Abstract

Free full text

Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology

Abstract

Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS). They are the end product of a cell lineage which has to undergo a complex and precisely timed program of proliferation, migration, differentiation, and myelination to finally produce the insulating sheath of axons. Due to this complex differentiation program, and due to their unique metabolism/physiology, oligodendrocytes count among the most vulnerable cells of the CNS. In this review, we first describe the different steps eventually culminating in the formation of mature oligodendrocytes and myelin sheaths, as they were revealed by studies in rodents. We will then show differences and similarities of human oligodendrocyte development. Finally, we will lay out the different pathways leading to oligodendrocyte and myelin loss in human CNS diseases, and we will reveal the different principles leading to the restoration of myelin sheaths or to a failure to do so.

General introduction

Most of our knowledge about the biology of oligodendrocytes and myelin derives from studies in rodents. This fact can be easily explained, since cells or tissue slices of these animals are readily available and can be easily cultured, and since a large number of genetically modified animals allows it to dissect the function of individual proteins in the proper spatial and temporal context of development and disease. Studies in rodents led to the identification of important principles of oligodendrocyte development and myelin formation.

The development of oligodendrocytes and myelin—a rodent's perspective

Spinal cord and brain contain different subclasses of oligodendrocytes which derive from multiple sources

In the spinal cord, most oligodendrocytes derive from a specialized domain of the ventral ventricular zone, which first gives rise to motor neuron precursors, and then, after the neurogenic/gliogenic switch, to oligodendrocyte precursor cells/progenitors (OPCs) [107, 181, 183, 214]. From there, OPCs migrate all through the spinal cord and finally differentiate into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes. Later, an additional source of OPCs arises in the dorsal spinal cord, contributing to 10–15% of the final oligodendrocyte population in the spinal cord [25, 49, 195].

In the forebrain, the first OPCs originate in the medial ganglionic eminence and anterior entopeduncular area of the ventral forebrain. These OPCs populate the entire embryonic telencephalon including the cerebral cortex, and are then joined by a second wave of OPCs derived from the lateral and/or caudal ganglionic eminences. The third wave of OPCs, finally, arises within the postnatal cortex [86]. These different populations of OPCs are functionally redundant: When any one of them is destroyed at source by the targeted expression of a toxin gene in mice, the remaining cells spread into the vacant territory and restore the normal distribution of OPCs. As a result of this, a normal complement of oligodendrocytes and myelin can be produced, and the mice develop, survive, and behave normally [86]. In spite, or maybe even due to this functional redundancy, the different OPC populations seem to be fierce competitors.

Different OPC lines compete with each other during development

In the developing rodent spinal cord, the competition is won by OPCs derived from the ventral ventricular zone: These cells represent the first wave of cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage generated in the spinal cord, and eventually give rise to 85–90% of the final oligodendrocyte population found in this organ [25, 49, 195]. In this case, competition for limiting quantities of growth factors like platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) might be a determining factor for winning the competition [9, 26, 196].

In the developing forebrain, however, the situation seems to be quite different. Here, the competition is clearly lost by the first wave OPCs: although these cells are the first to distribute and to occupy vacant territories, their contribution to the total OPC population rapidly declines, until they are almost completely eliminated from the adult forebrain.

The reasons for the eventual loss of one OPC population in the developing forebrain remain completely unclear, and one can only speculate about possible causes and consequences [157].

According to such speculations, the first wave of forebrain OPCs emerging from the medial ganglionic eminence and the anterior entopeduncular area might represent the most “primitive source” of oligodendrocytes, a relic that lost its importance during evolution, when new sources of OPCs developed in the expanding brain. This assumption is supported by the observation that birds, which have much less cortical volume than mammals derive their OPCs only from the anterior entopeduncular area [157]. Alternatively, the first wave OPCs could be lost in the course of a (not yet demonstrated) oligodendrocyte turnover, or as a result of changes in the availability/responsiveness to growth and differentiation factors. Moreover, they might become dispensable if they have functions during development, that are not required in the adult [157].

No matter whether OPCs belong to the first, second, or third wave of cells, they have one point in common: They have to travel long distances in order to end up in their final place of destination. This migration is tightly controlled.

OPC migration is guided by regulatory signals

To date, three different classes of secreted molecules seem to be involved in the migration of OPCs: growth factors like PDGF, FGF [155, 174] or hepatocyte growth factor [211, 138]; chemotropic molecules like netrins and secreted semaphorins [74, 193]; and the chemokine CXCL1 [37]. Although there is no doubt that these factors play a role in OPC migration, the exact mode of action of these factors is still a matter of controversy, in part due to differences in experimental models, culture systems, and time points studied.

OPC migration is not only controlled by secreted molecules, but is also regulated by contact-mediated mechanisms involving many different extracellular matrix proteins and cell surface molecules [52, 88, 199], N-cadherins [125, 133, 145, 167, 190], and possibly even additional, yet unidentified molecules.

From all these different molecules, a common theme evolves, demonstrating contact-based migration of OPCs over extracellular matrices, axonal tracts, and astrocytic surfaces [37]. Once located at their final destination, some OPCs persist into adulthood (see Appendix 1), while the vast majority differentiates to myelin-producing oligodendrocytes.

The differentiation of OPCs to oligodendrocytes and the onset of myelination are spatially and temporally regulated

This process involves signaling processes between the Notch1 receptor, its ligand Jagged 1 located on the axonal surface [55], and γ-secretase [150, 202]. Interestingly, oligodendrocytes have only a brief period of time for myelination early during differentiation, and are relatively incapable of myelinating once they are mature [202]. Moreover, the ensheathment of multiple axons by a single oligodendrocyte is a highly coordinated event: oligodendrocytes do not ensheath different axons sequentially at different time points, but are done within a brief window of time, typically within 12–18 h [8, 202].

