C4a. Status of UK priority species – Relative abundance

Type: State Indicator

This indicator was updated on 25 May 2023.

Introduction

This indicator shows changes in the relative abundance of priority species in the UK for which data are available. Priority species are defined as those appearing on one or more of the biodiversity lists of each UK country (Natural Environmental and Rural Communities Act 2006 – Section 41 (England), Environment (Wales) Act 2016 section 7, Northern Ireland Priority Species List, Scottish Biodiversity List). The combined list contains 2,890 species in total. The priority species were highlighted as being of conservation concern for a variety of reasons, including rapid decline in some of their populations. The indicator will increase when the population of priority species grows on average and decrease when the population declines.

This indicator should be read in conjunction with C4b which provides data on those UK priority species for which distribution data are available.

Key results

Official lists of priority species have been published for each UK country. There are 2,890 species on the combined list; actions to conserve them are included within the respective countries’ biodiversity or environment strategies. This indicator shows the average change in 228 species (long-term) and 215 species (short-term) for which abundance trends are available.

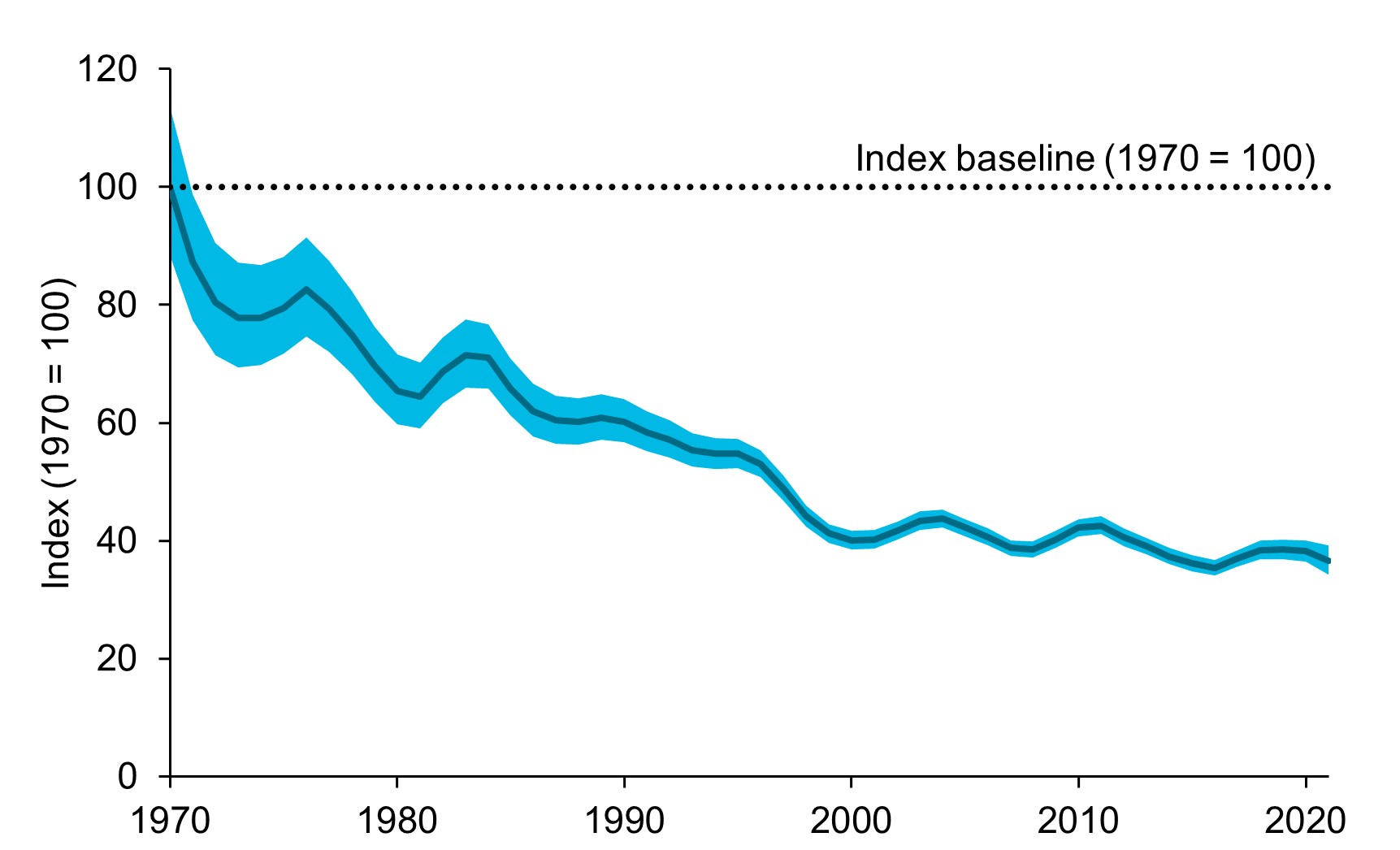

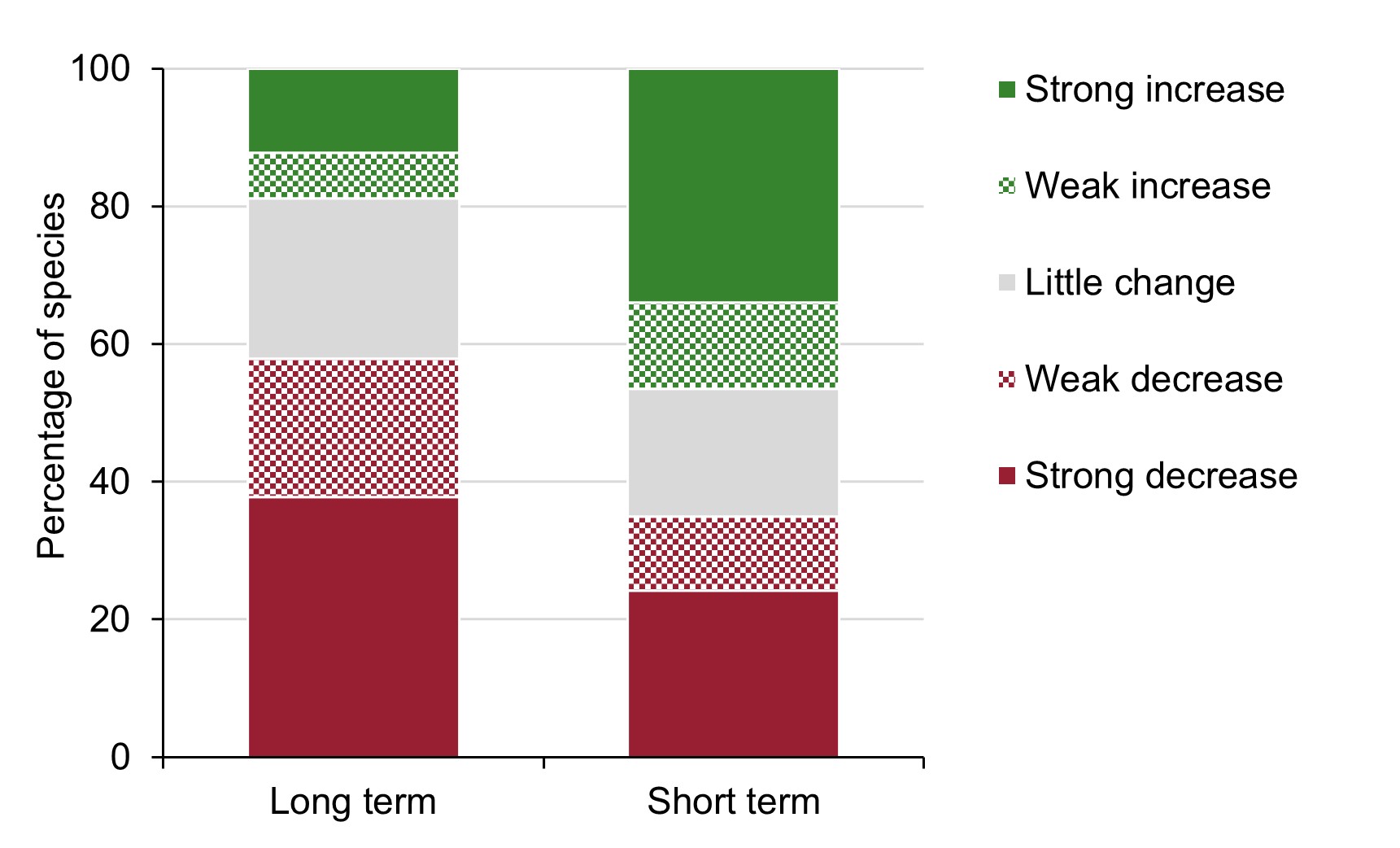

By 2021, the index of relative abundance of priority species in the UK had declined to 37% of its base-line value in 1970, a statistically significant decrease (Figure C4aia). Over this long-term period, 19% of species showed a strong or weak increase and 58% showed a strong or weak decline (Figure C4aib).

Between 2016 and 2021, the indicator did not change significantly, the 2021 value of the indicator was 1 percentage point higher than the 2016 value. Over this short-term period, 47% of species showed a strong or weak increase and 35% showed a strong or weak decline (Figure C4aib).

