ISSUE

Conservation • Exploration • Adventure

12

CORAL GARDENERS BUYING PRECIOUS TIME FOR THE C O R A L R E E F S O F TA H I T I

E X P E R I E N C E T H E E X C E P T I O N A L® P R I N C E S S YA C H T S . C O M

P r i n c e s s 7 5 M o to r Ya c h t

An experience without equal

“The diving at Wakatobi is out of this world. This is eco diving with as little impact as possible. Miles and miles of healthy corals with abundant and unique flora and fauna. And in our many years of diving, we met our best dive guide ever.� ~ Guido Bornemann

www.wakatobi.com

CREWCLOTHING.COM

WELCOME

Editor’s Letter Yo u a n sw e re d t h e c a l l i n w a ve s , s e n d i n g p a rc e l s o f j o y a c ro s s the oceans and a ro u n d t h e w o r l d - thoughtfulness and escapism at a time when it was needed most.

Oceanographic Magazine has always been about community. We wanted to create a publication that broke free from hobbyist allegiances and offered something for all ocean-goers regardless of how they interacted with our planet's blue spaces - something, ultimately, for the entire ocean community. In the two years since our first magazine went to print, our community has grown significantly - readership, social following and the variety of partner organisations with which we collaborate. From shark scientists to big barrel surfers, via technical divers and weekend sailors, Oceanographic is read, shared and enjoyed by a diverse community. When you add in the geographical spread of those readers - from Chile to Norway, Azerbaijan to Mexico and everywhere in between and the age range - entire classes of school children to retirees - that sense of connectedness and commonality truly is a beautiful thing. In these strange and challenging times of isolation it is these shared passions, values and loves that we should all focus on, that we can all derive strength from. Oceanographic is just a magazine, sure, but the community of people and shared values around it - all of you - is so much bigger than that.

Will Harrison Editor @waj.harrison @og_editor

That sense of togetherness was displayed most powerfully during our 'share a little joy' campaign in the early days of disruption when readers were invited to send a free copy of the magazine to a loved one in isolation. You answered the call in waves, sending parcels of joy across the oceans and around the world, offering your fellow ocean lovers a slice of the big blue at a time when they could not access it - thoughtfulness and escapism at a time when it was needed most. Thank you all for that - that is what community is all about. To all of you out there, wherever it is you call home: Stay safe, stay well, and stay connected.

Oceanographicmag

Oceanographic Issue 12

9

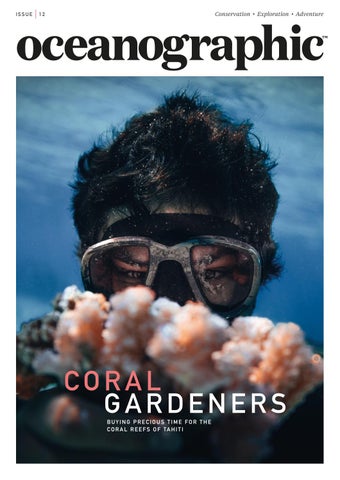

Contents O N T H E C OV E R

FEATURE S

C O R A L G A RD E N E RS

Tehapai, a Coral Gardeners volunteer, holds out a coral of the species 'Pocillopora verrucosa'. Photograph by Ryan Borne.

What does it take to protect a coral reef? Patience, dedication, determination and knowhow. These are the tools that an NGO in Mo'orea uses to defend its reefs and capture the attention of the global ocean community.

Get in touch PAG E 2 0 ED I TO R Will Harrison A S S I S TA N T E D I TO R

Beth Finney

CR EATI V E D I R E C TO R

Amelia Costley

D ES I G N A S S I S TA N T

Joanna Kilgour

PA RT N E R S H I P S D I R E C TOR

Chris Anson

YOUR OCEAN IMAGES

@oceanographic_mag @oceano_mag Oceanographicmag

I N S U P P O RT O F

A S S TO C K E D I N

For all enquiries regarding stockists, submissions, or just to say hello, please email [email protected] or call (+44) 20 3637 8680. Published in the UK by CXD MEDIA. Š 2020 CXD MEDIA. All rights reserved. Nothing in whole or in part may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

ISSN: 2516-5941

10

A collection of some of the most captivating ocean images shared on social media, both beautiful and arresting. Tag us or use #MYOCEAN for the opportunity to be featured. PAG E 1 2

CONTENTS

20%

PR O FIT-S HA R ING CO MMITM ENT TO O CEA N CO N SERVAT IO N . A PR O M IS E WE'R E PR O UD O F.

ANSWERS IN SNOW

CH A SI NG D R AG O NS

S AV IN G S AW F IS H

To what extent can citizen science contribute to remote microplastics research? To find out, Airbnb Sabbatical sent five volunteers to collect and analyse snow samples on Earth’s most unforgiving continent.

Of all the extraordinary creatures that reside in the ocean, seadragons are some of the most mythical. But, like so many marine animals, they're at risk from heating waters and habitat loss. What can be done to protect them?

Only five living species of sawfishes remain, and all five are threatened with extinction. Researchers at the NOAA Southeast Fisheries Science Center are working tirelessly to figure out how to save them from that fate.

Millions of sharks are hauled out of the ocean each year for their fins and their absence from the global seas is having a huge impact. Project Hiu seeks to convert those same shark fishermen into shark conservationists.

Some of the most fulfilling adventures require us to slow down. This is certainly true of Anclote Keys Island of Pasco County, where nature abounds both on land and in the water, people are few, and time is immaterial.

PAGE 30

PAG E 40

PAG E 8 4

PAG E 9 4

PAG E 1 0 2

BEHIND TH E L E N S

C O LUMN S

ANDY MANN

THE SOCIAL ECOLOGIST

PR O J E C T HIU

T HE MA R IN E B IO L O G IS T

T HE O C E A N AC T IV IS T

S L OW A DV E N TU RE

P R O J E C T AWARE

Each issue, we chat with one of the world’s leading ocean photographers and showcase a selection of their work. In this edition, we meet awardwinning photographer and SeaLegacy creative director, Andy Mann.

Big wave surf champion, environmentalist and social change advocate Dr Easkey Britton discusses the impact creating inclusive surfwear can have on women around the world.

