Rafael Sabatini(1875-1950)

- Writer

Rafael Sabatini was born near the Adriatic seaport of Ancona, Italy to

Anna Trafford, an Englishwoman, and Italian Vincenzo Sabatini, both of

whom were well known opera singers. With their careers still in full

swing and included much traveling, so baby Rafael was sent to her

parents near Liverpool for a stable home life. After seven years they

retired from opera and turned to being voice teachers and the boy

rejoined them, first in Portugal where they set up their first music

school, then back to Italy, where they settled in Milan.

By early adolescence Rafael had already been a voracious reader, with a particular fondness for romantic historical novels. He was schooled at Zug, Switzerland, but by 17 years of age he was well versed in some six languages and decided it was time to make his way in the world. His father stepped in and determined that Rafael's linguistic skill was best served in international commerce, so he was sent back to Liverpool in 1892--a logical decision, since he had family there and the city was Great Britain's largest commercial port. His knowledge of Portuguese came in especially useful in his company's dealings in Brazil, but after four years of business, Rafael's interest in writing was bubbling to the top. He was writing his own romance stories, which he believed to be more interesting than just reading the works of others. All of this work was in English, as he considered the best literature of the world to be in that language. Some of his work was submitted by an acquaintance to an editor and, and wound up being accepted and published by a Liverpool publisher. By 1899 he was selling short stories regularly to prominent magazines: Person's, London, and Royal. He also had a translation job as well, and by 1905 with two novels published, he decided to devote full time to writing. That same year he married Ruth Goad Dixon, the daughter of a Liverpool paper merchant. At that point Sabatini moved to London, the publishing hub of Britain.

Rafael produced, in addition to about a novel a year, a steady stream of short stories. By the time he published his first really interesting swashbuckler, "The Sea Hawk", in 1915 he had completed 12 novels and, although comfortable in his new living, he was not the success he had envisioned. Though he had a modest and loyal following and his historical research was of a high degree, Sabatini's earlier work could be rather uneven in subject matter, of special interest to him but not the public. For instance, his supposed illegitimacy may have led to his half-dozen books dealing with the illegitimate despot Cesare Borgia of early 16th-century Italy. He also sometimes hampered himself with heavy-handed historical constraints, dragged out with extraneous philosophizing, as well as stilted dialog--but some of these faults were characteristic of 19th- and early 20th-century novel writing style. He managed another novel for 1917, but through most of World War I he was working in as a translator for the British intelligence service--evidently of great import to the war effort (he had finally become a British citizen, due in no small part to Italy's continued threats to conscript him into the army).

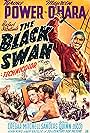

Sabatini returned to his writing after the war but nothing was forthcoming until 1921. He had been writing professionally for nearly 25 years when he finished "Scaramouche" and tried, but failed, to interest several American publishers in it. It was, however, picked up in England for publishing, and then in America as well. The story of Andre Moreau in the period of the French Revolution became a runaway best-seller internationally. After the success of "Scaramouche", Sabatini was ready with a second to his 1-2 punch. In 1922 "Captain Blood" was published, to even greater success. Suddenly his earlier works were being rushed into reprints, the most popular being "The Sea Hawk". Although the growing silent-film industry had already used six of his stories for films, they quickly started optioning the new best sellers for production. "Scaramouche" was turned into Scaramouche (1923) and followed by The Sea Hawk (1924) which hewed to the book's many turns, something the 1940 Errol Flynn version didn't do, opting for pretty much an entirely new screenplay, but was nonetheless extremely popular. The 1935 remake of "Captain Blood", also starring Flynn (Captain Blood (1935)), stuck the novel's story and was just as popular. The "Scaramouche" remake (Scaramouche (1952)) starred Stewart Granger and was a big hit.

By 1925 Sabatini had achieved his dream of success--he was rich and still filled with ideas and the will to write still more novels. There was time to rest, especially in his much beloved Wales--fishing was one of his favorite pastimes--but he also loved to ski. There was tragedy ahead, however. The Sabatinis' only son Rafael-Angelo (born in 1909 and nicknamed Binkie), busy with college, was given a new car by his parents in 1927. They were all due to go north to Scotland for a vacation, when the son and his mother went for a drive and the car was involved in an accident. Ruth Sabatini was thrown from the vehicle and knocked unconscious and was unable to remember what had happened, but Rafael-Angelo was fatally injured. Sabatini, returning from taking a friend to the railway station in Gloucester, happened on the accident and found his wife and son lying by the side of the road. The son died after arrival back at their rented estate of Brockweir House. The parents were devastated, and Sabatini went into a depression that stopped all writing. He started again a year later, and it would provide him enough to enable him to complete another novel, "The Hounds of God". Thereafter the novel-a-year work ethic would continue until 1941. However, his relationship with his wife was already strained by the time of their son's death, and they divorced in 1931. That year he also did a sequel to "Scaramouche"--"Scaramouche the Kingmaker". Sabatini turned to a new domesticated tranquility, having finally moved to Wales near Hay-on-Wye and refurbishing a fine old home called Clock Mill, complete with its own stream and stocked with trout.

In 1935 he married the sculptress Christine Goad, the wife of his first wife's brother. They were a happy couple, spending each January in Adelboden, Switzerland, for skiing. He finished a two-volume set of stories centering on his Captain Blood character called "Chivalry" in 1935. By the late 1930s the clouds of war in Europe especially disturbed Sabatini. He suffered through yet another tragedy when his new wife's son, Lancelot, flew over their house the day he received his RAF pilot's wings. The plane went out of control and crashed in flames across the Wye in a field right before their eyes. Sabatini wrote no more novels until 1944, for by this time he was developing what appeared to be stomach cancer. He managed one more novel in 1949, his 31st. He died on one last trip to Adelboden in 1950 and was buried there. On his headstone his wife had written the first lines from Scaramouche: "He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad." It made a very fitting epitaph. There have been 21 adaptations of his works for the screen, both in film and on TV. His writings also included eight collections of short novels/stories, six non-fiction books and many short stories, some of which are lost.

