Abstract

Free full text

Factors Associated with Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Kinetics and Responses in Pegylated Interferon Alpha-2a Monotherapy for Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B

Abstract

Objective

Pegylated-interferon monotherapy is the standard treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis B; however, the factors associated with its therapeutic effects remain unclear.

Methods

Patients with chronic hepatitis B were treated with pegylated interferon α-2a for 48 weeks. We evaluated the kinetics of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) during treatment and follow-up periods and the factors associated with an HBsAg response (defined as a change in HBsAg of ≥-1 log IU/mL from baseline).

Results

The study population comprised 50 patients. The median baseline levels of hepatitis B virus DNA and HBsAg were 5.00 and 3.40 log IU/mL. The median values of HBsAg reduction from baseline were -0.44 (n=48), -0.41 (n=40), and -0.68 (n=11) log IU/mL at the end of treatment and at 48 and 144 weeks post-treatment, respectively. The rates of HBsAg response were 24.0% and 22.5% at the end of treatment and at 48 weeks post-treatment, respectively. A multivariate analysis identified HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL as an independent baseline factor contributing to the HBsAg response at the end of treatment and 48 weeks post-treatment (p=1.07×10-2 and 4.42×10-2, respectively). There were significant differences in the reduction of the HBsAg levels at 12 weeks of treatment and in the incidence of serum ALT increase during treatment between patients with and without an HBsAg response.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the baseline HBsAg level, HBsAg kinetics at 12 weeks of treatment, and ALT increase during treatment are important factors contributing to the HBsAg response in pegylated interferon α-2a monotherapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Introduction

The number of patients with persistent hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is estimated to be approximately 250 million, accounting for 3.5% of the global population (1). Chronic HBV infection increases the risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2, 3). Specifically, the level of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is an important factor associated with HBV-related carcinogenesis, as well as the HBV DNA level. The incidence of HCC is reduced in patients with diminished levels of HBsAg (4) and increased in those with an HBsAg level of >3.00 log IU/mL even if the HBV DNA level is low (5). Accordingly, the ultimate goal of treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis B is to achieve HBsAg clearance (6). However, at present, there is no effective treatment specific for HBsAg reduction or clearance. Furthermore, the annual rate of spontaneous disappearance of HBsAg is approximately 1%; thus, a long time is required to achieve the disappearance of HBsAg (7).

Nowadays, two antiviral agents - nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) and interferon (IFN) - are widely available for patients with chronic hepatitis B. NA inhibits the activity of HBV polymerase (e.g., entecavir and tenofovir) and has a potent inhibitory action against HBV replication and a high genetic barrier to the development of resistance (8, 9). However, even if NA is administered for a long time, HBsAg decreases or disappears in very few patients because NA has no impact on the denaturation or elimination of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) (10, 11). IFN, by contrast, inhibits not only viral multiplication but also immunostimulation activity against hosts, so the elimination of HBV-infected cells, denaturation of cccDNA, and consequent reduction of HBsAg production are expected in comparison with NA (12, 13). In addition, unlike long-term NA treatment, the IFN treatment period is short, and the therapeutic effect persists even under a drug-free condition after the completion of IFN administration (14).

There are two types of IFN preparations: conventional IFN and pegylated IFN (Peg-IFN). Conventional IFN alpha (IFNα) is unstable in the circulation, and its half-life is short; therefore, it has the burden of frequent administration and adverse effects on the patients (15). Peg-IFNα-2a is prepared by covalently bonding 40-kD molecular-chain polyethylene glycol to IFNα-2a, therefore showing stable pharmacokinetics and an extended half-life in the circulation, leading to enhanced antiviral efficacy with less frequent administration, lower frequency, and less severity of adverse events and consequently favorable outcomes (16).

In several studies from East Asia (Japan and China), it has been reported that some baseline factors, such as age, severity of liver fibrosis, and HBV genotype, influence the effects of conventional IFN and Peg-IFN, including the normalization of the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) clearance, and loss of HBV DNA levels (17-19). However, these studies did not investigate which factors are associated with the reduction in the HBsAg level (20, 21). In contrast, in several studies from the West, it was reported that the on-treatment factor of HBsAg reduction during Peg-IFN monotherapy was able to predict HBsAg clearance after treatment (22-24), suggesting that the baseline factors contributing to HBsAg reduction during treatment may influence HBsAg clearance. Thus far, few studies have reported the baseline factors associated with HBsAg reduction in Peg-IFN monotherapy for Japanese chronic hepatitis B patients.

