’s, remembers dueling with Dede on the golf course and winning $12: “She just hated to lose. Next day she came in and laid the $ 12 on my desk. ‘I don’t think you’re working hard enough,’ she said through gritted teeth. It was not really a joke.”

A sports star at school—she graduated from Miss Porter’s, the alma mater of Jackie Kennedy—Dede went to Yale, as the men of her family' were supposed to, and then into banking. After marriage to venture capitalist Michael C. Brooks and the birth of two children, she entered Sotheby’s on the finance side, but achieved the rare feat for an expense checker of winning the affection of the experts.

“We’d spent years discussing the feasibility of setting up an outfit to do furniture restoration,” remembered Robert Woolley. “Then this new girl appeared [from the accounts department] and ran her finger down the figures. ‘That makes sense,’ she said. ‘Let’s do it.’”

“Attack, attack, attack!” was how her predecessor, Michael Ainslie, once characterized Brooks’s business style. At one Christmas party, Ainslie presented her with a pair of brass balls. “Try cracking these, Dede,” he said, “and stop cracking mine.”

“I didn’t know you had any, Michael,” Brooks retorted instantly to her boss.

Ainslie saw her aggressiveness as an asset and kept promoting her. It was owing to Brooks’s foresight and tight financial management that Sotheby’s laid off fewer staff members than Christie’s did during the dark days of the early-1990s art recession, and she was the hands-on C.E.O. when Sotheby’s came up with the revenue-enhancing reorganization of sales-commission rates in April 1995.

That act of revenue enhancement, the world has since discovered, was the stumbling point. No one is yet saying what Brooks did, or failed to do, in her dealings with Alfred Taubman and Christopher Davidge to find herself now facing the possibility of prosecution, fines, jail, and massive legal expenses. But what seems certain is that a phenomenally driven and compulsive career has been spectacularly derailed.

There is a strange echo of this tragedy in the recent history of Brooks’s own family. Throughout her childhood, Diana Dwyer was particularly competitive with her elder brother Andy, who took over the family business—a utility company serving Jamaica, Long Island—and became a wunderkind of the go-go 80s. Diversifying into high-tech office services and electronics, Andy Dwyer was the subject of admiring business articles as he rattled through the creation of a $3 billion conglomerate, which in 1991 took control of the computer-reselling chain Businessland.

If old Martin Dwyer had still been alive, he would surely have awarded Andy the family prize for achievement. But 17 months later the driving Dwyer strategy unraveled dramatically after reported complaints of improper and questionable accounting practices. In 1992, Andy Dwyer found himself facing shareholder suits in federal court.

In the end the suits were settled out of court. Dwyer’s mistakes turned out to have been matters of overambition in an economy that was slowing down. But a phenomenally driven and compulsive career had been spectacularly derailed.

Dede Brooks is not going easily. Leaks from the inquiry suggest that she too approached the Justice Department with an offer to cooperate in exchange for leniency, but was beaten to the door by Christie’s. “She missed out by a week,” according to a report in The New York Times.

With immunity, according to people involved in the case, Brooks was prepared to tell prosecutors that she had met with Davidge on orders from Taubman, and this alleged attempt by the C.E.O. to rat on the chairman was the crucial factor as the Sotheby’s board considered the need for Brooks and Taubman to step down.

“If she hadn’t done that,” says a Taubman intimate, “the board would have said, ‘We are going to stand by you both.’ As it was, they both had to resign.”

Brooks’s former boss did not appreciate her apparent willingness to shop him. “From that moment,” says a close observer, “there isn’t a relationship between them.”

Taubman’s dearest wish is to clear his name and again direct the destiny of the company he rescued in 1983, but it is difficult to see much future at the auction house for the woman who was once the face of Sotheby’s.

IT’S NOT EASY BEING QUEEN, ran the jaunty motto on one of the needlepoint pillows that decorated the space Brooks occupied on the eighth floor of the firm’s airy new headquarters. In March that pillow sat with its fellows in a laige bag, waiting to be taken away, and the eighth floor was strangely silent.

John J. Greene, a laconic, 54-year-old prosecutor from Brooklyn, oversees the New York field office of the Justice Department’s anti-trust division, and he seems to be extracting wry amusement from the mayhem that its investigations have wrought. For 14 years the field office has been dredging through the murky shallows of the art world with only moderate success. Now Christopher Davidge’s file of papers has hooked Greene a couple of really big fish.

