Abstract

Background

Implementation strategies are key to enhancing the translation of new innovations but there is a need to systematically design and tailor strategies to match the targeted implementation context and address determinants. There are increasing methods to inform the development and tailoring of implementation strategies to maximize their usability, feasibility, and appropriateness in new settings such as the Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies (CWIS) approach. The aim of the current project is to apply the CWIS approach to inform the redesign of a multifaceted selection-quality implementation toolkit entitled Adoption of Curricular supports Toolkit: Systematic Measurement of Appropriateness and Readiness for Translation in Schools (ACT SMARTS) for use in middle and high schools.Methods

We systematically applied CWIS as the second part of a community-partnered iterative redesign of ACT SMARTS for schools to evaluate the usability and inform further toolkit redesign areas. We conducted three CWIS user testing sessions with key end users of school district administrators (n = 3), school principals (n = 6), and educators (n = 6).Results

Our CWIS application revealed that end users found ACT SMARTS acceptable and relevant but anticipate usability issues engaging in the ACT SMARTS process. Results informed the identification of eleven usability issues and corresponding redesign solutions to enhance the usability of ACT SMARTS for use in middle and high schools.Conclusions

Results indicated the utility of CWIS in assessing implementation strategy usability in service of informing strategy modification as part of our broader redesign to improve alignment with end user, end recipient, and setting needs. Recommendations regarding the use of this participatory approach are discussed.Free full text

Applying the Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies methodology to inform the redesign of a selection-quality implementation toolkit for use in schools

Abstract

Background

Implementation strategies are key to enhancing the translation of new innovations but there is a need to systematically design and tailor strategies to match the targeted implementation context and address determinants. There are increasing methods to inform the development and tailoring of implementation strategies to maximize their usability, feasibility, and appropriateness in new settings such as the Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies (CWIS) approach. The aim of the current project is to apply the CWIS approach to inform the redesign of a multifaceted selection-quality implementation toolkit entitled Adoption of Curricular supports Toolkit: Systematic Measurement of Appropriateness and Readiness for Translation in Schools (ACT SMARTS) for use in middle and high schools.

Methods

We systematically applied CWIS as the second part of a community-partnered iterative redesign of ACT SMARTS for schools to evaluate the usability and inform further toolkit redesign areas. We conducted three CWIS user testing sessions with key end users of school district administrators (n =

= 3), school principals (n

3), school principals (n =

= 6), and educators (n

6), and educators (n =

= 6).

6).

Results

Our CWIS application revealed that end users found ACT SMARTS acceptable and relevant but anticipate usability issues engaging in the ACT SMARTS process. Results informed the identification of eleven usability issues and corresponding redesign solutions to enhance the usability of ACT SMARTS for use in middle and high schools.

Conclusions

Results indicated the utility of CWIS in assessing implementation strategy usability in service of informing strategy modification as part of our broader redesign to improve alignment with end user, end recipient, and setting needs. Recommendations regarding the use of this participatory approach are discussed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s43058-024-00665-x.

Background

Implementation strategies, or methods or techniques to enhance adoption, use, and sustainment of new innovations, are critical to facilitating implementation outcomes such as feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness [1, 2]. There have been increasing efforts to develop and test implementation strategies, including discrete or singular strategies and multifaceted or two or more singular strategies [2]. Yet, variable effects of implementation strategies, particularly multifaceted strategies, are common [3–6]. The limited systematic or intentional design of implementation strategies considering the contexts in which they are deployed contributes to these limited effects, prompting increased calls and an emerging focus on more intentional, systematic development and tailoring of implementation strategies [2]. Fortunately, there have been increased efforts to develop feasible, pragmatic methods for designing and tailoring implementation strategies and a corresponding growing literature describing their application and impact (e.g., [7–9]). The Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies (CWIS) is one such method for assessing implementation strategy usability in service of informing strategy redesign [10]. Yet, additional use of this method is needed to inform further development and application, particularly in real-world practice. As such, the current work describes the application of the CWIS method as part of a broader project that aims to iteratively redesign a multifaceted selection-quality (i.e., targeting the appropriate identification and selection of an evidence-based practice (EBP) or tool) implementation toolkit for use in the novel context of middle and high schools.

Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies

CWIS is drawn from the human-centered design (HCD) field. HCD aims to develop or design products that are intuitive, effective, and match the needs and desires of its intended users and contexts [11]. Towards that goal, HCD methods frequently involve evaluating and understanding user and context-specific needs and constraints, and iterative prototyping paired with ongoing user-testing to inform the development of appropriate, usable products [12, 13]. A primary goal and outcome of HCD is usability or the extent to which a product can be used by specified individuals to achieve specified goals in a specified context [14]. While related to other implementation outcomes such as acceptability and feasibility relevant within implementation studies, usability is conceptualized as a determinant predictive of implementation outcomes [10]. Although other approaches may be recommended when the primary goal centers around evaluating fit or feasibility (e.g., Implementation Mapping; [7]) or documenting the adaptation process itself (e.g., the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Implementation Strategies or FRAME-IS; [15]), CWIS is particularly suitable and effective in identifying and addressing potential usability issues through its specific emphasis on usability as its primary outcome in service of redesign.

Consistent with HCD, CWIS is designed to be a low cost, pragmatic method to evaluate implementation strategy usability and has been applied to complex or multifaceted strategies. CWIS specifies six sequential tasks or steps. The first step of CWIS (Step 1) involves determining preconditions or the necessary situations or prerequisites required for an implementation strategy to be effective. Users then complete a hierarchical task analysis (Step 2) whereby tasks or steps comprised within the implementation strategy are articulated and specified. This task includes identifying the behavioral or cognitive activities prescribed within the strategy as well as specifying the sequence of tasks required to enact or carry out the implementation strategy. Next, task prioritization (Step 3) occurs whereby tasks that 1) are most important to be completed correctly or 2) where users are most likely to encounter issues or commit errors that impede the execution or success of the implementation strategy are identified and prioritized. Specifically, tasks identified in prior steps are rated on these two dimensions of likelihood of success by those with strategy expertise or strong familiarity. Mean ratings are calculated to combine likelihood of issue/error and completion importance. The highest rated tasks are then selected and prioritized. While there are no task selection cutoffs articulated for the CWIS method, raters make the final task selections based on those identified as highest importance.

The fourth step (Step 4) involves converting the prioritized tasks into a series of scenarios and subtasks which are used for pragmatic user testing (Step 5) with a sample of representative end users. During testing sessions, user testing participants are presented with the developed scenarios and tasks and asked to cognitively enact and reflect on presented tasks. Participants then complete quantitative ratings of their anticipated likelihood of success and provide corresponding qualitative justifications for ratings. Following user testing, the last step (Step 6) involves usability issue identification, prioritization, and classification, which points to key areas for implementation strategy redesign. Since its inception, there is increasing incorporation of CWIS into new proposals and projects (e.g., [16–18]) but published work detailing its application remain limited, particularly independent applications outside of method developers. Further application and examples of CWIS completed independently from its developers, particularly those validating and identifying areas for further refinement to ensure its successful, independent application, are needed to inform and develop this novel method and enhance its potential to advance its impact on the field.

Current aims

The current work provides a case study of the application of CWIS to identify key usability issues to inform further redesign of a multiphase and multi-activity selection-quality implementation toolkit entitled Adoption of Curricular supports Toolkit: Systematic Measurement of Appropriateness and Readiness for Translation in Schools (ACT SMARTS; described below) for use in middle and high schools within the context of autism EBP implementation. Specific guiding research questions as part of the CWIS application include:

To what extent does the CWIS methodology highlight end users’ understanding of the ACT SMARTS phases and activities presented to them?

To what extent does CWIS support identification of usability issues users encounter when attempting to complete ACT SMARTS activities and tasks?

To what extent does the CWIS methodology support identification of which ACT SMARTS activities are most problematic or difficult for users to complete?