Figure C4aia. Trend in the relative abundance of priority species in the UK, 1970 to 2021

Figure C4aib. Long-term and short-term changes in individual species’ trends for priority species in the UK, 1970 to 2021

Notes about Figures C4aia and C4aib:

- Figure C4aia (the line graph) includes individual measures for 228 priority species and shows the smoothed trend (solid line) with its 95% credible interval (shaded area). The width of the credible interval (CI) is in part determined by the proportion of species in the indicator for which data are available; the CI narrows as data become available for groups such as bats in the 1990s and widens as datasets such as the Rothamsted Insect Survey drop out before the final indicator year.

- Figure C4aib (the bar chart) shows the percentage of species within the indicator that have increased (weakly or strongly), decreased (weakly or strongly) or shown little change in abundance based on set thresholds of change.

- All species in the indicator are present on one or more of the country priority species lists (Natural Environmental and Rural Communities Act 2006 – Section 41 (England), Environment (Wales) Act 2016 section 7, Northern Ireland Priority Species List, Scottish Biodiversity List).

- This indicator is not directly comparable with the previous publication; the number of species included in the composite index has increased from 224 in the 2021 UKBI update, to 228 in this latest update, with an additional 4 moth species added to the analysis.

Source: Bat Conservation Trust; British Trust for Ornithology; Butterfly Conservation; UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology; Defra; Joint Nature Conservation Committee; People’s Trust for Endangered Species; Rare Birds Breeding Panel; Rothamsted Research; Royal Society for the Protection of Birds; The State of Britain’s Larger Moths 2021.

Assessment of change in the relative abundance of priority species in the UK

| Long term | Short term | Latest year | |

