Abstract

Free full text

Altered Expression of Ion Channels in White Matter Lesions of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: What Do We Know About Their Function?

Abstract

Despite significant advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis (MS), knowledge about contribution of individual ion channels to axonal impairment and remyelination failure in progressive MS remains incomplete. Ion channel families play a fundamental role in maintaining white matter (WM) integrity and in regulating WM activities in axons, interstitial neurons, glia, and vascular cells. Recently, transcriptomic studies have considerably increased insight into the gene expression changes that occur in diverse WM lesions and the gene expression fingerprint of specific WM cells associated with secondary progressive MS. Here, we review the ion channel genes encoding K+, Ca2+, Na+, and Cl− channels; ryanodine receptors; TRP channels; and others that are significantly and uniquely dysregulated in active, chronic active, inactive, remyelinating WM lesions, and normal-appearing WM of secondary progressive MS brain, based on recently published bulk and single-nuclei RNA-sequencing datasets. We discuss the current state of knowledge about the corresponding ion channels and their implication in the MS brain or in experimental models of MS. This comprehensive review suggests that the intense upregulation of voltage-gated Na+ channel genes in WM lesions with ongoing tissue damage may reflect the imbalance of Na+ homeostasis that is observed in progressive MS brain, while the upregulation of a large number of voltage-gated K+ channel genes may be linked to a protective response to limit neuronal excitability. In addition, the altered chloride homeostasis, revealed by the significant downregulation of voltage-gated Cl− channels in MS lesions, may contribute to an altered inhibitory neurotransmission and increased excitability.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) affecting more than 2 million people worldwide. MS lesions in CNS white matter (WM) are multiple focal areas of myelin loss accompanied by inflammation, gliosis, phagocytic activity, and axonal damage (Compston and Coles, 2008; Kuhlmann et al., 2017; Filippi et al., 2018; Rommer et al., 2019). Available MS therapies have little benefit for secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) patients, who develop progressive disability after a disease course characterized by inflammatory attacks. Therefore, promoting neuroprotection and remyelination are important therapeutic goals to prevent irreversible neurological deficits and permanent disability.

Ion channels play a fundamental role in maintaining WM integrity and regulating function of axons, interstitial neurons (Sedmak and Judas, 2021), glia, and vascular cells. Dysregulation of ionic homeostasis in the WM during demyelination is decisive for axonal damage and cell death and may interfere with tissue repair processes (Boscia et al., 2020). Furthermore, MS may involve an acquired channelopathy (Waxman, 2001; Schattling et al., 2014). Hence, selectively targeting ion channels in WM represents an attractive strategy to overcome axonal and glial impairment and prevent disease progression.

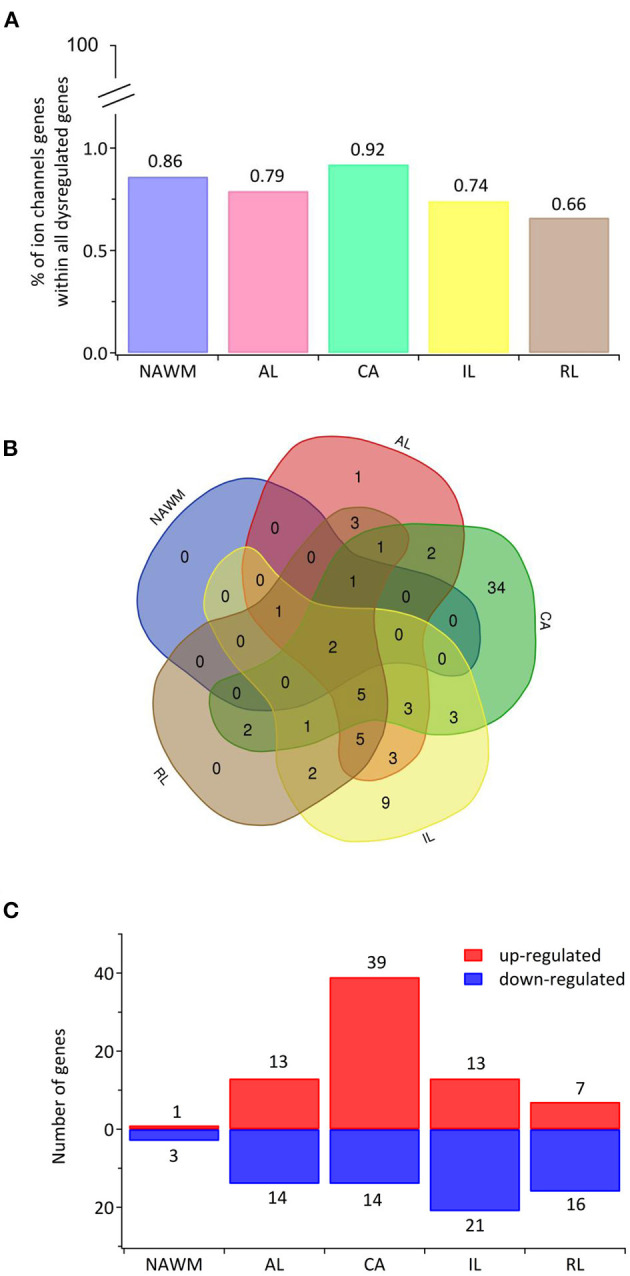

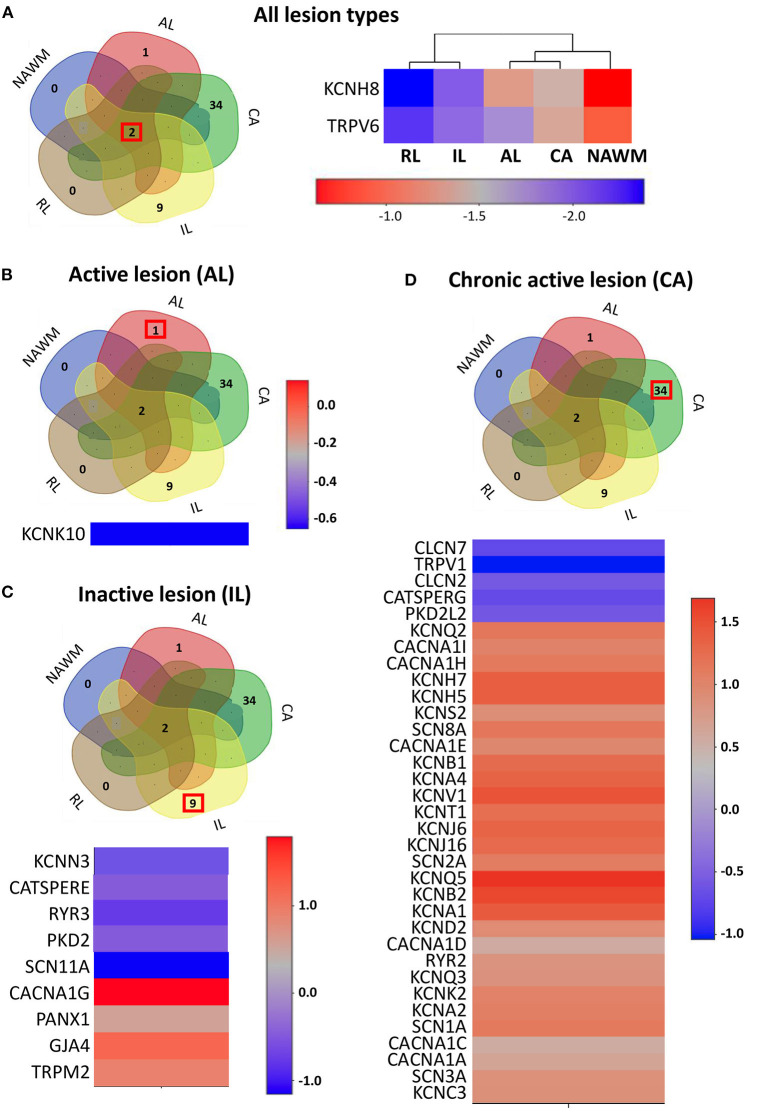

Recently, transcriptomic studies have considerably increased our insight into gene expression changes occurring in the MS brain (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Jakel et al., 2019; Schirmer et al., 2019). Aiming at identifying the ion channel genes governing WM dysfunction in SPMS brain, we analyzed the recent bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets by using the MS-Atlas (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). We put a special emphasis on the distribution of shared and unique genes encoding ion channels in chronic active (CA), active (AL), inactive (IL), and remyelinating (RL) lesions, and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) compared to control WM (Figures 1A,B, Table 1). We identified uniquely expressed ion channel genes: 34 genes in CA, 9 in IL, 1 in AL, as well as 2 genes in all lesions and NAWM (Figures 1, ,2,2, Table 1). The CA lesions displayed the highest number of upregulated ion channels genes while downregulated ion channels genes were more consistently found in ILs (Figure 1C). Next, we explored recent single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) datasets to identify the expression of dysregulated ion channel genes in cell clusters in the WM of control and SPMS brain (Jakel et al., 2019; Tables 1, ,2,2, Figure 3).

The transcriptional landscape of ion channels in different types of white matter brain lesions from patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. (A) The percentage of significantly differentially expressed genes coding for ion channels among all dysregulated genes and within each lesion type [chronic active (CA), active (AL), inactive (IL), and remyelinating (RL)] and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) compared to control white matter are indicated. (B) The Venn diagram shows the number of lesion-specific differentially expressed genes coding for ion channels and the number of overlapping genes among the lesion types. (C) The number of significantly differentially upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes in each type of while matter lesion and NAWM compared to control white matter are indicated.