Freediver and founder of I AM WATER, Hanli Prinsloo, shares her thoughts on how years of freediving have prepared her for the experience of discomfort when life is turned upside down.

Dr Simon Pierce, Principal Scientist at the Marine Megafauna Foundation, discusses the devastating impact ocean plastics are having on the global seabird population.

The team at Project AWARE, Oceanographic’s primary charity partner, discuss how vital sharks are as apex predators and what we need to do to help protect them.

PAGE 51

PAG E 38

PAG E 4 8

PAG E 9 2

PAG E 1 0 8

Oceanographic Issue 12

Pascal Van de Vendel Bali, Indonesia A nudibranch moves across the black sand ocean floor off the coast of Bali. Measuring less than 1cm, the Costasiella kuroshimae nudibranch is often referred to as Shaun the Sheep. SPONSORED BY

#MYOCEAN

#MYOCEAN

Evans Baudin Mexico Thousands of mobula rays gather in a large school off the coast of Cabo San Lucas, at the southern tip of Baja California. The rays are a commonly sighted from December to mid-January and then from May to July. SPONSORED BY

#MYOCEAN

Joe Leahy Hawaii

A turtle comes up for air off the coast of Oahu. Of the peaceful encounter, photographer Leahy says: “It seems like no matter what’s going on around them, sea turtles maintain the most care-free demeanour.” SPONSORED BY

#MYOCEAN

Martin Strmiska Raja Ampat A parrot fish patrols a reef in Misool, Raja Ampat. "Parrot fish are some of the most important fish species on the reef," says Strmiska. "They are the doctors, eating algae and dead coral, which keeps the reef healthy." SPONSORED BY

#MYOCEAN

Coral gardeners What does it take to protect a coral reef? Patience, dedication, determination and know-how. These are the tools that an NGO in Mo'orea uses to defend its reefs and capture the attention of the global ocean community. Wo rd s b y N a t a l i e H u n t e r- S m i t h P h o t o g ra p h s b y K e l s e y W i l l i a m s o n , R y a n B o rn e a n d B e n Th o u a rd

Oceanographic Issue 12

F E AT U R E

T

here are those who say that you can tell where in the world a photograph was taken based on the colour of the water. Truly, there is nowhere quite like French Polynesia to demonstrate this theory. The ocean there seems to have a unique blend – the deepest cerulean that melts into a dark powder blue, dappled with icy streaks from the sun. Almost all of the 118 islands have coral coastal marine ecosystems, with the exception of the Marquesas Islands. They boast nearly 200 species of corals, 1,200 species of fish and 1,000 species of crustaceans. However, after consecutive years of coastal development, the ongoing pressure of tourism, bleaching events and escalating climate change, the reef communities are declining. The coral rubble sweeps into the waves, distorting that instantly recognisable blue. However, on the small volcanic island of Tahiti, in the Mo’orea Island lagoon, a group of young ocean lovers has decided to do something to try and protect their paradise. The movement was founded nearly three years ago by Titouan Bernicot, who grew up on a pearl farm in Ahe, a small atoll at the North of the Tuamotu. “When I close my eyes at night, all I see is the ocean. It’s my everything,” he said. “From the mountains to the sea, everything here is connected. We are surfers, fishermen and freedivers. The coral reef gives us everything in our life. Endless joy and adventures, the food that we eat and the oxygen we breathe.” Since its launch, it has acquired ambassadors such as Diplo, Alexis Ren, Cristina Mittermeier, Jack Johnson, Paul Nicklen and (Shark Girl) Madison Stewart. Just like any other reef in the world, Mo’orea has been hit by rising ocean temperatures, escalating weather events and ocean acidification on the outer slope. Areas of the reef that are becoming wastelands of seaweed and dead coral rubble are on the rise. The lagoon itself faces the same threats with the added element of human impact. Pollution, divers treading on the reef, boats damaging it, chemical runoff from industry as well as huge freshwater inputs during the rainy season. It is estimated that around 75% of the world’s coral reefs are facing threats from pollution, overfishing and human activities or global heating, while coral reefs coverage has already declined by 30%-50% since the 1980s. Coral reefs cover less than 1% of the earth's surface and less than 2% of the ocean bottom but up to 25% of all marine life relies on them. We rely on them too, for the air we breathe, the food it provides and the livelihood it gives to millions of people. They are vital for protecting numerous island coastlines around the world from forceful ocean waves and some potentially devastating weather events. The larger and more intricate the reef is in terms of its structure, the more it can reduce wave energy. With so many different threats weakening these natural barriers, an increasing number of coastal residents are set to be at PREVIOUS PAGE: A restoration team member cementing coral fragments back onto the reef. THIS PAGE: Cleaning the ropes from algae to ensure the fragments' growth.

22

“When I close my eyes at night, all I see is the ocean. It's my everything. From the mountains to the sea, everything here is connected."

“The idea of restoration is not to regrow corals, but to revive an entire ecosystem, bringing benthos and fish back all along the food chain.�

F E AT U R E

PREVIOUS PAGE: Mo’orea, circled by coral reefs, enclosed by bright lagoons, covered by lush forests and soaring volcanic peaks. THIS PAGE: Corals are animals living in symbiosis with an algae called zooxanthellae.

F E AT U R E

risk. Without immediate and intelligent action, all coral reefs are at risk of disappearing by 2050, with disastrous consequences for marine life. Thankfully, Mo’orea is one of the more resilient reefs and has, so far, managed to mostly recover from major bleaching events. But with rising ocean temperatures, the Coral Gardeners are trying to act quickly and think ahead by looking out for ‘super corals’. These are individuals of any coral species that, for one reason or another, won't bleach when others do. The reason for that is often a stronger genetic background, that allows them to endure warm temperatures or longer periods of stress. “The issue behind climate change and coral bleachings is not simply the death of the corals,” explained Mathilde Loubeyres, the Coral Gardeners’ in-house scientist. “The issue is that the reef never comes back the way it was before in terms of coral assemblages. We are witnessing a change in morphology that translates into a loss of functionality. Over the years we are losing branching, foliose, digitate corals to encrusting, submassive or massive species. We are losing the three-dimensional structure that provides shelter for fish, habitat for all benthic species, and a barrier against waves and erosion. Without this three-dimensional structure, the reef flattens and it's the whole assemblage that shifts. This is what we're trying to restore. We try to select super corals of three-dimensional species to encourage the recovery of the reef as an ecosystem, not just as a coral reef.” The restoration process could be likened to gardening on land. Currently, the Coral Gardeners have four sites and five nurseries. They are working with a cementing technique while implementing the new super corals project. For the cementing technique, broken fragments are collected in the ocean and placed on underwater nursery tables. After a few weeks, these fragments are secured using marine cement on damaged areas of reef across five key zones in Marine Protected Areas of the Northern lagoon of Mo’orea. Outplant substrates consist of dead reef structures known as ‘coral potatoes’. The chosen outplanting surface needs to be scrubbed of all algae or sediment prior to cementing in order to maximise the coral piece’s chance of self-attachment. This technique provides a hard surface for the corals to

