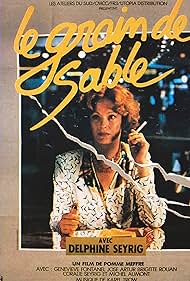

A middle-aged woman coping with an ungovernable present and holding out hopes of escaping to a more pleasant past. She leaves her current residence to retreat to her provincial French hometo... Read allA middle-aged woman coping with an ungovernable present and holding out hopes of escaping to a more pleasant past. She leaves her current residence to retreat to her provincial French hometown.A middle-aged woman coping with an ungovernable present and holding out hopes of escaping to a more pleasant past. She leaves her current residence to retreat to her provincial French hometown.

Photos

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Featured review

Solange (Delphine Seyrig) is released from her job as ticket clerk and bookkeeper for a small repertory theatre in Paris, when attendance drops and her manager is forced to close up after many years. The film is comprised of vignettes that allow us glimpses into her new life of uncertainty, a life which begins to challenge and expose her frail sense of identity, which has been dependent on work, and used in part to cover up unhappiness. The question becomes: if Solange doesn't work, who is she? A few vignettes:

A sidewalk café table. She sits looking about, preoccupied. Two younger men sit nearby, engaged in discussion. No one else is there, it is during the day when most people are at work. She looks at them, then at her folded newspaper, marks it with a pencil (classifieds), then returns it to her bag. She is looking again, at nothing in particular, becoming more still now.

The unemployment agency, where she waits in line. There is another woman behind her of similar age (mid 50s), sizing her up. Solange nervously tries to prepare for her turn at the desk. She turns once to smile at the woman, who smiles back, a moment of artificial friendliness. Once Solange turns away the woman's glowering regard resumes.

Solange walks through the streets. Paris is busy, gray, nondescript. She sits back in a lounge exhausted, alone, quiet. Outside a cinema, she watches the cashier, the customers, then hurries on. She sits on a park bench, sunbathing. She sits there in the evening, in the dark. We cannot distinguish her features.

Only one interview is shown. An empty restaurant in the afternoon. She waits until the owner arrives, smiles graciously. He asks about her bookkeeping experience. She affirms, and leaves. He turns to the barmaid, says he has already found someone else. The barmaid asks if she's experienced, he waves his hand saying, oh no, not at all, but she's young, pretty and has a dynamic personality.

Increasingly estranged, yet Solange keeps smiling. And she smiles elegantly. After all, it is Delphine Seyrig's smile.

Cafés and restaurants, where Solange has numerous encounters with younger, more attractive and enthusiastic women, who may hold uninteresting jobs they take for granted. Nonetheless they are employed. Earlier, Solange's friend and co-worker from the theatre, an attractive blond, receives warm attention from men in the café, particularly intimate attention from one. Solange excuses herself quickly, and leaves.

She is divorced and alone. A close friend is concerned, takes her shopping to buy elegantly seductive evening wear, tries to match her up, provides an arranged dinner occasion. The selected prospect is there to meet Solange, who smiles less this evening, keeps looking away. Conversation is terse, punctuated by silence.

To overcome increasing feelings of aimlessness, she attempts to bring about something new as she paints a room in her daughter's flat, something daring, a dark blue color. Her daughter suddenly arrives home, her expression of unwelcome surprise registers clearly. Solange makes a feeble remark which goes unanswered, and falls silent.

Solange in Corsica, on sun-drenched streets. She sits overlooking a pristine blue ocean, gazes at dazzling pure-white cliffs down the coast, remembers words from an unresolved love affair with a Corsican baker 20 years ago. Solange walks streets, enters bakeries, buys pastries as a pretext to ask after his whereabouts. She keeps walking, eating pastries. In the distance, a funeral procession slowly leaves a church, the bells ringing. In the distance, Solange slowly walks down a street, sun overhead, the bells ringing. In the evening, in her hotel room, she reclines, awake.

Earlier, another evening, location unclear; perhaps the hotel in Corsica or her apartment building in Paris. Solange in a stairwell hears voices above, a closing door. Huddled into a corner waiting, she takes off her shoes, moves quietly up the stairs, letting herself in to her rooms without turning on the light. Walking forward into another room, she appears to fall in the dark. She is laying face down on the bed, her wracking sobs muffled, a crying not heard in conventional films.

"Grain of Sand" was Pomme Meffre's first feature. Her economy with character exposition and mise-en-scène easily matches the apparent economy of the film's production values. Indeed there is a bareness of stylistic approach, an almost accidental quality of home-movie aesthetics, which however becomes unexpectedly synchronous with the print quality here (the Facets release). The 16mm print has scratches, specks, soft focus, washed-out colors and very apparent reel changes. Together these elements unintentionally create an overall effect of watching an archival relic, the presence of Seyrig almost spectrally creating the apparition of a final performance, elevating the degree of pathos. In short, increasing the sense that everything here, Solange especially, is only just holding together.

These qualities aside, the film should be seen for Seyrig. This was not her last role, but in watching her here there arises a sad sense that this once great actress is no longer with us. She once said that she only wanted to make films which could affect or change people.