To what extent does the CWIS methodology inform further redesign of ACT SMARTS components to maximize usability and fit in schools?

Methodology and case study application

Case study application context and guiding frameworks

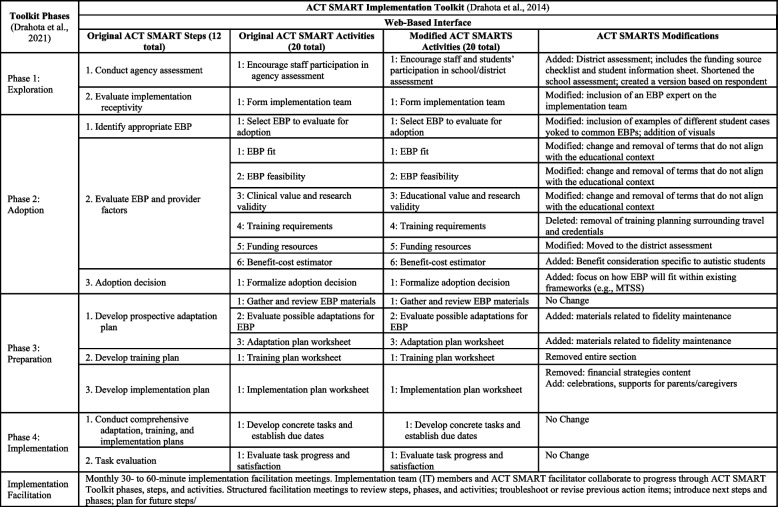

We applied the CWIS approach to create the redesigned ACT SMARTS for use in middle and high schools. Originally developed in collaboration with a community-academic partnership for use in community-based autism-focused organizations, preliminary data support the feasibility, acceptability, utility, and effectiveness of ACT SMARTS in such settings [19, 20]. However, redesign was needed to enhance its fit and utility in public schools given the unique implementation context of schools and importance of context-specific fit [21, 22] and well documented need to design and tailor implementation strategies to ensure they are well-matched for their deployment contexts [2]. The goal of this project was to use the novel CWIS methodology as part of the iterative, systematic redesign of this original toolkit to create ACT SMARTS. We elected to apply the CWIS methodology because to our knowledge, it is one of the only documented methods for user testing of implementation strategies. Two frameworks guided this broader project. First, the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS; [23, 24]) framework is the overarching guiding framework given its application during the development of and integration in the original toolkit. In particular, we applied the adapted EPIS framework utilized in prior work focused on this toolkit which specified an additional adoption decision phase following the Exploration phase [25]. In our application, we elected to not focus on the Sustainment phase as data suggest that full implementation in schools can take 3–5 years [26] and even then, successful implementation is challenging let alone sustained implementation (e.g., an implementation cliff following summer break) [27]. Given this and the time limited nature of our project, we prioritized our focus on the Exploration, Preparation, and Implementation phases. Additionally, we apply the Discover, Design, Build, and Test (DDBT; [28]) framework to guide the iterative redesign process. The initial redesign methods, procedures, and full description of redesigned ACT SMARTS prototype are described in Locke et al. [28]. In brief, we engaged community members (i.e., educators, administrators, autistic individuals, caregivers of autistic youth) in mixed-method data collection sessions consisting of focus groups and survey collection to identify perceptions and necessary areas for redesign of the original toolkit to optimize its feasibility and utility in middle and high schools. Results informed the iterative redesign and development of a modification blueprint of ACT SMARTS (See Fig. Fig.11).

Adoption of Curricular supports Toolkit: Systematic Measurement of Appropriateness and Readiness for Translation in Schools (ACT SMARTS) Intervention

ACT SMARTS is a packaged, multifaceted selection-quality implementation toolkit that strategically targets the identification and selection of appropriate autism EBPs [28]. ACT SMARTS includes a school-based implementation team comprised of principals or other leaders and educators involved in EBP selection, phase-specific activities, and facilitation. It has four implementation phases with corresponding steps and activities: 1) Exploration: a district, school, and autistic student needs assessment evaluating organizational determinants (e.g., implementation climate, organizational readiness) and student and professional needs. 2) Adoption: activities to support the identification and evaluation (e.g., feasibility, fit) of relevant EBPs that match needs and determinants identified in Phase 1. This phase culminates with a formal EBP adoption decision made by the school-based implementation team. 3) Preparation: activities and tools to guide planning for EBP adaptation, staff training, and EBP implementation. 4) Implementation: EBP implementation, guided by products developed during the prior preparation phase such as the adaptation and implementation plan, and an evaluation of implementation efforts. The ACT SMARTS implementation facilitator systematically supports the school-based implementation team as they carry out the ACT SMARTS phase-specific activities and tasks. The current work represents the next step in this multiphase project where we subjected the redesigned ACT SMARTS prototype to further user testing to evaluate its usability and inform further refinements prior to conducting a feasibility pilot test in middle and high schools.

Procedures: Application of the CWIS methodology

Step 1: Determine preconditions of the implementation strategy

Consistent with the first step of CWIS, four members, including study PIs with expertise in EBP implementation in schools, the original developer of the implementation toolkit and a graduate student with expertise in the implementation toolkit, collectively determined preconditions at both the individual, school, and district levels. Individual or educator level preconditions included those involved in the selection and/or delivery of autism EBPs in their school and access to resources as EBP supports (e.g., training or education, funding). School preconditions similarly included leaders involved in the selection of autism EBPs in their schools and access to resources as EBP supports. District preconditions included administrators involved in the selection of autism EBPs and identifying or allocating resources as EBP supports.

Step 2: Hierarchical task analysis

We then conducted a hierarchical task analysis by identifying all tasks and subtasks that comprised ACT SMARTS’ four phases (i.e., Exploration, Adoption, Preparation, Implementation). Four members of the study team, including the PIs, the original developer of the toolkit, and an additional doctoral level graduate student with expertise with the original implementation toolkit, participated in this step. We identified corresponding user groups, with some tasks unique to one end user group (e.g., the funding checklist only relevant to principals or other leaders) and others relevant tasks across user groups. We then articulated, reviewed, and revised specified tasks to generate a complete list of tasks associated with completion of the ACT SMARTS process.

Step 3: Task prioritization

As part of task prioritization, we prioritized the specific ACT SMARTS tasks to include in subsequent user testing sessions, including reviewing and rating the potential tasks on the anticipated likelihood of an issue or committing an error and importance of completing a task correctly. After combining ratings, the highest rated tasks were selected and prioritized for user testing based on completion importance followed by likelihood of issue/error. We selected 9 tasks for conversion to scenarios and subtasks, with 6 subtasks chosen for district administrators, 9 subtasks for school principals, and 8 subtasks for educators.

Task 4: Convert top tasks to testing scenarios

We converted selected tasks to scenarios and subtasks (Step 4) for each user type (i.e., district administrator, school administrator, educator). Consistent with CWIS, we crafted overarching scenarios from task themes to provide background context on settings and activities to aid users in cognitively illustrating how, when, where, and with whom its subtasks were to occur during user testing. Subtasks within scenarios were created around related prioritized tasks. We revised tasks through an iterative process to ensure that scenarios will be independent of one another and that subtasks will be discrete, achieved through the expansion, combination, and operationalization of prioritized tasks. To exemplify, our team iteratively revised the tasks associated with Scenario 1 regarding the completion of the District Assessment to ensure at a minimum that each task probed for a specific, unique aspect associated of this activity. As a result, we included three separate tasks to evaluate the ability to complete the activity within an administrator’s workday (Task 1), nominating fellow administrators to also complete the task (Task 2), and successful completion of the questions within the assessment (Task 3). See Table 1 for full listing of scenarios and subtasks.