“From the mountains to the sea, everything here is connected. We are surfers, fishermen and freedivers. The coral reef gives us everything in life."

colonise immediately, before merging with the substrate, which then facilitates their growth. Over the following months, these newly planted marine habitats are closely monitored. Currently, the species of focus include Acropora (A.) hyacinthus, A. pulchra, A. cytherea, Pocillopora (P.) eydouxi, P. meandrina, P. verrucosa, Pavona cactus and Napopora irregularis. Of course, the mitigation of anthropic stressors with the help of the local community also has to play a role if their success record is set to continue long-term. Tahiti benefits from both Marine Protected Areas and the Rahui – a traditional Polynesian method of managing natural resources or seasonally restricting usage – with fishing exclusions and quotas. The Rahuis are an ancestral practice and as such are very much respected. “I am part of the restoration team so everyday we go out in the water for a different mission,” said team member Maoritai Teiho. “At the moment, we collect opportunity fragments on the ground of the lagoon. These are live pieces of corals broken by the current or marine life or human activities. Then we cement those fragments to dead bommies so they have a new place to attach themselves to grow on. When I was a child, I thought corals were rocks! We need every kid to know what a coral is, to not be like me and think that they are just rocks. People need to realise how important reefs are for life on this Earth.” Mathilde designed the new nurseries, set up collaborations with national research entities and manages them while training the team, monitoring the programmes and analysing all the data collected. “We regularly collect data on coral cover, coral growth, coral fitness, fish count of our donor and outplant sites, benthos survey; basically the usual reef-check basics with a few extra parameters,” said Mathilde. “The data allows us to assess not only coral growth and cover but the impact on the whole ecosystem. The idea of restoration is not to regrow corals, but to revive an entire ecosystem, bringing benthos and fish back all along the food chain.” They also use transect lines as a monitoring tool, to track the reefs’ health and evolution. A measuring tape is laid out over a section of reef and data is recorded in relation to that line, such as fish abundance, size and species. By repeating these surveys through time, the team can monitor the reefs’ richness and diversity. Each restoration site has its own needs. Restoration might not even be what the reef needs in certain places. They conduct a baseline study prior to any work, to assess the needs of the reef. If restoration is required and possible, then the team adapts the methods based on the environmental conditions of each site. Essentially, the goal is to restore the ecological function of lagoon coral reefs wherever possible. In the early days of the NGO, much of the focus started out on restoration, but the Coral Gardeners are taking things a step further. They are working on creating three permanent coral ‘gene banks’ from the careful sampling of large heat-resilient colonies located in the lagoon. By

Oceanographic Issue 12

27

setting up coral tables in scrupulously selected areas, complete with strings of coral micro-fragments, they can focus on climate change adaptation and the discovery of new super corals. Once they’ve grown on the ropes into ‘mother corals’, they will be trimmed every 6-12 months and those offcuts will be planted elsewhere in the lagoon of Mo’orea North. The hope is that by selecting super corals and outplanting them in damaged areas, they can hopefully improve the general resistance of the reef. It’s a simple yet effective process. Thus far, the Coral Gardeners have seen a 90% success rate from their hard work. “At Coral Gardeners, we have two main pillars: reef restoration and awareness,” Maoritai explained. “Regarding reef restoration, yes we plant corals but we also constantly work on new techniques that will help us in the future, even if temperatures rise. Regarding awareness, we go to schools, to conferences, we have ecotours for tourists and we are present on social media. Indeed, we want to spread the word so people realise the impact of climate change and adapt their habits so we all try to slow down this temperature rise.” People anywhere in the world can support the project and adopt a coral that the Coral Gardeners will care for. Alternatively, if you are in Mo'orea, you can go out to the sites yourself on a guided snorkel ecotour. It’s this sort of carefully curated experience that heartily welcomes people to the world of coral gardening, inspiring numerous individuals to care about the reef rather than brandishing the somewhat overused ‘it’s too late’ storyline. “Community is key,” added Maoritai. “We cannot save the reef alone. Climate change is impacting our oceans and we need everyone to adapt their habits so we can reverse the current trend and save the oceans. Everyone has a role to play, by adopting a coral, talking about corals and climate change around them and sharing meaningful content on social media for example.” Their work relies on millions of people worldwide feeling connected to the ocean, feeling like they can play a role in protecting it. They share educational content with more than 500,000 followers on Instagram. By August 2019, they had organised four conferences, 18 events, told the story of the reef in 22 classes and guided more than 500 tourists on their ecotour. “Just like other conservationists, we fight against people’s lifestyle and unwillingness to grasp the urgency of climate change,” adds Mathilde. “Restoration is nothing but a bandage on a wound, it is by no means a solution. We can restore all we want, but as long as we do not all tackle climate change together, our efforts are doomed in the long run. Conservation is a depressing and frustrating field overall, so being able to distance yourself from your work/passion is, to me, a vital skill in order to not to become overwhelmed.” In 2019, the Coral Gardeners replanted more than 11,000 coral fragments, directly educated 2,519 individuals and expanded their team to include 20 passionate ocean defenders. Workshops with young people on the island play a huge part in their community-based efforts. The children they work with already know that there is a problem, and that that problem will become their responsibility in the future, so the Coral Gardeners team show them what role they can play directly in protecting the reef. “We need to tackle climate change and alter our lifestyles now. We’re running out of time,” said Mathilde. "The ocean has always been my confident, the silent companion sharing happy moments, listening to all the struggles and shaking me up when I needed it. Being in or on the water has a way of calming my mind, reminding me of my priorities, of who I am and why I’m doing this. The underwater world is my safe place, where no one can talk to you, you just have to feel, to rely on your instincts. Feel the pressure on your body, heartbeat slowing down, movements becoming more fluid as the time seems to stop. It’s not silent by any means but it’s quiet in its own way, it’s peaceful.” This is by no means a quick fix. But through determination and dedication, the Coral Gardeners are making a difference, both in French Polynesia and around the world. Their methods and hard graft are buying some time for this small part of the Pacific, but they need the rest of the world to work alongside them to try to turn back the clocks on climate change before it’s too late.