Oligodendrocytes do not randomly wrap plasma membrane around neuronal processes

Oligodendrocytes select axons with diameters above 0.2 μm [171]. The molecular cues for this recognition remain unknown. In the peripheral nervous system, the critical axonal signal for myelination by Schwann cells is provided by neuronal neuregulin-1 (NRG1) type III, interacting with glial ErbB receptors, and it was thought for a long time that NRG1/ErbB signaling might also regulate myelination in the CNS. This point of view was supported by the observation that not only Schwann cells, but also oligodendrocytes express erbB receptors (oligodendrocytes erbB2 and erbB4, Schwann cells erbB2 and erbB3, but only little erbB4 [197]). It was further observed, that oligodendrocytes fail to develop in spinal cord explants derived from mice lacking neuregulin [198], that erbB2 is required for the development of terminally differentiated spinal cord oligodendrocytes [141], and that erbB2 plays a role in governing the properly timed exit from the cell cycle during development into myelinating oligodendrocytes [89]. Moreover, mice with dominant negative erbB4 have more differentiated oligodendrocytes, but each of them seems to myelinate less axonal surface and to produce thinner myelin sheaths than its wild-type counterpart [159]. And last, mice haploinsufficient for type III NRG1 are hypomyelinated in the brain, and normally myelinated in the optic nerve and spinal cord [187]. However, recent observations challenge the assumption that NRG1/ErbB signaling might also regulate myelination in the CNS. Instead, they suggest that NRG1/ErbB signaling serves distinct functions in myelination of the peripheral and central nervous system [19]: Mice completely lacking NRG1 beginning at different stages of neural development assemble normal amounts of myelin, on schedule [19]. When neuregulin signaling is completely abolished in oligodendrocytes of double mutants lacking ErbB3 and ErbB4 (and carrying ErbB2 without ligand-binding activity), CNS axons are nevertheless myelinated without delay, and at the same level as in control mice, at least until postnatal day p11, the latest time point studied [19]. However, while myelination was not delayed even in the absence of NRG1, there was clear evidence for premature, and even for hyper-myelination in NRG1 type III overexpressing mice [19]. Cumulatively, these data suggest that normal myelination occurs independently of NRG1 signaling in vivo. They also demonstrate that excess NRG1 can initiate the myelination program in CNS development, but that this function is normally provided by different, still unknown axonal signaling systems.

Myelination is a regulated process

The data summarized above led to the conclusion that the onset of CNS myelination in normal development might be determined by the degree of neuronal differentiation, and not by the timing of an intrinsic oligodendrocyte differentiation program [19].

One essential signal for the onset of myelination seems to be provided by the electrical activity of neurons. For example, the optic nerves of mice which had been reared in the dark developed fewer myelinated axons than control optic nerves [62], optic nerves of naturally blind cape-mole rats are hypomyelinated [139], and blockade of sodium-dependent action potentials in developing optic nerves inhibits myelination [38]. Vice versa, increasing neuronal firing with α-scorpion toxin enhances myelination [38], and premature eye opening accelerates myelination in rabbit optic nerves [186]. Action potential firing leads to the release of ATP [177] and adenosine [96, 115], which can mediate neuron-glial communications. In the CNS, adenosine inhibits the proliferation of OPCs, stimulates their differentiation, and promotes the formation of myelin [178]. The ATP released from axons firing axon potentials does not directly act on OPCs or oligodendrocytes. Instead, it triggers the release of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) from astrocytes, which promotes myelination by mature oligodendrocytes [67]. This fact could explain why LIF−/− mice display impaired myelin formation [23], and why interfering with astrocyte biology leads to myelin abnormalities, as seen in mice with knock-out of the astrocytic protein GFAP [104], and in patients with Alexander disease, a fatal white matter disorder of childhood caused by mutations in the GFAP gene [124].

Although the electrical activity of neurons in the CNS is an essential promyelinating factor, additional changes on axons seem to be needed to drive efficient myelin formation. Some of these changes seem to be induced by electrical activity as well. For example, during development, all growing nerve fibers express the polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM), which prevents homophilic NCAM–NCAM adhesion and, more generally, cell–cell interactions. Only when this form of NCAM is downregulated, as it is in electrically active neurons [91, 97], myelination can proceed [32]. Another molecule correlating with the extent of oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination is LINGO-1, a transmembrane protein with leucine-rich repeats and an immunoglobulin domain expressed in neurons and oligodendrocytes. Loss of LINGO-1 function in oligodendrocytes leads to increased myelination, whereas its overexpression inhibits myelin formation [122].

There are certainly more, yet unidentified molecular mechanisms enabling oligodendrocytes to recognize, ensheath, and wrap axons [8].

Myelin assembly is under neuronal control

The window of time available for the onset of myelination seems to be very narrow, in the range of 12–18 h during which oligodendrocytes have to wrap layer after layer of plasma membrane around multiple axons [8]. Hence, they have to synthesize, sort, and traffick an enormous amount of proteins in short time. The machinery for these processes is rather complex. For example, one major myelin protein, myelin basic protein (MBP, Table 1), is targeted by transport of its mRNA. The MBP mRNA is assembled into granules in the perikaryon of oligodendrocytes, transported along processes, and then localized to the myelin membrane [2, 3]. The other major protein, proteolipid protein (PLP)/DM20 is transported to myelin by vesicular transport through the biosynthetic pathway. Two different observations suggest that both delivery systems might be under the control of neuronal signals.