In the present study, we focused on the reduction in the HBsAg levels and HBsAg kinetics during treatment and investigated which factors contributed to the HBsAg reduction under Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy for Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study was a multicenter, retrospective study that included patients with chronic hepatitis B who were treated with Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy between October 2011 and March 2017 at the following hospitals: Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital, Nippon Medical School Hospital, Ootakanomori Hospital, Ogaki Municipal Hospital, Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital, and Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital. All patients who consented to participate in the study met the following criteria: 1) HBsAg persistently seropositive and HBsAb seronegative for ≥6 months prior to treatment; 2) no history of anti-HBV treatment; 3) grade 0 or 1 patient status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status criteria; 4) serum ALT level ≥31 IU/L and serum HBV DNA level ≥3.30 log IU/mL within 6 months prior to treatment; and 5) age ≥18 years old. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) presence of cirrhosis or liver failure; 2) presence of malignant tumors; 3) coinfection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus; 4) presence of other chronic liver diseases, such as autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis; 5) ongoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressor/immunomodulator treatment for any diseases; 6) laboratory data including a neutrophil count <1,500 /μL, a platelet count <75×103/μL, hemoglobin level <8.5 g/dL, serum albumin level <3.5 g/dL, and total bilirubin level >2.0 mg/dL; 7) thyroid dysfunction; 8) poorly controlled diabetes or hypertension; 9) history of interstitial pneumonia; 10) depression; or 11) hypersensitivity to Peg-IFN.

This study was designed according to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before their participation.

Treatment protocol

Peg-IFNα-2a (PEGASYS; Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at a dose of 90 μg for the initial 4 weeks and 180 μg for the subsequent 44 weeks was administered weekly to all patients. Discontinuation and dose reduction in the Peg-IFN were determined according to the dosing criteria to avoid severe adverse events (grade ≥3).

Laboratory tests and HBV-related markers

Physical, hematological, and biochemical examinations were performed every two weeks for the first eight weeks and every four weeks during the remaining treatment period and the follow-up period. When other treatments, such as NA, were introduced during the follow-up period, the time of initiation of other treatments was considered as the censored time. The levels of serum HBeAg and antibody to HBeAg (HBeAb) were measured using the ARCHITECT HBeAg and HBeAb assay kits (Abbott Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). HBV genotypes were determined with a commercial kit, using a combination of epitopes expressed on the pre-S2 region product (HBV Genotype EIA; Institute of Immunology, Tokyo, Japan). Serum HBV DNA levels were quantified using Cobas TaqMan HBV v.2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan). Serum HBsAg levels were quantified using the ARCHITECT HBsAg QT assay kit (Abbott Laboratories). Serum HBV core-related antigen (HBcrAg) levels were quantified using a fully automated analyzer system (Lumipulse System; Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan).

HBsAg kinetics and treatment endpoints

Serum HBsAg levels were examined every four weeks during treatment and every three months post-treatment. Time-course changes in the HBsAg level from baseline were analyzed during the treatment and post-treatment periods. The primary endpoint was an HBsAg change of ≥-1 log IU/mL from baseline. The secondary endpoint was serum HBV DNA decline to <3.30 log IU/mL and serum ALT normalization (<30 IU/L).

Definition of treatment responses

HBsAg-response, virological response, and biochemical response to Peg-IFN monotherapy were defined as an HBsAg change of ≥-1 log IU/mL from baseline (25, 26), an HBV DNA level <3.3 log IU/mL, and an ALT level <30 IU/L, respectively. Patients were assessed for HBsAg response, virological response, and biochemical response at the end of treatment and at 48 weeks post-treatment. Time-course changes in the serum HBsAg level from baseline (“HBsAg kinetics”) were compared between two groups into which the patients were divided for each baseline variable.

According to a previous study (21), an ALT increase during the Peg-IFNα-2a administration period was defined as an elevated serum ALT level to ≥100 IU/L or twice the baseline level and a serum ALT level ≥50 IU/L. During the post-treatment period, patients with a serum ALT level ≥80 IU/L or serum HBV DNA level ≥5.00 log IU/mL were regarded as experiencing relapse of hepatitis, and physicians considered this an indication for NA treatment in those patients (27).

Fibrosis markers

In order to evaluate liver fibrosis, the FIB-4 index was calculated as a fibrosis marker. An FIB-4 index value <1.45 was defined as the absence of advanced liver fibrosis (28).