A thriving coral reef off Mo'orea.

“We cannot save the reef alone. Climate change is impacting our oceans and we need everyone to adapt their habits so we can reverse the current trend and save the oceans."

BEHIND THE LENS

30

Oceanographic Issue 12

BEHIND THE LENS

FINDING ANSWERS

in the snow To what extent can citizen science contribute to remote microplastics research? To find out, Airbnb Sabbatical sent five volunteers to collect and analyse snow samples on Earth’s most unforgiving continent. Wo rd s b y K i r s t i e J o n e s - W i l l i a m s P h o t o g ra p h s b y Yu r i Ko z y rev

Oceanographic Issue 12

31

F E AT U R E

“When we look at microplastics in this environment,we must first recognise that plastic must interact within a realm of multiple stressors.�

32

Oceanographic Issue 12

F E AT U R E

W

hite, as far as the eye could see, dry, cold and an unrelenting wind bringing air straight from the Pole. The icy Antarctic Plateau’s immensity is disorienting and I look back to see my single track of footprints behind me and nothing but a thousand kilometres of snow ahead. Whilst it looks and feels like an untouched part of our planet, foreign in its vistas and remoteness, like it's entirely unconnected to back home, the opposite is in fact true. The Antarctic is inextricably linked to global climate cycles, sharing the same atmosphere and, as recent studies have shown, is undeniably impacted by the activity of human beings. To what extent, if any, the purely human-made pollutant, plastic had contaminated this continent was my reason for being here. Since my first hikes in the welsh mountains back home and seeing the development of the offshore windfarm from my school classroom, I have always been interested in our relationship with the natural environment. From the physical impact, both positive and negative, that we can have on its environment and resources, and the ways in which we try to explore it, manage it, protect it, govern it and connect with it. I was reading a magazine, much like this one, over a decade ago when my curiosity and admiration for Antarctica and our relationship with it was piqued. I still have the magazine and the pieces I highlighted; a special issue on climate change. There was an exposé on Antarctica and a summary of key discoveries since the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, which devoted the continent to peaceful scientific collaborations. Amongst them, the uncovering of the instability of the ozone layer, the so-called ozone hole due the chemical CFCs found in refrigerants, some of the most significant warming seen on the Antarctic Peninsula, and the effects of runaway warming on glacier retreat. It fascinated me. Here was this remote continent, connected to human beings only by the oceans and air, protected, at least for now, under a treaty, which regardless of its motivations was enabling peaceful, scientific exploration and preservation of its resources. It is for all these reasons, that Antarctica perfectly epitomises our complex relationship with the planet. I actively sought a line of research that would enable me to connect people with our natural environment and see the impacts we can have on it. Plastic pollution is without doubt one of the most tangible forms of

environmental crisis our planet faces and with this fact, there is an immense amount of responsibility to shine a light on the other ways in which we may negatively or positively impact our planet. I often think of it as the “gateway topic” to environmentalism. If you can get people to engage with plastic pollution, you start to see small changes in their behaviour, which are rooted in a changing perception of our responsibility to, and our reliance on the health of our natural world. But a connection with our oceans instils a deeper sense of connectivity with planet Earth and the impact that we can have on far flung lands, even back at home. Researching plastics in both the Arctic and Antarctic is bitter-sweet. The fact this field of research exists at all, and the complexity and number of ways in which we must try to decipher its potential impact, is often daunting, but the fact that, to some degree, an individual can be empowered by changing their behaviours and motivated to demand more responsible choices from their governments and providers is incredibly encouraging. I started a PhD back in October 2017, investigating microplastics and how they may behave as a contaminant in and around Antarctica. Microplastics are plastic pieces which are approximately less than 5mm, and at this size, capable of being ingested by animals that support the food chain, and interact with the environment in a multitude of complex ways. The ability to understand the relative risk of this contaminant around Antarctica relies upon the development of two separate lines of research. The first is to understand the most prevalent types of plastics that now exist in our natural environment, as mismanaged waste and how they may be distributed in our oceans and on land. Secondly, it is to determine how these contaminants interact both at a physical level, and a chemical level with organisms. This is particularly pertinent in the polar regions, where zooplankton are often keystone species. That is, that the smallest, insect-like animals of the ocean, such as Antarctic krill, support the rest of the marine food web by being a source of food for fish, seals, penguins and whales alike. Living in the coldest, ice-influenced waters, they have a reduced tolerance to environmental changes such as global heating and ocean acidification. When we look at microplastics in this environment, we must first recognise that plastic must interact within a realm of multiple stressors and so even small amounts of this pollutant may have a significant role to play. Over the last couple of years I have been able to carry out fieldwork in the waters around the Sub-Antarctic and along the Antarctic Peninsula, which may help me answer some of these questions. Studies show that thousands of microplastics are found per square kilometre in Antarctic waters, but this rarely includes synthetic fibres. This compared to a global average of 63,320 particles

LEFT: Collecting snow samples in stainless steel containers to minimise contamination. PREVIOUS PAGE: The Basler plane used to fly to the South Pole.