Table 1

Markers for oligodendrocytes in paraformaldehyde-fixed brain tissue

| Protein | Developmental stage | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonic anhydrase II | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Not only oligodendrocytes interspecies differences | [15, 87] |

| CNP | OPC, differentiated oligodendrocytes | Highly specific and reliable; tolerates prolonged fixation poorly | [1, 22] |

| GalC | Differentiating OPC, mature oligodendrocytes | PFA/cryo-sections only | [207, 208] |

| Kir4.1 | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Also in astrocytes | [77, 132] |

| MBP | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Mainly myelin, in oligodendrocytes only during active remyelination | [1, 22] |

| MAG | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Periaxonal loop of oligodendrocyte processes in mature myelin, heavily expressed in myelinating oligodendrocytes | [1] |

| MOG | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Mainly myelin, surface labeling of mature oligodendrocytes | [1, 22] |

| NG2 | OPC | PFA/cryo; positive in OPCs in well fixed experimental and biopsy material; frequently lost in autopsy material; autolysis sensitive | [85] |

| Nkx2.2 | High in OPC, low in mature oligodendrocytes | [94] | |

| Nogo A | Mature oligodendrocytes | [94] | |

| O4 | OPC, mature oligodendrocytes | PFA/cryo-sections only | [207] |

| Olig2 | High in OPC, low in mature oligodendrocytes | [94] | |

| PLP | Differentiated oligodendrocytes | Mainly myelin, in oligodendrocytes only during active remyelination | [143] |

| RIP | Myelinating oligodendrocytes | [13] | |

| TPPP/p25 | Myelinating oligodendrocytes | Mature oligodendrocytes, highly reliable in human tissue | [58, 146] |

First, oligodendrocyte cultures without neurons express MBP, PLP, and galactosylceramide (GalC). However, under these conditions, PLP is predominantly intracellularly localized, and shows only little co-localization with MBP or GalC in the membrane sheets. In coculture with neurons, however, PLP, MBP, and GalC are co-localized. This rearrangement of the oligodendroglial plasma membrane is critically dependent on the presence of MBP. MBP seems to act as a lipid coupler by bringing the different layers of myelin in close position (a process termed “vertical membrane coupling”), and by clustering the lipid bilayer in lateral dimensions (“horizontal membrane coupling”). This neuron- and MBP-dependent clustering mechanism might be responsible for the concentration of membrane components within myelin [48].

Second, in the absence of neurons, PLP is produced by oligodendrocytes, but immediately internalized by endocytosis. After receiving neuronal signals, the rate of endocytosis is reduced, and PLP is transported from the late endosomes/lysosomes to the plasma membrane by exocytosis [192]. This regulation of PLP trafficking might represent a mechanism to store membrane produced in advance, before the onset of myelination, and to release this membrane on demand in a regulated fashion [171] (Fig. 1).

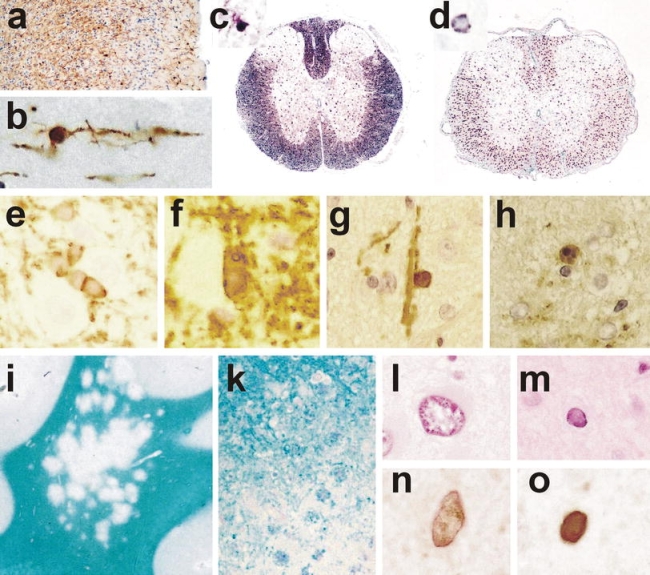

a–d Detection of oligodendrocytes in paraffin embedded tissue sections. a Mouse cortex, stained by immunocytochemistry for CNPase shows numerous process bearing oligodendrocytes and staining of myelin sheaths, ×120; b high magnification of a CNPase positive oligodendrocyte in the mouse cortex (layer I), showing a small round cell body and few cell processes connected to myelin sheaths, ×1,000; c rat spinal cord stained by in situ hybridization for myelin basic protein mRNA; staining is seen in the cell bodies (e.g., in the gray matter) as well as in oligodendrocyte processes associated with myelin sheaths (dark staining in the white matter), ×50; d rat spinal cord stained by in situ hybridization for proteolipid protein (PLP); the mRNA for PLP is only located within the perinuclear cytoplasm, there is no staining of myelin, ×50; e–h oligodendrocyte pathology in transgenic animals overexpressing proteolipid protein; e and f hemizygous animal, which shows normal myelination, stained by immunocytochemistry for PLP; in the normal animal PLP protein is rarely detected in the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes; in hemizygous PLP transgenic animals a variable extent of PLP expression is seen in the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes (e), and this is associated with aberrant formation of myelin-like structures within and adjacent to the cells (f); g–h homozygous animal, which shows extensive dys-myelination; only few oligodendrocytes are preserved, which are connected to myelin sheaths and contain abundant PLP immunoreactivity in their cytoplasm (g); some of the PLP reactive oligodendrocytes show nuclear condensation and fragmentation, consistent with apoptosis (h), ×1,200; i–o neuropathology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; i multiple small confluent demyelinating lesions in the white and gray matter, giving the impression of a moth eaten pattern of demyelination (×2); k edge of an active demyelinating lesion with numerous macrophages, containing recent (luxol fast blue positive) degradation products; l and m pathologically altered nuclei in PML showing giant nuclei of astrocytes (l) and small oligodendrocyte nuclei with intranuclear inclusion (m); n and o similar nuclei, as shown in l and m contain virus antigen as revealed by immunocytochemistry; ×1,200

The development of oligodendrocytes and myelin—what is similar/different in humans?