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as medians and ranges, and categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The HBsAg kinetics was examined using Wilcoxon's signed-rank test. The optimal cut-off value for the HBsAg reduction levels during treatment for HBsAg response was calculated using a receiver operating characteristic curve. A logistic regression analysis for univariate comparisons was performed to investigate whether each factor was associated with HBsAg response. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify significant, independent baseline factors that contributed to the HBsAg response. All statistical analyses were performed using the Excel Statistics 2015 software program (SSRI, Tokyo, Japan). The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 50 patients with chronic hepatitis B were subjected to the current analysis (Table 1). The patients were 28 (56.0%) men and 22 (44.0%) women with a median age of 45 years old (range, 22-70 years old). There were 16 HBeAg-positive patients (32.0%) and 34 HBeAg-negative patients (68.0%). HBV genotypes A, B, and C were detected in 7 (14.0%), 12 (24.0%), and 30 (60.0%) patients, respectively. The median HBV DNA and HBsAg levels were 5.00 log IU/mL (range, 3.30->9.10 log IU/mL) and 3.40 log IU/mL (range, 1.08-5.10 Iog IU/mL), respectively. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 50 Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Who Were Treated with Peg-IFNα-2a Monotherapy.

| Factors | All patients (n=50) |

|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 45 (22-70) |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 28/22 |

| HBeAg-positive/HBeAg-negative | 16/34 |

| HBV DNA (log IU/mL)a | 5.00 (3.30->9.10) |

| HBsAg (log IU/mL)a | 3.40 (1.08-5.10) |

| HBcrAg (log IU/mL)a | 3.00 (<2.90-7.00<) |

| HBV genotype (A/B/C/missing) | 7/12/30/1 |

| White blood cell count (/μL)a | 5,170 (2,940-10,800) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)a | 14.4 (9.2-16.5) |

| Platelet count (×103/mm3)a | 20.0 (10.5-38.0) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)a | 37 (12-312) |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 27 (17-279) |

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL)a | 2.9 (1.1-106.2) |

| FIB-4 Indexa | 1.57 (0.41-12.38) |

Categorical variables are given as number. a Continuous variables are given as median (range).

Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, HBcrAg: hepatitis B virus core-related antigen

Two patients discontinued Peg-IFN treatment at 24 and 41 weeks of treatment due to adverse events (depression and general fatigue), respectively, while the remaining 48 patients completed the 48-week treatment course as scheduled. Thirteen patients received NA treatment during the follow-up period. The median period from the end of Peg-IFN treatment to the start of NA administration was 9 months (range, 3-29 months). The time of the initiation of NA treatment was considered as the censored time, and the median follow-up period of all patients was 27 months (range, 3-72 months).

Treatment efficacy

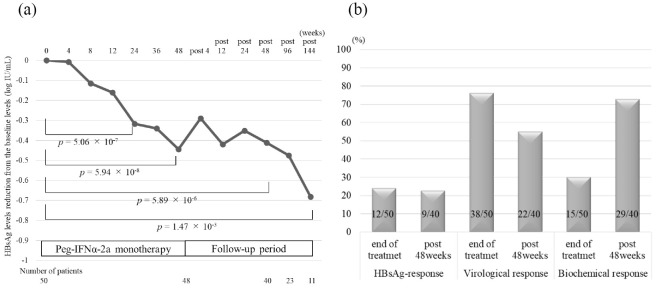

The median HBsAg changes from baseline were -0.32 and -0.44 log IU/mL at 24 and 48 weeks of treatment, respectively (p=5.06×10-7 and 5.94×10-8, respectively, compared to baseline; Fig. 1a). During the follow-up period, these changes were -0.41 and -0.68 log IU/mL at 48 and 144 weeks post-treatment, respectively (p=5.89×10-6 and 1.47×10-3, respectively, compared to baseline; Fig. 1a). The HBsAg levels thus continued to decline during the treatment period, and the reduced HBsAg levels were maintained and decreased further even after treatment had ended (Fig. 1a). Regarding the analysis including the patients who received NA treatment during the follow-up period, the median HBsAg changes from baseline are shown in Supplementary material 1a.

Treatment responses in patients treated with Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy. (a) HBsAg kinetics during the treatment and post-treatment periods; HBsAg levels gradually decreased during the treatment and follow-up periods. (b) Treatment responses (HBsAg response, virological response, and biochemical response) at the end of treatment and 48 weeks post-treatment. Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

The rates of HBsAg response were 24.0% (12/50) and 22.5% (9/40) at the end of treatment and at 48 weeks post-treatment, respectively (Fig. 1b). The rates of virological response were 76.0% (38/50) and 55.0% (22/40), respectively (Fig. 1b). The rates of biochemical response were 30.0% (15/50) and 72.5% (29/40), respectively (Fig. 1b). Regarding the analysis including the patients with NA administration considered to have no response to Peg-IFN treatment, the rates of HBsAg response, virological response, and biochemical response are shown in Supplementary material 1b.