Oceanographic Issue 12

33

F E AT U R E

per square km (Eriksen et al/, 2014) is small, however by no means insignificant. With plastic release to the environment estimated at 4-12 metric tonnes in 2010 alone (Jambeck et al., 2015), and an estimated increase by three orders of magnitude by 2050 (Geyer et al., 2017), we expect to see this increase reflected in the polar regions as well. I strongly believe that a key to understanding and monitoring plastic pollution and its possible threat, is to have key areas for monitoring. One of the data gaps we currently have is the concentration of plastic in the Antarctic interior. Whilst areas adjacent to local human footprint – such as logistic basecamps where we were on my recent expedition – allow us to investigate the spread of plastic pollution from these localised source points, even more interesting is getting data in the remotest regions, such as on the Antarctic Plateau and remote glaciers at altitude. Here we can test to what extent larger atmospheric circulation can carry microplastics. When Airbnb first approached me with the idea of the Antarctic Sabbatical – a way to promote purpose driven travel through an experience where travellers give back to the community they visit – I felt a mixture of confusion and excitement. What could “citizen science” mean on a continent that technically had no citizens? Would it be possible to fill in this knowledge gap of microplastics in Antarctica and what was the best way to utilise the incredible global platform that Airbnb has? When we sat down to meet, it appeared as though we were aligned in our philosophies and had the same questions. Citizen science in this sense, was to evoke an idea of global citizenship through experiential learning and through this, hopefully inspire and help five environmental ambassadors. We wanted to bring an NGO on board that focussed on promoting and educating on sustainable living alongside interaction with our oceans. The Ocean Conservancy was the obvious choice, and having them partner allowed us to really solidify this idea of connectivity with Antarctica through our oceans. With more than 140,000 applicants, my inbox was inundated with questions and advice on what the perfect candidate looked like. For me at least, there wasn’t a perfect candidate. There was a perfect team, as is always the case in polar research – it is the team which matters, not the individual, and so it could look any number of ways. At the core of it, I think we all hoped there would just be a self-sustaining positive energy that would carry us through long days in the field, and ensure the longevity of the project after the fieldwork. I think we were all conscious of wanting to make sure that our team consisted of people with different backgrounds and therefore connecting with different audiences and opportunities to engage. Without mentioning the long list of truly incredible people that are needed for the organisation of a project like this, our core team in the field were the five Long lab days spent melting and filtering snow samples.

34

BEHIND THE LENS

“Being a visitor to somewhere like Antarctica, but feeling like you belong there and are truly at the mercy of Mother Nature, is one of the most grounding experiences you can have.� 35

TOP: For safety reasons, the team had to be roped together when out in the field. MIDDLE: The newly assembled team depart from Punta Arenas, Chile, to Union Glacier, Antarctica, on the Ilyushin. BOTTOM: Expedition basecamp.

F E AT U R E

volunteers who were from Norway, India, Hawaii, Arizona and Dubai, myself and our field guides from Antarctic Logistics and Expeditions (ALE), a logistics and tour operator company. Truly, the success of any fieldwork relies on the people. You need people with confidence, but a sense of humility. People with ideas and a curiosity, but who are also willing to accept a role and be relied upon to do it well, repeatedly, to be honest and communicate any problems. It’s a lot to ask from a person, but you’re not looking for a perfect embodiment of all of these things, you need a group of people who can bring out those qualities in one another. It was a big risk and so we were committed to making sure the team was built before we headed onto the ice. Just over two weeks was spent in Chile for this team building. This was strategic for two reasons. Firstly, it would allow us the time and facility for some lectures from myself, the Ocean Conservancy and partners in Chile from the University of GAIA, and INACH on plastic pollution and science in Antarctica. Secondly, it was to showcase one of the major countries that allows much of Antarctic research to be carried out. Punta Arenas in Chile is a hive of activity with expeditioners and scientists preparing for and returning from Antarctica. The volunteers had enough time to form bonds with the locals and work on a number of local citizen science projects. Airbnb had connected with Airbnb hosts across Punta Arenas to provide a platform for the most eco-conscious hosts and ensure our travels were single use plastic-free to the best of our abilities, and carbon offset. Our exact location in Antarctica was a place called Union Glacier, which is where ALE are based. Working with them not only put us in an ideal location to access remote areas inland, such as up on the Schanz glacier and the Antarctic Plateau, but it gave us access to an Antarctic family – evoking a sense of citizenship for those who lived there, albeit only temporarily. Being a visitor somewhere like Antarctica, but feeling like you belong there and are truly at the mercy of Mother Nature, is one of the most grounding experiences you can have to reconnect you with the natural world. It was an immense privilege to work there, with a team including other biologists, geologists, glaciologists, meteorologists and world class mountain guides and adventurers who wanted to learn more about the Sabbatical from the volunteers. We set up a laboratory on site and stayed for the next week or so, sometimes spending up to eight hours in the field. I wanted us to work as far away as we were logistically and safely able to do so, which meant heading out on ropes due to the risk of crevasses. Roles were assigned with the expectation of some nasty weather, with a sampler, scribe, and two meteorological observers, one who recorded wind speed and direction and another who photographed the sampled area – the patterns in the snow giving indication of the direction of recently drifted snow. Recording the surrounding environmental conditions are imperative when investigating for microplastics, and minimising our contamination in the field and the lab was also at the forefront of our minds. It is for this reason that we designed our sampling protocol in order to collect samples along the direction of prevailing wind, moving gradually upwind so as not to contaminate our sites. We had two teams carrying out the same task to have replicates, and investigate for bias that we might have between our sampling groups. The kit is all fairly basic and I was really keen to make sure we did one simple thing, so we dug small subsurface pits and collected snow in steel canisters, ecotankas, before taking them back to basecamp lab for filtering. These dry samples could then be observed under the microscope by the volunteers and now sit in my lab at Cambridge where I am analysing them using infrared analysis. Using the eye alone, you cannot determine for certain whether a particle or fiber is plastic, nor can you determine whether it was deposited there before you sampled or whether it came from one of the samplers. There is a long list of anti-contamination procedures that I’d written up and the volunteers were vigilant in carrying them out. By having a team of citizen scientists, in just a short space of time, we were able to collect and filter five times more samples than I had hoped for, and to be honest, ten times more than I had expected. To work in the polar regions is an immense privilege. What Airbnb wanted, and what I wanted and why ALE exists, is to afford this opportunity to others and to stir a sense of responsibility to travel with purpose. The uniqueness of this opportunity is surreal when I look back on it, and working in the laboratory back in the United Kingdom, I will be reminded of the truly international team that made this all possible and the spheres of influence this project can touch, by providing learning through experience. When you hear the messages that the citizen scientists have taken from it, and through meetings with the Ocean Conservancy on how they can make tangible differences, it is acutely apparent that the project brought together an Antarctic family. The Antarctic family is one that recognises its impermanence, its responsibilities as a visitor and is reminded daily of the vastness of our natural world, and the absolute necessity there is to understand it and respect it. And on a human level, it’s a bizarre realisation that sometimes it takes going the remotest of locations, to remind you of how vital people are and how much we need one another to make a positive impact.