Her Solange shares some similarities with her Jeanne Dielman, her ultimate, unique creation (for Chantal Akerman). Both are alienated older women, severely tried by negotiating days of increasingly fragile existence, and an ongoing displacement of identity. Perhaps the director had Seyrig in mind (even Jeanne Dielman) from the start; yet even if Meffre had been more forthcoming in developing Solange's character, Seyrig would still have shown us only what is important or even possible to know about Solange. This is what matters.

Especially her smile. . . elsewhere often enigmatic, but here quite tragic as it masks and evades.

A sidewalk café table. She sits looking about, preoccupied. Two younger men sit nearby, engaged in discussion. No one else is there, it is during the day when most people are at work. She looks at them, then at her folded newspaper, marks it with a pencil (classifieds), then returns it to her bag. She is looking again, at nothing in particular, becoming more still now.

The unemployment agency, where she waits in line. There is another woman behind her of similar age (mid 50s), sizing her up. Solange nervously tries to prepare for her turn at the desk. She turns once to smile at the woman, who smiles back, a moment of artificial friendliness. Once Solange turns away the woman's glowering regard resumes.

Solange walks through the streets. Paris is busy, gray, nondescript. She sits back in a lounge exhausted, alone, quiet. Outside a cinema, she watches the cashier, the customers, then hurries on. She sits on a park bench, sunbathing. She sits there in the evening, in the dark. We cannot distinguish her features.

Only one interview is shown. An empty restaurant in the afternoon. She waits until the owner arrives, smiles graciously. He asks about her bookkeeping experience. She affirms, and leaves. He turns to the barmaid, says he has already found someone else. The barmaid asks if she's experienced, he waves his hand saying, oh no, not at all, but she's young, pretty and has a dynamic personality.

Increasingly estranged, yet Solange keeps smiling. And she smiles elegantly. After all, it is Delphine Seyrig's smile.

Cafés and restaurants, where Solange has numerous encounters with younger, more attractive and enthusiastic women, who may hold uninteresting jobs they take for granted. Nonetheless they are employed. Earlier, Solange's friend and co-worker from the theatre, an attractive blond, receives warm attention from men in the café, particularly intimate attention from one. Solange excuses herself quickly, and leaves.

She is divorced and alone. A close friend is concerned, takes her shopping to buy elegantly seductive evening wear, tries to match her up, provides an arranged dinner occasion. The selected prospect is there to meet Solange, who smiles less this evening, keeps looking away. Conversation is terse, punctuated by silence.

To overcome increasing feelings of aimlessness, she attempts to bring about something new as she paints a room in her daughter's flat, something daring, a dark blue color. Her daughter suddenly arrives home, her expression of unwelcome surprise registers clearly. Solange makes a feeble remark which goes unanswered, and falls silent.

Solange in Corsica, on sun-drenched streets. She sits overlooking a pristine blue ocean, gazes at dazzling pure-white cliffs down the coast, remembers words from an unresolved love affair with a Corsican baker 20 years ago. Solange walks streets, enters bakeries, buys pastries as a pretext to ask after his whereabouts. She keeps walking, eating pastries. In the distance, a funeral procession slowly leaves a church, the bells ringing. In the distance, Solange slowly walks down a street, sun overhead, the bells ringing. In the evening, in her hotel room, she reclines, awake.

Earlier, another evening, location unclear; perhaps the hotel in Corsica or her apartment building in Paris. Solange in a stairwell hears voices above, a closing door. Huddled into a corner waiting, she takes off her shoes, moves quietly up the stairs, letting herself in to her rooms without turning on the light. Walking forward into another room, she appears to fall in the dark. She is laying face down on the bed, her wracking sobs muffled, a crying not heard in conventional films.

"Grain of Sand" was Pomme Meffre's first feature. Her economy with character exposition and mise-en-scène easily matches the apparent economy of the film's production values. Indeed there is a bareness of stylistic approach, an almost accidental quality of home-movie aesthetics, which however becomes unexpectedly synchronous with the print quality here (the Facets release). The 16mm print has scratches, specks, soft focus, washed-out colors and very apparent reel changes. Together these elements unintentionally create an overall effect of watching an archival relic, the presence of Seyrig almost spectrally creating the apparition of a final performance, elevating the degree of pathos. In short, increasing the sense that everything here, Solange especially, is only just holding together.

These qualities aside, the film should be seen for Seyrig. This was not her last role, but in watching her here there arises a sad sense that this once great actress is no longer with us. She once said that she only wanted to make films which could affect or change people.

Her Solange shares some similarities with her Jeanne Dielman, her ultimate, unique creation (for Chantal Akerman). Both are alienated older women, severely tried by negotiating days of increasingly fragile existence, and an ongoing displacement of identity. Perhaps the director had Seyrig in mind (even Jeanne Dielman) from the start; yet even if Meffre had been more forthcoming in developing Solange's character, Seyrig would still have shown us only what is important or even possible to know about Solange. This is what matters.

Especially her smile. . . elsewhere often enigmatic, but here quite tragic as it masks and evades.

- TravelerThruKalpas

- Apr 7, 2006

- Permalink

Details

- Runtime1 hour 30 minutes

- Color

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content