“Are you the guy who’s betting on Dede?” he asks when I question the strength of the Justice Department’s case. His voice has the timbre of a man used to dealing with people who are very scared of him.

Greene’s inquiry started after an auction in April 1986, when a 19th-century American mahogany chest went on sale at Christie’s East, the low-budget, Manhattan equivalent of Christie’s South Kensington, London. Numbers etched on its side indicated that it had once been the property of the noted American collector Mabel Brady Garvan, but Christie’s failed to spot the full value, and a dealer got the item for just $30,800. Minutes later this dealer and his ring of dealer colleagues, who had conspired to keep the price down by not bidding against one another, held their own private auction in a parked car outside the 67th Street salesroom. They now competed genuinely, bidding the chest up to $38,000 in a bid-off process known as “ringing” or a “knockout,” and shared among themselves the $7,200 they had denied the auction house and the seller.

Greene’s anti-trust squad scored three guilty pleas and $170,000 in fines for that conspiracy and went on to convict seven more antiques dealers of auction rigging in New Hampshire and Rhode Island. A number of the dealers seriously maintained that they had not realized that their habit of “ringing” together to keep down auction prices was illegal—a signal to Greene of the laissez-faire practices of the art world.

Art was not the only concern of the New York anti-trust office. In the early 1990s, Greene investigated the kosher-foods industry and successfully prosecuted Manischewitz, the Jersey City baker, for the price-fixing of kosher-for-Passover matzo. Then, in 1997, he stunned the art world by subpoenaing the records of Christie’s and Sotheby’s, along with the papers of such major dealers as Acquavella and William Beadleston. “They wanted everything—including the office Rolodex,” remembers one of the dealers. “And after we’d carted it off to Federal Plaza, we discovered that the intern had only photocopied one side of the Rolodex cards.”

The cases of documents are still in the anti-trust division’s austere offices in Lower Manhattan, along with a growing collection of glossy auction-house catalogues. The assembled diaries and appointment books of the world’s busiest dealers make up a priceless record of networking at the art world’s most rarefied levels.

“I can’t afford to buy art,” Greene told The Wall Street Journal, though he confessed that he has taken to strolling through auction previews in the lush halls of both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, where no one has any idea who he is.

Considerably more high-profile is Greene’s boss in Washington, Assistant Attorney General Joel I. Klein, the man who took on Microsoft and won. His humbling of Bill Gates—he hired crack lawyer David Boies to cross-examine Gates and later present his department’s anti-trust case in court—has made Klein the most feared regulator of his generation. The Sherman Act brought down John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil in 1911, and Klein’s proclaimed goal is to apply its anti-trust provisions to modem businesses. His trophies include Hoffmann-LaRoche and B.A.S.F., fined $500 million and $225 million, respectively, in 1999 for fixing the price of vitamins, and a trio of Archer Daniels Midland executives sentenced in 1998 to a total of six and a half years in prison. The extraordinarily unregulated fine-art-and-auction business provides his department with a very obvious target. “In essence, this auction-house case isn’t much different from a bunch of good of boys down South who’ve got together to fix road contracts over a couple of whiskeys,” says a New York attorney who specializes in anti-trust law.

The prospect of jail sentences concentrates the mind wonderfully. Brooks and Taubman are currently engaged in the ritual propitiations that anti-trust suspects traditionally offer on the altar of the fearsome Sherman Act. Their resignations were just the first ploy.

“It’s very, very serious,” says someone close to the case. “We understand that a grand jury was formed as long as three years ago, and when a grand jury has been around that long, it is getting hungry and dangerous. It’s looking for indictments. Anti-trust prosecutors do not want to read defiance, or anything surprising, in the newspapers. They want to see some humility, respect for the process.”

Dede Brooks’s prompt listing of her Greenwich home could be a token of humility. But she and her husband have also acquired a new residence in Florida, and that, according to a South Florida attorney, could be a way of shielding assets under the state’s homesteading laws, which protect Florida property from many creditors and court judgments.

Taubman’s continuing ownership of Sotheby’s could be another subject for negotiation with the prosecutors of the anti-trust division, whose code insists that those whom they corner should not only suffer but also be seen to suffer. Given to gnomic and chilling pronouncements such as “The law is the law,” these Robespierres do not joke much, and when they do, it is with a grim gallows humor acquired from watching the rich and powerful squirm.

