Abstract

Free full text

Citizenship and Health Insurance Status Predict Glycemic Management: NHANES Data 2007-2016

Abstract

The prevalence of diabetes in United States (US) immigrants is higher than the general population. Non-citizenship and lack of health insurance have been associated with increased health risks including diabetes, but previous US studies were done in nonrepresentative samples and did not examine the effect on glycemic management. The purpose of this study was to compare demographic, metabolic, and behavioral risk factors for increased blood glucose including citizenship and health insurance status, and determine predictors of poor glycemic management (A1C ≥ 8.0%). Logistic regression was used to analyze data from the 2007–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) of persons with diabetes and available citizenship data ages 30 to 70 years (N=2702), excluding persons with A1C < 5% and pregnant women. Results represent the weighted sample. Among participants, 92% indicated citizenship by birth (81%) or naturalization (11%). Insured rates increased from 83% to 91% between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (p < .001). Citizenship was positively associated with insurance status, higher income and education, better diet, increased smoking, and more sedentary hours (ps < .05). Non- citizens (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.20–2.51) and uninsured persons (OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.53–2.59) were nearly twice as likely to have poor glycemic management than US citizens by naturalization and insured individuals respectively. We conclude that citizenship and absence of health insurance negatively impacts diabetes management. Policy decisions are needed that address primary and secondary prevention strategies for individuals without citizenship and health insurance to reduce diabetes burden in the US.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is prevalent in the United States (US), and associated with costly poor health outcomes. The global prevalence of adults living with diabetes has increased four-fold since 1980 and is higher in racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants from middle and lower income countries (Oza-Frank and Narayan, 2010). When not well managed, diabetes can lead to cardiovascular, eye, kidney, and neurovascular complications, and is the 7th leading cause of death in the US where the annual economic cost of diabetes is $327 billion (Centers for Diseaes Control and Prevention, 2020). Nearly 50% of persons with diabetes have not been diagnosed. Risk factors that contribute to undiagnosed or untreated diabetes are low income and educational levels, lack of access to health services, and lack of insurance (Fisher-Hoch et al., 2015).

Health insurance is essential for persons with diabetes to access quality care (Doucette et al., 2017). A study of 8305 persons with diabetes found those without private insurance or Medicaid were at a significantly higher risk of receiving substandard diabetes care compared to those with insurance (i.e., A1C testing, foot and eye examinations). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (2010), passed by Congress and enacted into law in 2010, expanded Medicaid in many states, supported the development of health exchanges for individual insurance to persons who were previously uninsured, and provided support for low income persons to purchase insurance. The ACA provided an estimated 20 million new persons with health insurance by 2016 with significant gains in health insurance coverage among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (Uberoi et al., 2016).

Two recent population-based studies using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data concluded more persons with diabetes had insurance coverage after implementation of the ACA (Casagrande et al., 2018; Myerson et al., 2019). Insurance coverage increased in adults under the standard age of eligibility for Medicare, men, all racial groups, persons with low incomes, and persons with diabetes who were previously undiagnosed (Myerson et al., 2019).

A large number of persons who reside in the US are not citizens. In 2017, there were an estimated 44.5 million immigrants in the US with approximately 21% arriving in 2010 or more recently (Batalova et al., 2020). Immigrants are defined as persons who move to a foreign country with the intent to take up residency. While the ACA provides a method of obtaining insurance for US citizens and permanent resident aliens, many persons are uninsured because they are not “qualified non-citizens” or have not resided in the US long enough to meet the 5-year waiting period requirement (Healthcare.gov, 2019). Previous studies suggest immigrants are particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes due to an increased risk for undiagnosed diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and poorer metabolic regulation when first diagnosed (Stoddard et al., 2010; Zallman et al., 2013). While there are data on health risk factors and immigrant status in several groups (e.g., Haitians, foreign-born Blacks, and Mexican-Americans) (Fisher-Hoch et al., 2015; Ford et al., 2016; Moise et al., 2017; Stoddard et al., 2010), previous studies were not drawn from a representative sample of persons in the US or directly evaluated the effect of both insurance and citizenship status on impaired glucose management.