Table 1

ACT SMARTS Scenarios and Tasks for User Testing Scenario and Tasks

| Scenario and tasks for district administrators | ||

ACT SMARTS Element ACT SMARTS Element | Scenario | Tasks |

District assessment District assessment | Your district is interested in using the ACT SMARTS toolkit to identify and adopt an evidence-based practice. As part of the first phase of ACT SMARTS, you are asked to complete a 20–30-min, online District Assessment survey battery identifying areas of strengths, areas for growth, and receptivity for a new program. The assessment asks about ongoing initiatives and priorities in your district, funding for new programming, and your perceptions of readiness for adopting a new program in your district | Task 1–1: You are asked to identify times in your schedule to complete the 20–30-min, online District Assessment survey battery during your workday Task 1–2: Prior to completing the District Assessment survey battery, you are asked to nominate 1–2 district administrators who can complete this 20–30-min online District Assessment battery Task 1–3: When completing the 20–30-min online District Assessment survey battery, you are able to easily reflect when answering the questions about ongoing initiatives and priorities in your district, funding for programming, and readiness for adopting a new program in your district |

Funding source checklist Funding source checklist | You are asked to complete the Funding Source Checklist as part of your District Assessment survey battery to identify funding available to support the adoption and delivery of the different evidence-based practices that schools in your district are considering using this upcoming year | Task 2–1: You are being asked to identify one (or more than one) of the different funding streams that can be accessed to pay for various evidence-based practices (e.g., academic curriculum, socio-emotional programming, behavioral interventions, etc.) at your district that can be used to support the adoption of the selected evidence-based practice to complete the Funding Source Checklist |

District assessment—Benefit and Cost Estimator District assessment—Benefit and Cost Estimator | You also are asked to complete the Benefit and Cost Estimator exploring the potential benefits and costs of program implementation as part of your 20–30-min online District Assessment survey battery to support the decision to adoption and implementation of the evidence-based practice you are considering in schools | Task 3–1: You are being asked to identify and use information related to benefits and costs (e.g., hourly wages, process for rolling out new initiatives with training, cost of training and materials, etc.) of potential evidence-based practices to complete the Benefit/Cost Estimator Task 3–2: You are asked to consider and specify the different initiatives and priorities (e.g., MTSS, PBIS, curricular piloting) that the district is currently implementing as part of completing the Benefit/Cost estimator, including how funding and adopting a new evidence-based practice fits within and/or complements these existing programs |

| Scenario and tasks for principals | ||

ACT SMARTS element ACT SMARTS element | Scenario | Tasks |

School assessment School assessment | Your district as well as your school are interested in using the ACT SMARTS toolkit to identify and adopt an evidence-based practice. As part of the first phase of ACT SMARTS, you are asked to complete a 20–30-min, online School Assessment survey battery to identify areas of strengths, areas for growth, and receptivity for a new program at your school. The assessment asks about ongoing initiatives and priorities, funding for new programming, and your perceptions of readiness for adopting a new program in your school or district. As part of this process, you also are asked to nominate additional educators and staff at your school to complete this 20–30-min, online School Assessment survey | Task 1–1: You are asked to identified times in your schedule to complete the 20–30-min online School Assessment survey battery during your workday Task 1–2: You are asked to identify and nominate 3–5 educators who have the knowledge to complete the 20–30-min online School Assessment survey battery Task 1–3: When completing the 20–30-min online School Assessment survey battery, you are able to easily reflect when answering the questions about ongoing initiatives and priorities, funding for programming, and readiness for adopting a new program in your school or district |

Benefit and cost estimator Benefit and cost estimator | You are asked to complete the Benefit and Cost Estimator as part of your 20–30-min online School Assessment survey battery exploring the potential benefits and costs of program implementation to support the decision to adopt and implement at the evidence-based practice that you are considering in your school | Task 2–1: You are being asked to identify and use information related to benefits and costs (e.g., hourly wages, cost of training and materials, etc.) of potential evidence-based practices to complete the Benefit/Cost Estimator Task 2–2: You are asked to consider and specify the different initiatives and priorities (e.g., MTSS, PBIS, curricular piloting) that the district is currently implementing to complete the Benefit and Cost Estimator. You understand how funding and adopting a new evidence-based practice fits within and/or complements these existing programs Task 2–3: You are being asked to identify one or more of the different evidence-based practice (e.g., academic curriculum, socio-emotional programming, behavioral interventions, etc.) funding streams at your school or district that can be used to support the adoption and implementation of the selected evidence-based practice to complete the Funding Source Checklist |

Feedback report Feedback report | Following the completion of the School Assessment within your school, you are provided with School Assessment Feedback report providing summative, aggregate feedback from the school assessment completed by yourself and other staff at your school. You are asked to review a summative feedback report of your aggregated School Assessment survey data and use this report to complete Phase 1 of the ACT SMARTS Process, developing and assembling your school's implementation team, and move into Phase 2 where you will begin to identify and assess an evidence-based practice for adoption | Task 3–1: Following review of the School Assessment Feedback Report, you are able to interpret and make sense of the results to inform the identification and potential adoption of an evidence-based practice at your school with an ACT SMARTER Facilitator Task 3–2: Following review of the School Assessment Feedback Report, you are asked to identify areas of strength and areas where your school may need support in order to implement a new evidence-based practice |

Implementation plan Implementation plan | You have decided to select Reinforcement as your evidence-based practice in Phase 2. During a Facilitation meeting with an ACT SMARTS Facilitator, you are asked to draft your own Implementation Plan that your school implementation team will use to guide your implementation of Reinforcement | Task 4–1: You are asked to identify areas to work on and use the Implementation Plan to develop goals to support the immediate implementation of your selected evidence-based practice, Reinforcement Task 4–2: You are asked to identify areas to work on and use the Implementation Plan to develop goals to support the sustainment and ongoing use of your selected evidence-based practice, Reinforcement Task 4–3: You are asked to execute the Implementation Plan to monitor and evaluate goal progress related to the implementation of your selected evidence-based practice, Reinforcement, over the course of the school year |

| Scenario and tasks for educators | ||

ACT SMARTS element ACT SMARTS element | Scenario | Tasks |

School assessment School assessment | Your district as well as your school are interested in using the ACT SMARTS toolkit to identify and adopt an evidence-based practice. As part of the first phase of ACT SMARTS, you are asked to complete a 30-min, online School Assessment survey battery to identify areas of strengths, areas for growth, and receptivity for a new program at your school. The assessment asks about ongoing initiatives and priorities, funding for new programming, and your perceptions of readiness for adopting a new program in your school or district. As part of this process, you also are asked to nominate additional educators and staff at your school to complete this 20–30-min, online School Assessment survey | Task 1–1: You are asked to identified times in your schedule to complete the 30-min online School Assessment survey battery during your workday Task 1–2: You are asked to identify and nominate 3–5 educators who have the knowledge to complete the 30-min, online School Assessment survey battery Task 1–3: When completing the 30-min online School Assessment survey battery, you are able to easily reflect when answering the questions about ongoing initiatives and priorities, funding for programming, and readiness for adopting a new program in your school or district |

Implementation plan Implementation plan | You have decided to select Unstuck and On Target as your evidence-based practice in Phase 2. During a Facilitation meeting with an ACT SMARTS Facilitator, you are asked to draft your own Implementation Plan that your school implementation team will use to guide your implementation of Unstuck and On Target, an intervention that addresses executive functioning (e.g., planning, organization, flexibility) | Task 2–1: You are asked to identify areas to work on and use the Implementation Plan to develop goals to support the immediate implementation of your selected evidence-based practice, Unstuck and On Target Task 2–2: You are asked to identify areas to work on and use the Implementation Plan to develop goals to support the sustainment and ongoing use of your selected evidence-based practice, Unstuck and On Target Task 2–3: You are asked to execute the Implementation Plan to monitor and evaluate goal progress related to the implementation of your selected evidence-based practice, Unstuck and On Target, over the course of the school year |