The key findings of rodent oligodendrocyte development and myelin formation described above include: (1) a common progenitor cell for neurons and oligodendrocytes; (2) a ventral to dorsal progression of oligodendrogenesis; (3) multiple origins of oligodendrocytes; (4) the dependency of differentiation and migration on regulatory factors; and (5) the interrelationship between axonal signaling and myelination.

In general, all these principles seem to apply to the human system as well, although evidence for it is mostly circumstantial and beyond the scope of this review to discuss. Instead, we refer the reader to an excellent review on this matter [72], and select for further demonstration just one particularly important aspect: data indicating that also human oligodendrocytes have multiple origins. These data derive from studies of the human fetal forebrain at midgestation, and reveal the simultaneous presence of three different OPC populations [70, 71, 152]. The first population consists of cortical OPCs which express Dlx2 and Nkx2.1 [152], typical transcription factors of ventrally derived OPCs in rodents [72]. The second population consists of OPCs which do not express Dlx2 and Nkx2.1 and most likely represent dorsally derived oligodendrocytes in the human brain [152]. The third population, finally, expresses typical OPC markers like PDGFRα, NG2, and Olig1, and is found in a stream of cells migrating between the ganglionic eminences and cortical subventricular zone [152]. As in rodents, it remains unclear whether oligodendrocytes from these different sources have different roles, myelinate different axonal pathways, or affect the outcome of CNS pathologies.

Since our knowledge about human oligodendrocyte biology is limited, results from rodent studies are often extrapolated to the human situation. However, several essential differences between the rodent and the human brain strongly argue against such a simple and uncritical approach:

Key regions of the human brain might be underdeveloped in rodents and vice versa. For example, humans have neocortical regions which are completely lacking in mice, while prominent structures of the rodent brain, the olfactory bulbs, are underdeveloped in humans [72].

The time scale for myelination is different between humans and rodents. Due to the greater complexity of the human brain, myelination in the human forebrain takes decades, compared to weeks in rodents [126].

The sheer numbers of oligodendrocytes in humans are dramatically increased (although the density of oligodendrocytes per mm3 is remarkably similar between rodents and humans) [140, 176].

Human and rodent OPCs might respond differently to certain factors [6, 168, 205, 213]. This can be shown best in the case of CXCL1. Approximately 85% of all rodent OPCs carry receptors for CXCL1 [37], while only very few human OPCs do so [47]. Hence, CXCL1 can act directly on rodent OPCs, but has an indirect mode of action in humans, where it induces astrocytes to secrete OPC mitogens [47].

Consequences of myelination

Oligodendrocytes not only ensheath axons to electrically insulate these structures, but also induce a clustering of sodium channels along the axon, at the node of Ranvier, which is one important prerequisite for saltatory nerve conduction [78, 79]. Even normal axonal transport processes and neuronal viability seem to depend on proper myelination, since axons with modified myelin sheaths have altered axonal transport rates and changes in the microtubule number or stability [45, 90], or are swollen and show signs of degeneration [44, 53, 60, 82, 83, 98, 194]. The presence of intact myelin sheaths could even lead to an increase in axon diameter [35, 116, 161], possibly mediated by the local accumulation and phosphorylation of neurofilament [161, 162]. And last, oligodendrocytes can provide trophic support for neurons by the production of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [203], brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [41], or insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) [42].

Oligodendrocyte metabolism as risk factor for oligodendrocyte pathology

It has been estimated that during the peak of myelination, oligodendrocytes elaborate about three times its weight in membrane per day, and eventually support membrane up to 100× the weight of its cell body [36, 111, 120, 121]. This particular feature renders oligodendrocytes vulnerable at several different “Achilles′ heels”.

First, in order to myelinate properly, oligodendrocytes must have extremely high metabolic rates, and must consume large amounts of oxygen and ATP [121]. The production of ATP leads to the formation of hydrogen peroxide as a toxic byproduct, and a high cellular metabolism also creates reactive oxygen species, both of which must be properly metabolized [121]. Second, myelination is under control of many myelin synthetic enzymes, which require iron as a co-factor [36]. This may contribute to the observation that OPCs and oligodendrocytes have the largest intracellular stores of iron in the brain [34, 189], which can, under unfavorable conditions, evoke free radical formation and lipid peroxidation [18, 76]. On top of this, oligodendrocytes have only low concentrations of the anti-oxidative enzyme glutathione [189]. And last, during myelination, the capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum to produce and fold proteins properly seems to be a cellular “bottle neck”, since even slight variations in the amount of a single protein can mess up the entire system and result in the retention, misfolding, and accumulation of many other proteins in this oligodendrocytic organelle [10, 16].

Taken together, just being an oligodendrocyte seems already enough to put these cells at greater risk of damage under pathological conditions.