In the 16 HBeAg-positive patients, the rates of HBeAg seroconversion were 12.5% (2/16) and 25.0% (4/16), respectively. HBsAg clearance was noted in 2 patients at 112 weeks and in 1 patient at 160 weeks post-treatment. The 3 patients who achieved HBsAg clearance were all HBeAg-negative and had HBV genotype C. The HBsAg levels at baseline in the patients who achieved HBsAg clearance were all less than 3.00 log IU/mL (1.08, 2.27, and 2.96 log IU/mL; Supplementary material 2).

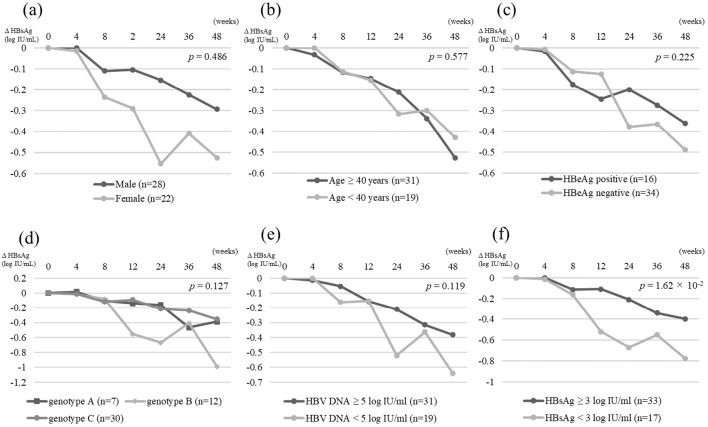

HBsAg kinetics according to baseline factors

Patients were divided into two groups by each category or cut-off value, and the HBsAg changes from baseline at the end of treatment were compared between the two groups. Regarding the gender, age, presence of HBeAg, HBV genotype, HBcrAg level, and FIB-4 index, there were no significant differences in the HBsAg attenuation kinetics between the two groups (Fig. 2a-d). Regarding the baseline HBV DNA levels, the decrease in the HBsAg level from baseline was greater in the patients with a baseline HBV DNA level <5.00 log IU/mL than in those with a baseline HBV DNA level ≥5.00 log IU/mL, although the difference was not statistically significant (-0.64 vs. -0.38 log IU/mL, p=0.119; Fig. 2e). Regarding the baseline HBsAg level, the decline in the HBsAg level from baseline was greater in patients with a baseline HBsAg level <3.00 log IU/mL than in those with a baseline HBsAg level ≥3.00 log IU/mL (-0.78 vs. -0.40 log IU/mL, p=1.62×10-2; Fig. 2f).

Baseline factors contributing to HBsAg-response

A univariate analysis identified HBV genotype B, HBV DNA <5.00 log IU/mL, HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL, and ALT <31 IU/L as baseline factors contributing to the HBsAg response at the end of treatment. In the multivariate analysis, HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL [p=1.07×10-2; odds ratio (OR), 6.50; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.54-27.39] was an independent factor contributing to the HBsAg response at the end of treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multiple Logistic Regression Analyses of Factors Contributing to HBsAg-response at the End of Peg-IFNα-2a Monotherapy.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Gender (Female) | 2.15 | 0.57-8.03 | 0.256 | ||||

| Age (≥40 years) | 4.05 | 0.78-21.02 | 0.096 | ||||

| HBeAg-negative | 2.50 | 0.47-13.27 | 0.281 | ||||

| HBV genotype (genotype B) | 5.33 | 1.28-22.25 | 2.16×10-2 | ||||

| HBV DNA (<5.00 log IU/mL) | 5.70 | 1.33-25.05 | 1.93×10-2 | ||||

| HBsAg (<3.00 log IU/mL) | 7.00 | 1.67-29.38 | 7.85×10-3 | 6.50 | 1.54-27.39 | 1.07×10-2 | |

| HBcrAg (<3.10 log IU/mL) | 2.00 | 0.52-7.66 | 0.312 | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase (<31 IU/L) | 4.35 | 1.09-16.66 | 3.75×10-2 | ||||

| Platelet count (<18.5×103/mm3) | 1.27 | 0.34-4.74 | 0.725 | ||||

| FIB-4 Index (<1.45) | 1.83 | 0.47-7.10 | 0.382 | ||||

Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, HBcrAg: hepatitis B virus core-related antigen, OR: odds ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidential interval