Adaptation plan Adaptation plan | You have decided to select Unstuck and On Target, an intervention that addresses executive functioning (e.g., planning, organization, flexibility), as your evidence-based practice in Phase 2. During a Facilitation meeting with an ACT SMARTS Facilitator, you are asked to draft your own Adaptation Plan that will help you and your school implementation team to determine ways in which to modify your selected evidence-based practice for use in your school prior to active implementation | Task 3–1: You are asked to identify components of your selected evidence-based practice to adapt or modify on the Adaptation Plan prior to active implementation to ensure Unstuck and On Target fits within your school Task 3–2: You are asked to identify components of your selected evidence-based practice to adapt or modify on the Adaptation Plan prior to active implementation to ensure Unstuck and On Target addresses your students' needs |

Task 5: User testing

We then conducted group testing (Step 5) across three virtual sessions (range =

= 3–6 participants) where participants assumed the ACT SMARTS district administrator (n

3–6 participants) where participants assumed the ACT SMARTS district administrator (n =

= 3), school administrator (n

3), school administrator (n =

= 6), or educator (n

6), or educator (n =

= 6) user types. Participants were assigned to a two-hour session with an associated user type based on their availability. One week prior to their session, participants received a digital copy of ACT SMARTS materials tailored to each user type, user type’s scenarios and subtasks to review, and a disclosure form to complete. Each user testing session had facilitators, a notetaker, and a technology assistant. Project PIs assumed the role of facilitators and notetakers and the study coordinator assumed the role of technology assistant. Following a standard script, the facilitator began each session with an orientation to the project including an overview of ACT SMARTS, the user testing session, and participation expectations. The cognitive walkthrough process consisted of the presentation of a scenario and its subtasks, quantitative ratings and qualitative rationales from participants, and open-ended discussion by participants. For each subtask, a written description was visually presented on a PowerPoint along with an image that depicted the subtasks’ intent. We also provided a unique link to access the previously shared digital materials for each subtask so participants could reference during user testing sessions. We asked all participants to share their quantitative likelihood of success ratings and associated rationales for each subtask. After each participant provided their ratings and justifications, the facilitator encouraged open discussion about potential barriers and facilitators for the subtask. Following the completion of all scenarios and subtasks, the facilitator presented three open-ended questions designed to capture additional comments about potential usability issues. These included: What was your overall impression of ACT SMARTS? How does this compare to other implementation strategies or supports to promote the adoption of new programs/practices that you’ve been exposed to? Is there anything else that you would like to share about your experience today or with ACT SMARTS more generally? Lastly, participants completed the 10-item Implementation Strategy Usability scale [29]. Participants received a $200 gift card for their participation.

6) user types. Participants were assigned to a two-hour session with an associated user type based on their availability. One week prior to their session, participants received a digital copy of ACT SMARTS materials tailored to each user type, user type’s scenarios and subtasks to review, and a disclosure form to complete. Each user testing session had facilitators, a notetaker, and a technology assistant. Project PIs assumed the role of facilitators and notetakers and the study coordinator assumed the role of technology assistant. Following a standard script, the facilitator began each session with an orientation to the project including an overview of ACT SMARTS, the user testing session, and participation expectations. The cognitive walkthrough process consisted of the presentation of a scenario and its subtasks, quantitative ratings and qualitative rationales from participants, and open-ended discussion by participants. For each subtask, a written description was visually presented on a PowerPoint along with an image that depicted the subtasks’ intent. We also provided a unique link to access the previously shared digital materials for each subtask so participants could reference during user testing sessions. We asked all participants to share their quantitative likelihood of success ratings and associated rationales for each subtask. After each participant provided their ratings and justifications, the facilitator encouraged open discussion about potential barriers and facilitators for the subtask. Following the completion of all scenarios and subtasks, the facilitator presented three open-ended questions designed to capture additional comments about potential usability issues. These included: What was your overall impression of ACT SMARTS? How does this compare to other implementation strategies or supports to promote the adoption of new programs/practices that you’ve been exposed to? Is there anything else that you would like to share about your experience today or with ACT SMARTS more generally? Lastly, participants completed the 10-item Implementation Strategy Usability scale [29]. Participants received a $200 gift card for their participation.

Task 6: Usability issue identification, prioritization and classification

Results from user testing directly informed our identification, classification, and prioritization of usability issues as outlined in Step 6 of the CWIS process. Employing the guidance specified by the University of Washington ALACRITY Center [30] applied in the original description of CWIS, two members of the research team (first and second authors) specified the usability issues resulting from our group testing. This included creating brief usability statements and rating the severity, scope, complexity, and consequences. Identified usability issues directly informed subsequent modifications and further redesign of ACT SMARTS to enhance its usability.

User testing recruitment and participants

Recruitment

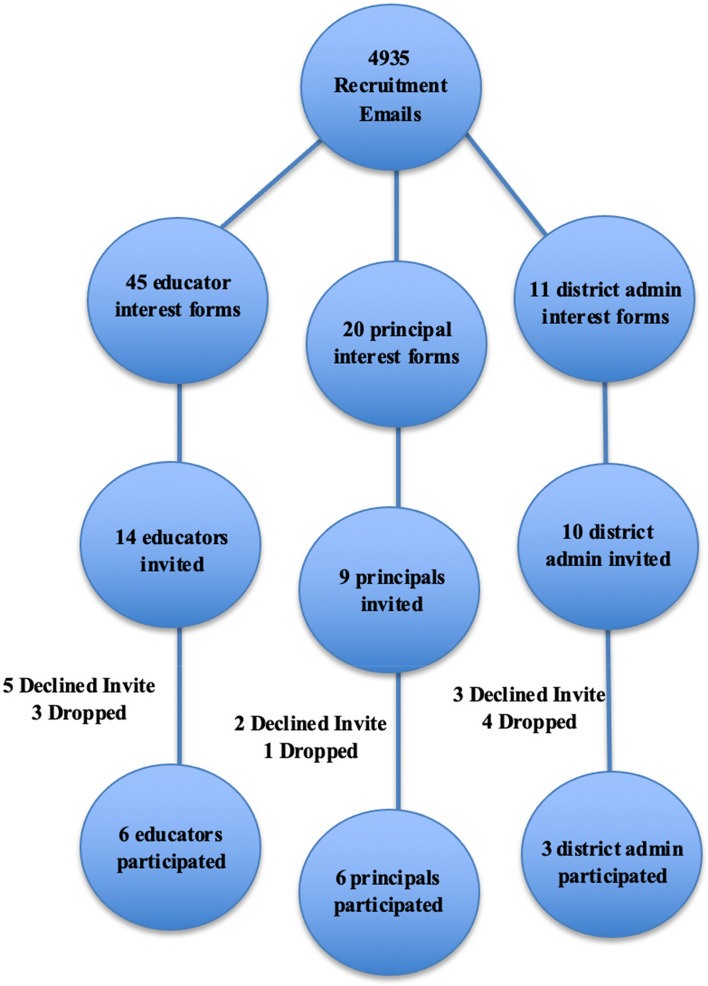

The Institutional Review Boards of San Diego State University and the University of Washington approved the study. We created a stratified recruitment plan using a free, online platform (https://www.thegeneralizer.org/; [31]), selecting specific school characteristics (e.g., School Size, % Free & Reduced Lunch, % Female, Urbanicity, % White, % Black, % Hispanic, % Two or More Races School Count, % English Language Learner, % English Only, % Other Than English) to ensure a representative sample. We categorized schools into five strata groups within California and Washington, where we conducted this study, closely mirroring the composition of the target population. We compiled a ranked list of schools based on five strata categories, including relevant corresponding school names, districts, and other demographic information. We contacted identified schools and invited them to participate, sending 4,935 recruitment emails including all study materials (e.g., flyers, IRB approvals, screener materials) to principals and educators from the strata lists; this resulted in 76 interest forms across all participants (response rate of 1.54%).