Mechanisms of oligodendrocyte death

Due to the combination of a high metabolic rate with its toxic byproducts, high intracellular iron, and low concentrations of the antioxidative glutathione, oligodendrocytes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage [76, 189]. Hence, oxidative damage is a common contributor to oligodendrocyte loss under many pathological conditions like MS and ischemia. It can act in concert with the sphingomyelinase/ceramide pathway: ceramide is the core component of sphingolipids, the major lipid components of myelin sheaths [11]. It is released by the action of sphingomyelinase which is normally inactive, but gets activated in response to oxidative stress [73, 172], inflammatory mediators [20, 172, 188], injury or infection [165]. Once released within oligodendrocytes, ceramide can activate pro-apoptotic signaling cascades eventually culminating in oligdendrocyte loss [20, 121].

Oligodendrocytes also express an arsenal of molecules rendering them susceptible to excitotoxic cell death [40, 103, 117, 119, 163]: they carry AMPA [184], kainate [4, 163], and NMDA [80, 123, 160] receptors which make them vulnerable to glutamate toxicity, and the ATP receptor P2X7 [118] which predisposes them to the damaging action of sustained levels of extracellular ATP [118].

Oligodendrocyte loss can also occur as a result of exposure to inflammatory cytokines. For example, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) can induce apoptosis of oligodendrocytes by binding to their p55 TNF receptor [75]. The situation is more complex in the case of interferon gamma (IFNγ). This cytokine is highly toxic for actively proliferating OPCs, much less so for immature oligodendrocytes, and not at all for mature oligodendrocytes [65]. Besides these direct actions, inflammatory mediators may also damage oligodendrocytes indirectly through stimulation of radical production in microglia and possibly also in astrocytes. Oxygen- and nitric oxide-radicals are particularly toxic for mitochondria through interaction and blockade of various proteins of the respiratory chain [113, 173]. Indeed, recent studies on changes of gene expression in glia cells revealed that many different pro-inflammatory cytokines can induce mitochondrial injury [106].

As mentioned above, oligodendrocytes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage and mitochondrial injury. This is probably reflected by the profound oligodendrocyte damage in certain toxic states, which interfere with mitochondrial function. Examples for this are the selective oligodendrocyte apoptosis and demyelination induced by cuprizone, a copper chelator interfering with complex IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain [191], and by the intoxication with cyanides also blocking the respiratory chain at the level of complex IV [27, 63].

All these mechanisms described above do not destroy oligodendrocytes specifically, but may also impair function and viability of other cells, such as neurons and astrocytes. However, oligodendrocytes and their myelin sheaths are in general more susceptible to damage than other cellular components of the nervous system. This explains the so-called “bystander damage” of myelin and oligodendrocytes observed in many inflammatory disease states, in which the immune reaction is not specifically directed against these cells [206]. In fact, demyelination and oligodendrocyte death is a common feature of inflammatory white matter lesions, both in humans and experimental models. A particularly illustrative example is Devic’s neuromyelitis optica (NMO). This disease has originally been classified as an inflammatory demyelinating disease due to the presence of widespread primary demyelination in the spinal cord and optic nerves [110]. Recent immunological studies, however, provide clear evidence that the primary targets of the pathogenic immune (autoantibody) response in NMO are not oligodendrocytes, but astrocytes [100, 101]. Time course studies on lesion development in NMO patients revealed that astrocytes are destroyed first, but that this is followed by profound demyelination and oligodendrocyte, axons and nerve cells destruction [127, 128, 158]. Whether oligodendrocyte injury in this disease is only a bystander reaction of the inflammatory process or whether specific disturbance of the homeostatic interaction between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes plays an additional role, is currently unresolved.

Besides by non-specific bystander mechanisms, oligodendrocytes can also be destroyed by specific, cell selective immune mechanisms. Autoantibodies directed against an epitope on the extracellular surface of myelin or oligodendrocytes can induce demyelination either through activation of complement or through their recognition by Fc-receptors of activated macrophages. The most compelling examples for such autoantibodies are those directed against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG, [105]) and galactocerebroside [43]. Antibody-mediated demyelination is an important mechanism in models of autoimmune encephalomyelitis and seems to play a role also in a subset of patients with MS-like inflammatory demyelinating diseases [109, 137]. Similarly, cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, directed against a myelin or oligodendrocyte antigen, or against a foreign (e.g., virus) antigen expressed in oligodendrocytes, can induce oligodendrocyte apoptosis, followed by selective demyelination [66, 130, 164]. As other glia cells and neurons, oligodendrocytes are able to express major histocompatibility (MHC) class I antigens under inflammatory conditions, which is an essential pre-requisition for antigen recognition and cytotoxicity by MHC class I restricted cytotoxic T-cells [64].

Different pathological patterns of white matter injury reflect different pathogenetic mechanisms of myelin and oligodendrocyte damage

Although pathogenetic events that target myelin and oligodendrocytes invariably result in primary demyelination, the structural patterns of tissue injury in the initial stages of lesion formation differ, depending upon the mechanism involved. Three main patterns of tissue injury can be differentiated.

Simultaneous destruction of oligodendrocytes and myelin

If the inciting injury is simultaneously directed against myelin and oligodendrocytes, sharply demarcated plaques of primary demyelination are induced [180]. Myelin sheaths are completely lost, while oligodendrocyte cell bodies may be partly preserved within active lesion areas. The paradigmatic example for such a mechanism is demyelination triggered by specific antibodies against MOG, an antigen expressed in highest density at the peripheral processes of oligodendrocytes covering the myelin sheath [22]. Upon binding of these antibodies, myelin sheaths are disintegrated by vesicular dissolution in case of massive complement deposition [54] or by phagocytosis of myelin fragments by macrophages (antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity [21]. Acute injury of oligodendrocytes follow the pathway of necrosis. However, mature oligodendrocytes which have lost their myelin sheaths but survived the initial attack are then slowly removed from the lesions by apoptosis [208]. Following these initial changes, sharply demarcated focal demyelinated lesions are formed. A similar pattern of lesion formation is also seen when myelin and oligodendrocytes are destroyed through antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cells [164] or non-selectively by toxic products of activated macrophages (bystander demyelination). Under the latter conditions, however, the demyelinated lesions are associated with much more widespread damage to other cellular components as well, in particular axons.