In fact, prosecutor John Greene is currently the most powerful figure in the art world, since the outcome of his inquiry could reach far beyond Taubman and Brooks. If Greene establishes proof of collusion between the auction houses, it will open the way for a flood of class-action suits to which Christie’s will be as vulnerable as Sotheby’s. As an old and valued client and customer of Christie’s, the Canadian collector Herbert Black was included among those phoned to get private notice of the Justice Department amnesty. Black listened politely, consulted his lawyer, and within days filed suit against both houses.

Anyone who has bought or sold anything at either Christie’s or Sotheby’s since the date of the alleged commission fixings could have a case. In the last few months, Internet sites have sprung up where you can sign on to sue the auction giants. And as a public company Sotheby’s is also liable to suits from shareholders, who may claim that they paid too much, or that their shareholding has lost value because of the alleged collusion. Anti-trust laws provide for damages up to treble the sum lost, so the cost of the class actions could run to tens of millions of dollars.

The two new C.E.O.’s appointed by the boards of Christie’s and Sotheby’s to take the places of Davidge and Brooks are a couple of tough, fresh-faced, and remarkably muscular men in their early 40s. To contemplate their sturdy, six-foot-something frames is to wonder if both were not picked for their confidence-inspiring bulk.

William Ruprecht (Sotheby’s) looks like a professional football player. Edward Dolman (Christie’s) actually was an amateur Rugby player until a year or so back. He played loose head prop, one of the stocky, cranium-bashing gladiators in the front row of the scrum, and since being named Christie’s chief executive last December, he has dealt rapidly and robustly with the problems that have landed on his plate.

“Ed Dolman is strong, honorable, decent, and very bright, too,” says one Christie’s insider. “He is everything Davidge was not.”

Bill Ruprecht is a vigorous auctioneer whose deep voice can energize a salesroom. Trained over beer and sandwiches by the legendary John Marion, Sotheby’s U.S. boss before the Taubman takeover, Ruprecht is an all-American figure who revives the traditions of the Parke-Bemet auction house, from which Marion came. Sotheby’s seems calmer already under his steady hand.

Both men have said in politely veiled criticism of their egotistical predecessors that they see themselves as team leaders— “ringmaster” is Ruprecht’s term—and many art-world insiders see that as a good thing.

“When Dede got to the top,” recalls one of her former colleagues, “she just crowded out her experts. She wanted to take the big auctions. She loved taking over the clients, and some very high-level experts left Sotheby’s because of that.”

This spring the two auction houses’ sets of experts have managed to corral a respectable but unspectacular array of paintings for their banner May and June sales by scurrying busily, and by almost certainly charging lower sales commissions than they would have liked. Their problem has been less the Justice Department investigations than the uncontrollable hazards of a mild winter. As one expert put it, “No dead collectors—no paintings to sell.”

The serious, long-term challenges to both houses lie at a level above Ruprecht and Dolman. In Christie’s case, the problems swirl around the firm’s enigmatic French proprietor, Francois Pinault, for just as the auction house seemed to have escaped the worst by cutting its deal with the Justice Department, The Economist published a devastating expose of Pinault’s secretive offshore tax arrangements. Suggesting that the fortune with which Pinault acquired Christie’s was built through risky, questionable, and possibly illegal business dealings, the magazine documented numerous incorrect and misleading filings made by Pinault in Europe and America. These are offenses under French and U.S. stock-market rules. It also detailed a case in which California insurance regulators are adding Pinault’s name to a lawsuit alleging fraud.

Pinault’s lawyers have “strenuously denied” the allegations—which the magazine repeated and amplified three weeks later. Ed Dolman says he has no comment to make on his boss’s personal business affairs. But if Christie’s profits are being channeled into Pinault’s allegedly tax-evading corporate structure, it seems inevitable that the Justice Department will come calling.

Alfred Taubman has so far enjoyed a charmed life with litigation. In a memorable case in the 1980s, he sued the architect Richard Meier for the leaky roof of his Palm Beach home, escorting the judge and jury on a tour of his damp spots after having cleared the house entirely of his furniture, art, and possessions for the day. For a whole morning in court, Meier’s attorney tried to discredit Taubman in the eyes of the jury by running through the details of the tycoon’s shopping malls, private Gulfstream jet, cook, servants, and generally extravagant lifestyle, concluding with the question “Are you, in fact, a very wealthy man?”

“Yes,” replied Taubman, “I am a wealthy man—with a leaky roof!”