In the analysis of 40 patients not treated with NA within 48 weeks after the completion of treatment, univariate and multivariate analyses identified HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL (p=4.42×10-2; OR, 4.90; 95% CI, 1.04-23.04) as an independent baseline factor contributing to the HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multiple Logistic Regression Analyses of Factors Contributing to HBsAg-response at 48 Weeks after the End of Peg-IFNα-2a Monotherapy.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Gender (Female) | 1.52 | 0.34-6.75 | 0.583 | ||||

| Age (≥40 years) | 1.67 | 0.29-9.52 | 0.565 | ||||

| HBeAg-negative | 1.19 | 0.19-7.24 | 0.850 | ||||

| HBV genotype (genotype B) | 1.22 | 0.24-5.98 | 0.804 | ||||

| HBV DNA (<5.00 log IU/mL) | 2.42 | 0.51-11.51 | 0.263 | ||||

| HBsAg (<3.00 log IU/mL) | 7.35 | 1.28-41.98 | 2.49×10-2 | 4.90 | 1.04-23.04 | 4.42×10-2 | |

| HBcrAg (<3.10 log IU/mL) | 1.25 | 0.26-5.82 | 0.776 | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase (<31 IU/L) | 1.51 | 0.34-6.75 | 0.583 | ||||

| Platelet count (<18.5×103/mm3) | 3.95 | 0.87-17.99 | 0.076 | ||||

| FIB-4 Index (<1.45) | 1.06 | 0.26-4.37 | 0.933 | ||||

Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, HBcrAg: hepatitis B virus core-related antigen, OR: odds ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidential interval

Next, baseline factors contributed to HBsAg response were investigated according to HBeAg positivity. In the HBeAg-positive patients, a logistic regression analysis could not be performed due to the small sample size. Univariate and multivariate analyses identified HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL (p=2.47×10-2; OR, 7.93; 95% CI, 1.56-86.53) as a significant, independent baseline factor contributing to the HBsAg-response at 48 weeks post-treatment in HBeAg-negative patients.

HBsAg kinetics and ALT increase during Peg-IFN treatment

The HBsAg kinetics during treatment were compared between patients with and without an HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment. As shown in Fig. 3, the HBsAg levels continued to decline in HBsAg responders, whereas they were slightly reduced in HBsAg non-responders. Significant differences between the two groups were noted at 12 weeks of treatment, increasing with time (-0.65 vs. -0.09 log IU/mL at 12 weeks, p=6.01×10-3, Fig. 3). The optimal cut-off value of the HBsAg reduction from baseline at 12 weeks for predicting the HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment was -0.30 log IU/mL. Similarly, in the analysis including the patients with NA administration considered to have no HBsAg response, significant differences were shown at 12 weeks of treatment between HBsAg responders (n=9) and HBsAg non-responders (n=41) (-0.58 vs. -0.12 log IU/mL at 12 weeks, p=4.29×10-2, Supplementary material 3).

The comparison of HBsAg kinetics during Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy between HBsAg responders and non-responders. Significant differences between HBsAg responders and non-responders were noted at 12 weeks of treatment and increased with time. Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