Oceanographic Issue 12

37

Column

By Dr Easkey Britton

The social ecologist INTO THE SEA

I

can feel the flux – the whole planet and all of humanity in a state of flux. I waver between emotions of overwhelm or numbness, presence and surrender, a deep letting go, a slowing down and listening, a sinking and a stillness. Sometimes during the day I am struck by the raw beauty of the simplest, fleeting moment of sunlight on water, or observing the gradual unfurling of the buds on the trees day by day from my place of ‘self-isolation’. Other moments I feel the distance between me and my family and the longing for that physical contact like an ache inside. And I also feel and experience again and again a powerful sense of community and collaboration, empathy and understanding, a connection that transcends distance and language, and using what resources we have in new and innovative ways to overcome barriers. This is what is at the heart of the Seasuit Project, a creative journey that’s all about collaboration, between women, makers, designers, athletes, to take what we love to do – surfing – and make it easier for more women to do. In Ireland and the UK surfers are used to being fully clad in neoprene, especially in winter. But a decade ago in 2010, on an off-the-beaten-path surf trip to Iran, I found myself clad head-to-toe for very different reasons, where I became the first woman to surf in Baluchestan, a remote region to the south of Iran. Due to the country’s strict dress code imposed after the country’s 1979 Islamic Revolution women must cover up and wear a head covering, or hijab. In the surf I wore leggings, baggy boardshorts, longsleeved rashvest, a t-shirt and a hijab to ensure my head was covered. It was not ideal surf-wear – it felt extremely restrictive, heavy when wet and incredibly hot, making it difficult to wear in the surf. On my second visit there in 2013, I was joined by Iranian sports women (the trip is chronicled in the film “Into The Sea” by Marion Poizeau). Since then, surfing has been embraced by the local ethnic Baluch community, with efforts to explore its potential for bringing economic opportunity to an isolated region of Iran. In subsequent years when I returned to continue to support the development of surfing, I was joined by Shirin Gerami, Iran’s first female triathlete, who opened my eyes to a whole new way of understanding the experience of

38

our female bodies in water, overcoming challenges in sport to do what we love, and the particular challenges of appropriate, functional sportswear. The participation of Iranian women and girls continues to grow, and remains instrumental for the development of surfing. However, the issue of functional clothing to wear in the surf remains a barrier and a potentially dangerous challenge for women and girls to participate. The loose clothing and hijab fabric gets heavy when wet, is impossible to keep fixed to one’s head and can become a tangled mess when wiping out. If surfing was going to be accessible to the women in Iran – and other Muslim communities around the world – the issue of creating functional yet culturally conforming surfwear would have to be addressed. Some other performance hijabs already existed, but when we tested them they didn’t fully solve the particular challenges that come with surfing in them. When I shared my experiences and the idea of creating functional full-body surf-wear for women with my sponsor Finisterre, they embraced it as the ultimate design challenge. “Easkey came home telling us what an amazing experience she had in Iran and that there was a growing interest to do this activity, but that there was a barrier,” explains Finisterre’s Product Director, Debbie Luffman. “It was the perfect design problem. Not only was it a functional problem, but the clothing was actually stopping you from doing or enjoying the activity you wanted to do.” Finisterre took the challenge to students at the nearby Falmouth University and Plymouth College of Art. Whilst the design needed to conform to rules surrounding body modesty, a key part of the brief was also that the suit looked good and celebrated individuality, Debbie explained, “We told the students this was a function problem, and a sustainability challenge, but that they also had to consider aesthetics. Because when you are wearing sportswear, you have to feel strong and confident.” Throughout the project it has been supported by female designers, including Rachel Preston who created the first prototype from Synne Knutson’s original design. The final printed pattern was designed by Ayesha King inspired by the movement of water, creating a visual illusion that masks the contours of the body. Makers HQ, a female-owned social enterprise garment factory in Plymouth, made the first tester suits.

Oceanographic Issue 12

@easkeysurf

@easkeysurf

www.easkeybritton.com

Photograph by Abbi Hughes

The result is the Finisterre Seasuit – with an innovative cross-back strap system, making it easy for the wearer to step into and pull on over a wetsuit or leggings. It also features an adjustable elasticated hood that would stay put when duck diving or during a wipe-out, and is made from quick drying UPF 50+ ECONYL® recycled fabric. After years of design work on this collaborative passion project myself and Shirin got to test the very first Seasuit in the controlled surfscape of The Wave, in Bristol, which proved to be the perfect test site with its lab-like settings. Although the project was originally inspired by and born from the needs of women surfing in Iran, and created to encourage participation and growth of female surfing from different cultures, especially where societal norms surrounding how women should look and act controls their ability to access the surf – we quickly realised that the Seasuit could also help women who might prefer more modest surfwear for other reasons; from sensitive skin that

doesn’t like the sun, to individual body confidence for those who don’t want to wear a skin-tight wetsuit or bikini. It happens across sports in general, girls in their teenage years fall by the wayside in terms of participation. There are a whole load of reasons for that, but one is body image. The portrayal of what a female surfer should look like is pretty limited in the media. There should be lots of options of how to look in the water, and the Seasuit can facilitate that. "I am a huge believer that there is absolutely no barrier to sports participation. I think it's medicine in so many ways,” Shirin says. “The suit to me represents inclusion. I think it can have an absolutely huge impact and be a door opener to women, especially girls, to be able to gain the approval, blessing and the personal confidence to be able to go into the ocean and surf, have fun and be a part of this movement.” Doing this kind of work is what fuels me up in these strange times. EB

About Easkey Dr Easkey Britton, surfer and founder of Like Water, is a marine social scientist at the National University of Ireland Galway. Her work explores the relationship between people and the sea, using her passion for the ocean to create social change and connection across cultures. She currently resides in Donegal, Ireland. For more information on the Seasuit visit: www.finisterre.com

BEHIND THE LENS

40

Oceanographic Issue 12

FIGHTING FOR

dragons Of all the extraordinary creatures that reside in the ocean, seadragons are some of the most mythical. But, like so many marine animals, they're at risk from heating waters and habitat loss. But what can be done to protect them?

