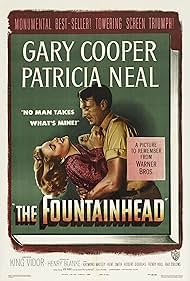

An uncompromising, visionary architect struggles to maintain his integrity and individualism despite personal, professional and economic pressures to conform to popular standards.An uncompromising, visionary architect struggles to maintain his integrity and individualism despite personal, professional and economic pressures to conform to popular standards.An uncompromising, visionary architect struggles to maintain his integrity and individualism despite personal, professional and economic pressures to conform to popular standards.

- Rally Spectator

- (uncredited)

- Courtroom Spectator

- (uncredited)

- Young Intellectual

- (uncredited)

- Prosecutor

- (uncredited)

- Female Party Guest

- (uncredited)

- Judge

- (uncredited)

- Party Guest

- (uncredited)

- Rally Spectator

- (uncredited)

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaKing Vidor originally hoped to cast Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in the lead roles, but Ayn Rand insisted on Gary Cooper in the lead. Bacall was cast opposite Cooper, but dropped out before filming began. Hoping the film would make her a star, Warner Bros cast a relative unknown, 22-year-old Patricia Neal, after considering and then rejecting Bette Davis, Ida Lupino, Alexis Smith, and Barbara Stanwyck as replacements for Bacall. Cooper objected to Neal being cast, but during filming, Cooper and Neal began an affair.

- GoofsWhen the Banner prints its front page story "The Truth about Howard Roark", a six-paragraph story is shown, but the first three paragraphs of the story are exactly the same as the last three paragraphs.

- Quotes

Howard Roark: [delivering the closing statements of his own defense] Thousands of years ago the first man discovered how to make fire. He was probably burned at the stake he had taught his brothers to light, but he left them a gift they had not conceived of, and he lifted darkness off the earth. Through out the centuries there were men who took first steps down new roads, armed with nothing but their own vision. The great creators, the thinkers, the artists, the scientists, the inventors, stood alone against the men of their time. Every new thought was opposed. Every new invention was denounced. But the men of unborrowed vision went ahead. They fought, they suffered, and they paid - but they won.

Howard Roark: No creator was prompted by a desire to please his brothers. His brothers hated the gift he offered. His truth was his only motive. His work was his only goal. His work, not those who used it, his creation, not the benefits others derived from it. The creation which gave form to his truth. He held his truth above all things, and against all men. He went ahead whether others agreed with him or not. With his integrity as his only banner. He served nothing, and no one. He lived for himself. And only by living for himself was he able to achieve the things which are the glory of mankind. Such is the nature of achievement.

Howard Roark: Man cannot survive except through his mind. He comes on earth unarmed. His brain is his only weapon. But the mind is an attribute of the individual, there is no such thing as a collective brain. The man who thinks must think and act on his own. The reasoning mind cannot work under any form of compulsion. It cannot not be subordinated to the needs, opinions, or wishes of others. It is not an object of sacrifice.

Howard Roark: The creator stands on his own judgment. The parasite follows the opinions of others. The creator thinks, the parasite copies. The creator produces, the parasite loots. The creator's concern is the conquest of nature - the parasite's concern is the conquest of men. The creator requires independence, he neither serves nor rules. He deals with men by free exchange and voluntary choice. The parasite seeks power, he wants to bind all men together in common action and common slavery. He claims that man is only a tool for the use of others. That he must think as they think, act as they act, and live is selfless, joyless servitude to any need but his own. Look at history. Everything thing we have, every great achievement has come from the independent work of some independent mind. Every horror and destruction came from attempts to force men into a herd of brainless, soulless robots. Without personal rights, without personal ambition, without will, hope, or dignity. It is an ancient conflict. It has another name: the individual against the collective.

Howard Roark: Our country, the noblest country in the history of men, was based on the principle of individualism. The principle of man's inalienable rights. It was a country where a man was free to seek his own happiness, to gain and produce, not to give up and renounce. To prosper, not to starve. To achieve, not to plunder. To hold as his highest possession a sense of his personal value. And as his highest virtue, his self respect. Look at the results. That is what the collectivists are now asking you to destroy, as much of the earth has been destroyed.