| Priority species – Relative abundance |

Deteriorating 1970–2021 |

Little or no overall change 2016–2021 |

Decreased (2021) |

Notes for Assessment of Change table:

Analysis of the underlying trends is undertaken by the data providers.

Indicator description

Priority species are defined as those appearing on one or more of the biodiversity lists of each UK country (Natural Environmental and Rural Communities Act 2006 - Section 41 (England), Environment (Wales) Act 2016 section 7, Northern Ireland Priority Species List, Scottish Biodiversity List). The combined list contains 2,890 species in total. The priority species were highlighted as being of conservation concern for a variety of reasons, including rapid decline in some of their populations. Actions to conserve these priority species are included within the respective countries’ biodiversity or environment strategies.

Of the 2,890 species in the combined priority species list, the 228 for which robust quantitative time-series of relative species’ abundance are available are included in the indicator. These 228 species include birds (103), butterflies (24), mammals (13) and moths (88). This selection is taxonomically limited; it includes no vascular or non-vascular plants, fungi, amphibians, reptiles, or fish. The only invertebrates included are butterflies and moths. The species have not been selected as a representative sample of priority species and they cover only a limited range of taxonomic groups. The measure is therefore not fully representative of species in the wider countryside. The time series that have been combined cover different time periods, were collected using different methods and were analysed using different statistical techniques. In some cases, data have come from non-random survey samples. See the technical background document for more detail.

The relative abundance of a species will increase when the population of the species grows; it will decrease when the population of the species declines.

