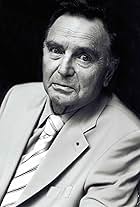

Charles Rosher(1885-1974)

- Cinematographer

- Camera and Electrical Department

- Additional Crew

Among the foremost technical innovators in his field, a charter member

of the American Society of Cinematographers, English-born Charles

Rosher had initially aimed for a diplomatic career. Fortunately, he

chose a different career option and attended lessons in photography at

the London Polytechnic in Regent Street. He must have been a keen

student, for he found himself apprenticed to noted portrait

photographers David Blount and Howard Farmer, soon afterward becoming

assistant to Richard Neville Speaight (1875-1938), the official Royal

photographer. Having learned the art of still photography, Rosher

departed England for the United States sometime in late 1908, equipped

with a Williamson camera.

In 1910, Rosher found his first job in the fledgling film industry through a connection forged with an English compatriot, the pioneer producer David Horsley: as principal cameraman for Horsley's East Coast-based Centaur Film Company (which made Rosher Hollywood's first ever full-time cinematographer). Centaur was renamed Nestor Studios upon its permanent relocation to California in 1911, setting up at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. Essentially all of Rosher's early work consisted of one and two reelers, invariably made for Nestor's chief director, Al Christie. Some were comedies, many were 'quota quickie' westerns, such as The Indian Raiders (1912), for which Nestor imported genuine Indians from New Mexico.

In 1913, Rosher accompanied directors Raoul Walsh and Christy Cabanne on his famous expedition to Mexico to shoot the feature film The Life of General Villa (1914). The rebel leader Pancho Villa had agreed to grant exclusive rights to filming of his battles against the Federales by the Mutual Film Corporation, in exchange for a fee of $25,000 and 20% of all revenues from the picture. There were a number of hazards experienced by Rosher during this adventure, including capture by enemy forces, and at times coercive interference from Villa, who fancied himself as a filmmaker.

Upon his return to the other side of the border, Rosher had a brief spell with Universal (which had absorbed Nestor), followed by two years with the Lasky Feature Play Company (which later became Paramount). He then worked at United Artists from 1919 to 1928, becoming the favourite cinematographer of the company's biggest asset, Mary Pickford, lighting her in such a way that her true age never interfered with the image of the ingénue she persisted in portraying on screen. During this period, Rosher also developed his own unique visual style, which married artistry with technical know-how. He was much acclaimed for the sharpness and clarity of his photography, for the effects he achieved by combining natural and artificial light, photographing people against reflecting surfaces (glass, water), double exposure effects, split screen techniques, and so on. Rosher also patented several inventions, including a system for developing black & white film, ABC Pyro (A=pyro,B=sulfite,C=carbonate).

In 1929 Rosher became co-recipient (with Karl Struss) of the first-ever Oscar for cinematography bestowed by the Academy, for a film made at Fox: Sunrise (1927) - still regarded today as one of the finest examples of 1920's filmmaking. With its many scenes bathed in light or twilight, it has also been likened to a cinematic French impressionism. Rosher himself recalled this as one of the most difficult assignments of his career, particularly in terms of lighting such tricky scenes as the moonlit, fog-bound swamp, necessitating a very mobile camera. "Sunrise", inevitably, ended up winning the top award for 'unique and artistic production'. Two years later, after a falling out with Pickford during filming of Coquette (1929) , Rosher went his own way. He was never out of a job for long, working variously for RKO (1932-33), MGM (1930,1934) and Warner Brothers (1937-41).

Though he had made his reputation with black & white photography, Rosher easily adapted to the medium of colour. He enjoyed a major resurgence in the second half of his career, shooting some of the most sumptuous technicolor musicals (Ziegfeld Follies (1945), Show Boat (1951)) and dramas (The Yearling (1946),Scaramouche (1952)) during his tenure at MGM, which lasted from 1942 to 1954. He won his second Oscar for "Yearling" and became the only ever recipient of a fellowship by the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. Rosher retired in 1955, except for occasional lectures and guest appearances at film festivals. He settled down on a 1,600-acre plantation he had acquired at Port Antonio on Jamaica, formerly owned by Errol Flynn. He died in 1974 in Portugal, after a fall, at the respectable age of 88.

In 1910, Rosher found his first job in the fledgling film industry through a connection forged with an English compatriot, the pioneer producer David Horsley: as principal cameraman for Horsley's East Coast-based Centaur Film Company (which made Rosher Hollywood's first ever full-time cinematographer). Centaur was renamed Nestor Studios upon its permanent relocation to California in 1911, setting up at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. Essentially all of Rosher's early work consisted of one and two reelers, invariably made for Nestor's chief director, Al Christie. Some were comedies, many were 'quota quickie' westerns, such as The Indian Raiders (1912), for which Nestor imported genuine Indians from New Mexico.

In 1913, Rosher accompanied directors Raoul Walsh and Christy Cabanne on his famous expedition to Mexico to shoot the feature film The Life of General Villa (1914). The rebel leader Pancho Villa had agreed to grant exclusive rights to filming of his battles against the Federales by the Mutual Film Corporation, in exchange for a fee of $25,000 and 20% of all revenues from the picture. There were a number of hazards experienced by Rosher during this adventure, including capture by enemy forces, and at times coercive interference from Villa, who fancied himself as a filmmaker.

Upon his return to the other side of the border, Rosher had a brief spell with Universal (which had absorbed Nestor), followed by two years with the Lasky Feature Play Company (which later became Paramount). He then worked at United Artists from 1919 to 1928, becoming the favourite cinematographer of the company's biggest asset, Mary Pickford, lighting her in such a way that her true age never interfered with the image of the ingénue she persisted in portraying on screen. During this period, Rosher also developed his own unique visual style, which married artistry with technical know-how. He was much acclaimed for the sharpness and clarity of his photography, for the effects he achieved by combining natural and artificial light, photographing people against reflecting surfaces (glass, water), double exposure effects, split screen techniques, and so on. Rosher also patented several inventions, including a system for developing black & white film, ABC Pyro (A=pyro,B=sulfite,C=carbonate).

In 1929 Rosher became co-recipient (with Karl Struss) of the first-ever Oscar for cinematography bestowed by the Academy, for a film made at Fox: Sunrise (1927) - still regarded today as one of the finest examples of 1920's filmmaking. With its many scenes bathed in light or twilight, it has also been likened to a cinematic French impressionism. Rosher himself recalled this as one of the most difficult assignments of his career, particularly in terms of lighting such tricky scenes as the moonlit, fog-bound swamp, necessitating a very mobile camera. "Sunrise", inevitably, ended up winning the top award for 'unique and artistic production'. Two years later, after a falling out with Pickford during filming of Coquette (1929) , Rosher went his own way. He was never out of a job for long, working variously for RKO (1932-33), MGM (1930,1934) and Warner Brothers (1937-41).

Though he had made his reputation with black & white photography, Rosher easily adapted to the medium of colour. He enjoyed a major resurgence in the second half of his career, shooting some of the most sumptuous technicolor musicals (Ziegfeld Follies (1945), Show Boat (1951)) and dramas (The Yearling (1946),Scaramouche (1952)) during his tenure at MGM, which lasted from 1942 to 1954. He won his second Oscar for "Yearling" and became the only ever recipient of a fellowship by the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. Rosher retired in 1955, except for occasional lectures and guest appearances at film festivals. He settled down on a 1,600-acre plantation he had acquired at Port Antonio on Jamaica, formerly owned by Errol Flynn. He died in 1974 in Portugal, after a fall, at the respectable age of 88.