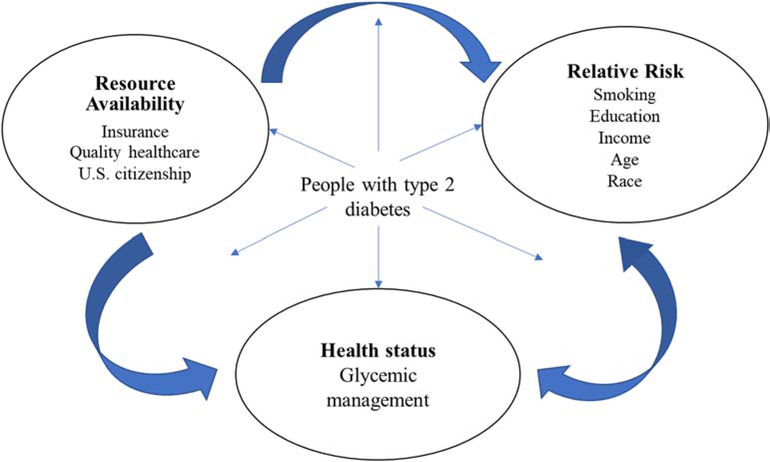

Our study examined the health outcomes of vulnerable populations such as immigrants and those without health insurance within the vulnerable populations conceptual model (VPCM) (Flaskerud and Winslow, 1998). The VPCM posits a relationship between individual relative risk and the availability of external resources to explain health morbidity and mortality. Resource availability depends on available external resources including social and economic resources, class, and access to quality healthcare. Relative risk is exposure to individual behaviors and risk factors, such as smoking, age, education, diet, and risk for diabetes. Within this framework (Figure 1), we explored both resource availability and relative risk to better understand impaired glucose management in non-citizens and the uninsured.

Predictors of Glycemic Management in U.S. Citizens and Noncitizens with Type 2 Diabetes Adapted from J. H. Flaskerud and B. J.. Winslow (1998). Conceptualizing Vulnerable Populations Health-Related Research, Nursing Research: 47 (2): 69–78.

The purpose of this study of adults with diabetes from 10 years of NHANES data was to 1) compare demographic, metabolic, and behavioral risk factors for elevated blood glucose by citizenship (citizen by birth, citizen by naturalization, or non-citizen) and health insurance status, and 2) determine variables, including citizenship and health insurance status, for models that predict poor glycemic management (A1C ≥ 8.0%).

METHODS

Design and Sample

Every two years, NHANES examines a sample with the purpose of assessing the health and nutritional status of US adults and children. Using a complex, multistage, probability sampling design to obtain a representative sample of the population, approximately 5, 000 individuals are selected. Demographic information, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related questions are collected first in the individuals’ homes then health measurements are performed in mobile centers. While the survey’s sample is selected to represent the US population of all ages, individuals who were 80 and older, African American, Asian, Hispanic, and at or below the federal poverty level were over-sampled in the surveys. Information about the NHANES design and protocol can be obtained at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx.

Data from five NHANES cohorts (2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, and 2015–2016) with continuous NHANES variables were extracted and merged. The total sample of 2702 persons met the eligibility criteria. Criteria for inclusion were ages 30 to 70 years, had diabetes, and responded with either a “yes” or “no” to the question asking about citizenship status. Persons with an A1C < 5.0% or currently pregnant women were excluded. Sample weights were used to make the sample representative of the population of the United States.

Measures

Diagnosis and severity of diabetes

Participants were categorized as having diabetes if they had either of the following criteria: 1) an affirmative answer to, “other than during pregnancy, doctor told had diabetes” or 2) if undiagnosed with diabetes, the person met the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) revised guidelines for the diagnosis of diabetes criteria (i.e., two indicators of hyperglycemia: A1C ≥ 6.5%, fasting plasma glucose of ≥ 126 mg/dL, or a 2-hour plasma glucose on the oral glucose tolerance test with a 75 gram glucose load of ≥ 200 mg/dL).(American Diabetes Association, 2019) A1C, a weighted estimate of average blood glucose over the last 3 months, was examined as both a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable as “good management” (i.e., A1C < 8.0%) or “poor management” (i.e., A1C ≥ 8.0%) (Qaseem et al., 2007). The blood glucose laboratory value was obtained after a fast of 8 to 12 hours.

Demographic and Social Determinants

Demographic variables include self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, financial status, citizenship, and insurance coverage. Participant’s age in years at the time of screening was recorded; age was treated as both a continuous variable and a dichotomous variable recoded as “30 to 49” or “50 to 70” years.