We considered various factors in participant selection, with preference given to individuals whose availability overlapped with other participants. Furthermore, participant selection considered educator role, school strata, gender, race, and ethnicity to ensure the creation of representative and diverse groups. Of the 76 interest forms received, 45 were general and special education teachers, 20 middle and high school principals, and 11 district administrators. We invited 14 general and special education teachers to participate and five of those participants either did not respond or were unavailable on the day of the CWIS session. We invited nine principals to participate and two declined due to not being available on the date of the CWIS session. We invited 10 district administrators to participate and three declined the invitation due to scheduling conflicts or did not respond. Before participation, the research team provided a full description to all participants of study procedures and activities included in study participation. For more details on recruitment and enrollment, see Fig. 2.

Recruitment and enrollment flow chart. Note. “Declined Invite” are those who were invited but did not respond to the invitation email and did not consent to participate in the group. “Dropped” are those who accepted the invitation to participate in the focus group, completed the consent, but were unable to attend the group

User testing participants

Four district administrators, three educators, and one principal were unavailable for their scheduled and confirmed CWIS session due to emergencies that came up the day of the session; all other invited participants attended their scheduled CWIS session. Participants (n =

= 15) included school district administrators (n

15) included school district administrators (n =

= 3), middle and high school principals (n

3), middle and high school principals (n =

= 6), general (n

6), general (n =

= 4) and special education (n

4) and special education (n =

= 2) teachers. Participants represented 13 school districts and 12 middle and high schools across California and Washington. Participants were primarily female (86.7%), White (73.3%) and Non-Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish Origin (73.3%), the average number of years working in a school was 19.5 years, and the average number of years working with autistic individuals was 15.9 years. The majority of educators in our study identified as White, although, this reflects the broader demographics of educators in the states where the study occurred. Educators are reported to be 93% and 63% White, respectively in these states, according to the Institute of Education Sciences [31] and the California Department of Education [32]. The diverse range of participant experiences (e.g., geographic area, age, years of experience) offered a valuable opportunity to collect insights from distinct perspectives [33]. For more detailed participant demographics, refer to Table Table22.

2) teachers. Participants represented 13 school districts and 12 middle and high schools across California and Washington. Participants were primarily female (86.7%), White (73.3%) and Non-Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish Origin (73.3%), the average number of years working in a school was 19.5 years, and the average number of years working with autistic individuals was 15.9 years. The majority of educators in our study identified as White, although, this reflects the broader demographics of educators in the states where the study occurred. Educators are reported to be 93% and 63% White, respectively in these states, according to the Institute of Education Sciences [31] and the California Department of Education [32]. The diverse range of participant experiences (e.g., geographic area, age, years of experience) offered a valuable opportunity to collect insights from distinct perspectives [33]. For more detailed participant demographics, refer to Table Table22.

Table 2

Participant demographics

| Educators | Principals | District leaders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

N = = 15 15 | 6 | 40.0 | 6 | 40.0 | 3 | 20.0 |

| Sex | ||||||

Female Female | 5 | 83.3 | 5 | 83.3 | 3 | 100 |

Male Male | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Age | ||||||

25–34 25–34 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33.3 |

35–44 35–44 | 2 | 33.3 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 |

45–54 45–54 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 |

55–64 55–64 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin | ||||||

Yes Yes | 2 | 33.3 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

No No | 4 | 66.7 | 4 | 66.7 | 3 | 100 |

| Race | ||||||

American Indian or Alaska Native American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Asian Asian | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Black or African American Black or African American | 1 | 7.1 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

Middle Eastern or North African Middle Eastern or North African | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Native Hawaiian Native Hawaiian | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

White White | 5 | 83.3 | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | 100 |

Prefer to self-describe Prefer to self-describe | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Education | ||||||

Associate degree Associate degree | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Bachelor's Degree Bachelor's Degree | 4 | 66.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Master’s Degree Master’s Degree | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 66.7 | 2 | 66.7 |

Doctoral Degree Doctoral Degree | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 |

Measures

Implementation Strategy Usability Scale (ISUS; 29)

User testing participants completed the ISUS during user testing (CWIS Step 5). The ISUS is an adapted version of the well-established System Usability Scale [34, 35], a 10-item measure of the usability of digital technologies. Odd items [1, 3, 5, 7, 9] are totaled and then five is subtracted. Even numbers [2, 4, 6, 8, 10] are totaled and then subtracted from 25 to account for reverse scoring. The two numbers are then added together and multiplied by 2.5 to obtain a final usability score. Scores range from 0–100 with <

< 50 indicating unacceptable usability and

50 indicating unacceptable usability and >

> 70 acceptable. Used in more than 500 studies, the SUS is the best-researched usability measure [35, 36].

70 acceptable. Used in more than 500 studies, the SUS is the best-researched usability measure [35, 36].

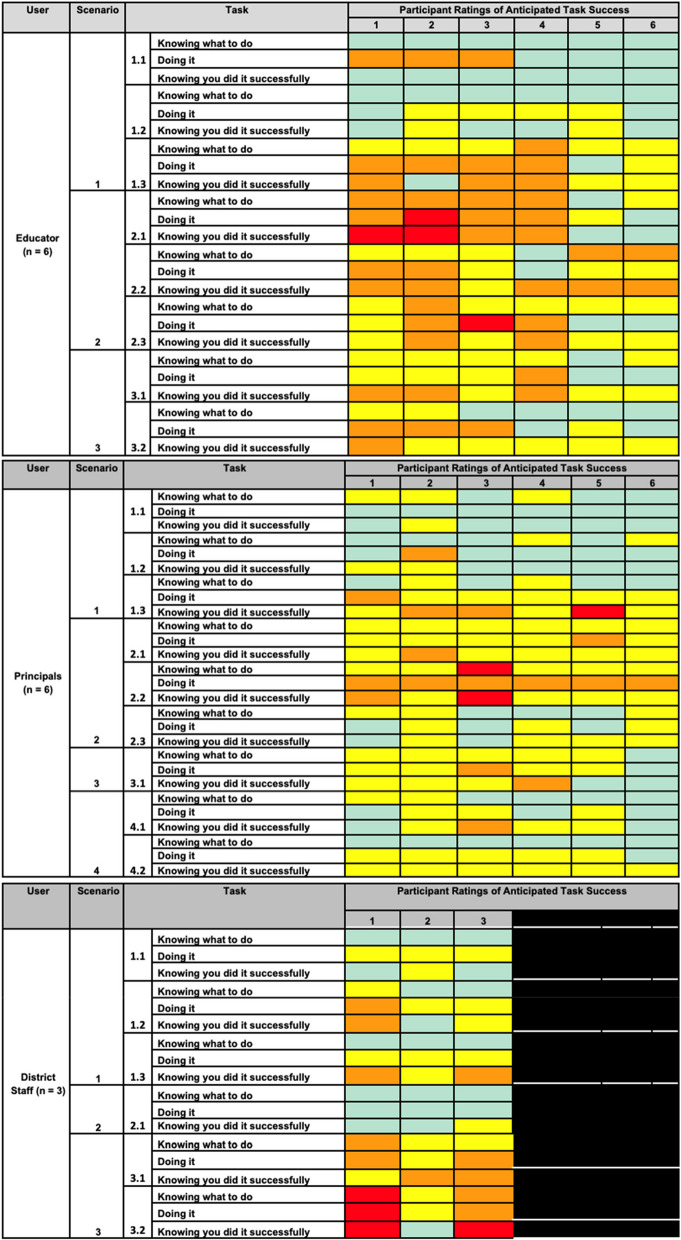

Anticipated likelihood of success

User testing participants rated the anticipated likelihood of success for each task presented (CWIS Step 5). Survey items assessed the extent to which users will be successful: [1] knowing what to do (“discovering that the correct action is an option”), [2] doing it (“performing the correct action or response”), and [3] knowing they did it successfully (“receiving sufficient feedback to understand that they have performed the correct action”). Participants rated items on a scale of “1” (No, a very small chance of success) to “4” (Yes, a very good chance of success) [10].