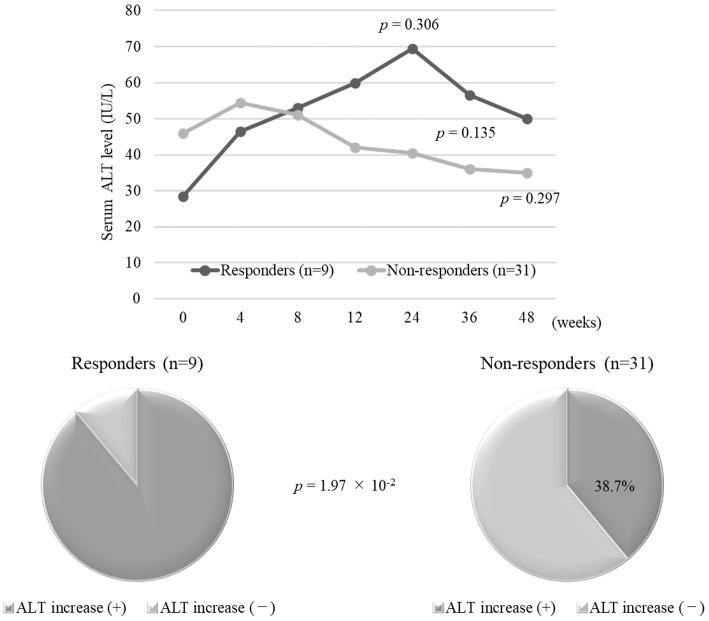

During the treatment period, the serum ALT levels were higher in HBsAg responders than in non-responders and showed a peak at 24 weeks, although the differences were not statistically significant (70 vs. 41 IU/L at 24 weeks, p=0.306, Fig. 4). The proportion showing an ALT increase during treatment was significantly higher among HBsAg responders than among non-responders [88.9% (8/9) vs. 38.7% (12/31), p=1.97×10-2; Fig. 4]. In the analysis including the patients with NA administration considered to have no HBsAg response, the results were similar (Supplementary material 4).

A comparison of the time-course changes in serum ALT levels and the prevalence of ALT increase during Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy between HBsAg responders and non-responders. Serum ALT levels in HBsAg responders were more elevated than those in HBsAg non-responder. The proportion of ALT increase during treatment for HBsAg responders was significantly higher than that in HBsAg non-responders. ALT: alanine aminotransferase, Peg-IFNα-2a: pegylated interferon α-2a, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

Next, among the patients with an ALT increase during treatment, the baseline factors were compared between HBs responders and HBsAg non-responders. The baseline HBsAg and HBV DNA levels in HBsAg responders were numerically lower than those in HBsAg non-responders (2.26 vs. 3.11 and 3.40 vs. 4.90 log IU/mL, respectively), although not to a statistically significant degree (p=0.113 and p=0.267, respectively).

Baseline characteristics of patients who required NA administration

Among the 13 patients who received NA treatment because of relapse of hepatitis during the follow-up period, 11 were treated with entecavir, and 2 were treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. The baseline factors were compared between the patients who did and did not require NA administration. Patients receiving NA were younger than those not receiving NA (35 vs. 49 years old, p=1.01×10-3). The HBeAg-positive rate was significantly higher in patients receiving NA than in those not receiving NA [76.9% (10/13) vs. 48.6% (18/37), p=7.08×10-6]. The serum baseline levels of HBV DNA (9.00 vs. 5.00 log IU/mL, p=6.26×10-4), HBsAg (4.38 vs. 3.15 log IU/mL, p=1.13×10-4), HBcrAg (6.80 vs. 2.90 log IU/mL, p=7.91×10-6), and ALT (72 vs. 33 IU/L, p=6.07×10-3) in patients receiving NA were significantly higher than those in patients not receiving NA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Patient Characteristics between Patients Who Needed NA Administration and Those Who Did Not Need NA Administration during the Follow-up Period.

| Factors | Patients who needed NA administration (n=13) | Patients who did not need NA administration (n=37) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 35 (26-58) | 49 (22-70) | 1.01×10-3 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 10/3 | 18/19 | 7.08×10-6 |

| HBeAg-positive/HBeAg-negative | 10/3 | 18/19 | 7.08×10-6 |

| HBV DNA (log IU/mL)a | 9.00 (3.70->9.10) | 5.00 (3.30-9.0) | 6.26×10-4 |

| HBsAg (log IU/mL)a | 4.38 (2.10-5.10) | 3.15 (1.08-4.58) | 1.13×10-4 |

| HBcrAg (log IU/mL)a | 6.80 (3.50-7.00<) | 2.90 (<2.90-7.00<) | 7.91×10-6 |

| HBV genotype (A/B/C/missing) | 2/0/10/1 | 5/12/20/0 | 0.095 |

| Platelet count (×103/mm3)a | 19.6 (10.5-36.7) | 20.0 (11.0-38.0) | 0.652 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)a | 72 (12-312) | 33 (13-228) | 6.07×10-3 |

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL)a | 5.2 (1.8-106.2) | 2.9 (1.0-49.7) | 0.075 |

Categorical variables are given as number. a Continuous variables are given as median (range).

NA: nucleos (t) ide analogue, HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, HBcrAg: hepatitis B virus core-related antigen

Discussion

The present study focused on the effect of 48-week Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy on the HBsAg kinetics and the baseline and on-treatment factors associated with the HBsAg response in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B. The results were as follows: 1) the HBsAg levels persistently declined during treatment, and the favorable response continued even after treatment completion; 2) HBsAg <3.00 log IU/mL at baseline was the only significant, independent factor associated with the HBsAg response; 3) elevated ALT values and an ALT increase during treatment occurred more frequently in HBsAg responders than in non-responders; and 4) a significant reduction in the HBsAg levels was observed as early as at 12 weeks of treatment in HBsAg responders.