Table 1

Expression and distribution of unique and overlapping genes coding for ion channels within SPMS lesions.

| Protein | Gene | Bulk lesiona | Fold change Up (+)/down (–) regulated (compared to control WM)a | Current type/conductance | Highly expressed in WM clusters of human brainb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+ channels | |||||

| Kv 1.1 | KCNA1 | CA | +1.42 | Delayed rectifier | |

| Kv 1.2 | KCNA2 | CA | +1.06 | Delayed rectifier | neuron2 |

| Kv 1.3 | KCNA3 | AL, CA, IL | +1.67 (AL); +1.35 (CA); +1.34 (IL) | Delayed rectifier | |

| Kv 1.4 | KCNA4 | CA | +1.34 | A-type | |

| Kv 1.5 | KCNA5 | AL, RL | +0.86 (AL); +1.36 (RL) | Delayed rectifier | |

| Kv 2.2 | KCNB2 | CA | +1.56 | Delayed rectifier | Neuron1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Kv 2.1 | KCNB1 | CA | +1.26 | Delayed rectifier | Neuron1, 2, 3 |

| Kv 3.3 | KCNC3 | CA | +0.87 | A-type | |

| Kv 3.4 | KCNC4 | AL, IL | +0.81 (AL); +0.72 (IL) | A-type | |

| Kv 4.2 | KCND2 | CA | +0.95 | A-type | OPC, COP, neuron1,3 |

| Kv 4.3 | KCND3 | AL, CA, IL | +0.63 (AL); +0.86 (CA); +0.93 (IL) | A-type | neuron1, 2, 3 |

| Kv 6.1 | KCNG1 | AL, RL | +2.72 (AL); +3.7 (RL) | Modifier of Kv 2 | |

| Kv 7.1 | KCNQ1 | AL, CA | +0.91 (AL); +0.75 (CA) | M-type | |

| Kv 7.2 | KCNQ2 | CA | +0.75 | M-type | neuron1, 2 |

| Kv 7.3 | KCNQ3 | CA | +0.85 | M-type | ImOLGs, neuron1, 2, 3, 5, microglia/macrophages |

| Kv 7.4 | KCNQ4 | AL, CA, IL, RL | +1.19 (AL);+ 0.92 (CA); +1.36 (IL); +2.22 (RL) | M-type | |

| Kv 7.5 | KCNQ5 | CA | +1.69 | M-type | Neuron1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Kv 8.1 | KCNV1 | CA | +1.48 | Modifier of Kv 2 | |

| Kv 9.2 | KCNS2 | CA | +0.90 | Modifier of Kv 2 | |

| Kv 9.3 | KCNS3 | AL, IL, RL, NAWM | −2.72 (AL); −1.5 (IL); −1.98 (RL); −0.71 (NAWM) | Modifier of Kv 2 | |

| Kv 10.1/EAG1 | KCNH1 | CA, IL | +0.81 (CA); +0.93 (IL) | Delayed rectifier | Neuron1, 2, 3 |

| Kv 10. 2/EAG2 | KCNH5 | CA | +1.38 | Delayed rectifier | Neuron2 |

| Kv 11.3/ERG3 | KCNH7 | CA | +1.38 | Delayed rectifier | Neuron1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Kv 12.1/ELK1 | KCNH8 | AL, CA, IL, RL, NAWM | −1.25 (AL); −1.4(CA); −2.05 (IL); −2.38 (RL); −0.62 (NAWM) | Delayed rectifier | Oligo3, Oligo4, Oligo6 |

| TREK1 | KCNK2 | CA | +1.03 | Leak, two pore | |

| TWIK2 | KCNK6 | AL, IL | +1.57 (AL); +0.82 (IL) | Leak, two pore | |

| TREK2 | KCNK10 | AL | −0.65 | Leak, two pore | |

| KCa1.1 | KCNMA1 | AL, CA, IL | +0.69 (AL); +0.87 (CA); +0.7 (IL) | Calcium-Activated | OPC, neuron1, 2, 3, 5, microglia/macrophages |

| KCa2.3 | KCNN3 | IL | −0.7 | Calcium-Activated | Astrocytes1 |

| KNa1.1 | KCNT1 | CA | +1.24 | Sodium-Activated | |

| KNa1.2 | KCNT2 | CA, IL | +0.92 (CA); +1.15 (IL) | Sodium-Activated | Neuron1, 2, 3, pericytes, vascular smooth cells |

| Kir2.1 | KCNJ2 | AL, CA, IL, RL | −0.54 (AL); −0.48 (CA); −0.54 (IL); −0.92 (RL) | Inward rectifier | |

| Kir3.4 | KCNJ5 | AL, CA, RL, NAWM | +2.58 (AL); +1.56 (CA); +1.9 (RL); +1.53 (NAWM) | Inward rectifier | |

| Kir3.2 | KCNJ6 | CA | +1.34 | Inward rectifier | Neuron1, 2, 3 |

| Kir6.1 | KCNJ8 | AL, IL | +0.74 (AL); +0.71 (IL) | Inward rectifier | |

| Kir3.3 | KCNJ9 | CA, RL | −0.52 (CA); −0.9 (RL) | Inward rectifier | |

| Kir4.1 | KCNJ10 | IL, RL | −1.06 (IL); −1.09 (RL) | Inward rectifier | Oligo5 |

| Kir5.1 | KCNJ16 | CA | +1.27 | Inward rectifier | |

| Na+ channels | |||||

| Nav1.1 | SCN1A | CA | +1.12 | TTX-sensitive | OPC, COP, neuron1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Nav1.2 | SCN2A | CA | +1.1 | TTX-sensitive | Neuron1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Nav1.3 | SCN3A | CA | +0.87 | TTX-sensitive | OPC, neuron1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Nav1.6 | SCN8A | CA | +1.15 | TTX-sensitive | Neuron1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Nav1.9 | SCN11A | IL | −1.16 | TTX-resistant | |

| Ca2+ channels | |||||

| Cav1.2 | CACNA1C | CA | +0.56 | L-type | Neuron1, 2, 3, 5, pericytes |

| Cav1.3 | CACNA1D | CA | +0.57 | L-type | Neuron1,3 |

| Cav2.1 | CACNA1A | CA | +0.64 | P/Q-type | OPC, neuron1, 2 |

| Cav2.3 | CACNA1E | CA | +0.97 | P/Q-type | Neuron1, 2, 5 |

| Cav3.1 | CACNA1G | IL | +1.8 | T-type | |

| Cav3.2 | CACNA1H | CA | +1.12 | T-type | |

| Cav3.3 | CACNA1I | CA | +1.03 | T-type | |

| Ryanodine | |||||

| Ryr2 | RYR2 | CA | +0.85 | Ca2+ Release channel | Neuron1, 2, 3 |

| Ryr3 | RYR3 | IL | −0.76 | Ca2+ Release channel | Astrocytes1 |

| TRP channels | |||||

| TRPC1 | TRPC1 | AL, IL, RL | −0.5 (AL); −0.48 (IL); −0.85 (RL) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPM2 | TRPM2 | IL | +0.92 | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPM3 | TRPM3 | IL, RL | −1.09 (IL); −0.98 (RL) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | Astrocytes1, neuron1 |

| TRPM6 | TRPM6 | CA, IL, RL | −0.99 (CA); −1.06 (IL); −1.08 (RL) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPP1 | PKD2 | IL | −0.48 | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPP3 | PKD2L2 | CA | −0.58 | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPV1 | TRPV1 | CA | −1.04 | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPV3 | TRPV3 | AL, CA, IL, RL | −0.51 (AL); −0.72 (CA); −0.5 (IL); −0.74 (RL) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPV5 | TRPV5 | AL, CA, IL, RL | −1.4 (AL); −1.67 (CA); −1.72 (IL); −2.02 (RL) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| TRPV6 | TRPV6 | AL, CA, IL, RL, NAWM | −1.77 (AL); −1.97 (IL); −1.32 (CA); −2.23 (RL); 0.86 (NAWM) | Ca2+-permeable cation channel | |

| Cl− channels | |||||

| CLC-2 | CLCN2 | CA | −0.57 | Inward rectification | |

| CLC-4 | CLCN4 | AL, IL, RL | −0.79 (AL); −0.73 (IL); −1.03 (RL) | Cl−/H+ antiporter | |

| CLC-7 | CLCN7 | CA | −0.72 | Cl−/H+ antiporter | |

| Connexins and pannexins | |||||

| Cx43 | GJA1 | AL, CA, RL | +1.53 (AL); +1.12 (CA); +1.19 (RL) | Monovalent and divalent ions | Astrocytes1, astrocytes2 |

| Cx32 | GJB1 | AL, CA, IL, RL | −1.6 (AL); −1.5 (CA); −1.85 (IL); −2.44 (RL) | Monovalent and divalent ions | Oligo5 |

| CX37 | GJA4 | IL | +1.19 | Monovalent and divalent ions | Pericytes |

| Cx47 | GJC2 | AL, CA | −1.62 (AL); −1.74 (CA) | Monovalent and divalent ions | |

| Panx1 Others | PX1 | IL | +0.56 | Monovalent and divalent ions | |

| Piezo2 | PIEZO2 | AL, CA, IL, RL | −0.92 (AL); −1.01 (CA); −0.93 (IL); −1.49 (RL) | Ca2+ -permeable | Oligo1, Oligo6 |

| CFTR | CFTR | AL, CA, IL, RL | −1.22 (AL); −1.37 (CA); −1.77 (IL); −1.86 (RL) | Cl−-permeable | Oligo1 |

| Hv1 | HVCN1 | CA, RL | +0.71 (CA); +0.92 (RL) | H+-selective | |

| Navi2.1 | NALCN | AL, IL, RL | −0.49 (AL); −0.73 (IL); −0.88 (RL) | Sodium leak channel, non-selective | |

| Orai3 | ORAI3 | AL, RL | +0.87 (AL); +1.25 (RL) | Store-Operated Ca2+ entry | |

| Aquaporin 1 | AQP1 | CA, IL | −1.03 (CA); −0.12 (IL) | Water, ammonia, H202 permeability | Astrocytes1, astrocytes2 |

| CATSPERG | CATSPERG | CA | +0.7 | Ca2+ -permeable | |

| CATSPERE | CATSPERE | IL | −0.48 | Ca2+ -permeable | |

The expression profile of the ion channel genes uniquely expressed in different lesion types. (A) Left panel: The Venn diagram represents the number of overlapping and lesion-specific differentially expressed genes coding for ion channels in chronic active (CA), active (AL), inactive (IL), and remyelinating (RL) lesions and in normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) compared to control white matter. Right panel: The heatmap shows two genes, coding for ion channels KCNH8 and TRPV6 that are significantly altered in all lesion types compared to control white matter. Scale bar indicates fold changes. (B) The Venn diagram, the heatmap, and the scale bar show the single ion channel gene, KCNK10, which is uniquely downregulated in active lesion (AL). (C) The Venn diagram, the heatmap, and the scale bar show the eight genes coding for ion channels that are uniquely significantly differentially dysregulated in inactive lesion (IL). (D) The Venn diagram, the heatmap, and the scale bar show the 33 genes coding for ion channels that are significantly and differentially dysregulated compared to control white matter in chronic active lesion (CA). The red box in Venn diagrams marks the genes that are specifically dysregulated in the corresponding type of lesion.