All participants were asked their sex with possible responses as “male” or “female.” Race and ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and “other or multi-racial”) was self-identified by participants. Because there was no specific designation for “Non-Hispanic Asian” included in the survey until the 2011–2012 NHANES cohort, this information was not included in the analysis. Marital status was recoded as “married/living with partner” or “single” (i.e., widowed, divorced, separated, or never married). Education was recoded as “high school graduate/GED or less” or “post high school.” Financial status was determined as the ratio of the family income to the total number of persons in the household and was calculated to compare with each cohort’s official year’s poverty index. The range of values (0 to 499%) were categorized as <150%, 150% to 299%, and 300% or higher. Participants reported their health insurance coverage (“yes” or “no”) from any source (e.g., private individual insurance, employer provided, Medicare, Medicaid, and Veteran’s Administration).

Citizenship status was categorized as citizen by birth or naturalization, and non-citizen based on questions on country of birth and citizenship status. Participants were informed that information on citizenship was for health research and would not affect pending immigration or citizenship petitions. They had the option to refuse or respond, “don’t know.” Prior to 2011, information on place of birth was delineated as “born in the 50 states or Washington, DC,” “Mexico,” “other Spanish speaking country,” or “non-Spanish speaking country.” However, since 2011 participants were only asked if they were “born in the 50 states or Washington, DC” or in “other” country. Participants not born in the US were queried on the length of time they have been in the US. If needed, an interpreter was used in the interview conducted in either English or Spanish.

Body Mass Index

Height and weight were obtained in the mobile evaluation centers. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the standard formula of weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Sedentary activity

Sedentary activity was assessed by a question about “sitting at work, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends, including time spent sitting at a desk, traveling in a car or bus, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer.” The response was categorized into two groups (less than 8 hours vs. 8 hours or more).

Nicotine use

Nicotine use was categorized as “No-nicotine” for persons who never smoked or were a former smoker, “Yes-smoker” for current smokers, and “Yes-alternatives” for persons who responded that they used a nicotine alternative (cigar smoking, chewing tobacco, snuff, or e-cigarettes). The “Yes-smoker” and “Yes-alternatives” groups were merged into a “Yes-nicotine” group.

Diet

A single question provided a subjective appraisal of diet quality. The question asks, “In general, how healthy is your diet?” with possible responses ranging on a 5-point Likert scale from “excellent” to “poor.” Diet quality was recoded as either “excellent to good” or “fair or poor.” Previous research concluded that construct validity was found high with use of this single item with much less subject burden compared to detailed food diaries (Loftfield et al., 2015).

Statistical Analysis

To estimate sampling errors based on the complex sampling design of NHANES, data analyses were conducted with the SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The dataset was weighted to adjust the unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse adjustments, and adjustments to independent population controls using the 10-year weight. Socio-demographic information was described using Surveyfreq with Wald chi-squared test (weighted % and comparisons by citizenship status and insurance status), Surveymeans (mean and standard error for continuous variables), and Surveyreg (for pairwise comparisons of continuous variables by citizenship status and insurance status). The Surveylogistic Procedures were conducted to examine predictors of poorer glycemic management (A1C ≥ 8.0% vs. A1C < 8.0%). Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were reported.

RESULTS

Description of sample

The sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics of the study’s sample of 2702 adults are depicted in Tables 1 and and2.2. Data were weighed to represent population-level representative parameters. The weighted sample was middle-aged (mean and standard error [SE] age of 55.4 ± 0.2) and distributed by sex, race, education, and marital/partnered status (47.6% female, 41.9% Non-White, 53.3% post high school education, and 65.4% married or partnered). Almost one-third of the participants were poor (< 150 of poverty index) and an additional one-fourth were working-poor with incomes of 150 to 299% of the poverty index. The majority had suboptimal glycemic management (mean A1C 7.5% ± 0.1; mean fasting blood sugar [FBS] 162.9 ± 2.2 mg/dL) were obese (mean BMI kg/m2 33.7 ± 0.3), and had risk factors for impaired metabolic regulation (24.7% reported sedentary time ≥ 8 hours/day, 35.6% reported a “fair or poor” diet, and 22.7% were current smokers/alternative nicotine users). Approximately 11% of participants did not know they had glucose levels indicative of diabetes according to the current standards.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample and Comparison by U.S. Citizenship and Health Insurance Status

| Characteristic | Total (N = 2702) | Citizen by birth (n = 1811; Weighted % = 80.9) | Citizen by Naturalization (n = 499; Weighted % = 10.7) | Non-citizen (n = 392; Weighted % = 8.4) | p-value | Health insurance (n = 2190; weighted % = 85.4) | No health insurance (n = 510; weighted % = 14.5) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, % | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