Howard Roark: I am an architect. I know what is to come by the principle on which it is built. We are approaching a world in which I cannot permit myself to live. My ideas are my property. They were taken from me by force, by breach of contract. No appeal was left to me. It was believed that my work belonged to others, to do with as they pleased. They had a claim upon me without my consent. That is was my duty to serve them without choice or reward. Now you know why I dynamited Cortlandt. I designed Cortlandt, I made it possible, I destroyed it. I agreed to design it for the purpose of seeing it built as I wished. That was the price I set for my work. I was not paid. My building was disfigured at the whim of others who took all the benefits of my work and gave me nothing in return. I came here to say that I do not recognize anyone's right to one minute of my life. Nor to any part of my energy, nor to any achievement of mine. No matter who makes the claim. It had to be said. The world is perishing from an orgy of self-sacrificing. I came here to be heard. In the name of every man of independence still left in the world. I wanted to state my terms. I do not care to work or live on any others. My terms are a man's right to exist for his own sake.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Hollywood Mavericks (1990)

Since Rand adapted the movie herself, one might have hoped for more. Rand knew how to condense her novel, but her sense of dialogue, as in her novels, is just weird. Although as a descriptive narrator her mastery of English (her first language was Russian) is absolutely brilliant, she always seemed to have a tin ear for idiomatic American speech. One gets that odd feeling of listening to a Greek tragedy, where every cadenced line seems to have transcendental meaning. (Listen to other women screenwriters of the day like Ruth Gordon, Dorothy Parker or Claire Booth to hear the difference.) And there is no question that adapting a novel of ideas to the demands of a movie is a daunting task. Clearly in this case it is one that Rand should have left to a more experienced and more removed screenwriter, but she was always very protective of her ideas and never really trusted them in anyone else's hands. That Rand was always so 'on message' with her script probably accounts for some of the strangeness of the movie. Nonetheless, like a bird with a broken wing, it remains a sentimental favorite for me.

In many ways the movie feels like more a reflection of Rand's personality than a dramatization of her novel. The high contrast black and white mirrors Rand's own moral absolutism as does the highly stylized dialogue. Even Franz Waxman's wonderful score seems to reflect the 'take no prisoners' atmosphere of the script. Patricia Neal's Dominique seems the complete overwrought personification of 'myself in a bad mood' as Rand once described the character. The operatic gestures, the turning on a heel exits, the intellectual one-liner put-downs, the moral outrage are all vintage Rand. I think it is all this that endears this movie to me, despite its numerous flaws.

And flaws there are. Both Cooper and Massey are too old for their parts. Rand was insistent on Cooper despite everything, even when it was obvious to her that he just didn't get her philosophy and was unable to deliver her message in an emotionally or dramatically meaningful way. Robert Douglas' Toohey is much too strong for the rest of the cast (though a tribute to this fine actor's skill). Rand had wanted Clifton Webb for the part, but the studio was afraid the role would tarnish his cranky heart-of-gold Mr. Belvedere image. (To see what his Toohey might have been like check out his performance as Elliott Templeton in 'The Razor's Edge'.) Another choice might have been George Sanders, whose sly Addison DeWitt in 'All About Eve' gives a glimpse of what his take on Toohey might been. What the movie lacks most though is a sense of Rand's evocative, descriptive storytelling (her strongest asset), which gets replaced by her relentless, stilted (maybe even corny) dialogue (her weakest).

For those who want to see one of Rand's works done well on film, find the Italian version of 'We the Living.' Made, ironically, in Mussolini's Italy where his minions thought that it was just an attack on Russian communism (Italy's enemy at the time). Italian audiences saw right through this and realized that it was as much an attack on Mussolini's fascism as it was on communism. Once Mussolini's dim-witted stooges realized this, they immediately pulled the film. The movie itself (called 'Noi Vivi') is beautifully made, telling Rand's story in an emotionally gripping way, with the young Alida Valli and Rossano Brazzi stealing your heart.

As for 'The Fountainhead', if you're interested in the story, read the book.

If you're interested in the Rand persona, then go ahead and see the movie. Oh, see it anyway! You might find its quirky charm appealing.

- How long is The Fountainhead?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $2,375,000 (estimated)

- Runtime1 hour 54 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page