Primary oligodendrocyte injury

Distinct types of lesions are seen, when the primary injury is due to a metabolic disturbance of oligodendrocytes, not directly affecting myelin. In this situation, demyelination is frequently incomplete. Such lesions not only contain areas of complete demyelination, but also diffuse myelin pallor is observed. At the edges of the lesions, a moth eaten pattern of demyelination is observed which may reflect the loss of single oligodendrocytes with their respective myelin sheaths. This pattern of demyelination is mainly seen in conditions of infections, which target oligodendrocytes, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In such conditions, virus antigen is abundant in oligodendrocytes and the cells are destroyed both by apoptosis or necrosis [129]. Toxic damage of oligodendrocytes, for example by cuprizone results in similar patterns of demyelination [191].

Demyelination and oligodendrocyte damage induced by mitochondrial injury and/or energy deficiency

Energy deficiency in the white matter leads to a fundamentally different pattern of tissue injury. Also in this condition, oligodendrocytes are highly vulnerable, but they die by a process termed “distal/dying back oligodendrogliopathy”. In initial lesions, the most severely damaged parts of the cells are the most distal (periaxonal) oligodendrocyte processes [1]. This is reflected by a selective loss of proteins, which are predominantly located in this location, such as myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiester [1, 68]. Conventional staining for myelin with luxol fast blue shows a diffuse or focal myelin pallor, while immunocytochemistry for proteins located within compact myelin (myelin basic protein or proteolipid protein) is unaffected. With progression of the lesions the majority of oligodendrocytes reveal nuclear condensation and in part nuclear fragmentation in the absence of the expression of activated caspase 3 (caspase independent apoptotic like cell death). Additional characteristic features of such lesions are the preferential destruction and loss of small caliber axons and a remarkable preservation of axons and myelin around larger blood vessels (arterioles and veins). Such tissue changes are the hallmark of initial ischemic lesions of the white matter, and occur within the first hours or days in a white matter stroke lesion [1]. Similar lesions, however, can also be seen in severe inflammatory brain lesions, for example in a subset of patients with acute multiple sclerosis or with virus infections of the white matter like herpes simplex virus encephalitis, cytomegalovirus encephalitis, or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy [1]. In the latter lesions, energy deficiency is associated with profound mitochondrial damage, which may at least in part be induced by disturbance of the mitochondrial respiratory chain through reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [114]. Upregulation of molecules which are induced by (hypoxic) tissue preconditioning, such as hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha or stress proteins in the periphery of such lesions may exert local neuroprotective effects. Moreover, tissue areas with increased resistance to energy deficiency may alternate in the periphery of the lesions with more vulnerable areas, and can give rise to concentric layering of demyelinated and preserved tissue zones typically found in the lesions of Balo’s type of concentric sclerosis [175] (Fig. 2).