Recently, it was suggested that the HBsAg kinetics are an important surrogate marker for evaluating anti-HBV treatment effects (4-6). Peg-IFN has been shown to be able to reduce the amount of circulating HBsAg and clear HBsAg from the serum, whereas NA has little or no such actions despite potently inhibiting HBV replication (10-13). However, unlike NA, Peg-IFN frequently causes adverse events with potentially high severity, causing intolerability and limiting its use and treatment period (29). Therefore, the identification of factors associated with a favorable treatment response will narrow down the number of suitable patients and improve the treatment outcomes.

Thus far, several factors have been reported to be associated with the effect of conventional IFN, whereas no influential factors have been reported yet for the outcome of Peg-IFN (17-20). In the natural course of chronic HBV infection, the HBsAg attenuation rate is accelerated with the reduction in the HBsAg level (7). Similarly, in Peg-IFN monotherapy, HBsAg clearance tends to occur with reduced HBsAg levels (22-24). Therefore, the determination of factors contributing to HBsAg reduction in Peg-IFN treatment may help identify patients who are likely to achieve HBsAg clearance.

The present study demonstrated that a low baseline HBsAg level (<3.00 log IU/mL) significantly and independently contributed to the HBsAg response at the end of Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy and at 48 weeks post-treatment. However, other studies have failed to show that the baseline HBsAg level predicts the treatment outcomes (30, 31). Physicians should note the following points when interpreting the results of this study: patients with a low baseline HBsAg level include not only chronic hepatitis B patients but also inactive carriers for whom antiviral therapy is not indicated as well as cases with advanced liver fibrosis where Peg-IFN therapy is contraindicated. Therefore, the indication for Peg-IFN monotherapy should be carefully decided by a hepatologist. However, some studies have reported that reduced HBsAg levels during treatment can predict the outcomes of Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy (22-24, 30, 31). In the present study, we compared the on-treatment HBsAg kinetics between patients with and without an HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment; the HBsAg levels continued to decline in HBsAg responders but were slightly reduced in HBsAg non-responders. Notably, a significant reduction in the HBsAg levels was noted as early as at 12 weeks of treatment in HBsAg responders, and the significant differences between HBsAg responders and non-responders increased with time. The optimal cut-off value for the HBsAg decline levels from baseline to 12 weeks for predicting HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment was -0.30 log IU/mL.

For Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy, a favorable therapeutic effect for HBV genotype A has been reported (20), whereas the present study identified genotype B as a baseline factor contributing to the HBsAg response at the end of treatment in a univariate analysis but not in a multivariate analysis. There were differences in the age, proportion of HBeAg-positive patients and baseline HBsAg levels between patients with genotypes B and non-B (Supplementary material 5). The differences in the baseline characteristics of patients among genotypes might affect the result of this study.

An ALT increase was reported to contribute to favorable outcomes in the natural course and with conventional IFN treatment (7, 32). In the natural course, it promoted a rapid decline and greater annual reductions of serum HBsAg levels in patients who achieved HBsAg clearance (7). With conventional IFN treatment, however, it was predictive of a virological response in patients with high serum HBV DNA levels (32). Regarding Peg-IFN therapy, an elevated serum ALT level was reportedly associated with the treatment response (21, 33, 34). In addition, an ALT increase occurred more frequently in responders than in non-responders, resulting in a pronounced decline in the HBsAg levels, and HBsAg clearance was achieved only in patients experiencing an ALT increase (33, 34). In the present study, elevated ALT levels during treatment occurred more frequently in patients who achieved an HBsAg response than in those without a response. These findings might be attributable to the host immune response induced by the immunomodulatory activity of Peg-IFN. HBV-infected hepatocytes might therefore be destroyed, resulting in a reduction in the intrahepatic cccDNA and serum HBsAg levels.