The jury laughed, and the case was won. Taubman was awarded more than $700,000 to repair his house. And it may just be that he had a trick up his sleeve in his current dilemma, for appointed to succeed him as chairman of Sotheby’s is the much-admired academic Michael I. Sovern, the former president of Columbia University. An engaging and humorous character, Sovern has a reputation for successful conflict resolution, starting with the Columbia riots in 1968, and Sotheby’s has proudly listed his many appointments: member of the board of directors, N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund; consultant on law to Time magazine; consultant to the Ford Foundation; member of the Pulitzer Prize board; and many more.

The list does not, however, include the appointment which might seem to be the most useful of all in Sotheby’s current situation. From 1994 to 1997, Sovern served as a founding trustee of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s Presidential Legal Expense Trust, which raised more than $1.3 million toward the costs of defending the president and his wife from charges arising over their involvement in the Whitewater scandal.

“I did believe, and still believe,” says Sovern, “that his legal expenses were a function of his role as a political leader. A president should not be punished by being driven into bankruptcy.”

Handling Whitewater matters for the Clintons was Deputy White House Counsel Joel I. Klein, who took over the job following the mysterious suicide of Vince Foster in 1993. Klein worked directly for Clinton until 1995, when he moved on to the Justice Department’s anti-trust division.

Sovern put his reputation on the line to help fund the lawyers working under Klein’s instructions, and the ultimate beneficiary of his gesture has been President Clinton himself. “This is money he will remember,” says campaign-finance reformer Charles Lewis, talking of Clinton’s likely attitude toward those who have helped him with his legal expenses. “This is blood money.”

“I wish!” is Sovem’s laughing response to the idea that his Clinton connection could get Sotheby’s off the hook. “The president isn’t going to get involved,” he says, “and Joel Klein is a man of integrity. It’s out of the question.”

Insiders concur. “Clinton isn’t particularly close to Taubman,” says someone who knows the president well. “The president can’t afford another scandal, and he isn’t particularly close to Janet Reno or Joel Klein for that matter.”

Riding high as the man who dragged Microsoft across the gravel, Joel Klein has little motive for muddying his record with an auction-house compromise—unless his department lacks the evidence to convincingly nail Taubman and Brooks, and as the inquiry drags on, this is looming as a possibility. Lawyers acting for Sir Anthony Tennant, the former Christie’s chairman who is said to have been implicated by Davidge in conspiratorial meetings and communications, have insisted on their client’s innocence. Thus Tennant, a Christie’s man, has effectively joined Taubman in contradicting Davidge’s evidence. This may leave the Justice Department with Davidge as its only witness, which could lead to defense attorneys’ raising serious questions of character and motivation if the case ever got to court. Davidge’s papers alone may not be sufficient to send Taubman and Brooks to prison.

More regulation for the auction houses? That seems certain—along with new rules to cover the dealers. After 14 years of investigation, the final package must look credible. This crisis strikes a business that is already under threat. With international sales of nearly $3 billion in 1999, eBay, the Internet auctioneer, is already doing more business than either Christie’s or Sotheby’s, and it is ironic that the two old houses face collusion charges at a moment when they have adopted radically different responses to the challenge. Christie’s has an attractive Web site, but compared to Sotheby’s, which has recently invested more than $40 million in its complex of Internet trading services, it has barely dipped its toe in the electronic waters.

The future suggests a spectacular transformation and expansion of the art market that could pass either or both of the houses by. An April S.E.C. filing by Baron Capital, the largest outside shareholder in Sotheby’s, signaled discontent with the “composition and independence” of the firm’s board of directors (Taubman intended to have his son Robert replace him on the board). That could herald takeover activity. Rumored suitors include eBay, as well as Sotheby’s Internet partner, Amazon.com, and, most piquantly of all, Bernard Arnault, the French luxury-goods tycoon, who is a bitter rival of Christie’s owner, Francois Pinault. The two men tussled last year over Gucci. Pinault won. But Arnault, the boss of L.V.M.H. Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, already owns and is investing heavily to build Phillips, the world’s No. 3 auction house, into a major player; in February he added Etude Tajan, Paris’s top auction firm, to his empire.

“Arnault’s really putting money on the table,” says an auction insider in London. “He’s pouring money into Phillips to get them the properties.”

So will Bernard Arnault swallow up Sotheby’s, consigning the old British houses into the hands of two Frenchmen with their own Gallic rivalry? The ancient duopoly seems destined for change. But fears of Armageddon are probably exaggerated. In fact, there’s an old art-world saying: When Armageddon is over, Sotheby’s and Christie’s will still be around to auction off the ashes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now