30–54 30–54 | 41.8 (1.3) | 39.9 (1.5) | 42.8 (3.1) | 59.9 (3.1) | 37.7 (1.4) | 66.7 (3.1) | ||

55–70 55–70 | 58.1 (1.3) | 60.1 (1.5) | 57.2 (3.1) | 40.1 (3.1) | 62.3 (1.4) | 33.3 (3.1) | ||

| Female, % | 47.6 (1.3) | 47.2 (1.6) | 51.4 (2.5) | 46.9 (2.7) | .433 | 47.7 (1.5) | 47.3 (2.5) | .922 |

| Race, % | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic White | 58.1 (2.4) | 69.9 (2.2) | 11.1 (2.5) | 5.5 (2.7) | 62.6 (2.2) | 32.4 (4.6) | ||

Non-Hispanic Black Non-Hispanic Black | 15.8 (1.4) | 17.4 (1.6) | 11.2 (2.1) | 5.6 (1.7) | 15.6 (1.4) | 16.8 (2.2) | ||

Hispanic Hispanic | 17.3 (1.8) | 8.2 (1.3) | 42.5 (3.9) | 73.3 (3.8) | 13.5 (1.5) | 40.0 (4.3) | ||

Other/Multi-Racial Other/Multi-Racial | 8.7 (1.0) | 4.5 (1.0) | 35.3 (3.6) | 15.6 (2.8) | 8.4 (1.1) | 10.7 (1.9) | ||

| Education, % | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

Some college or college graduate Some college or college graduate | 53.3 (1.5) | 57.3 (1.8) | 48.1 (3.3) | 21.3 (3.1) | 57.1 (1.6) | 30.9 (2.8) | ||

High school or equivalent High school or equivalent | 46.7 (1.5) | 42.8 (1.8) | 51.9 (3.3) | 78.7 (3.1) | 42.9 (1.6) | 69.1 (2.8) | ||

| Poverty level, % | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

≤ 150% ≤ 150% | 32.2 (1.4) | 28.9 (1.4) | 24.7 (1.5) | 62.0 (3.7) | 27.0 (1.5) | 63.3 (3.5) | ||

150–299% 150–299% | 24.9 (1.3) | 35.7 (3.2) | 24.6 (2.6) | 27.1 (3.0) | 24.8 (1.4) | 25.0 (2.7) | ||

≥ 300% ≥ 300% | 43.0 (1.6) | 61.9 (3.7) | 27.1 (3.0) | 11.0 (2.4) | 48.2 (1.7) | 11.7 (2.3) | ||

| Married or living with a partner, % | 65.4 (1.2) | 63.5 (1.5) | 76.4 (2.1) | 70.0 (2.5) | < .001 | 66.3 (1.2) | 60.0 (3.0) | .043 |

| Health care provider diagnosis of diabetes, % | 89.0 (0.9) | 90.0 (1.1) | 89.5 (1.5) | 78.8 (2.8) | .008 | 90.7 (0.9) | 79.2 (2.6) | < .001 |

Table 2:

Metabolic Indicators and Risk Factors for Impaired Metabolic Control of the Sample and Comparison by U.S. Citizenship and Health Insurance Status

| Characteristic | All | Citizen by birth (80.9%) | Citizen by naturalization (10.7%) | Non-citizen (8.4 %) | p-value | Health insurance (85.4%) | No health insurance (14.5%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1C (mean ± SE) | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 8.0 ± 0.2 | < .05 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | < .001 |

| FBS (mean ± SE) | 162.9 ± 2.2 | 163.8 ± 2.6 | 146.5 ± 3.6 | 175.0 ± 5.5 | < .001 | 160.7 ± 2.4 | 174.7 ± 5.3 | .018 |

| BMI (mean ± SE) | 33.7 ± 0.3 | 34.7 ± 0.2 | 30.2 ± 0.4 | 30.8 ± 0.4 | < .001 | 34.0 ± 0.2 | 33.3 ± 0.5 | .201 |

| Sedentary activity (%, SE) | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

≥ 8hrs ≥ 8hrs | 24.7 (1.3) | 27.5 (1.5) | 16.7 (2.3) | 7.7 (1.5) | 26.7 (1.5) | 13.1 (2.4) | ||