Table 2

Profiling expression of unique gene in lesions in WM clusters of healthy and SPMS braina.

| Protein | Gene | Neuron | Astrocyte | OPC | COP | ImOLG | Oligo | Microglia | Pericyte |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+ channels | |||||||||

| Kv1.1 | KCNA1 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Kv1.2 | KCNA2 | + | +/– | +/– | +/– | – | +/– | – | – |

| Kv1.4 | KCNA4 | +/– | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kv2.1 | KCNB1 | + | +/– | +/– | + | +/– | +/– | – | + |

| Kv2.2 | KCNB2 | ++ | +/– | – | +/– | +/– | +/– | – | – |

| Kv3.3 | KCNC3 | + | +/– | – | +/– | +/– | +/– | +/– | – |

| Kv4.2 | KCND2 | +++ | + | ++++ | +++ | + | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| Kv7.2 | KCNQ2 | + | +/– | + | + | +/– | +/– | – | +/– |

| Kv7.3 | KCNQ3 | +++ | + | + | + | ++ | +/– | +++ | +/– |

| Kv7.5 | KCNQ5 | ++++ | + | +/– | + | + | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| Kv8.1 | KCNV1 | + | – | – | +/– | +/– | – | – | – |

| Kv9.2 | KCNS2 | + | – | – | +/– | – | – | – | – |

| Kv10. 2/EAG2 | KCNH5 | + | +/– | +/– | + | +/– | +/– | – | – |

| Kv11.3/ERG3 | KCNH7 | +++ | +/– | – | + | + | +/– | – | – |

| Kv12.1/ELK1 | KCNH8 | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +/– | +/– |

| TREK1 | KCNK2 | + | +/– | + | +/– | – | – | – | – |

| TREK2 | KCNK10 | + | +/– | +/– | + | +/– | +/– | – | – |

| KCa2.3 | KCNN3 | + | ++ | + | + | + | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| KNa1.1 | KCNT1 | + | – | – | +/– | +/– | – | – | – |

| Kir3.2 | KCNJ6 | + | +/– | + | + | – | + | – | – |

| Kir5.1 | KCNJ16 | – | +/– | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| Na+ channels | |||||||||

| Nav1.1 | SCN1A | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | + | +/– | – | – |

| Nav1.2 | SCN2A | +++ | + | +/– | + | + | +/– | – | +/– |

| Nav1.3 | SCN3A | ++ | +/– | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | +/– |

| Nav1.6 | SCN8A | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Nav1.9 | SCN11A | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Ca2+ channels | |||||||||

| Cav1.2 | CACNA1C | +++ | + | + | + | + | +/– | – | +++ |

| Cav1.3 | CACNA1D | ++ | +/– | + | + | + | +/– | + | – |

| Cav2.1 | CACNA1A | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | + | +/– | + | +/– |

| Cav2.3 | CACNA1E | ++ | +/– | +/– | + | + | +/– | – | – |

| Cav3.1 | CACNA1G | + | – | +/– | +/– | – | – | – | – |

| Cav3.2 | CACNA1H | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Cav3.3 | CACNA1I | + | – | – | +/– | – | – | – | – |

| Ryanodine | |||||||||

| Ryr2 | RYR2 | ++++ | + | +/– | + | + | + | +/– | + |

| Ryr3 | RYR3 | + | +++ | + | + | + | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| TRP channels | |||||||||

| TRPM2 | TRPM2 | + | +/– | – | +/– | + | – | + | +/– |

| TRPP1 | PKD2 | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | + |

| TRPP3 | PKD2L2 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| TRPV1 | TRPV1 | +/– | +/– | – | +/– | – | +/– | – | – |

| TRPV6 | TRPV6 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Cl− channels | |||||||||

| CLC−2 | CLCN2 | +/– | +/– | +/– | +/– | +/– | + | – | – |

| CLC−7 | CLCN7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/– |

| Connexins | |||||||||

| Cx37 | GJA4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ++ |

| Pannexin | |||||||||

| Px1 | PANX1 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| Catsper | |||||||||

| CATSPERG | CATSPERG | +/– | +/– | – | +/– | +/– | +/– | – | – |

| CATSPERE | CATSPERE | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

+/– (log scale > 0.01 ≤ 0.1); + (log scale > 0.1 ≤ 0.5); ++ (log scale > 0.6 ≤ 1); +++ (log scale >1.1 ≤ 1.5); ++++ (log scale > 1.5); – (log scale 0); n.d., not detected; red (+), highly expressed gene in the cluster if compared to the rest of the clusters.

Note, that in the database, some of the clusters encompass both control and MS samples and, therefore, the mean can represent a combination of counts from control and MS brain.

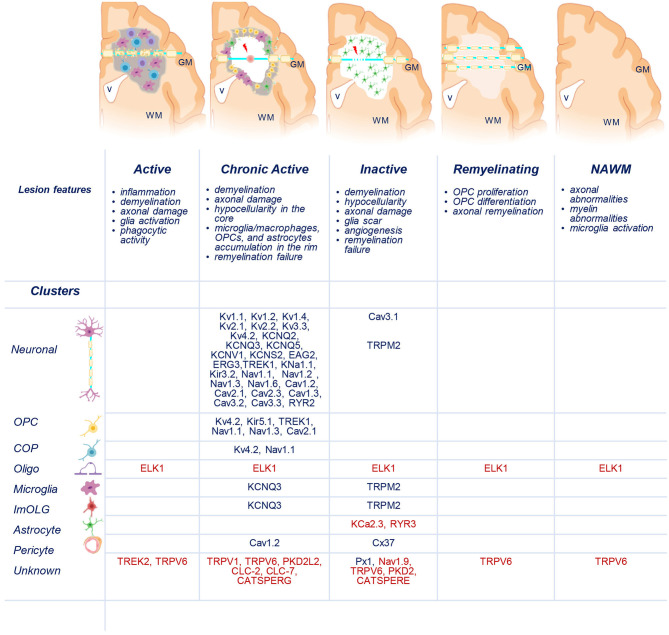

Distribution of uniquely dysregulated genes encoding ion channels in SPMS lesions. Schematic representation of active (AL), chronic active (CA), inactive (IL), and remyelinating (RL) lesions, and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM). Upregulated (blue) and downregulated (red) ion channels encoded by uniquely dysregulated genes are listed according to their expression in the lesions and in neuronal, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), committed OPCs (COPs), oligodendrocytes (Oligo), microglia, immune oligo (ImOLG), astrocyte, pericyte, and unknown clusters. GM, gray matter; WM, white matter; v, brain ventricle. Gray areas indicate active inflammatory lesion, white areas indicate demyelinated inactive lesions, red spot indicates tissue damage, red arrow indicates axonal dysfunction. Source icon is from Biorender.com.

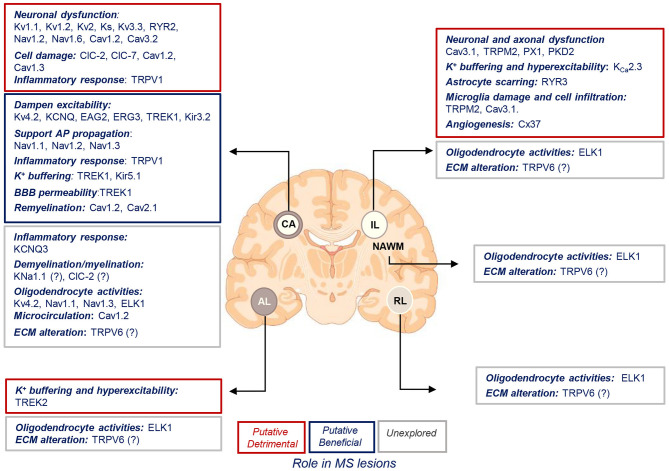

The goal of the present review is to discuss the current knowledge on the expression and function of ion channels that turned out to be significantly and uniquely dysregulated in WM lesions of SPMS brain. We summarize the information in the context of human MS and the related experimental models (Tables 1–3, Figure 4).

Table 3

Expression and role of unique dysregulated ion channels in experimental models of MS.

| Gene/protein | Distribution, localization | Cellular functions during physiological conditions | WM in MS models | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alterations | Role | |||

| KCNA1/Kv1.1 | JPN of myelinated axons | Regulate AP propagation and neural excitability | Redistribution to internodes and nodal segments, upregulation | Hyperpolarise axonal Vrest, affect AP threshold, impair AP conduction |

| Microglia, astrocyte (t), OPCs (t) | Proliferation, cell activation | |||

| KCNA2/Kv1.2 | JPN of myelinated axons | Regulate AP propagation and neural excitability | Redistribution to internodes and nodal segments, upregulation | Hyperpolarise axonal Vrest, affect AP threshold, impair AP conduction |

| Reactive astrocyte, microglia, OPC | Proliferation, cell activation | |||

| KCNA4/Kv1.4 | Axons (HP) | Regulate AP propagation and neural excitability | Upregulation in astrocytes and OPCs around EAE lesions | Deficiency ameliorated EAE course in KO mice, but have no effect on demyelination/remyelination in the cuprizone model |

| Reactive astrocyte, OPCs | Proliferation | |||

| KCNB1/Kv2.1 | Soma, proximal dendrites, AIS Microglia, OPCs (t) | Influence AP duration during high frequency firing, regulate neuronal excitability | Unknown in WM Downregulation in motor neurons of GM spinal cord during EAE | Unknown |

| KCNB2/Kv2.2 | Soma, proximal dendrites, AIS Not detected in glia | Influence AP duration during high frequency firing, regulate neuronal excitability | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNC3/Kv3.3 | Axons, somatodendritic compartment Astrocyte, microglia (t), OPCs (t) | Regulate AP firing at high frequency | Upregulation in some injured WM axons | Unknown |

| KCND2/Kv4.2 | Soma, dendrites Astrocyte (t), OPCs (t), microglia (t) | Regulate threshold for AP initiation and repolarization, frequency-dependent AP broadening, AP back-propagation | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNQ2/Kv7.2 | AIS, nodes of Ranvier OPCs, microglia | Stabilize Vrest, regulate activity of NaV-channels, accelerate AP upstroke, influence neuronal subthreshold excitability, regulate spike generation, and repetitive firing | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNQ3/Kv7.3 | AIS, nodes of Ranvier Microglia (pro-inflammatory), OPCs, astrocyte (t) | Stabilize Vrest, regulate activity of NaV-channels, accelerate AP upstroke, influence neuronal subthreshold excitability, regulate spike generation and repetitive firing | Unknown in WM Upregulated in demyelinated neocortical axons of L5 pyramidal neurons in the cuprizone model. | Unknown in WM Ensure AP conduction in demyelinated GM axons, decrease excitability |

| KCNQ5/Kv7.5 | Soma, dendrites Astrocyte, OPCs, microglia | Contributes to AHP currents in the HP | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNV1/Kv8.1 | Unknown Oligo lineage (t) | Co-assemble with Kv2.1, reduce Kv2.1 current density which may lead to AP broadening and hyper-synchronized high-frequency firing | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNS2/Kv9.2 | Unknown Oligo lineage (t) | Co-assemble with Kv2.1 | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNH5/EAG2 | Unknown Astrocyte (t), OPCs (t) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNH7/ERG3 | Unknown Astrocyte (t), OPCs (t), microglia (t) | Dampen excitability, stabilize Vrest | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNH8/ELK1 | Unknown OPCs (t) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNK2/TREK1 | Axons, and node of Ranviers in afferent myelinated nerve Astrocyte, microglia (t) OPCs (t) | Contribute to “leak” K+-current, help establishing and maintaining Vrest, regulate neuronal excitability, ensure AP repolarization at nodes of Ranvier in afferent myelinated fibers Contribute to passive membrane K+ conductance, glutamate release | Unknown | Deficiency aggravates EAE course in KO mice Channel activation reduces CNS immune cell trafficking across BBB and attenuate EAE course |

| KCNK10/TREK2 | Unknown Astrocyte OPCs (t) | Contribute to “leak” K+-current, help establishing and maintaining Vrest