In the present study, 13 patients began to receive NA during the follow-up period due to relapse of hepatitis. We assessed the baseline factors of patients who did and did not require NA administration (Table 4). As a result, patients receiving NA was younger and had a higher HBeAg-positive rate and higher serum levels of HBV DNA, HBsAg, and HBcrAg compared to those not receiving NA. Therefore, younger patients who are HBeAg-positive and have high serum HBV DNA, HBsAg, and HBcrAg levels might require NA therapy, including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and tenofovir alafenamide, which was recently reported to have an HBsAg-reducing action (35), after the cessation of Peg-IFN treatment. These findings suggest that 48-week Peg-IFN monotherapy may be insufficient; therefore, additive NA administration or extended Peg-IFN treatment may be needed for such patients who are likely to have higher viral multiplication potency. In addition, retreatment with Peg-IFN monotherapy might also be an important strategy for sequential therapy in cases with elevated ALT levels.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, the number of patients analyzed in the study, especially the HBeAg-positive ones, was small. Second, the follow-up duration was short, so a further study will need to be conducted to clarify the long-term effectiveness of 48-week Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that the baseline HBsAg level, ALT increase during treatment, and the on-treatment HBsAg kinetics are important factors contributing to the HBsAg response in Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy for Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B. Specifically, monitoring the HBsAg kinetics during the first 12 weeks of treatment may be useful for predicting the HBsAg response.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Norio Itokawa, Masanori Atsukawa and Akihito Tsubota contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of baseline characteristics in patients with chronic hepatitis B who were treated with Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy according to HBV genotype.

There were differences in the age, proportion of HBeAg-positive patients and baseline HBsAg levels between patients with genotypes B and non-B

Treatment responses to Peg-IFNα-2a monotherapy in all patients, including those treated with NA during the follow-up period.

(a) HBsAg kinetics during the treatment and post-treatment periods; HBsAg levels continued to decline during the treatment period and further decreased after the end of treatment. (b) Treatment responses (HBsAg response, virological response, and biochemical response) at the end of treatment and 48 weeks post-treatment in the analysis including patients with NA administration considered to have no HBsAg response.

Time-course changes in serum HBV DNA, HBsAg and ALT levels of the three patients who achieved HBsAg clearance.

(a) 49-year-old man, HBeAg-negative, genotype C. (b) 41-year-old woman, HBeAg-negative, genotype C. (c) 44-year-old man, HBeAg-negative, genotype C. *The point of HBsAg clearance

A comparison of HBsAg kinetics during Peg-IFN α-2a monotherapy between HBsAg responders and non-responders in all patients, including those who were treated with NA during the follow-up period.

In the analysis including patients with NA administration considered to have no HBsAg response, the HBsAg changes from baseline at the end of treatment were compared between patients with and without an HBsAg response at 48 weeks post-treatment.

A comparison of the time-course changes in serum ALT levels and prevalence of ALT increase during Peg-IFN α-2a monotherapy between HBsAg responders and non-responders in all patients, including those treated with NA during the follow-up period.

In the analysis including the patients with NA administration considered to not have an HBsAg response, the serum ALT levels in HBsAg responders were more elevated than those in HBsAg non-responders. The proportion of patients showing an ALT increase during treatment was significantly higher among HBsAg responders than among HBsAg non-responders.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all physicians in all institutions who were involved in the treatment of patients.

References

Articles from Internal Medicine are provided here courtesy of Japanese Society of Internal Medicine

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.5432-20

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/internalmedicine/60/4/60_5432-20/_pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Predicting clinical outcomes in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving nucleoside analogues and pegylated interferon alpha: a hematochemical and clinical analysis.

BMC Infect Dis, 24(1):1149, 13 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39396949 | PMCID: PMC11472561

Cases of Rapid Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Reduction after COVID-19 Vaccination.

Intern Med, 62(1):51-57, 19 Oct 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36261382 | PMCID: PMC9876716

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Kinetics of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Level in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients who Achieved Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Loss during Pegylated Interferon Alpha-2a Treatment.

Chin Med J (Engl), 130(5):559-565, 01 Mar 2017

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 28229987 | PMCID: PMC5339929

[HBsAg loss with Pegylated-interferon alfa-2a in hepatitis B patients with partial response to nucleos(t)-ide analog: new switch study].

Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi, 26(10):756-764, 01 Oct 2018

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 30481882

Effect of switching from treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogs to pegylated interferon α-2a on virological and serological responses in chronic hepatitis B patients.

World J Gastroenterol, 22(46):10210-10218, 01 Dec 2016

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 28028369 | PMCID: PMC5155180

Adefovir dipivoxil and pegylated interferon alfa-2a for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and economic evaluation.

Health Technol Assess, 10(28):iii-iv, xi-xiv, 1-183, 01 Jan 2006

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 16904047

ReviewBooks & documents Free full text in Europe PMC