Wo rd s a n d p h o t o g ra p h s b y S c o t t Po r t e l l i

Oceanographic Issue 12

F E AT U R E

42

Oceanographic Issue 12

F E AT U R E

ABOVE: Seadragons have a life span of approximately 6-7 years, longer than most seahorses. LEFT: The weedy seadragons of the east coast of Australia favour kelp and seaweed habitats over seagrass. PREVIOUS PAGE: Seadragon predators include moray eels and octopus.

T

here is an extraordinary creature that lives, camouflaged by nature, in the southern waters of Australia. It truly is an evolutionary chameleon of the ocean. I was exposed to the ocean at an early age and learnt to appreciate it as an intrinsic part of Australian life. But it wasn’t until I became a diver that I started to pay attention to the wonders that lie beneath the waves. While the sheer variety of creatures that reside in the marine environment is somewhat incomprehensible, there is one delicate and little known species that has become my obsession. Weedy seadragons (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) have fascinated me ever since I first heard of their existence – I couldn’t believe these intricate creatures existed in my own backyard. Part of the seahorse family, Syngnathidae, they are only found along the southern coast of Australia, generally in cooler temperate waters. The first time I finally saw one while out diving, I followed it for as long as possible, almost neglecting my air consumption. I hadn’t realised just how big it would be, how detailed its patterns. I held my breath to listen to the snap of its proboscis as it fed on tiny mysid shrimp. I have now seen weedy seadragons in all parts of the southernmost regions off Australia and even the smallest differences in each individual fascinate me. The variations in their colours, their habitat and terrain, their physical size, their courting rituals – the list goes on. However, we are still unsure if these are variations in subspecies or simply examples of the same species adapting to their environment. I am driven to find out as much as I can

about these bizarre creatures and how I can play a part in protecting them. As syngnathids they are protected by some measures, but this doesn’t necessarily translate into tangible results. Protection generally relates to fishing and removal from their environment, but these are not the only threats to Australia’s seadragons. Species-level protection does help certain animals, but with declining habitat and poor genetic diversity, weedy seadragons may suffer from bigger issues. Weedy seadragons play an important role in maintaining the biodiversity of temperate reefs, as they feed on mysid shrimp and provide food for other species. The seadragon’s habitat can vary from seagrass to kelp forests and, in the east coast of Australia, we see the weedy populations mostly favouring the kelp and seaweed habitat, while further south in Victoria they will swim predominantly around seagrass beds and jetties. One notable observation is that we are seeing incremental changes in the way these seadragons look in different locations, which raises the question – are they a subspecies? Could they have genetic differences based on their location? Further research is being done to determine if these differences are enough to classify them as a separate subspecies. As with a lot of marine life, seadragons are under threat from habitat loss, the impact of climate change heating our oceans and increased pollutants from human excess. We have observed thinning of kelp in Sydney, which is an important source of shelter for the species. This loss

Oceanographic Issue 12

43

F E AT U R E

“If it wasn't for scuba divers giving many hours to collecting thousands of photos of weedies, we wouldn't have enough data to establish trends and make informed conclusions regarding the health of weedy populations. We are helping to monitor seadragon populations and track individuals using matching software...” impacts seadragons heavily, as their environment acts as a means of survival through camouflage. Their ability to blend into seaweed, kelp forests and seagrass beds and move with the surging ocean is why they have been successful as a species. But in many parts of Australia, the kelp forests are dying, and the seagrass is diminishing, which will have an impact on how these creatures will survive, or if they can adapt in any way at all. “They are a truly magical animal to watch in the wild thanks to their almost invisible fluttering fins and genuinely dragon-like appearance,” said John Turnbull, a marine ecologist and President of the Underwater Research Group of NSW. Turnbull runs a communitybased organisation that is dedicated to sharing information about the underwater world and ultimately helping to contribute to conservation efforts through citizen science. One of the key areas of focus is the weedy seadragon monitoring project, which supports The University of Technology, Sydney, Underwater Research Group and Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS). “They need habitat, which is diminishing, and so may become increasingly open to predation. They are also found in temperate waters only so may be impacted by warming oceans. We are seeing declines in numbers in some populations, which will impair their resilience due to diminishing genetic diversity.” Their physiology is fascinating. They have a long snout that they use to catch their prey and have a close vision of focus that extends a little beyond this. It could be the reason they hunt their prey in such close proximity. They continually feed on mysids, small shrimp like crustaceans and from juvenile age to being fully-grown they increase by 10 times their weight. Researchers have tagged weedy seadragons and have determined that their life span is approximately six to seven years, which is longer than most seahorses of the Syngnathidae family. The males carry a brood of eggs along the underside of their tail until they are ready to hatch which can be between 8-12 weeks. The brood of eggs are brightly coloured, possibly to deter predators as often bright colouring can serve as a warning to other marine

RIGHT: Seadragons have a long snout, which they use to feed on mysids.