Contribute to K+ buffering, glutamate clearance | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNT1/KNa1.1 | Soma, axons Astrocytes (t) | Regulate the generation of slow afterhyperpolarization, firing patterns, and setting and stabilizing the Vrest | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNN3/KCa2.3 | Dendrites, AIS Astrocyte, microglia, oligo lineage (t) | Regulate AP propagation and neuronal excitability, contribute to maintaining Ca2+-homeostasis K+ buffering in astrocytes Microglia proliferation and cytokines production | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNJ6/Kir3.2 | Somatodendritic compartment Astrocyte, oligo lineage (t) | K+-homeostasis, maintenance of Vrest, hyperpolarization, control of AP firing and neuronal excitability, inhibition of excitatory neurotransmitter release | Unknown | Unknown |

| KCNJ16/Kir5.1 | Somatodendritic compartment, dendritic spines Astrocyte, oligo lineage, microglia (t) | Silent channel when combined with Kir2.1. When combined with Kir4.1, build channels with larger conductance and greater pH-sensitivity. Plays a role in synaptic transmission Chemoreception K+ buffering | Unknown | Unknown |

| SCN1A/Nav1.1 | Somatodendritic compartment, AIS, nodes of Ranvier Microglia, astrocyte, OPCs (t) | Saltatory conduction, maintenance of sustained firing, control of excitability Microglia phagocytosis, cytokine release | Increase or no change; localize along the demyelinated regions | Unknown |

| SCN2A/Nav1.2 | AIS, immature nodes of Ranvier, along the non-myelinated axons Astrocyte, pre-oligodendrocytes | Back-propagation of AP into the somatodendritic compartment, may support slow spike propagation Oligo maturation | Increase of diffuse distribution along demyelinated axons in various mouse models; no change in myelin-deficient rat Upregulated in astrocytes during EAE | Unclear. Suggested: preservation of AP propagation, or axonal damage |

| SCN3A/Nav1.3 | Somatodendritic compartment, along the axons including myelinated fibers Astrocyte oligo lineage (t) | AP initiation and propagation, proliferation and migration of cortical progenitors | No change in the optic nerve | Unknown |

| SCN8A/Nav1.6 | AIS, nodes of Ranvier; low density on cell soma, dendritic shafts, synapses Astrocyte, microglia oligo (t) | AP initiation and propagation, neuronal excitability | Decrease at the nodes of Ranvier, increase of diffuse distribution along the damaged axons, no change at AIS Upregulated in microglia/macrophages during EAE | May trigger Na+ increase in axoplasm, reversal of NCX, and intra-axonal Ca2+ overload. Deletion improves axonal health during EAE |

| SCN11A/Nav1.9 | Soma, proximal processes Negligible in all glial cells (t) | Regulate excitation, control activity-dependent axonal elongation, mediate sustained depolarizing current upon activation of muscarinic receptors | Unknown | Unknown |

| CACNA1C/CaV1.2 | Somatodendritic compartment (synaptically, extrasynaptically), axons, axonal terminals (extrasynaptically), pioneer axons during development Astrocyte, oligo lineage, reactive microglia | Synaptic modulation, propagation of dendritic Ca2+ spikes, regulation of glutamate receptor trafficking, CREB phosphorylation, coupling of excitation to nuclear gene transcription, modulation of long-term potentiation, neurites growth and axonal pathfinding during development Astrogliosis OPCs development and myelination | Unknown | Unknown. Suggested: Neurodegeneration because L-type VGCCs blockers attenuate mitochondrial pathology in nerve fibers and axonal loss Deletion in astrocyte- reduces cell activation and pro-inflammatory mediators release in the cuprizone model Deletion in OPCs reduced remyelination in the cuprizone model |

| CACNA1D/CaV1.3 | Somatodendritic compartment, axonal cylinders Astrocyte, microglia oligo lineage | Pacemaking activity, spontaneous firing, Ca2+-dependent post-burst after-hyperpolarization, Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling pathways, regulation of morphology of dendritic spines and axonal arbores Oligodendrocyte-axon signaling, release of pro-inflammatory mediators by microglia | Unknown | Unknown. Suggested: neuroprotection because L-type VGCCs blockers attenuate mitochondrial pathology in nerve fibers and axonal loss |

| CACNA1A/CaV2.1 | Axonal synaptic terminals, axonal shafts in WM, somatodendritic compartment Reactive astrocyte OPCs, premyelinating oligo, microglia (t) | Neurotransmitter release at neuronal and neuron-glia synapses, regulation of BK and SK channels, control of neuronal firing, regulation of gene expression, local Ca2+ signaling, and cell survival Calcium influx in oligo upon neuronal activity | Unknown | Unknown |

| CACNA1E/CaV2.3 | Dendritic spines, axonal terminals Astrocyte, oligodendrocyte | Neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity, regulation of BK, SK, and KV4.2 channels | Unknown | Unknown |

| CACNA1G/CaV3.1 | Somatodendritic compartment, AIS Astrocyte (t) oligo lineage | Generation and timing of APs, regulation of neuronal excitability, rhythmic AP bursts in thalamus, neuronal oscillations, neurotransmitter release | Unknown | T-cells from KO mice show decreased cytokine release Deficiency in KO mice inhibits the autoimmune response in the EAE model |

| CACNA1H/CaV3.2 | Somatodendritic compartment, AIS Astrocyte oligo lineage | Generation and timing of APs, regulation of neuronal excitability, rhythmic AP bursts in thalamus, neuronal oscillations, neurotransmitter release | Unknown | Unknown |

| CACNA1I/CaV3.3 | Somatodendritic compartment | Generation and timing of APs, regulation of neuronal excitability, rhythmic AP bursts in thalamus, neuronal oscillations, neurotransmitter release | Unknown | Unknown |

| RyR2 | Along ER (also in axons) Astrocyte, oligo lineage | Ca2+ release from the ER into the cytoplasm, vesicle fusion, neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity, growth cone dynamics | Unknown | Unknown |

| RyR3 | Along ER (also in axons) Astrocyte, OPCs, oligodendrocytes | Ca2+ release from the ER into the cytoplasm, vesicle fusion, neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity, growth cone dynamics Astrocyte motility OPCs development | Unknown | Unknown |

| TRPV1 | Soma, post-synaptic dendritic spines, synaptic vesicles Astrocyte, microglia, oligodendrocytes | Regulation of Ca2+-signaling, synaptic plasticity Astrocyte: migration, chemotaxis, activation during stress, inflammasome activation Microglia: migration, cytokine production, ROS generation, phagocytosis, polarization, cell death | Suggested a main role in regulating microglia inflammatory response | Both detrimental and beneficial effects have been described in EAE disease |

| TRPV6 | Unknown Astrocyte (t) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| TRPM2 | Soma and neurites in neuronal cultures Microglia, astrocyte (t), oligodendrocyte (t) | Contribute to synaptic plasticity and play an inhibitory role in neurite outgrowth Microglia activation and generation of proinflammatory mediators | Upregulated in monocyte-lineage cells | TRPM2 deficiency reduce monocyte infiltration in EAE |

| PKD2/TRPP1 | ER, primary cilia, and plasma membrane Astrocyte (t), microglia (t), oligo lineage (t) | Maintenance of Ca2+-homeostasis, cell proliferation | Unknown | Unknown |

| PKD2L2/TRPP3 | Unknown Astrocyte (t), microglia (t) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| CLCN2/CLC-2 | Plasma membranes, intracellular membranes Astrocyte, OPCs, microglia | Maintenance of low intracellular Cl− level, control of cell volume homeostasis, regulation of GABAAR-mediated synaptic inputs, regulation of neuronal excitability Interacts with AQP4 in astrocytes, regulates OPCs differentiation, contribute to volume regulation and phagocytosis in microglia | Unknown | Unknown |

| CLCN7/CLC-7 | Lysosomes Microglia, astrocyte (t), oligo lineage (t) | Suggested function in the neuronal endo-lysosomal pathway Regulate lysosomal acidification in activated microglia | Unknown | Unknown |

| GJA4/CX37 | Largely expressed in vascular cells | Regulate vasomotor activity, endothelial permeability, and maintenance of body fluid balance | Unknown | Unknown |

| PANX1/Px1 | Soma, dendrites, axons Astrocyte, OPCs microglia | Paracrine and autocrine signaling, ATP-sensitive ATP release in complex with P2X7Rs, intercellular propagation of Ca2+-waves, cell differentiation, migration, synaptic plasticity, memory | Unknown | Panx-1 induced ATP release and inflammasome activation contribute to WM damage during EAE Inhibition of Panx1 using pharmacology or gene disruption delays and attenuates disease course in EAE and cuprizone model |

| CATSPERG | Unknown Oligo lineage (t) Microglia (t) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| CATSPERE | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

AHP, afterhyperpolarization; AIS, axon initial segment; AP, action potential; BK, big-conductance Ca2+-activated K+-channels; ER, endoplasmatic reticulum; GABAAR, ionotropic gamma aminobutyric acid A receptor; HP, hippocampus; JPN, juxtaparanodal regions; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; SCI, spinal cord injury; SK, small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+-channels; SSCx, somatosensory cortex; t, transcipts; Vrest, resting membrane potential.

Putative roles of ion channels encoded by uniquely dysregulated genes in SPMS lesions. Schematic illustration of the putative detrimental (red box), putative beneficial (blue box), and unexplored (gray box) functional roles of ion channel encoded by the uniquely dysregulated genes in active (AL), chronic active (CA), inactive (IL), and remyelinating (RL) lesions, and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) of SPMS brain. Source icon is from Biorender.com.

K+ Channels

Voltage-Gated K+ Channels (Kv)

Kv channels are composed of four α-subunits that assemble as homo- or hetero-tetramers to form a membrane pore. Forty human genes encode for Kv α-subunits representing 12 families. KV1–Kv4 (Shaker, Shab, Shaw, and Shal), KV7 (KCNQ), and KV10–KV12 (eag, erg, and elk) α-subunits produce functional channels, while Kv5, Kv6, Kv8, and Kv9 fail to produce currents when expressed alone in heterologous expression system and are considered modulatory subunits for Kv2-subfamily. The diversity of Kv channels is further increased by the ability of α-subunits to combine with auxiliary subunits, which regulate gating properties.

Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4 (KCNA1, KCNA2, and KCNA4)

KCNA genes encode for low-threshold voltage-activated Kv1 (Kv1.1–1.8) channels, of which Kv1.1–Kv1.6 are expressed in the brain (Chittajallu et al., 2002; Vautier et al., 2004; Vacher et al., 2008; Rasmussen and Trimmer, 2019). Kv1 channels display little/no inactivation, resulting in sustained delayed rectifier K+ currents, with the exception of Kv1.4, which underlies transient A-type K+ current.