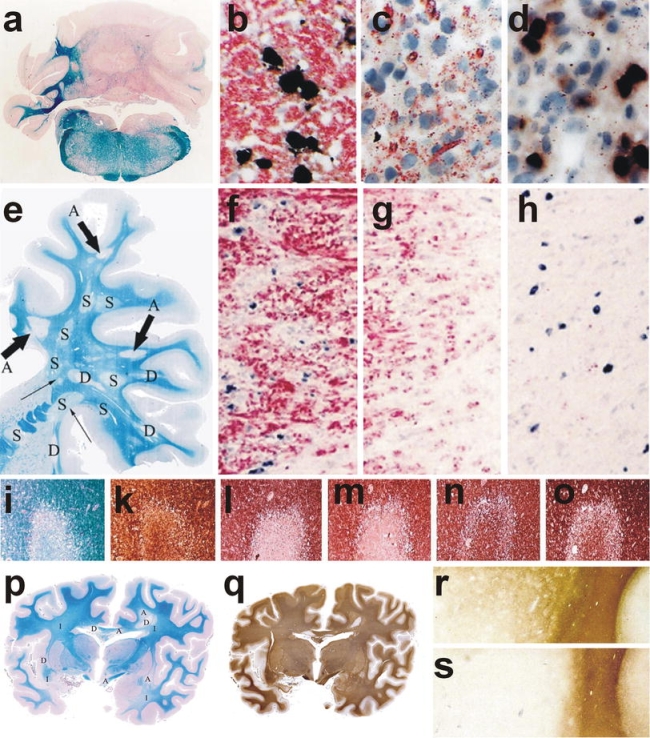

Myelin and oligodendrocyte pathology in autoimmune encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, and stroke. a–d Chronic autoimmune encephalomyelitis, induced in DA rat by active sensitization with MOG fusion protein; a massive demyelination is seen in the cerebellar white matter, ×6; b–d oligodendrocytes in different lesion stages of EAE; in the peri-plaque white matter myelin (red) is present and multiple oligodendrocytes with PLP mRNA (black) are seen (b); in the active lesions myelin falls apart, myelin fragments are taken up by macrophages (red granules) and oligodendrocytes are lost (c); in more advanced lesions no macrophages with early myelin degradation products are present; numerous oligodendrocytes re-appear in the lesions, apparently recruited from progenitor cells (black cells), followed by rapid and extensive remyelination; immunocytochemistry for PLP and in situ hybridization for PLP mRNA, ×1000; e–h chronic multiple sclerosis case with extensive remyelination within the CNS; This hemispheric brain section contains 3 active lesions, 4 demyelinated plaques, and 8 remyelinated shadow plaques, ×1.2; f–h double staining for PLP protein (red) and PLP mRNA (black) in one of the active lesions shows a similar pattern as described before in EAE; many oligodendrocytes in the peri-plaque white matter (f); oligodendrocyte loss in the zone of active demyelination (g) and reappearance of oligodendrocytes in the inactive zone, closely adjacent to the zone of activity (h), ×500; i–o myelin changes in the initial stage of a lesion in white matter stroke; LFB shows pale myelin staining (i); the axons, stained with Bielschowsky silver impregnation are largely preserved (k); MAG (l) and CNPase (m) are completely lost from the lesions, while the myelin proteins within the compact sheath (PLP; n) or on the oligodendrocyte surface (MOG; o) are preserved, ×20; p–s acute multiple sclerosis with lesions following a pattern of hypoxia-like tissue injury (Pattern III, [109]). p The section contains areas of initial demyelination (i), early active demyelination (a) and late active or inactive portions (d); q serial section of p, stained by immunocytochemistry for PLP; Only the late active and inactive lesions show loss of PLP; in the active portions (a) a minor loss of PLP reactivity is seen, while in the initial lesions PLP reactivity is the same as in the normal appearing white matter, ×3; r and s edge of an active lesion showing partial preservation of immunoreactivity for MOG (r), but extensive and complete loss of MAG(s), ×20

It has to be emphasized that these distinct patterns of demyelination segregate well in the initial stages of lesion formation and in patients with rapidly progressive white matter disease. However, in more slowly expanding lesions, these morphological features may in part be lost. Then, it may become difficult to determine the mechanism of tissue injury purely on morphological grounds. The final outcome of all the lesions described above is focal or diffuse areas of primary demyelination in the white matter.

Remyelination

Remyelination, the restoration of new myelin sheaths to demyelinated axons, is not performed by pre-existing mature oligodendrocytes [84, 144, 170, 185], but involves in most cases the generation of new mature oligodendrocytes from the adult, quiescent OPC pool distributed throughout the CNS [28, 46, 56, 61, 102, 136, 200, 201, 212]. In the corpus callosum, remyelinating oligodendrocytes can also be derived from stem and precursor cells of the adult subventricular zone [50, 131]. The process of remyelination takes place in several different steps. First, local adult OPCs must switch from an essentially quiescent state to a regenerative phenotype [50]. This transition seems to be triggered by factors derived from activated microglia cells and astrocytes [57, 156], and not by the demyelination per se [134], and leads to OPC proliferation and recruitment to demyelinated areas [50]. Then, the differentiation of OPCs to remyelinating oligodendrocytes starts. All following steps—the interactions with unmyelinated axons, the expression of myelin genes, the elaboration, wrapping and compacting of myelin membrane to form myelin sheaths are similar in myelinating OPCs during development, and in remyelinating OPCs during the regenerative process [50]. However, some differences between myelination and remyelination exist:

Adult OPCs have a longer cell cycle time and a slower rate of migration [209].

The requirements for transcription factor usage seem to be different. Studies in genetically modified mice clearly revealed that the lack of the oligodendrocyte-lineage specific transcription factor olig1 is incompatible with myelination of the brain [210]. However, when this lack is compensated by the overexpression of the oligodendrocyte-lineage specific transcription factor olig2 (as was probably the case in earlier studies, due to the usage of a particular gene targeting cassette [107, 210]), the mice were able to myelinate during development [7], but were unable to repair demyelinated lesions by remyelination [7].

Notch, the regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation in development (see above), is dispensable during remyelination [179].

The correlation between axon diameter and myelin sheath thickness and length seen during developmental myelination is less apparent in remyelination, resulting in thinner and shorter sheath segments [50, 112]. The mechanisms underlying this observation remain unclear, but could involve signals obtained from dynamically growing and changing axons with a need for myelination along their entire length during development, or from mature axons focally lacking myelin sheaths during remyelination [50].

Thus, the pathological hallmark of remyelination in the CNS is the presence of axons with unusually thin myelin sheaths in relation to their caliber [182]. This is best seen by an increase of the G-ratio (the ratio between axonal diameter and myelinated fiber diameter). Unequivocal identification of remyelination in conditions of diffuse demyelination is possible at early stages, but very difficult in older established lesions. In the latter situation detailed quantitative electron microscopic studies may be necessary to show differences in the G-ratio in affected areas. In areas of focal demyelination, such as those occurring in multiple sclerosis, remyelination is reflected by shadow plaques (Markschattenherde, [166]). These are MS-typical focal, sharply demarcated white matter lesions, characterized by uniformly thin myelin sheaths [149].