Between 1970 and 2021, the index of relative abundance of priority species in the UK fell from 100 to 37.

The long-term assessment was made by comparing the 95% credible interval (CI) of the final year with the starting value of the indicator. As the credible interval around the final indicator value 37 (95% CI: 34, 39) is entirely below the starting value (100) the time series was assessed as decreasing.

The same approach was applied to the most recent five-year (2016 to 2021) period to assess the short-term change. As the credible interval for the most recent year (2021, 95% CI: 34, 39) spanned the value for five years previous (2016, 35) the indicator is assessed as no significant change.

Relevance

Priorities for species and habitat conservation are set at a country level through country biodiversity or environment strategies. Each country has an identified list of priority species, which are of high conservation concern due, for example, to restricted range or population declines. The indicator therefore includes a substantial number of species that, by definition, are becoming less abundant.

Measures of abundance are more sensitive to change than measures of distribution (see indicator C4b). Nonetheless, if a threatened species that has been declining starts to recover, its distribution should stabilise, and may start to increase. If the proportion of species in the indicator that are stable or increasing grows, the indicator will start to decline less steeply. If the proportion declines, it will fall more steeply. Success can therefore be judged by reference to trends in both indicators C4a and C4b, as well as other information on other priority species for which there are insufficient data for inclusion in the indicator.

Background

The measure is a composite indicator of 228 species from four broad taxonomic groups, see the technical background document for a detailed breakdown of the species and groups included. The priority species identified in each of the four UK countries were highlighted as being of conservation concern for a variety of reasons, including their scarcity, their iconic nature or a rapid decline in their population. They are not representative of wider species in general. They do however include a range of taxonomic groups and will respond to the range of environmental pressures that biodiversity policy aims to address, including land use change, climate change, invasive species and pollution. The short-term assessment of change can be used to assess the impact of recent conservation efforts and policy aimed at halting and reversing species’ declines. However, natural fluctuations (particularly in invertebrate populations) and short-term response to weather may have a strong influence on the short-term assessment.

Regardless of advances in statistical techniques, there are likely to be species on the priority lists for which little monitoring or occurrence data are available. Reasons for this include rarity, difficulty of detection, or those for which monitoring methods are unreliable or unavailable. In order for the indicator to be more representative of priority species, a method of assessing the changing status of these remaining data-poor species would need to be considered.

The methodology for producing the indicator involves converting the time series for each species in the indicator into an index. Each time series is scaled as a percentage of its value in its first year (i.e. the first year has an index value of 100 regardless of when a species was first included in the indicator). This enables all species to be brought together on an equal basis – common species and rarer species are thereby given equal weighting. To create the composite index, a hierarchical modelling method for calculating multi-species indicators within a state-space formulation was used (Freeman et al. 2020). This method offers some advantages over the more traditional geometric mean method: it is robust, precise, adaptable to different data types and can cope with the issues often presented by biological monitoring data, such as varying start dates of datasets and missing values. The resulting index is an estimate of the geometric mean abundance, set to a value of 100 in the start year (the baseline). Changes subsequent to this reflect the average change in species’ abundance; if on average species’ trends doubled, the indicator would rise to 200, if they halved it would fall to a value of 50. A smoothing process is used to reduce the impact of between-year fluctuations – such as those caused by variation in weather – making underlying trends easier to detect. The smoothing parameter (number of knots) was set to the total number of years divided by three.

The Freeman method combines the individual species’ abundance trends, taking account of the confidence intervals around the individual trends. However, the method is Bayesian, and therefore produces credible intervals to show the variability around the combined index.

Each species in the indicator was weighted equally. When creating a species’ indicator, weighting may be used to try to address biases in a dataset, for example, if one taxonomic group is represented by far more species than another, the latter could be given a higher weight so that both taxonomic groups contribute equally to the overall indicator. Complicated weighting can, however, make the meaning and communication of the indicator less transparent. The main bias on the data is that some taxonomic groups are not represented at all, which cannot be addressed by weighting. For this reason, and to ensure clarity of communication, equal weighting was used.