Neurons

Kv1.1 expression is highest in the brainstem, while Kv1.4 > Kv1.2 represent the main Kv1 subunits in the hippocampus (Trimmer, 2015). Kv1.1 channels, in association with Kv1.2, cluster in the juxtaparanodal regions of axons under the myelin sheath and regulate action potential (AP) propagation and neural excitability (Wang et al., 1993; Trimmer and Rhodes, 2004; Ovsepian et al., 2016). Mutations of Kv1 channels result in hyper-excitability, episodic ataxia, myokymia, and epilepsy (Allen et al., 2020).

Glia

Mouse astrocytes express low levels of Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4 transcripts (Smart et al., 1997), but Kv1.2 and Kv1.4 expression is high in reactive rat astrocytes (Akhtar et al., 1999). Kv1.1 transcripts and proteins are highly expressed in C6 glioma cells. Rodent oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) express Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4 transcripts (Attali et al., 1997; Chittajallu et al., 2002; Falcao et al., 2018; Batiuk et al., 2020) but only Kv1.4 and low level of Kv1.2 proteins (Attali et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 1999). In OPCs and astrocytes, the Kv1 subunits regulate cell growth and cell cycle progression, e.g., Kv1.4 overexpression in vitro increases OPCs proliferation (Schmidt et al., 1999) while deletion decreases it (Gonzalez-Alvarado et al., 2020). Recent RNA-seq did not detect Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4 in mouse microglia (Hammond et al., 2019), but earlier studies found Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 mRNAs and/or proteins in BV2 microglia, rat cultured microglia, and amoeboid microglia within corpus callosum during development, but barely in resting microglia by P21 (Fordyce et al., 2005; Li F. et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009). In microglia, Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 expression was linked to cell activation (Eder, 1998), and their upregulation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), ATP, or hypoxia is involved in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and intracellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) (Li F. et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq found upregulation of Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4 transcripts in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq detected significant Kv1.2 expression in neuronal clusters, slight increase of Kv1.4 transcripts in neuronal but not glial clusters, and no Kv1.1 transcript (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019).

The CA lesion is characterized by ongoing tissue damage and, functionally, Kv1.2 upregulation in CA lesions may be a hallmark of axonal damage. While recent data found that KCNA1 gene is downregulated during demyelination in the cuprizone model (Martin et al., 2018), in animal models of MS, Kv1.2 (and also Kv1.1) ectopically redistributes to nodes and internodes of WM axons (McDonald and Sears, 1969; Wang et al., 1995; Sinha et al., 2006; Jukkola et al., 2012; Zoupi et al., 2013; Kastriti et al., 2015), while in human MS, the dislocation of Kv1.2 channels is associated with paranodal pathology, particularly in NAWM regions, and contributes to axonal dysfunction (Howell et al., 2010; Gallego-Delgado et al., 2020). The upregulated and redistributed Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 channels may hyperpolarize the axonal resting membrane potential (Vrest), elevate the amount of depolarization necessary for AP initiation, and impair AP conduction (Wang et al., 1995; Sinha et al., 2006; Jukkola et al., 2012). Pharmacological inhibition of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 channels, e.g., with 4-aminopyridine, enhances axonal conduction and improves MS symptoms (Lugaresi, 2015).

It is difficult to speculate regarding Kv1.4 function in MS because data are not consistent. In animal models of MS and spinal cord injury (SCI), this developmentally restricted subunit re-appears/increases in OPCs, OLs, and astrocytic processes around lesion sites (Herrero-Herranz et al., 2007; Jukkola et al., 2012), but not in WM axons or microglia (Edwards et al., 2002; Jukkola et al., 2012). Mice lacking Kv1.4 exhibit reduced myelin loss in the spinal cord WM during EAE but no change of demyelination/remyelination in the corpus callosum in the cuprizone model (Gonzalez-Alvarado et al., 2020). However, it is unclear whether function of Kv1.4 subunits is relevant for glial cells in human MS because snRNA-seq barely detected Kv1.4 transcripts in glia clusters (Table 2).

Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 (KCNB1 and KCNB2)

Kv2 channels (encoded by KCNB1 and KCNB2 genes) mediate high-voltage-activated slowly inactivating delayed rectifier K+ currents (Guan et al., 2007). Kv2.1 channels can assemble with electrically silent KvS subunits, resulting in greater variability of Kv2 currents (Trimmer, 2015; Johnson et al., 2019).

Neurons

High-density clusters of Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 localize to soma, proximal dendrites, and axonal initial segment (AIS). Kv2 channels influence AP duration during high-frequency firing and regulate neuronal excitability (Guan et al., 2007). Kv2.1 mutations are associated with neonatal encephalopathy epilepsies and neurodevelopmental delays (Torkamani et al., 2014; Thiffault et al., 2015; de Kovel et al., 2017).

Glia

RNA-seq detected KCNB1 gene in mouse OPC and microglia (Falcao et al., 2018; Hammond et al., 2019).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq revealed upregulation of Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 transcripts in CA lesions of SPMS brain (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020), while snRNA-seq found Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 in neuronal clusters (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019). During EAE, Kv2.1 protein expression was downregulated in spinal cord motor neurons (Jukkola and Gu, 2015). Remarkably, Kv2.1 channels exist as freely dispersed conducting channels, or form electrically silent somatodendritic clusters (Schulien et al., 2020). Upregulated clustered Kv2.1 channels promote functional coupling of L-type Ca2+ channels in plasma membrane to ryanodine receptors (RyRs) of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Deutsch et al., 2012; Kirmiz et al., 2018; Vierra et al., 2019) and may modulate intracellular Ca2+ level contributing to cell damage, while dispersal of Kv2.1-clusters blocks apoptogenic K+ currents and provides neuroprotection (Sesti et al., 2014; Justice et al., 2017). Hence, to elucidate the functional role of Kv2 upregulation in MS (Table 1), it will be important to determine whether it reflects an increase in clustered or dispersed Kv2 channels.

Kv3.3 (KCNC3)

The KCNC3 gene encodes for the Kv3.3 subunit, which, together with Kv3.1, Kv3.2, and Kv3.4, belongs to the Kv3 channel subfamily (Shaw). The Kv3.3 and Kv3.4 mediate transient A-type K+ currents, while Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 mediate sustained K+ currents.

Neurons

Kv3 channels localize to axonal and somatodendritic domains, and play a critical role in regulating AP firing at high frequency (Rasmussen and Trimmer, 2019). KCNC3 mutations result in spinocerebellar ataxia type-13 and cerebellar neurodegeneration (Rasmussen and Trimmer, 2019).

Glia

Cortical and hippocampal astrocyte cultures express Kv3.3 and Kv3.4 mRNAs and proteins (Bekar et al., 2005; Boscia et al., 2017). KCNC3 mRNA was detected in mouse OPCs and microglia (Larson et al., 2016; Falcao et al., 2018).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq showed significant Kv3.3 upregulation in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1), while snRNA-seq revealed its predominant distribution in neuronal clusters (Table 2; Jakel et al., 2019). Kv3.3 may play a detrimental role in MS because it increases in injured WM axons during EAE progression in mice and in human MS lesions (Jukkola et al., 2017), and the deletion of Kv3.1, which forms hetero-tetramers with Kv3.3, reduced EAE severity in mice (Jukkola et al., 2017).

Kv4.2 (KCND2)

The KCND2 gene encodes for the Kv4.2 subunit that (together with Kv4.1 and Kv4.3) is a member of the Kv4 channel subfamily (Shal) and is highly expressed in the brain (Alfaro-Ruiz et al., 2019). Kv4 channels activate at subthreshold potentials and then inactivate and recover rapidly. They mediate transient A-type K+ current (Bahring et al., 2001; Birnbaum et al., 2004).

Neurons

Kv4.2 subunits are highly expressed in soma and dendrites of hippocampal neurons and interneurons. They regulate the threshold for AP initiation and repolarization, frequency-dependent AP broadening, and AP back-propagation (Nerbonne et al., 2008). Kv4.2 mutations are associated with infant-onset epilepsy and autism.

Glia

Kv4.2-transcripts were found in mouse astrocytes (Bekar et al., 2005) and OPCs, but only at very low levels in microglia (Falcao et al., 2018; Hammond et al., 2019; Batiuk et al., 2020).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq found significant Kv4.2 upregulation in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq reported significant expression of Kv4.2 transcripts in neuronal, OPCs, and committed OPCs (COP) clusters (Table 2; Jakel et al., 2019). Kv4.2 subunit may contribute to oligodendrocyte dysfunction in SPMS brain because dysregulated KCND2 transcripts are associated with oligodendrocyte dysfunction in mental illnesses (Vasistha et al., 2019).

Kv7.2, Kv7.3, and Kv7.5 (KCNQ2, KCNQ3, and KCNQ5)

The KCNQ genes encode for Kv7.1–Kv7.5 (KCNQ1–KCNQ5) family members that underlie a voltage-gated non-inactivating outward K+ current, known as M current (IM).

Neurons

The Kv7.2/3 or Kv7.3/5 hetero-tetramers represent the dominant subunit composition in neurons (Wang et al., 1998; Cooper et al., 2000; Kharkovets et al., 2000), while Kv7.4/Kv7.5 is dominant in vascular smooth muscles (Brueggemann et al., 2014). The Kv7.2- and Kv7.3 subunits co-cluster with Nav channels at AIS and nodes of Ranvier in rodent somatosensory cortex and spinal cord WM and gray matter (GM) (Pan et al., 2006; Cooper, 2011; Battefeld et al., 2014). Kv7.5 localizes to soma and dendrites of cortical and hippocampal neurons and contributes to afterhyperpolarization currents (Tzingounis et al., 2010). The Kv7 channels stabilize Vrest, influence neuronal subthreshold excitability, and regulate spike generation (Jentsch, 2000; Miceli et al., 2008). By reducing the steady-state inactivation of nodal Nav channels, the Kv7 channels increase the availability of transient Nav currents at nodes of Ranvier, thereby accelerating the AP upstroke and elevating short-term axonal excitability (Hamada and Kole, 2015). In the perisomatic region, Kv7 channels counteract the persistent Nav current and restrain repetitive firing (Pan et al., 2006; Cooper, 2011). Variants of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 or KCNQ4 genes cause developmental/epileptic disorders and hearing loss (Soldovieri et al., 2011; Miceli et al., 2013).