< 8hrs < 8hrs | 75.3 (1.3) | 72.5 (1.5) | 83.3 (2.3) | 92.3 (1.5) | 73.3 (1.5) | 86.9 (2.4) | ||

| Diet quality (%, SE) | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

Fair or Poor Fair or Poor | 35.6 (1.3) | 34.6 (1.6) | 32.2 (2.7) | 47.0 (2.9) | 33.6 (1.5) | 45.9 (2.8) | ||

Excellent to Good Excellent to Good | 64.6 (1.3) | 65.4 (1.6) | 67.8 (2.7) | 53.0 (2.9) | 66.4 (1.5) | 54.1 (2.8) | ||

| Nicotine status, % (SE) yes | 22.7 (1.1) | 25.1 (1.2) | 9.2 (1.8) | 17.0 (2.5) | < .001 | 21.5 (1.1) | 30.2 (2.6) | .003 |

Notes. SE = Standard Error; A1C = global glucose management; FBS = fasting blood sugar; Nicotine status, yes = persons who either responded they smoked cigarettes or used alternative nicotine products (cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff, or e-cigarettes)

More than 90% of the participants in NHANES identified themselves as citizens by birth or naturalization (91.6%) with the most stating that they were born in the US (81%). The majority of the non-citizen immigrants reported they had been in the US “more than 20 years” (66%) and about 12% had been in the US less than 10 years.

Comparison of participants by citizenship and insurance status

Tables 1 and and22 depict a comparison of the weighted percentage of participants by citizenship and insurance status. Sex did not significantly affect citizenship or insurance status. Participants who were non-citizens were significantly (p < .05) younger, non-White, without post high school education, poorer, and undiagnosed with diabetes despite having clinical data supporting the diagnosis compared to citizens by birth or naturalization (Table 1).

Overall, there were significant differences between the three groups in glycemic management, BMI, sedentary activity, dietary quality, and nicotine status (ps < .05; Table 2). Although citizens by naturalization mirrored citizens born in the US in sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, poverty level, and diet quality; ps > .05), citizens by naturalization had significantly better A1C and FBS levels and were less obese compared to native-born citizens (ps < .05). When evaluated, non-citizens had worse glucose management (A1C 8.0% vs. 7.5%, p = .005; FBS 175.5 mg/dL vs. 161.7 mg/dL, p = .034) compared to citizens by birth or naturalization despite being less obese, more active, and less likely to be current smokers/alternative nicotine users.

There was a significant increase in the percentage of NHANES participants with health insurance coverage in the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 cohorts (87.5% and 90.7%, respectively, p < .001) compared to the earlier cohorts. Citizens by birth reported a slightly higher insurance coverage than naturalized citizens (p = .042). While non-citizens were significantly less likely to have insurance compared to citizens (OR: 8.45, 95% CI: 6.12–11.67), the rate of non-citizens without insurance decreased from 61% to 40% from the earlier cohorts (2007–2008) to those cohorts after 2013 (2013–2014 and 2015–2016). Participants without insurance were significantly (p < .05) younger, non-White, without post high school education, poor, unmarried, and undiagnosed with diabetes. When evaluated, persons without insurance had worse glucose management (A1C 8.0% vs. 7.4%, p < .001; FBS 174.7 mg/dL vs.160.7 mg/dL; p = .018) compared to those with health insurance. Persons with no insurance had several behavioral risk factors for impaired metabolic regulation. They were more likely to smoke or use alternative nicotine and have a “fair or poor” diet (30.2% vs. 21.5%, p = .003 and 45.9% vs. 33.6%, p < .001), but were less likely to spend greater than 8 hours a day in sedentary activity (86.9% vs. 73.3%, p < .001).

Predictors of poor glycemic management (A1C ≥ 8.0%)

Based on the univariate analyses, citizens by naturalization (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.49–2.55) and non-citizens (OR: 5.16, 95% CI: 3.77–7.07) had a greater risk for poor glycemic management than citizens by birth. Having no health insurance (compared to having health insurance) predicted poorer glycemic management (OR: 4.75, 95% CI: 3.73–6.04). Other predictors of poorer glycemic management based on the univariate analyses included younger age, minority, less education, poorer diet, nicotine use, lower income, not being married or partnered, and sedentary activity ≥ 8 hours/day (Table 3).