Analysis

Analyses focused on the mixed-methods data collected during user testing and consisted of a two-step process. First, we calculated descriptive analyses of all likelihood of success ratings, flagging ratings with ratings below a 3 (probable chance of success). We also calculated ISUS following the scoring instructions [10]. Next and consistent with the rapid qualitative assessment process [37], we identified emergent themes from our qualitative data from each participant. Rationales were transferred to templates, organized by identified tasks and subtasks, with those tasks or subtasks included across user types grouped together, and linked with quantitative ratings of success. Together, quantitative and qualitative ratings informed our identification of usability issues regarding the ACT SMARTS (Step 6). Consistent with the CWIS methodology, we developed a description of the issue and classified the corresponding severity, scope, level of complexity, and problem type to identify and sort usability issues. Qualitative themes and usability issues were reviewed and validated by a team member not involved in the coding. The resulting usability issues provided insight into the feasibility and contextual appropriateness of the ACT SMARTS prototype for each user type (i.e., district or school administrator, educator, school-based clinician). Lastly, our team collectively developed redesign solutions for the ACT SMARTS based on the usability issue descriptions and evidence provided.

Results

ACT SMARTS anticipated likelihood of success

Results from the participants’ anticipated likelihood of success ratings for each subtask, as presented during user testing, are illustrated in Fig. 3. The ratings are color-coded to visually represent the scale utilized for our likelihood of success ratings, with "1" indicating "No, a very small chance of success" (depicted in red), "2" indicating "No, probably not" (depicted in orange), "3" indicating "Yes, probably" (depicted in yellow), and "4" indicating "Yes, a very good chance of success" (depicted in green). Overall, educators indicated a higher anticipated success of knowing what to do (M =

= 3.23, SD

3.23, SD =

= 0.72) to complete ACT SMARTS tasks than doing it (M

0.72) to complete ACT SMARTS tasks than doing it (M =

= 2.83, SD

2.83, SD =

= 0.91) and knowing they did it successfully (M

0.91) and knowing they did it successfully (M =

= 2.85, SD

2.85, SD =

= 0.87). As seen in Fig. 3, there was significant variation in the ratings across subtasks, with high likelihood of completing tasks associated with scenario 1 tasks of ACT SMARTS (e.g., completing a school assessment) and lower perceived likelihood of completing scenario 2 tasks (i.e., implementation plan development). Principals indicated a higher likelihood for anticipated success than educators, with knowing what to do (M

0.87). As seen in Fig. 3, there was significant variation in the ratings across subtasks, with high likelihood of completing tasks associated with scenario 1 tasks of ACT SMARTS (e.g., completing a school assessment) and lower perceived likelihood of completing scenario 2 tasks (i.e., implementation plan development). Principals indicated a higher likelihood for anticipated success than educators, with knowing what to do (M =

= 3.33, SD

3.33, SD =

= 0.63), doing it (M

0.63), doing it (M =

= 3, SD

3, SD =

= 0.68), and knowing they did it successfully (M

0.68), and knowing they did it successfully (M =

= 3, SD

3, SD =

= 0.63) between “Yes, probably” and “Yes, a very good chance of success,” and an overall average across subtasks and factors of 3.11 (SD

0.63) between “Yes, probably” and “Yes, a very good chance of success,” and an overall average across subtasks and factors of 3.11 (SD =

= 0.66). Again, there was similar variation across the ratings with performing the action and receiving sufficient feedback to know they performed the correct action scoring slightly lower than identifying the correct action. Finally and similar to educator participants, district administrators indicated higher anticipated success knowing what to do (M

0.66). Again, there was similar variation across the ratings with performing the action and receiving sufficient feedback to know they performed the correct action scoring slightly lower than identifying the correct action. Finally and similar to educator participants, district administrators indicated higher anticipated success knowing what to do (M =

= 3.39, SD

3.39, SD =

= 0.92) to complete ACT SMARTS tasks than doing it (M

0.92) to complete ACT SMARTS tasks than doing it (M =

= 2.83, SD

2.83, SD =

= 0.79) and knowing they did it successfully (M

0.79) and knowing they did it successfully (M =

= 2.83, SD

2.83, SD =

= 1.04); ratings were generally between “Yes, probably” and “Yes,” with an overall average across subtasks and factors of 3.02 (SD

1.04); ratings were generally between “Yes, probably” and “Yes,” with an overall average across subtasks and factors of 3.02 (SD =

= 0.94). Again, there was similar variation across the ratings with performing the action and receiving sufficient feedback to know they performed the correct action scoring lower than identifying the correct action. In terms of our Research Question 1, results suggest that the application of CWIS aided in identification of users’ understanding, with users demonstrating a general, albeit variable, understanding or knowledge of what to do in terms of the ACT SMARTS activities but more limited anticipated success doing the task and knowledge they completed it successfully. Results also pointed to key tasks or activities that are more problematic for users to complete (Research Question 2), including completion of the Phase 1 school assessment, Phase 2 EBP Benefit/Cost estimator, and Phase 3 adaptation and implementation plans.

0.94). Again, there was similar variation across the ratings with performing the action and receiving sufficient feedback to know they performed the correct action scoring lower than identifying the correct action. In terms of our Research Question 1, results suggest that the application of CWIS aided in identification of users’ understanding, with users demonstrating a general, albeit variable, understanding or knowledge of what to do in terms of the ACT SMARTS activities but more limited anticipated success doing the task and knowledge they completed it successfully. Results also pointed to key tasks or activities that are more problematic for users to complete (Research Question 2), including completion of the Phase 1 school assessment, Phase 2 EBP Benefit/Cost estimator, and Phase 3 adaptation and implementation plans.

ACT SMARTS usability

In terms of Research Question 2, CWIS aided the identification of ACT SMARTS usability issues. Specifically, ISUS results indicated variable perceptions from all participants regarding the usability of the ACT SMARTS, with higher average usability ratings from educators (Mean =

= 45.83; SD

45.83; SD =

= 13.93; Range

13.93; Range =

= 42.50 – 65.00) and district administrators (Mean

42.50 – 65.00) and district administrators (Mean =

= 55.83; SD

55.83; SD =

= 15.07; Range

15.07; Range =

= 40.00 – 70.00) than principals (Mean

40.00 – 70.00) than principals (Mean =

= 52.50; SD

52.50; SD =

= 9.49; Range

9.49; Range =

= 22.50 – 62.50). According to the standards put forth by Bangor et al. (2008), the average educator user type rating was indicated to be between “poor” (1st quartile) and “ok” (2nd quartile). The average principal and district user type rating was between “ok” (1st quartile) and “good” (2nd quartile). These scores all fall into the “marginal” range. Table Table33 ISUS lists the usability ratings for ACT SMARTS.

22.50 – 62.50). According to the standards put forth by Bangor et al. (2008), the average educator user type rating was indicated to be between “poor” (1st quartile) and “ok” (2nd quartile). The average principal and district user type rating was between “ok” (1st quartile) and “good” (2nd quartile). These scores all fall into the “marginal” range. Table Table33 ISUS lists the usability ratings for ACT SMARTS.