Glia

KCNQ3 gene is expressed in spinal cord WM astrocytes (Devaux et al., 2004), while KCNQ5 is expressed in rat retinal astrocytes (Caminos et al., 2015). The KCNQ2-5 mRNAs and proteins were detected in rat cortical OPCs and microglia cultures, while differentiated oligodendrocytes showed weak KCNQ4 expression (Wang et al., 2011; Vay et al., 2020).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq found upregulation of KCNQ2-3-5 transcripts in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq reported KCNQ2-3-5 expression in neuronal clusters and KCNQ3 expression in immune oligodendroglia (ImOLG) and microglia/macrophages clusters (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019). Kv7.3 upregulation may reflect increased necessity of the channels along the axons because Kv7.3 subunit extensively redistributes to internodes of acutely and chronically demyelinated GM axons in the cuprizone model (Hamada and Kole, 2015). It is tempting to speculate that Kv7 upregulation may be beneficial during MS. First, Kv7 channels may increase the availability of transient Nav current via membrane hyperpolarization supporting AP conduction in demyelinated axons (Battefeld et al., 2014). Second, Kv7 channels may mitigate inflammation-induced neuronal excitability because, following LPS exposure, the IM inhibition underlies hyperexcitability of hippocampal neurons that is reversed by a nonselective Kv7-opener retigabine (Tzour et al., 2017). Although retigabine also exerts neuroprotective effects in several neurodegenerative conditions (Boscia et al., 2006; Nodera et al., 2011; Wainger et al., 2014; Bierbower et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Vigil et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020), a clinical trial with retigabine analog flupirtine failed to demonstrate neuroprotective effects during MS (Dorr et al., 2018). Furthermore, blockade of Kv7 channels with XE-991 inhibited migration of LPS-treated pro-inflammatory microglia in vitro (Vay et al., 2020), suggesting that these channels may promote the pro-inflammatory role of microglia also during MS. Hence, neuronal and glial Kv7 channels may have diverse functions during MS.

Kv8.1 and Kv9.2 (KCNV1 and KCNS2)

Neurons

KCNV1 and KCNS2 genes encode for electrically silent (KvS) Kv8.1- and Kv9.2 subunits that assemble into hetero-tetrameric channels with Kv2 subunits (Bocksteins, 2016). A number of channelopathies is ascribed to KvS subunits (Salinas et al., 1997a; Liu et al., 2016; Allen et al., 2020), pointing to their important physiological role.

Glia

KCNV1 and KCNS2 transcripts were found in oligodendrocyte lineage cell (Marques et al., 2016).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq showed upregulation of KCNV1 and KCNS2 genes in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq detected KCNV1 and KCNS2 in neuronal clusters (Table 2; Jakel et al., 2019). Co-assembly between Kv8.1 and Kv2.1 reduces Kv2.1 current density (Hugnot et al., 1996; Castellano et al., 1997): the high stoichiometry of the Kv8.1 subunit suppresses surface expression and favors retention of heteromeric channels in the ER (Salinas et al., 1997b). Neurons with reduced Kv2.1-mediated currents demonstrate broadened APs (Du et al., 2000) underlying hyper-synchronized high-frequency firing observed during epilepsy. Hence, upregulated KvS subunits in CA lesions may influence the localization of clustered Kv2 subunits in SPMS brain and affect AP firing and/or propagation.

Eag2, erg3, and elk1 (KCNH5, KCNH7, and KCNH8)

KCNH genes encode for Kv10–Kv12 subfamilies, all orthologs of the Drosophila ether-àgo-go (EAG) channels. They include two eag (Kv10), three eag-related (erg/Kv11), and three eag-like (elk/Kv12) K+ channels that can form heteromeric channels within each subfamily (Rasmussen and Trimmer, 2019).

Neurons

All EAG channels are expressed in the CNS neurons (Ludwig et al., 2000; Papa et al., 2003; Zou et al., 2003), but only erg-mediated currents have been verified using suitable blockers (Bauer and Schwarz, 2018).

Glia

RNA-seq detected KCNH5, KCNH7, and KCNH8 expression in mouse OPCs (Falcao et al., 2018). KCNH5 and KCNH7 genes were found in astrocytes (Batiuk et al., 2020), while only the KCNH7 gene was detected in mouse microglia (Hammond et al., 2019). Erg-type currents were reported in neopallial microglia cultures (Zhou et al., 1998) and hippocampal astrocytes (Emmi et al., 2000; Papa et al., 2003).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq detected increased KCNH5(eag2) and KCNH7(erg3) transcripts in CA lesions and downregulation of KCNH8(elk1) transcript in all lesions and NAWM (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq found significant expression of KCNH5 and KCNH7 transcripts in neuronal clusters and KCNH8 in mature oligodendrocyte clusters (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019). The functional role of eag2, erg3, and elk1 during MS may be related to altered neuronal excitability. Indeed, human eag1 and eag2 gain-of-function mutations underlie severe neurological disorders associated with epileptic seizures (Allen et al., 2020). The erg channels that are active at subthreshold potentials stabilize the Vrest and dampen excitability (Fano et al., 2012). Erg3 knockdown in mice increases intrinsic neuronal excitability and enhances seizure susceptibility, while treatment with erg activator reduces epileptogenesis (Xiao et al., 2018). Erg3 expression is decreased in the brain of epilepsy patients. Remarkably, association of KCNH7(erg) intronic polymorphisms with MS pathogenesis was speculated although never substantiated (Martinez et al., 2008; Couturier et al., 2009).

Two-Pore Domain K+ Channels (K2P)

K2P K+ channels are encoded by 15 KCNK genes, stratified into six subfamilies: TWIK, TASK (TWIK-related acid-sensitive), TREK (TWIK-related arachidonic acid activated), THIK (tandem pore domain halothane-inhibited), TALK (TWIK-related alkaline pH-activated), and TRESK (TWIK-related spinal cord) K+ channels (Enyedi and Czirjak, 2010). K2P K+ channels contribute to “leak” K+ current, helping to establish and maintain Vrest (Enyedi and Czirjak, 2010).

TREK1 and TREK2 (KCNK2 and KCNK10)

Neurons and Glia

KCNK2 and KCNK10 genes encode for TREK-1 and TREK-2 channels, which are expressed in neurons, astrocytes, and OPC (Hervieu et al., 2001; Talley et al., 2001; Falcao et al., 2018). Only TREK-1 transcripts were detected in microglia (Hammond et al., 2019). In astrocytes, TREK channels contribute to passive conductance and glutamate release (Zhou et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2012). TREK-1 and TREK-2 may be activated by a wide range of physiological and pathological stimuli reminiscent of inflammatory environment including membrane stretch, heat, intracellular acidosis, and cellular lipids (Ehling et al., 2015).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq found upregulated TREK-1 transcripts in CA lesions, but a divergent modulation was observed for TREK-2 mRNAs in ALs (Figure 2, Tables 1, ,2;2; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). KCNK2 and KCNK10 transcripts were detected in neuronal and oligodendrocyte clusters, but scarcely observed in astrocytes (Table 2; Jakel et al., 2019). TREK-1 upregulation in CA lesions most likely reflects a protective response because TREK-1 plays a neuroprotective role during neurological diseases, including MS (Djillani et al., 2019). TREK-1 reduces neuronal excitability by hyperpolarizing the membrane potential (Honore, 2007) and is required for rapid AP repolarization at the node of Ranvier in mammalian afferent myelinated nerves, while TREK-1 loss-of-function retards nerve conduction and impairs sensory responses in animals (Kanda et al., 2019). Treatment of mice with TREK-1 activators, riluzole (Gilgun-Sherki et al., 2003), or alpha-linolenic acid attenuates EAE course (Blondeau et al., 2007), while these effects are reduced in TREK-1−/− mice (Bittner et al., 2014). TREK-1 function is also important for non-neuronal cells because aggravated EAE course in TREK-1−/− mice is associated with increased numbers of infiltrating T cells and higher endothelial expression of ICAM1 and VCAM1 (Bittner et al., 2013), and TREK-1 is reduced in the microvascular endothelium in inflammatory MS brain lesions (Bittner et al., 2013).

TREK-2 downregulation in AL, a lesion type characterized by myelin breakdown and infiltration by inflammatory cells (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020), may contribute to reduced glutamate and K+ buffering and neuronal over-excitation because TREK-2 helps maintain the membrane potential and low extracellular glutamate and K+ level during ischemia (Gnatenco et al., 2002; Rivera-Pagan et al., 2015).

Na+- and Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels

KNa1.1 (KCNT1)

Neurons

The KCNT1 and KCNT2 genes encode for Slack and Slick K+ channels that are activated by Na+ influx (Bhattacharjee and Kaczmarek, 2005). They localize to soma and axons of neurons (Bhattacharjee et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2008; Rizzi et al., 2016) and are involved in the generation of slow after-hyperpolarization, regulation of firing patterns, and setting and stabilizing the Vrest (Franceschetti et al., 2003). Alterations in KCNT1 and KCNT2 genes are linked to early-onset epileptic encephalopathies and Fragile-X-syndrome (Kim and Kaczmarek, 2014).

Glia

RNA-seq detected KCNT1 gene in mouse astrocytes (Batiuk et al., 2020).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq showed KNa1.1 upregulation in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). SnRNA-seq detected KCNT1 in neuronal clusters (Table 2). KCNT1 function in MS may be related to myelination/demyelination because severely delayed myelination occurs in patients with KCNT1 mutations (Vanderver et al., 2014). Furthermore, KCNT1 is a causative gene in infants with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy showing WM alterations (Arai-Ichinoi et al., 2016), and KCNT1 mutations occur in infant epilepsy associated with delayed myelination, thin corpus callosum, and WM hyper-intensity in MRI (McTague et al., 2013; Shang et al., 2016; Borlot et al., 2020).

KCa2.3, SK3 (KCNN3)

The KCNN3 gene encodes for the SK3 subunit of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (SK channels). They mediate Ca2+ gated K+ current and thus couple the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration to hyperpolarization of the membrane potential.

Neurons

SK3 channels are found on dendrites and AIS (Abiraman et al., 2018). They play a role in AP propagation and regulation of neuronal excitability (Stocker, 2004). They protect against excitotoxicity by maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis after NMDA receptor activation (Dolga et al., 2011).

Glia

RNA-seq detected intense KCNN3 expression in mouse astrocytes (Batiuk et al., 2020), confirming earlier studies, which showed labeling of GFAP+ processes in the supraoptic nucleus for SK3 channels and suggested the role of SK3 in astrocytic K+ buffering (Armstrong et al., 2005). Oligodendrocyte lineage cells express low levels of KCNN3 mRNA (Falcao et al., 2018), while mouse microglia does not express KCNN3 (Hammond et al., 2019). However, rat microglia in culture expresses the SK3 subunit, which is increased upon microglia activation with LPS (Schlichter et al., 2010). SK3 activation inhibited microglia proliferation, inflammatory IL-6 production, and morphological transformation to macrophages, while blocking SK3 in microglia-reduced neurotoxicity (Dolga et al., 2012).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq showed significant and unique downregulation of KCNN3 in ILs (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). SnRNA-seq revealed high KCNN3 expression in astrocyte clusters (Figure 2, Table 1; Jakel et al., 2019). ILs consist of large demyelinated areas devoid of macrophages but filled with scar-forming astrocytes showing reduced ability to buffer glutamate and K+ (Compston and Coles, 2008; Kuhlmann et al., 2017; Filippi et al., 2018; Schirmer et al., 2018). Hence, KCNN3 downregulation in MS may reflect altered function of astrocytes, e.g., K+ buffering (Armstrong et al., 2005), contributing to axonal hyper-excitability and death.