Table 3:

Predictors of Poorer Glycemic Control (A1C ≥ 8.0%) among Adults with Diabetes

| Predictor | Unadjusted (Crude) OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen by naturalization vs. Citizen by birth | 1.95 | 1.49, 2.55 | 1.05 | 0.70, 1.57 |

| Noncitizen vs. Citizen by birth | 5.16 | 3.77, 7.07 | 1.74 | 1.20, 2.51 |

| No health insurance vs. Yes health insurance | 4.75 | 3.73, 6.04 | 1.99 | 1.53, 2.59 |

| Age 55–70 vs. 30–54 | 0.51 | 0.43, 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.59, 1.01 |

| Male vs. Female | 1.08 | 0.93, 1.25 | 1.20 | 0.96, 1.50 |

| Non-Hispanic Black vs. Non-Hispanic White | 2.36 | 1.78, 3.14 | 1.49 | 1.13, 1.97 |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic White | 2.96 | 2.29, 3.82 | 1.59 | 1.14, 2.22 |

| Other race vs. Non-Hispanic White | 3.48 | 2.48, 4.91 | 1.29 | 0.75, 2.23 |

| High school/GED or less vs. Post high school | 1.26 | 1.02, 1.54 | 0.93 | 0.71, 1.23 |

| Fair or poor diet vs Excellent to good diet | 2.50 | 2.07, 3.01 | 1.71 | 1.36, 2.15 |

| Nicotine use vs. No nicotine use | 3.28 | 2.55, 4.22 | 1.56 | 1.17, 2.08 |

| Poverty <150 vs. ≥ 300% | 1.65 | 1.27, 2.16 | 0.96 | 0.69, 1.33 |

| Poverty 150–299 vs. ≥ 300% | 1.63 | 1.25, 2.13 | 0.97 | 0.70, 1.34 |

| Single, divorced, or widowed vs. Married or partnered | 1.79 | 1.48, 2.16 | 1.04 | 0.84, 1.29 |

| Sedentary activity ≥ 8 vs. < 8 hours | 2.89 | 2.26, 3.69 | 1.76 | 1.31, 2.37 |

Notes. The unadjusted odd ratio (OR) represents the univariate association between the predictor and poor glycemic control. In the adjusted model, each predictor was controlled for all the other variables. CI = Confidence Interval. GED = General Education Diploma.

After controlling for covariates, non-citizens were almost 75% more likely to have an A1C ≥ 8.0% than US citizens by birth (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.20–2.51), but there was no significant difference between citizens by naturalization and citizens by birth in predicting poorer glycemic management. In the same model, individuals without health insurance were almost twice as likely (OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.53–2.59) to have A1C ≥ 8.0% than insured individuals. Low income was not significant in predicting impaired glucose management. Significant predictors for poorer glycemic management in the model were: Non-Hispanic Black vs. Non-Hispanic White (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.13–1.97); Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic White (OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.14–2.22); fair to poor diet vs. excellent to good diet (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.17–2.08); yes-nicotine vs. no-nicotine use (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.17–2.08); and sedentary activity ≥ 8 vs. < 8 hours (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.31–2.37). See Table 3 for details.

DISCUSSION

Our study expands upon findings from previous analyses of NHANES data (Kazemian et al., 2019) by examining the contribution of multiple risk factors for impaired glucose management (i.e., demographic, metabolic, behavioral, citizenship and health insurance status) in tandem. Our finding that the lack of health insurance is the strongest predictor of poor glucose management is consistent with recent analyses by Kazemian and colleagues (Kazemian et al., 2019) and emphasizes the importance of universal coverage.

Our results suggest that citizenship, by birth or naturalization, is associated with improved health outcomes including the diagnosis of diabetes, a crucial factor for the initiation of treatment. There was no significant difference in BMI between citizens by naturalization and non-citizens and FBS levels between citizens by birth and non-citizens. However, citizens by naturalization had better A1C and FBS levels, weighed less, were more active, and less likely to use nicotine than citizens by birth and non-citizens: all of which contribute to improved glucose management. The results add to our understanding that the lack of health insurance, often accompanied by lack of citizenship or immigrant status (e.g., citizenship by naturalization), predicts an increased risk of poor glycemic management while controlling for traditional risk and protective factors.

Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that although 60% of non-citizens are lawfully in the US and eligible for healthcare programs, 24% of eligible adults and 47% of undocumented immigrants remain uninsured compared to 10% of citizens (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). The rate of non-citizens without insurance decreased from 61% to 40% from 2013 to 2017, suggesting that the ACA has made a positive effect on the rate of insured immigrants (Batalova et al., 2020). Reasons listed for lack of insurance in those immigrants who are eligible include fear and confusion over enrollment for ACA insurance plans, language barriers, and limited literacy (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). More recently, fear of an adverse impact on permanent residency status may act as a barrier to persons applying for public health services (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or “food stamps”, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program) because of a change to the policies used to determine entry into the US or obtain legal permanent residency status (i.e., “green card”) to make ineligible persons who require public assistance (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019).

Vulnerable populations are defined as being at higher risk for worse health and higher rates of morbidity and mortality than the general population as a whole. In this study, the VPCM model provides explanation for our findings in that limited resource availability including non-citizenship status, and/or a lack of health insurance, lead to worse diabetes outcomes. Our data showed that socio-demographic factors of non-White race, low income, less education, and younger age predicted worse diabetes outcomes. Altogether, a lack of resources that included no access to health insurance as well as other behavioral and individual risk factors contributed to higher morbidity (worse diabetes outcomes).

Most research suggests that increased obesity, more time in sedentary activity, and nicotine use worsens glucose management. However, our data suggested that while non-citizens are less obese, more active, and were less likely to use nicotine, these health behaviors are not adequate to reduce their risk of poor glucose management secondary to lack of health insurance. In our analysis, naturalized citizens maintain these positive health behaviors and possibly with the addition of improved diet, insurance, and access to health providers for diagnosis, diabetes care and self-management education, have an equal risk of impaired glycemic regulation with citizens by birth.

Previous studies examined NHANES data from 2005–2016 regarding trends in insurance coverage and achievement of treatment goals among people with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes (Kazemian et al., 2019). Despite the decline in uninsured rates among people with undiagnosed diabetes following the ACA (Uberoi et al., 2016), gaps in diabetes care that affect achievement of treatment targets persist particularly among women, younger adults and non-white individuals (Kazemian et al., 2019). Our study corroborates many of these findings and expands this knowledge by examining citizenship status as a unique contributor to a pattern that links health insurance and glycemic outcomes.

Limitations

The limitations to this study are inherent to the use of secondary data where no causal inferences can be made because of the cross-sectional observational design and all the variables are predetermined. Unfortunately, there is no information in NHANES on whether participants have type 1, type 2, or another type of diabetes. Historical changes in the methods used to diagnose diabetes may have resulted in under-diagnosis in cohorts prior to 2010 when the ADA revised the criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes to include an A1C ≥ 6.5%. Self-report, used to determine behavioral risk factors for impaired blood glucose such as diet quality, sedentary activity, and cigarette smoking or alternative forms of nicotine use such as e-cigarettes, may be inaccurate. However, strengths of NHANES are that it is a long-running study with a large sample representative of the US population with the inclusion of multiple questionnaires and objective physiological data, and a refined protocol that maintains data collection integrity.

CONCLUSION

Impaired glucose management in persons with diabetes is known to be associated with an increased risk for health complications that negatively affect the quality of life for the individual and increase the health cost to the nation. Individual risk factors, such as age and racial/ethnic background while non-modifiable, can be addressed by increased attention to screening for diabetes. Behavioral risk factors such as obesity, diet, exercise, and smoking cessation have traditionally been the primary targets for interventions. However, the lack of health insurance is a systematic barrier for citizens that were especially onerous for non-citizen residents. We conclude that access to health care and health insurance coverage are important factors that require being addressed with policy level interventions to prevent suboptimal diabetes care, prevent complications related to poorly managed diabetes, and improve the health of the nation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K24 NR016685: Chasens).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 42 U.S.C. § 18001

- American Diabetes Association, 2019. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42, S13–S28. 10.2337/dc19-S002. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Batalova J, Blizzard B, Bolter J, 2020. Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states

- Casagrande SS, McEwen LN, Herman WH, 2018. Changes in health insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act: A national sample of U.S. adults with diabetes, 2009 and 2016. Diabetes Care 41, 956–62. 10.2337/dc17-2524. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Diseaes Control and Prevention, 2020. National diabetes statistics report. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html