The overall trend shows the balance across all the species included in the indicator. Individual species within each measure may be increasing or decreasing in abundance (Figure C4ai). Estimates will be revised when new data or improved methodologies are developed and will, if necessary, be applied retrospectively to earlier years. Further details about the species that are included in the indicator, and the methods used to create the priority species’ indicator can be found in the technical background document.

The headline indicator (Figure C4ai) masks variation between the taxonomic groups. Figure C4aii shows the index for each taxonomic group separately, generated using the same methods as the headline indicator. The taxonomic group indices show that moths have undergone the biggest decline, with an index value in 2021 that was only 16% of its value in 1970. Similar strong declines in moths were noted in C4b. Butterflies have also experienced a strong historical decline, with an index value in 2021 that was 32% of its value in 1976. These are counterbalanced by relative stability in the birds index (96% in 2021 relative to the base year of 1970) and the mammal index, which had a value of 81% in 2021 (relative to a base year of 1995).

Figure C4aii. Change in relative species’ abundance by taxonomic group, 1970 to 2021

Notes about Figure C4aii:

- The line graphs show the smoothed trend (solid line) with its 95% credible interval (shaded area). The width of the credible interval is in part determined by the proportion of species in the indicator for which data are available; the CI narrows as data become available for groups such as bats in the 1990s and widens as datasets such as the Rothamsted Insect Survey drop out before the final indicator year.

- The number of species included in each taxonomic group index are provided in brackets (mammals = 13 species; butterflies = 24 species; birds = 103 species; moths = 88 species).

- All species in the indicator are present on one or more of the country priority species lists (Natural Environmental and Rural Communities Act 2006 – Section 41 (England), Environment (Wales) Act 2016 section 7, Northern Ireland Priority Species List, Scottish Biodiversity List).

- This indicator is not directly comparable with the previous publication; the number of species included in the composite index has increased from 224 in 2021, to 228 here, with an additional 4 moth species added to the analysis.

Source: Bat Conservation Trust; British Trust for Ornithology; Butterfly Conservation; UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology; Defra; Joint Nature Conservation Committee; People’s Trust for Endangered Species; Rare Birds Breeding Panel; Rothamsted Research; Royal Society for the Protection of Birds; The State of Britain’s Larger Moths 2021.

Goals and Targets

The UK and England Biodiversity Indicators are currently being assessed alongside the Environment Improvement Plan Targets, and the new Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework Targets, when this work has been completed the references to Biodiversity 2020 and the Aichi Global Biodiversity Framework Targets will be updated.

Aichi Targets for which this is a primary indicator

Strategic Goal C. To improve the status of biodiversity by safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic diversity.

Target 12: By 2020, the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Aichi Targets for which this is a relevant indicator

Strategic Goal B. Reduce the direct pressures on biodiversity and promote sustainable use.

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Strategic Goal C. To improve the status of biodiversity by safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic diversity.

Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Web links for further information

- Bat Conservation Trust: The National Bat Monitoring Programme

- British Trust for Ornithology: Indicators of wild bird populations

- Butterfly Conservation: Butterflies and Moths

- UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme: Butterflies as indicators

- JNCC: Seabird Monitoring Programme

- People’s Trust for Endangered Species: National Dormouse Monitoring Programme

- UK Biodiversity Partnership: UK Biodiversity Action Plans

- Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust: National waterbird estimates

- NatureScot: Scottish Biodiversity List

- Wales Biodiversity Partnership: Section 7 priority species in Wales

- Natural England: S41 List of priority species in England

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency: Northern Ireland Priority Species List

References

Fox, R., Dennis, E.B., Harrower, C.A., et al. (2021) The State of Britain’s Larger Moths 2021. Butterfly Conservation, Rothamsted Research and UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Wareham, Dorset, UK.

Freeman, S., et al. (2020) A Generic Method for Estimating and Smoothing Multispecies Biodiversity Indicators Using Intermittent Data. Journal of Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Statistics, 26, 71 to 89. doi.org/10.1007/s13253-020-00410-6.

Downloads

Download the Datasheet and Technical background document from JNCC's Resource Hub.

Last updated: May 2023

Latest data:

Abundance data – 2021

This content is available on request as a pdf in non-accessible format. If you wish for a copy please go to the enquiries page.

Categories:

Published: .