Inward Rectifier K+ Channels (Kir)

KCNJ gene family encodes Kir channels and comprises 16 subunits of Kir1–Kir7 subfamilies categorized into four groups: (1) classical (Kir2.x); (2) G-protein-gated (Kir3.x); (3) ATP-sensitive (Kir6.x); and (4) K+-transport channels (Kir1.x, Kir4.x, Kir5.x, Kir7.x) (Hibino et al., 2010). At a comparable driving force, Kir channels allow greater influx than efflux of K+-ions. Their high open probability at negative transmembrane voltages makes them well-suited to set the Vrest and to control cell excitability.

Kir3.2 (KCNJ6)

KCNJ6 gene encodes for Kir3.2 subunits, also known as G-protein-gated Kir (GIRK2) channels that are effectors for Gi/o-dependent signaling and mediate outward K+ current.

Neurons

Kir3.1/Kir3.2 hetero-tetramers are found in the somatodendritic compartment of neurons. Activation of GIRK channels is mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors including muscarinic, metabotropic glutamate, somatostatin, dopamine, endorphins, endocannabinoids, etc. GIRK channels are important for K+ homeostasis and maintenance of Vrest near the K+ equilibrium potential. GIRK current hyperpolarizes neuronal membrane reducing spontaneous AP firing and inhibiting neurotransmitter release (Luscher and Slesinger, 2010). GIRK signaling contributes to learning/memory, reward, pain, anxiety, schizophrenia, addiction, and other processes (Mayfield et al., 2015). Kir3.2 mutations in mice lead to a loss of K+ selectivity and increased Na+ permeability of the channel, resulting in the weaver phenotype (Liao et al., 1996; Surmeier et al., 1996).

Glia

Astrocytes and Müller cells express Kir3 channels (Raap et al., 2002). Kir3.2 transcripts were detected in the mouse optic nerve (Papanikolaou et al., 2020) and oligodendrocyte lineage (Falcao et al., 2018), but not in microglia (Hammond et al., 2019).

Expression and Function in MS

RNA-seq revealed KCNJ6 upregulation in the CA lesions (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq predominantly found KCNJ6 transcripts in neuronal clusters (Jakel et al., 2019; Table 1). The functional role of Kir3.2 channels in MS may be related to membrane hyperpolarization and compensation of excessive neuronal excitability driving neurodegeneration.

Kir5.1 (KCNJ16)

KCNJ16 gene encodes for Kir5.1 subunit, which forms an electrically silent channel when combined with Kir2.1 (Derst et al., 2001; Pessia et al., 2001), but is functional when combined with Kir4.1 (Konstas et al., 2003). Clustering of heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 and homomeric Kir5.1 channels on plasmalemma involves the anchoring protein PSD-95 (Tanemoto et al., 2002; Brasko et al., 2017). Heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels exhibit larger channel conductance, greater pH sensitivity, and different expression patterns if compared to Kir4.1 homomers (Tanemoto et al., 2000; Tucker et al., 2000; Pessia et al., 2001; Hibino et al., 2010).

Neurons

In cultures, Kir5.1 immunoreactivity was detected in somatodendritic compartments where PSD-95 immunoreactivity was also localized. The Kir5.1/PSD-95 complex may exist at dendritic spines in vivo and play a role in synaptic transmission (Tanemoto et al., 2002).

Glia

Kir5.1 mRNA is two-fold higher in OPCs (NG2+-glia) vs. astrocytes (Zhang et al., 2014), and mouse brain microglia expresses Kir5.1 transcript too (Hammond et al., 2019). Kir5.1 expression in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes depends on its association with Kir4.1: loss of Kir4.1 reduces Kir5.1, suggesting that altered expression/distribution of Kir5.1 may contribute to the phenotype of Kir4.1 knockout mice (Brasko et al., 2017; Schirmer et al., 2018). The oligodendroglial Kir5.1/Kir4.1 channels are important for K+ clearance (Poopalasundaram et al., 2000; Neusch et al., 2001), long-term maintenance of axonal function, and WM integrity (Kelley et al., 2018; Schirmer et al., 2018). In astrocytes, Kir5.1/Kir4.1 channels contribute to chemoreception, spatial K+ buffering, and breathing control (Mulkey and Wenker, 2011).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq revealed Kir5.1 upregulation in CA lesions (Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). SnRNA-seq detected Kir5.1 in OPCs clusters and scarcely in astrocytes. The KCNJ16 gene is upregulated during demyelination and acute remyelination in mouse cuprizone model (Martin et al., 2018). Upregulation of Kir5.1 may reflect the role of the oligodendroglial Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels in K+ clearance during MS and may represent a mechanism to compensate Kir4.1 reduction in MS brain (Schirmer et al., 2014). Alternatively, Kir5.1 upregulation may underlie reduced Kir4.1 function in MS because presence of Kir5.1 subunit confers loss of functional activity to Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels under oxidative stress (Jin et al., 2012).

Voltage-Gated Na+ Channels (Nav)

In the mammalian brain, Nav are composed of α-subunit (260 kDa) and one or several β-subunits (β1–β4, of 33–36 kDa) (Goldin et al., 2000). The α-subunit forms the channel pore and acts as a voltage sensor; β-subunits play a modulatory role and influence voltage dependence, gating kinetics, and surface expression of the channel (Goldin et al., 2000; Yu and Catterall, 2003; Namadurai et al., 2015). The nine NaV1.1–NaV1.9 α-subunits are encoded by the corresponding genes SCN1A–SCN5A and SCN8A–SCN11A. In addition, NaX isoform was described,which is encoded by the SCN6/7A gene.

NaV1.1 (SCN1A)

Neurons

NaV1.1 channels localize to the somatodendritic compartment of principal neurons and AIS of GABAergic interneurons, spinal cord motor neurons, and retinal neurons (Ogiwara et al., 2007; Duflocq et al., 2008; Dumenieu et al., 2017). NaV1.1 channels are also present at the nodes of Ranvier of the cerebellar WM, fimbria, corpus callosum, and spinal cord WM (Ogiwara et al., 2007; Duflocq et al., 2008; O'Malley et al., 2009). They play a role during saltatory conduction along myelinated axons and are essential for maintaining the sustained firing of GABAergic interneurons and Purkinje cells, thus controlling the excitability of neuronal networks (Duflocq et al., 2008; Dumenieu et al., 2017). Mutations in NaV1.1 channels result in various types of epilepsy and reduced volume of brain GM and WM (Lee et al., 2017; Scheffer and Nabbout, 2019).

Glia

Human astrocytes show negligible immunolabelling for NaV1.1 and no upregulation in the WM of MS patients (Black et al., 2010). Transcriptome analysis revealed low level of SCN1A in mouse cortical and hippocampal astrocytes (Batiuk et al., 2020). RNA-seq detected SCN1A in oligodendrocytes and OPCs throughout the CNS (Larson et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2016; Falcao et al., 2018). The functional role of NaV1.1 channels in astrocytes and oligodendroglia remains unknown. Transcriptome studies have not detected SCN1A in microglia prepared from brain homogenates (Hammond et al., 2019), but NaV1.1 protein was found in microglia derived from neonatal rat mixed glial cultures (Black et al., 2009). NaV1.1 channels may be involved in regulation of phagocytosis and/or release of IL-1α, IL-β, and TNF-α from microglia (Black et al., 2009). The NaV1.1 mRNA was detected in astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and glioblastoma samples from patients where these channels may contribute to the pathophysiology of brain tumors (Schrey et al., 2002).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq detected SCN1A upregulation in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq revealed significant expression of NaV1.1 transcripts in neuronal, committed OPC, and OPC clusters (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019). Experimental models do not provide clues regarding the functional role of NaV1.1 channels in MS: NaV1.1 expression was increased or unaltered in the optic nerve during EAE (Craner et al., 2003; O'Malley et al., 2009), while in the spinal cord, these channels clustered at the nodes of Ranvier and localized along the demyelinated regions (O'Malley et al., 2009). SCN1A upregulation in human MS may reflect the necessity of the channel for redistribution along the demyelinated axons and support of AP propagation.

NaV1.2 (SCN2A)

Neurons

The NaV1.2 channels localize to the AIS, immature nodes of Ranvier, and in non-myelinated axons during early development. As nervous system matures, NaV1.2 channels are replaced by NaV1.6 channels (Boiko et al., 2001; Osorio et al., 2005; Dumenieu et al., 2017), although in some neurons, they remain into adulthood. Nav1.2 channels of the AIS control back-propagation of APs into the somatodendritic compartment, while NaV1.6 channels are being placed at distal parts of the AIS control initiation and propagation of AP into the axon (Boiko et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2009). NaV1.2 channels are also diffusely distributed along non-myelinated axons in the adult CNS where they may support slow spike propagation (Arroyo et al., 2002; Dumenieu et al., 2017).

Glia

NaV1.2 protein was found in rat astrocytes isolated from the spinal cord and optic nerve (Black et al., 1995), but only limited NaV1.2 expression was observed in human astrocytes in control and MS tissue (Black et al., 2010). The RNA-seq detected SCN2A expression in oligodendrocytes and OPCs (Larson et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2016). Knockdown of NaV1.2 in pre-oligodendrocytes of the auditory brainstem resulted in reduced number and length of cellular processes and decreased MBP level, indicating that NaV1.2 channels are important for structural maturation of myelinating cells and myelination (Berret et al., 2017). Microglia expresses no/little functional NaV1.2 channels (Black et al., 2009; Pappalardo et al., 2016; Hammond et al., 2019).

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk RNA-seq detected upregulation of SCN2A gene in CA lesions (Figure 2, Table 1; Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020), while snRNA-seq showed abundant SCN2A expression in neuronal clusters (Tables 1, ,2;2; Jakel et al., 2019). The upregulation may reflect re-expression of NaV1.2 protein, in line with previous reports showing diffuse distribution of NaV1.2 channels along the demyelinated axons in human MS lesions within optic nerve and spinal cord (Craner et al., 2004b). Axonal NaV1.2 channels may contribute to preservation of AP propagation and re-establishment of myelin sheathes (Coman et al., 2006), as it occurs during development. On the other hand, NaV1.2 channels may promote axonal damage by increasing the intracellular Na+ concentration that triggers reversal of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and Ca2+ overload in the axoplasm (Friese et al., 2014; Schattling et al., 2016). In line with this, human gain-of-function mutation in the mouse SCN2A gene triggers axonal damage, neurodegeneration, disability, and lethality in the mouse model of MS (Schattling et al., 2016). Expression of “developmental” NaV1.2 channels in axons was also found in animal models of MS, i.e., in adult Shiverer mice that lack myelin (Westenbroek et al., 1992; Boiko et al., 2001), in transgenic mice overexpressing proteolipid protein that initially have normal myelination but then lose myelin (Rasband et al., 2003), and in the demyelinated optic nerve and spinal cord during EAE (Craner et al., 2003, 2004a; Herrero-Herranz et al., 2008). However, other data showed that in chronic spinal cord MS lesions, NaV1.2 channels localize on astrocytic processes surrounding the axons rather than on axons themselves (Black et al., 2007), and NaV1.2 expression/distribution was unchanged in the spinal cord of myelin-deficient rats (Arroyo et al., 2002).