Table 3

Implementation Strategy Usability Scale (ISUS) scores by user type

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | 6 | 22.5 | 62.5 | 52.5 | 9.49 |

| Educator | 6 | 42.5 | 65 | 45.83 | 13.93 |

| Admin | 3 | 40.0 | 70.0 | 55.83 | 15.07 |

ACT SMARTS usability problems and redesign solutions

Pertaining to Research Question 3, results from our CWIS user testing greatly informed the identification of 11 key usability issues of ACT SMARTS. Many issues were identified across user types (e.g., limited knowledge and experience impeding educator and principal development and use of the implementation plan, limited appropriate staff making principals and district administrators unable to nominate enough staff to complete the school assessment). Across all ACT SMARTS phases and tasks, we identified usability issues involving the following: 1) limited knowledge or experience and/or alignment with their professional role; 2) competing professional demands and/or limited compelling rationale for completion; 3) the need to involve others or gather additional information; 4) not having enough relevant staff to nominate for the school or district assessment; 5) volume of information and/or amount of effort required; 6) challenges interpreting results to inform EBP selection and decision making; and 7) challenges identifying EBP benefits prior to its selection. Usability issues ranged from low-medium in complexity (“solutions are clear and feasible” to “solutions are somewhat unclear”) and all but one had severity ratings that ranged from “creates significant delay and frustration” to “has a minor effect on usability.” Our usability issue regarding challenges identifying the benefits of an EBP prior to its selection had a higher severity rating of “prevents completion of a task.” Consistent with CWIS, usability issues informed the identification and subsequent execution of redesign solutions to enhance the usability of the ACT SMARTS in schools (Research Question 4). We identified redesign solutions for each usability issue and included: 1) embed ACT SMARTS activities into existing school structures (e.g., meetings, professional development); 2) integrate engagement strategies to promote buy-in and completion of tasks; 3) emphasize completion of ACT SMARTS tasks during facilitation meetings to ensure appropriate knowledge and expertise and efficient completion; 4) simplify task requirements; 5) proactively notify end users of task requirements to ensure gathering of materials and/or expertise prior to completion; and 6) adjust the sequence of ACT SMARTS tasks to ensure successful completion. See Table 4 for full listing of usability issues and corresponding ratings and redesign solutions.

Table 4

Prioritized redesign solutions

| Severity | Complexity | Scope | Phase | Usability issue | Redesign solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Medium | 3 | 1 | When asked to complete the school assessment, the educators reported competing professional demands limiting ability to identify a 30-min window to complete the assessment, leading to uncertainty about whether they could complete the school assessment during their workday | Embed the school assessment requirements into the structures of the school team (such as staff meetings, professional development days, prep time, etc.) |

| 2 | Medium | 3 | 1 | When asked to complete the school assessment, the educators reported limited compelling rationale for collecting these data limiting ability to identify a 30-min window to complete the assessment, leading to uncertainty about whether they could complete the school assessment during their workday | Integrate additional rationale and engagement strategies into the distribution of the school assessment to improve educator and leader buy-in to aid assessment completion |

| 2 | Medium | 8 | 1 | When asked to reflect on ongoing initiatives and priorities, funding for programming, and readiness for adopting a new program in their school, educators and principals identified having a limited scope of knowledge and little control related to ongoing initiatives, priorities, and funding leading to difficulty in reporting on these topics when completing the school assessment | Further tailoring of Phase 1 assessments to align with user group, including retaining funding questions for the district, but not school, assessment |

| 3 | Low | 2 | 1 | When asked to identify and nominate 3–5 educators and admin who have the knowledge to complete the 30-min online school assessment, principals and admin reported not having enough relevant educators or staff to nominate to complete the survey, resulting in inability to reach required response rate for this component | Decreased number of nominations required to complete this task |

| 2 | Medium | 8 | 1 | When asked how the EBP fits within and/or complements these existing programs, principals noted that the large number of initiatives and the need to coordinate with others to complete would impede the evaluation of new program fit making it difficult to appropriately complete this step of the toolkit | Proactively notify end users of the information requested so they can gather necessary materials or information prior to completion |

| 3 | Low | 2 | 1 | When asked to use the feedback report to identify an EBP to implement at the school, principals struggled to interpret the results to inform EBP selection, resulting in difficulties in making a final decision about an EBP to explore for potential selection | Emphasize the task of interpretation of the feedback report to inform the selection of an EBP as part of the ACT SMARTS facilitation process |

| 2 | Medium | 2 | 2 | When asked to identify and use information to complete the Benefit/Cost Estimator, principals identified issues in identifying sources or contacts to gather needed information, resulting in difficulties appropriately completing the Benefit/Cost Estimator | Proactively notify end users of the information requested so they can gather necessary materials or information prior to completion |

| 1 | Low | 3 | 2 | When asked to identify and use information to complete the Benefit/Cost Estimator, district administrators struggled to identify benefits of EBPs before implementation/not having the selected EBP in mind, resulting in inaccurate or incomplete responses on the Benefit/Cost Estimator | Adjust the sequencing of ACT SMARTS activities so this activity occurs after an EBP is selected |

| 2 | Medium | 6 | 3 | When asked to develop and use the implementation plan to support the immediate EBP roll out, educators and principals stated limited experience, knowledge, and alignment with their professional role, leading to difficulties developing and using the implementation plan | Emphasize completion of implementation plan with the implementation team during an ACT SMARTS facilitated session to ensure distributed and appropriate expertise and knowledge |

| 2 | Medium | 5 | 3 | When asked to use the implementation plan to support EBP use and sustainment, educators reported the volume of information and level of experience required as challenging to complete on their own, resulting in difficulties using the implementation plan to support the sustainment and ongoing use of the EBP | Simplify and reduce volume of information included in the implementation plan to aid successful completion |

| 3 | Low | 3 | 3 | When asked to identify components of the selected EBP to adapt or modify on the adaptation plan, educators indicated that the number of adaptations common during EBP use presents a barrier for completing the adaptation plan, which led to uncertainty about the feasibility of completing the adaptation plan | Adjust guidance provided for the adaptation plan and emphasize completion of adaptation plan with the implementation team during an ACT SMARTS facilitated session to aid in efficient and effective completion |

Some redesign solutions might address multiple issues. Conversely, there may be some usability issues that cannot be fully addressed

Discussion

Here we present a case study applying the CWIS methodology [10] to identify key usability issues in service of informing further redesign of ACT SMARTS, a multifaceted selection-quality implementation toolkit, for its use in middle and high schools. Our results confirmed that our CWIS application highlighted users’ understanding of ACT SMARTS activities and tasks (Research Question 1) and specific usability issues in completing tasks (Research Question 2). Additionally, CWIS greatly aided in the identification and articulation of key user issues for specific ACT SMARTS activities that were problematic and/or challenging to complete (Research Question 3) as well as corresponding redesign solutions to enhance its potential usability in schools (Research Question 4). Overall, our findings highlight the potential to use this methodology to inform the design and development of implementation strategies to enhance their effectiveness in key community settings such as schools.

As mentioned, CWIS demonstrated significant utility in not only the identification but also the articulation of the specific usability issues associated with the ACT SMARTS prototype, particularly those that likely contributed to discontinued use of ACT SMARTS if not addressed. For example, users identified significant challenges completing our EBP benefit/cost estimator prior to the selection of a specific EBP during the ACT SMARTS process. Challenges completing this task prior to the selection of an EBP also emerged in previous work evaluating the original selection-quality implementation toolkit, where fidelity or adherence to and completion of this particular task was lower compared to other specified activities and tasks [19]. The identification of this usability issue informed the development and execution of a redesign solution adjusting the order or sequencing of this ACT SMARTS activity, so an EBP is selected prior to the completion of the benefit/cost estimator. There is an identified need to intentionally design and tailor implementation strategies to enhance their impact [2], and our results point to CWIS being an effective and valuable method to inform the development and modification of implementation strategies tailored for specific deployment contexts. The identification of usability issues and corresponding redesign solutions ultimately enhances the utility and potential impact of ACT SMARTS.