By early adolescence Rafael had already been a voracious reader, with a particular fondness for romantic historical novels. He was schooled at Zug, Switzerland, but by 17 years of age he was well versed in some six languages and decided it was time to make his way in the world. His father stepped in and determined that Rafael's linguistic skill was best served in international commerce, so he was sent back to Liverpool in 1892--a logical decision, since he had family there and the city was Great Britain's largest commercial port. His knowledge of Portuguese came in especially useful in his company's dealings in Brazil, but after four years of business, Rafael's interest in writing was bubbling to the top. He was writing his own romance stories, which he believed to be more interesting than just reading the works of others. All of this work was in English, as he considered the best literature of the world to be in that language. Some of his work was submitted by an acquaintance to an editor and, and wound up being accepted and published by a Liverpool publisher. By 1899 he was selling short stories regularly to prominent magazines: Person's, London, and Royal. He also had a translation job as well, and by 1905 with two novels published, he decided to devote full time to writing. That same year he married Ruth Goad Dixon, the daughter of a Liverpool paper merchant. At that point Sabatini moved to London, the publishing hub of Britain.

Rafael produced, in addition to about a novel a year, a steady stream of short stories. By the time he published his first really interesting swashbuckler, "The Sea Hawk", in 1915 he had completed 12 novels and, although comfortable in his new living, he was not the success he had envisioned. Though he had a modest and loyal following and his historical research was of a high degree, Sabatini's earlier work could be rather uneven in subject matter, of special interest to him but not the public. For instance, his supposed illegitimacy may have led to his half-dozen books dealing with the illegitimate despot Cesare Borgia of early 16th-century Italy. He also sometimes hampered himself with heavy-handed historical constraints, dragged out with extraneous philosophizing, as well as stilted dialog--but some of these faults were characteristic of 19th- and early 20th-century novel writing style. He managed another novel for 1917, but through most of World War I he was working in as a translator for the British intelligence service--evidently of great import to the war effort (he had finally become a British citizen, due in no small part to Italy's continued threats to conscript him into the army).

Sabatini returned to his writing after the war but nothing was forthcoming until 1921. He had been writing professionally for nearly 25 years when he finished "Scaramouche" and tried, but failed, to interest several American publishers in it. It was, however, picked up in England for publishing, and then in America as well. The story of Andre Moreau in the period of the French Revolution became a runaway best-seller internationally. After the success of "Scaramouche", Sabatini was ready with a second to his 1-2 punch. In 1922 "Captain Blood" was published, to even greater success. Suddenly his earlier works were being rushed into reprints, the most popular being "The Sea Hawk". Although the growing silent-film industry had already used six of his stories for films, they quickly started optioning the new best sellers for production. "Scaramouche" was turned into Scaramouche (1923) and followed by The Sea Hawk (1924) which hewed to the book's many turns, something the 1940 Errol Flynn version didn't do, opting for pretty much an entirely new screenplay, but was nonetheless extremely popular. The 1935 remake of "Captain Blood", also starring Flynn (Captain Blood (1935)), stuck the novel's story and was just as popular. The "Scaramouche" remake (Scaramouche (1952)) starred Stewart Granger and was a big hit.

By 1925 Sabatini had achieved his dream of success--he was rich and still filled with ideas and the will to write still more novels. There was time to rest, especially in his much beloved Wales--fishing was one of his favorite pastimes--but he also loved to ski. There was tragedy ahead, however. The Sabatinis' only son Rafael-Angelo (born in 1909 and nicknamed Binkie), busy with college, was given a new car by his parents in 1927. They were all due to go north to Scotland for a vacation, when the son and his mother went for a drive and the car was involved in an accident. Ruth Sabatini was thrown from the vehicle and knocked unconscious and was unable to remember what had happened, but Rafael-Angelo was fatally injured. Sabatini, returning from taking a friend to the railway station in Gloucester, happened on the accident and found his wife and son lying by the side of the road. The son died after arrival back at their rented estate of Brockweir House. The parents were devastated, and Sabatini went into a depression that stopped all writing. He started again a year later, and it would provide him enough to enable him to complete another novel, "The Hounds of God". Thereafter the novel-a-year work ethic would continue until 1941. However, his relationship with his wife was already strained by the time of their son's death, and they divorced in 1931. That year he also did a sequel to "Scaramouche"--"Scaramouche the Kingmaker". Sabatini turned to a new domesticated tranquility, having finally moved to Wales near Hay-on-Wye and refurbishing a fine old home called Clock Mill, complete with its own stream and stocked with trout.

In 1935 he married the sculptress Christine Goad, the wife of his first wife's brother. They were a happy couple, spending each January in Adelboden, Switzerland, for skiing. He finished a two-volume set of stories centering on his Captain Blood character called "Chivalry" in 1935. By the late 1930s the clouds of war in Europe especially disturbed Sabatini. He suffered through yet another tragedy when his new wife's son, Lancelot, flew over their house the day he received his RAF pilot's wings. The plane went out of control and crashed in flames across the Wye in a field right before their eyes. Sabatini wrote no more novels until 1944, for by this time he was developing what appeared to be stomach cancer. He managed one more novel in 1949, his 31st. He died on one last trip to Adelboden in 1950 and was buried there. On his headstone his wife had written the first lines from Scaramouche: "He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad." It made a very fitting epitaph. There have been 21 adaptations of his works for the screen, both in film and on TV. His writings also included eight collections of short novels/stories, six non-fiction books and many short stories, some of which are lost.