NaV1.3 (SCN3A)

Neurons

NaV1.3 channels are highly expressed in rodent and human CNS throughout the embryonic development (Black and Waxman, 2013). Some studies reported that their expression decreases during the first weeks after birth, while others found NaV1.3 immunoreactivity in GM and/or WM of adult rat and human brain (Whitaker et al., 2001; Lindia and Abbadie, 2003; Thimmapaya et al., 2005; Cheah et al., 2013). NaV1.3 channels mainly localize to the somatodendritic compartment of neurons but were also detected along the axons including myelinated fibers where they may contribute to initiation and propagation of APs (Whitaker et al., 2001; Lindia and Abbadie, 2003; Cheah et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017). In the developing brain, NaV1.3 channels regulate proliferation and migration of cortical progenitors that do not fire APs (Smith et al., 2018).

Glia

The mRNA and NaV1.3 protein were detected in astrocytes (Black et al., 1995). RNA-seq demonstrated SCN3A expression in oligodendroglial cells and suggested higher expression in OPCs vs. mature oligodendrocytes (Larson et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2016). NaV1.3 expression in microglia was negligible or absent (Black et al., 2009; Hammond et al., 2019). Heterogeneous expression (from weak to strong) of NaV1.3 mRNA occurred in human astrocytoma, oligodendroglial tumors, and glioblastoma (Schrey et al., 2002). Functions of NaV1.3 channels in glia remain unknown.

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk mRNA-seq reported upregulation of SCN3A gene in the CA lesions (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020). The snRNA-seq found significant SCN3A expression in neuronal and OPCs clusters (Jakel et al., 2019; Tables 1, ,2).2). SCN3A upregulation during MS may reflect augmented expression of NaV1.3 protein in axons that is necessary for supporting/re-establishment of AP propagation in injured WM, because increased NaV1.3 levels are known to be associated with higher neuronal firing. For instance, mRNA and NaV1.3 protein were upregulated in spontaneously epileptic rats (Guo et al., 2008), and expression in hippocampal neurons of a novel coding variant SCN3A-K354Q resulted in enhanced Nav1.3 currents, spontaneous firing, and paroxysmal depolarizing shift-like depolarizations of the membrane potential (Estacion et al., 2010).

NaV1.6 (SCN8A)

Neurons

NaV1.6 channels cluster at high-density at the AIS and nodes of Ranvier of GM and WM axons, but can be also located on the soma, dendrites, and synapses although at a lower density (Caldwell et al., 2000; Dumenieu et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; Eshed-Eisenbach and Peles, 2020). The expression level of NaV1.6 channels is low during development, but significantly increases as the nervous system matures (Boiko et al., 2001; Osorio et al., 2005; Dumenieu et al., 2017). In the adult CNS, NaV1.6 channels are the major Na+ channels responsible for initiation and propagation of APs (Boiko et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2009). Loss of Nav1.6 activity results in decreased neuronal excitability, while gain-of-function mutations potentiate excitability (O'Brien and Meisler, 2013). SCN8A mutations in mice result in ataxia, tremor, and dystonia; in humans, SCN8A haploinsufficiency is associated with intellectual disability, while hyperactivity can contribute to pathogenesis of epileptic encephalopathy (O'Brien and Meisler, 2013; Meisler, 2019).

Glia

RNA-seq detected SCN8A transcripts in mouse oligodendrocyte lineage (Marques et al., 2016), but they were negligible in microglia (Hammond et al., 2019). Immunoreactivity for NaV1.6 was observed in cultured spinal cord astrocytes and in brain microglia in vitro and in situ (Reese and Caldwell, 1999; Black et al., 2009; Black and Waxman, 2012; Hossain et al., 2013), but their functional role is unknown.

Expression and Function in MS

Bulk mRNA-seq found upregulation of SCN8A gene in CA lesions (Elkjaer et al., 2019; Frisch et al., 2020), while snRNA-seq did not detect SCN8A transcripts (Jakel et al., 2019) (Tables 1, ,2).2). Upregulation of SCN8A may reflect increased diffuse distribution of the channels along the demyelinated axons; it may be important for remyelination but may also contribute to axonal damage. Re-distribution of NaV1.6 channels, in parallel to their loss from the nodes of Ranvier, was reported previously in chronic, active, and inactive MS plaques within cerebral hemisphere, cerebellum, and spinal cord WM tissue from MS patients (Craner et al., 2004b; Black et al., 2007; Howell et al., 2010; Bouafia et al., 2014), as well as in several CNS regions affected by demyelination in animal models, including optic nerve and spinal cord WM (Craner et al., 2003, 2004a,b; Hassen et al., 2008; Howell et al., 2010). Expression of NaV1.6 channels is disrupted at the nodes of Ranvier of WM axons in Shiverer mice that lack compact myelin (Boiko et al., 2001, 2003), and in transgenic mice overexpressing proteolipid protein that initially have normal myelination but then lose myelin (Rasband et al., 2003). During EAE in animals, NaV1.6 co-localizes with NCX and may contribute to persistent Na+ influx, increased Na+ level in the axoplasm, reversal of NCX, and intra-axonal Ca2+ overload leading to axonal damage (Craner et al., 2004a). Interestingly, robust increase in NaV1.6 expression was detected also in microglia/macrophages and was associated with microglia activation and phagocytosis in human MS brain and in the EAE model (Craner et al., 2005). SCN8A deletion resulted in reduced inflammation and improved axonal health during EAE (Alrashdi et al., 2019). Hence, microglial NaV1.6 may contribute to the pathophysiology of MS as well, yet, snRNA-seq did not detect SCN8A in WM glia clusters (Tables 1, ,22).

NaV1.9 (SCN11A)

Neurons

Although NaV1.9 channels are mainly expressed in sensory ganglia neurons (Wang et al., 2017), NaV1.9 mRNA and/or protein were detected in soma and/or proximal processes of neurons in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, cerebellar cortex, supraoptic nucleus, and spinal cord of rodents and humans (Jeong et al., 2000; Blum et al., 2002; Subramanian et al., 2012; Wetzel et al., 2013; Black et al., 2014; Kurowski et al., 2015). Information regarding axonal labeling for NaV1.9 is lacking. NaV1.9 channels regulate excitation in hippocampal neurons in concert with BDNF and TrkB, control activity-dependent axonal elongation in spinal cord motoneurons, and mediate sustained depolarizing current upon activation of M1 muscarinic receptors in cortical neurons (Blum et al., 2002; Subramanian et al., 2012; Kurowski et al., 2015). It is uncertain whether, similar to their role in the PNS (Cummins et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2017), NaV1.9 channels contribute to the regulation of Vrest and AP threshold in the CNS neurons.

Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels (VGCCs)

The VGCCs are composed of α1-, β-, α2/δ-, and γ-subunits (Catterall, 2011; Zamponi et al., 2015). The pore-forming α1-subunit determines channel activity, whereas other subunits are auxiliary and regulate function of α1-subunit. In mammalian cells, 10 different α1-subunits, encoded by different genes, classify into three subfamilies: CaV1, CaV2, and CaV3 (Catterall, 2011; Zamponi et al., 2015; Alves et al., 2019). Depending on the pharmacological properties and activation voltage of Ca2+ currents, five different types of VGCCs are distinguished: L-type, N-type, P/Q-type, R-type, and T-type.

L-Type VGCCs

The α1-subunit of L-type VGCCs is encoded by CACNA1S (CaV1.1), CACNA1C (CaV1.2), CACNA1D (CaV1.3), or CACNA1F (CaV1.4) genes. High sensitivity to dihydropyridine modulators distinguishes L-type Ca2+ channels from other types of VGCCs. In the CNS, mainly CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 subunits are expressed (Lipscombe et al., 2004; Zamponi et al., 2015), but CaV1.1 subunit was detected in human and rat basal ganglia where it is co-expressed with RyRs in GABAergic neurons (Takahashi et al., 2003).

CaV1.2 (CACNA1C)

Neurons

CaV1.2 channels account for 89% of all Ca2+ currents mediated by L-type VGCCs in the brain (Alves et al., 2019; Enders et al., 2020). In hippocampal neurons, CaV1.2 channels localize to somatodendritic compartment being placed at synapses or extra-synaptically (Joux et al., 2001; Hoogland and Saggau, 2004; Obermair et al., 2004; Tippens et al., 2008; Ortner and Striessnig, 2016), as well as to axons and/or extrasynaptic regions of axonal terminals (Tippens et al., 2008). Within the WM, CaV1.2 channels were identified in the developing rat pioneer axons and the follower axons projecting through the optic nerve, corpus callosum, anterior commissure, lateral olfactory tract, corticofugal fibers, thalamocortical axons, and the spinal cord (Ouardouz et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2012).

CaV1.2 channels open upon membrane depolarization beyond −30 mV, and mediate direct Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space into the cytoplasm. In addition, they may act as voltage sensors, transducing membrane depolarization to the RyRs activation and subsequent Ca2+ release from the ER via the mechanism of Ca2+−induced Ca2+ release (CICR) (Ouardouz et al., 2003; Micu et al., 2016; Vierra et al., 2019). Clustering and functional coupling of plasmalemmal CaV1.2 channels to RyRs of the ER is mediated by the KV2.1 channels (Vierra et al., 2019).

Neuronal CaV1.2 channels are involved in synaptic modulation, propagation of dendritic Ca2+ spikes, regulation of glutamate receptor trafficking, CREB phosphorylation, coupling of excitation to nuclear gene transcription, modulation of long-term potentiation, spatial learning, and fear response (Hofmann et al., 2014; Hopp, 2021). During brain development, spontaneous Ca2+ transients mediated by CaV1.2 channels regulate neurite growth and axonal pathfinding (Huang et al., 2012; Kamijo et al., 2018). Genetic variations in CACNA1C gene are associated with Timothy syndrome, Brugada syndrome, epilepsy, depression, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorders (Bhat et al., 2012; Bozarth et al., 2018).

Glia

CaV1.2 channels are expressed in cultured astrocytes and mediate Ca2+ transients upon direct Ca2+ entry and/or subsequent activation of RyRs (D'Ascenzo et al., 2004; Du et al., 2014; Cheli et al., 2016b). Ultrastructural studies found CaV1.2 proteins also in hippocampal astrocytes (Tippens et al., 2008). In vitro, CaV1.2 channels contribute to the mechanism of astrogliosis (Du et al., 2014; Cheli et al., 2016b), and in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, they were detected in reactive astrocyte associated with Aβ-positive plaques (Willis et al., 2010; Daschil et al., 2013).