Remyelination has been extensively studied in MS. In accordance with the basic concepts described above, the recruitment of OPCs and early remyelination is extensive in very early stages of demyelination, in lesions which are still infiltrated by macrophages and lymphocytes [99, 147, 151], and in plaques formed at early stages of the disease. In these fresh lesions, remyelination might be facilitated by inflammation and infiltrating macrophages which provide the tissue with growth factors [39, 92]. Remyelination largely fails at the later (progressive) stage of the disease [59]. This failure of remyelination may be additionally ascribed to age [153, 169], to age-associated changes in the growth factor responsiveness of adult OPCs, and to less efficient clearance of myelin debris from the lesions which has been shown to inhibit remyelination in experimental models [93, 169]. Progressive axonal loss in the lesions, an inability of demyelinated axons to interact with myelinating cells [33], or the presence of myelination inhibiting factors in the extracellular space [204] may additionally impair the capacity of remyelination. These speculations are further corroborated by the observations that mature oligodendrocytes found in active lesions slowly disappear from established lesions [208], and that the OPCs found in late demyelinated lesions seem to be impaired in their further differentiation to mature myelin forming oligodendrocytes [31, 94]. Moreover, it has also been observed that both the numbers and the differentiation stages of OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes are highly variable within lesions of different patients and in different lesion stages. This suggests that different mechanisms of demyelination may have different effects on the remyelinating capacity of lesions [108].

Thus, major efforts are invested to find new neuroprotective therapies, which stimulate myelin repair and by this halt progressive degeneration of chronically demyelinated axons. However, recent studies suggest that the situation in MS patients might be more complicated than previously anticipated. These studies show that extensive remyelination is even seen in a subset of patients, who died at the late progressive stage of the disease. The extent of remyelination in these patients was variable, depending upon the location of the plaques in the brain and spinal cord [142, 143]. Extensive remyelination was predominantly seen in forebrain lesions, located in the subcortical and deep white matter, while it was rather sparse in periventricular areas, the brain stem, and the spinal cord. These data indicate that the capacity of OPCs to differentiate into remyelinating cells is regionally different, possibly related to intrinsic differences in different oligodendrocyte populations as discussed above.

Another important factor is the instability of newly formed myelin in MS lesions, which still show inflammatory and demyelinating activity. New demyelinating activity in previously remyelinated shadow plaques has been unequivocally documented in MS [148], and areas of remyelination are more frequently affected by new inflammatory demyelination than the normal appearing white matter [17]. However, the instability of newly formed myelin in MS lesions also crucially depends on an active inflammatory environment. When inflammation subsides at very late stages of the disease [51], myelin repair seems to be long lasting and stable [143].

Conclusions

Oligodendrocyte biology, myelination, and maintenance of myelin sheaths are very complex processes and their disturbances are associated with major diseases of the nervous system. Intensive research efforts, performed during the last decades have clarified basic principles of these processes and offer new avenues for therapeutic interventions. Much less, however, is known so far on the exact role of these processes in the different diseases of the nervous system. Addressing these questions will be the major challenge for the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF, projects P 19854-B02 to H.L. and P 21581-B09 to M.B.).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix 1: Heterogeneity among adult OPCs

The adult OPCs express the proteoglycan NG2 and the PDGF receptor α [30, 85, 154, 170], and have been given numerous names like NG2-expressing OPCs [50], synantocytes [24], or polydendrocytes [135]. Current experimental evidence suggests that they might be less restricted in their differentiation potential and might not only give rise to oligodendrocytes, but also to neurons in the hippocampus [12] or to astrocytes [5, 29]. They are probably not only heterogenous in terms of the different cell types they can give rise to, but also seem to be heterogenous in function: while some of them become quiescent, others apparently have key physiological roles and are involved in the bi-directional communication between glial cells and neurons since they receive synaptic inputs [14, 69, 80, 95, 215] and are able to generate action potentials [81].

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0601-5

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00401-009-0601-5.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/1331023

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1007/s00401-009-0601-5

Article citations

Zebrafish as a Model for Multiple Sclerosis.

Biomedicines, 12(10):2354, 16 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39457666 | PMCID: PMC11504653

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Mechanisms of Transsynaptic Degeneration in the Aging Brain.

Aging Dis, 15(5):2149-2167, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39191395 | PMCID: PMC11346400

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Zuranolone therapy protects frontal cortex neurodevelopment and improves behavioral outcomes after preterm birth.

Brain Behav, 14(9):e70009, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39236116 | PMCID: PMC11376442

Glial Cells as Key Regulators in Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms Associated with Multiple Sclerosis.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(17):9588, 04 Sep 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39273535 | PMCID: PMC11395575

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Exposure to multiple ambient air pollutants changes white matter microstructure during early adolescence with sex-specific differences.

Commun Med (Lond), 4(1):155, 01 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39090375 | PMCID: PMC11294340

Go to all (454) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The role of oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitors in CNS remyelination.

Adv Exp Med Biol, 468:183-197, 01 Jan 1999

Cited by: 87 articles | PMID: 10635029

Review

Oligodendrocyte Development in the Absence of Their Target Axons In Vivo.

PLoS One, 11(10):e0164432, 07 Oct 2016

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 27716830 | PMCID: PMC5055324

Progressive remodeling of the oligodendrocyte process arbor during myelinogenesis.

Dev Neurosci, 18(4):243-254, 01 Jan 1996

Cited by: 50 articles | PMID: 8911764

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of CNS myelination.

Curr Opin Neurobiol, 20(5):601-607, 16 Jun 2010

Cited by: 62 articles | PMID: 20558055

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Austrian Science Fund FWF (4)

Susceptibility for inflammation of the immature CNS

Assoz. Prof. Dr. Monika BRADL, Medical University of Vienna

Grant ID: P 21581-B09

Innate immunity in the pathogenesis of initial MS lesions

Univ.Prof. Dr. Hans LASSMANN, Medical University of Vienna

Grant ID: P 19854

Innate immunity in the pathogenesis of initial MS lesions

Univ.Prof. Dr. Hans LASSMANN, Medical University of Vienna

Grant ID: P 19854-B02

Susceptibility for inflammation of the immature CNS

Assoz. Prof. Dr. Monika BRADL, Medical University of Vienna

Grant ID: P 21581

and

and