- Doucette ED, Salas J, Wang J, Scherrer JF, 2017. Insurance coverage and diabetes quality indicators among patients with diabetes in the US general population. Prim Care Diabetes 11, 515–21. 10.1016/j.pcd.2017.05.007. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher-Hoch SP, Vatcheva KP, Rahbar MH, McCormick JB, 2015. Undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes in health disparities. PLoS One 10, e0133135 10.1371/journal.pone.0133135. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ, 1998. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nurs Res 47, 69–78. 10.1097/00006199-199803000-00005. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ND, Narayan KM, Mehta NK, 2016. Diabetes among US- and foreign-born blacks in the USA. Ethn Health 21, 71–84. 10.1080/13557858.2015.1010490. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare.gov, 2019. Coverage for lawfully present immigrants. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states

- Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019. Changes to “public charge” inadmissibility rule: Implications for health and health coverage. Available from: https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

- Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. Health coverage of immigrants. Available from: https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

- Kazemian P, Shebl FM, McCann N, Walensky RP, Wexler DJ, 2019. Evaluation of the cascade of diabetes care in the United States, 2005–2016. JAMA Intern Med. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Loftfield E, Yi S, Immerwahr S, Eisenhower D, 2015. Construct validity of a single-item, self-rated question of diet quality. J Nutr Educ Behav 47, 181–7. 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.09.003. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moise RK, Conserve DF, Elewonibi B, Francis LA, BeLue R, 2017. Diabetes knowledge, management, and prevention among Haitian immigrants in Philadelphia. Diabetes Educ 43, 341–47. 10.1177/0145721717715418. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson R, Romley J, Chiou T, Peters AL, Goldman D, 2019. The Affordable Care Act and health insurance coverage among people with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 42, e179–e80. 10.2337/dc19-0081. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oza-Frank R, Narayan KM, 2010. Overweight and diabetes prevalence among US immigrants. Am J Public Health 100, 661–8. 10.2105/ajph.2008.149492. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem A, Vijan S, Snow V, Cross JT, Weiss KB, Owens DK, 2007. Glycemic control and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the optimal hemoglobin A1c targets. A guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 147, 417–22. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00012. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard P, He G, Vijayaraghavan M, Schillinger D, 2010. Disparities in undiagnosed diabetes among United States-Mexico border populations. Rev Panam Salud Publica 28, 198–206. 10.1590/s1020-49892010000900010. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E, 2016. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010–2016. ASPE Issue Brief. Available from: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101701796 [Google Scholar]

- Zallman L, Himmelstein DH, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, Ayanian JZ, Wilper AP, McCormick D, 2013. Undiagnosed and uncontrolled hypertension and hyperlipidemia among immigrants in the US. J Immigr Minor Health 15, 858–65. 10.1007/s10903-012-9695-2. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106180

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/108261117

Article citations

Perceived Racial/Ethnic Discrimination, Citizenship Status, and Self-Rated Health Among Immigrant Young Adults.

J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 11(5):2676-2688, 11 Aug 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37566180

Integrating NHANES and toxicity forecaster data to compare pesticide exposure and bioactivity by farmwork history and US citizenship.

J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, 34(2):208-216, 20 Jul 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37474644 | PMCID: PMC10799167

Citizenship Matters: Non-Citizen COVID-19 Mortality Disparities in New York and Los Angeles.

Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(9):5066, 21 Apr 2022

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 35564460 | PMCID: PMC9102427

Predictive Utility of Alternate Measures of Physical Activity and Diet for Overweight and Obesity in Low-Income Minority Women.

Am J Health Promot, 36(5):801-812, 02 Mar 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35081752 | PMCID: PMC9086088

Nutritional markers of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes in adults: Findings of a machine learning analysis with external validation and benchmarking.

PLoS One, 16(5):e0250832, 05 May 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 33951067 | PMCID: PMC8099133

Go to all (6) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Association of maternal characteristics with latino youth health insurance disparities in the United States: a generalized structural equation modeling approach.

BMC Public Health, 20(1):1088, 11 Jul 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 32653037 | PMCID: PMC7353771

Sources of health insurance and characteristics of the uninsured: analysis of the March 1998 Current Population Survey.

EBRI Issue Brief, (204):1-27, 01 Dec 1998

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 10345791

Association between insurance status and mortality in individuals with albuminuria: an observational cohort study.

BMC Nephrol, 17:27, 09 Mar 2016

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 26960447 | PMCID: PMC4784311

Insurance coverage and diabetes quality indicators among patients in NHANES.

Am J Manag Care, 22(7):484-490, 01 Jul 2016

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 27442204

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NINR NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: K24 NR016685

National Institutes of Health (1)

Grant ID: K24 NR016685