Results from our user testing indicated variable but overall marginal usability ratings, consistent with our prior initial redesign work that informed the development of our ACT SMARTS prototype noting strong appropriateness and acceptability but more moderate feasibility and usability [28]. These ratings are, however, lower than those observed in prior similar work applying CWIS [10, 17]. The lower usability ratings may be due to the multifaceted, multilevel, and comprehensive nature of ACT SMARTS compared to implementation strategies of focus in prior CWIS work that consists of less comprehensive multifaceted implementation strategies with fewer components and/or associated activities. Given the importance of strategic and systematic inclusion of strategies matched to specific contexts and determinants [2], our usability results prompted evaluation of the need for the full spectrum of tasks and activities detailed in ACT SMARTS. Importantly, our current work as well as prior redesign work support the value and need for the comprehensive nature of ACT SMARTS. However, further redesign to enhance its usability is needed. Specifically, our user testing results indicated that participants perceived ACT SMARTS activities or tasks as necessary or helpful for EBP implementation, but many tasks are novel and/or outside their expertise or experience in ways that led to challenges in completion. Again, CWIS demonstrated utility in both identifying this as a usability challenge and informing our development of a redesign solution of shifting the completion of these ACT SMARTS tasks to occur within the context of the implementation team and/or facilitation to ensure effective and successful completion.

In terms of our process applying CWIS and as can be seen in Table Table5,5, we observed key learnings from our application of the CWIS process. In addition to the numerous key learnings emerging from the user testing, we also noted the value of additional steps in enhancing the usability of ACT SMARTS. For example, completion of the Hierarchical Task Analysis (Step 2) and Task Prioritization (Step 3) tasks enabled further evaluation and identification of areas for further clarity and potential user issues that, while not significant enough to subject to user testing, could be addressed by our team to enhance ACT SMARTS usability. Our application of CWIS also underscored the value of simultaneous application of this method with other implementation science frameworks or methods. In particular, we applied CWIS as part of a broader project applying the adapted EPIS and the DDBT framework, with this methodology informing a phase of this DDBT-informed redesign process for this EPIS-informed toolkit. Beyond this, there is the potential value of applying additional frameworks such as the FRAME-IS [15] to document the accompanying adaptation or modification process. Indeed, such application would greatly aid in further specification of the redesign and modification process, which is needed to inform the science in this area [38].

Table 5

Key learnings associated with the CWIS process and corresponding steps

| CWIS Step | Key learnings resulting from step engagement |

|---|---|

| Step 1. Determine preconditions of implementation strategy | Informed understanding and development of requirements or “asks” for engaging in the ACT SMARTS process |

| Step 2. Hierarchical task analysis | Aided in thorough task analysis to ensure articulation of every step in each task to enhance efficiency and clarity |

| Step 3. Task prioritization | Aided in identification of potential end user issues or challenges to be addressed via user testing and/or by intervention developers prior to deployment |

| Step 4. Convert top tasks to testing scenarios | Prioritization of tasks most likely to need redesign |

| Step 5. User testing | Identification and elucidation of usability issues |

| Step 6. Usability issue identification, prioritization, and classification | Further clarification of usability issues and identification of corresponding redesign solution to enhance the usability of ACT SMARTS |

Several considerations and/or supports were critical to our successfully completing the prescribed, connected steps detailed as part of the CWIS process. Although this is an independent application of CWIS to a project not directly led by any of the CWIS creators, we received training and consultation from its developers which was key to our application. We received guidance in the comprehensive development of necessary preconditions and hierarchical task analysis. Most notably, we sought additional consultation regarding the development of effective, appropriate tasks and testing scenarios to optimize our user testing and in the identification and classification of usability issues. For usability classification, we particularly struggled with the classification of usability issues and specific problem types as those currently specified in CWIS did not fully capture or articulate those encountered in our application that ultimately required additional consultation from CWIS developers. Finally, we observed that user testing participants were appropriately engaged in our user testing sessions but initially experienced challenges engaging in the cognitive walkthrough. However, and per recommendations from the CWIS developers, we had participants complete an initial unrelated scenario and associated tasks to orient them to the walkthrough process. Ultimately, this example scenario was essential to ensuring all participants fully understood and appropriately engaged in subsequent walkthroughs. Together, this points to some additional considerations, resources, and areas for further development of specification within the CWIS methodology to ensure it can be successfully applied without the need for ongoing support or involvement of the CWIS developers, thereby enhancing its reach and potential impact on the field.

The application of CWIS to our ACT SMARTS prototype resulted in identification of several key usability issues and corresponding redesign solutions to enhance its utility and impact when used in middle and high schools. Following completion of this process, we integrated our developed redesign solutions into our ACT SMARTS prototype in preparation for a subsequent pilot feasibility test further examining the implementation and clinical effectiveness of this redesigned toolkit when used in middle and high schools. This pilot test is currently underway in several schools throughout California and Washington.

Limitations

We noted some limitations to the CWIS process. In addition to requiring additional support from the method developers to aid our application, we noted that the application of CWIS was a time intensive process, with the application spanning many months, similar to other projects [16]. Although this limitation certainly doesn’t outweigh the immense benefits resulting from this method, this may preclude additional applications as part of efforts that may benefit but lack the resources to engage in the CWIS process. Specific to this study and as with all studies, there are several limitations that should be noted when interpreting the results. Although we employed several best-practice methods for ensuring a representative sample of schools and districts across the United States, recruitment was limited to two Western United States regions. Additionally, we had a relatively modest sample size for our user testing that, while consistent with prior applications of CWIS and the broader human-centered design field, could impact the generalizability of findings to the wider population. While the current study represents one of the first independent applications of the CWIS methodology outside of the original developers, we received training and consultation from the developers as described above which impacted our application and results from this process. Lastly, user testing was only conducted once during the larger iterative redesign of the ACT SMARTS process.

Conclusions

Implementation strategies are critical to improving the adoption, implementation and scale-up of new innovations and there is a need to systematically and intentionally design and tailor these strategies for their specific deployment context to optimize their effectiveness. As a result, there is a critical need for effective, pragmatic methods to design and tailor implementation strategies. CWIS is a promising method for assessing implementation strategy usability to inform redesign for deployment. Overall, our results highlight the immense utility of CWIS in service of yielding an enhanced, usable implementation toolkit for use in schools, with key learnings obtained from engaging in each step of the CWIS process (see Table 5).

Acknowledgements

Drs. Dickson, Drahota and Locke are fellows of the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-08).

Abbreviations

| CWIS | Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies |

| HCD | Human-Centered Design |

| ACT SMARTS | Adoption of Curricular supports Toolkit: Systematic Measurement of Appropriateness and Readiness for Translation in Schools |

| EBPs | Evidence-Based Practices |

| EPIS | Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment |

| DDBT | Discover, Design, Build, and Test |

| ISUS | Implementation Strategy Usability Scale |

Authors’ contributions

KD, OM, AD, and JL contributed to the study conception and design. KD, OM, AD, JT, AS, and JL performed data collection and material preparation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by KD, OM, and JL, and all authors had the opportunity to comment on previous versions of the manuscript, provide edits and feedback. KD, OM, AD, JT, AS, and JL read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work and time for co-authors was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21MH130793). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the view of the NIMH.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval for was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at San Diego State University (HS-2022–0050-SMT). All participants consented to participate in the current project.

Participants completed a written disclosure form and were provided a copy for their records.

All other authors declare there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Articles from Implementation Science Communications are provided here courtesy of BMC

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00665-x

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/170283537

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Applying cognitive walkthrough methodology to improve the usability of an equity-focused implementation strategy.

Implement Sci Commun, 5(1):95, 03 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39227912 | PMCID: PMC11373107

The Cognitive Walkthrough for Implementation Strategies (CWIS): a pragmatic method for assessing implementation strategy usability.

Implement Sci Commun, 2(1):78, 17 Jul 2021

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 34274027 | PMCID: PMC8285864

Leveraging human-centered design to implement modern psychological science: Return on an early investment.

Am Psychol, 75(8):1067-1079, 01 Nov 2020

Cited by: 46 articles | PMID: 33252945 | PMCID: PMC7709137

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

1,2

1,2