44

animals that they are in some way poisonous. However, generally their colours and features are designed to blend in with their environment and provide a natural camouflage. Once born, the hatchlings are on their own, blending in to survive from any predators until they are fully grown. Weedy seadragons tend to have fewer offspring than many other fish species, but this may be a strategy to produce strong and healthy babies that have better chances to survive. They do have some predators, including moray eels and octopus, however they seem to be a resilient creature despite their lack of defences. As a photographer I am always looking for a new way to present a species that is photographed regularly, so I set myself a goal. For one year, I would photograph a weedy seadragon every month, using a wide lens for six months of the year and a macro for the others to see if I could really discover more about these creatures and their lives. At one stage, I dived the same spot every week for eight weeks so I could follow a male carrying a brood of eggs. This allowed me to see the astonishing development of each individual egg from an iridescent pink pearl to a semi-developed set of limbs, with visible eyes and organs. Sometimes a tail or fin would be protruding from an almost hatched egg. I can’t explain how addictive watching this process was and how focused I was as a photographer to capture this. This was the turning point. I then wanted to see how I could use this type of photography to support the research and understanding of these creatures. Encouraging divers and underwater photographers who are diving the same places regularly and shooting the same subjects over several years, is how this type of program can be most effective. You expand the ability to collect multiple data samples and by educating the divers who are willing participants, how to shoot the photos in a way that is useful for comparing data, this information becomes invaluable and allows scientists to extend the reach of their research. There are a number of organisations collaborating on seadragon research, specifically along the New South Wales coastline, Victoria and parts of Tasmania where seadragons are more prominent. The weedy seadragon monitoring program is reliant on citizen scientists taking quality photographs during dives. Every new seadragon photograph is analysed through a software program and then compared in an image library database. This project builds upon ecological data collected since 2001 from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) research group. “The IUCN had earlier rated the species as “Near Threatened” but then downgraded to “Least Concern”, which flies in the face of what we have seen,” said David Booth, Professor of Marine Ecology at the UTS. “We have contacted them and they are happy to receive our data for their next assessment. The best option is to protect the habitats, especially the kelps at the northern range edges, which are threatened by higher ocean temperatures and climate related storms, as well as minimise the direct pollution in places like Botany Bay, Sydney.”

Oceanographic Issue 12

BEHIND THE LENS

“Their physiology is fascinating. They have a long snout that they use to catch their prey and have a close vision of focus that extents a little beyond this.”. Oceanographic Issue 09

45

F E AT U R E

“As with a lot of our marine life, they are under threat from habitat loss, the impact of climate change heating our oceans and increased pollutants from human excess.” These IUCN classifications can be problematic when organisations are trying to protect a species or reduce habitat loss. It makes this research and the distribution of accurate information important to convince governments and local councils to support efforts to ensure the survival of the species. Booth spoke with me about the importance of these programs and providing accurate information to understand the species, behaviour and habitat to ensure the conservation of these marine animals. Research is being done to look at genetics and other environmental effects around the coastlines of southern Australia, but the fragility of the species and their retreating habitat is what concerns many scientists. With a suspected decline in the populations, now is the time to gather as much information as possible. This is where experts like Booth and Turnbull lead the way in encouraging citizen science on a larger scale, as key to extending the reach of this research. “If it wasn’t for scuba divers giving many hours to collecting thousands of photos of weedies, we wouldn’t have enough data to establish trends and make informed conclusions regarding the health of weedy populations,” added Turnbull. “We are helping to monitor seadragon populations and track individuals using matching software, and analysing genetic diversity to understand how populations differ from one location to another. Without recent, reliable information we can’t make good decisions that will translate into effective conservation. In the end, we have to judge our actions by a turnaround in weedy populations, and without good science we can’t achieve that.” Photography gives people a window into a subject or environment they may not necessarily have the chance to see, it allows us to educate and inspire others to dig deeper or dive further into the plight of a species or the understanding of a creature they may not even be aware exists. For me, telling a story that can raise awareness, help support science and inspire others to explore the ocean for themselves, is achieving what most photographers strive to do. My hope is that we find ways to protect the weedy seadragon's habitat. I hope we can learn more about these creatures and I hope more people can contribute to citizen science to increase the reach of what we can learn and for those committed to studying them, give them the relevant information to support initiatives, breeding programs, create sanctuaries and simply make sure these creatures are around for generations to experience.

46

The males carry a brood of eggs along the underside of their tail until they are ready to hatch.

Column

By Hanli Prinsloo

The ocean activist

DISCOMFORT AND FINDING PEACE WITHIN

“ Adaptability, resilience, mental strength, mindfulness and of course empathy are the superpowers we now need and this crisis is the ultimate teacher. We have that strength of water – to be soft and strong at the same time.”

Photograph by Peter Marshall

48

Oceanographic Issue 12

@hanliprinsloo

@hanliprinsloo

@hanliprinsloofreediver

About Hanli Hanli Prinsloo is a South African freediver and ocean advocate. She is the founder of I AM WATER, a Durban-based charity that seeks to reconnect South Africa's underserved urban youth with the ocean. www.iamwaterfoundation.org

T

oday I tried to count how many minutes of the last two decades I have spent holding my breath. Decade one of freediving competitively, I would train several five minute breath-holds a week with a maximum of just over six minutes every other day. Hundreds of dives down to 20m then 30m then 50m, then 60m and more ranging from 3-4 minutes at a time. Recent years inspired by relationship not time, depth or records. How long do you need to be down for an oceanic manta ray in Ecuador to accept your presence? How many turns and twirls before a dolphin wants to play at depth? Floating at the surface just above a singing humpback whale not daring to breathe. For two decades I have danced the dance of the living non-breathing. Teaching myself to be comfortable with the discomfort of being encased in a human body in the throes of relearning the way of water. Every breath-hold reaches a point of discomfort. Often a discomfort so great that every cell in your body shouts for escape. With my lung volume any breath-hold beyond four minutes is extremely uncomfortable. My body screams for oxygen as my diaphragm starts to contract trying to force me to breathe. Through training stillness, relaxation and mindfulness this state is now familiar. Not pleasant, but not frightening. I have become comfortable with discomfort. I know that though this is not comfortable, it is not dangerous. The last hundred years humanity seems to have been waging a war against discomfort in all forms. With mobile phones we don’t even need to commit to a coffee date anymore, if on the day it challenges my comfort to make it, I can just text and reschedule. All the way from UberEats to online travel bookings we have eliminated discomfort and disruption. We arrogantly believed that we were as in control as our technology promised us that we were. I am writing this from my couch in Cape Town in our first week of nationwide lockdown. In China they are slowly coming out of widespread lockdown, in Italy and Spain lockdown has progressed into grieving and in the US certain leaders are reluctantly accepting the seriousness of the situation. The world is reeling. It is highly uncomfortable. I have not been outside my boundary wall for days. Beaches and the ocean have been closed for use for more than ten days already. I am worried for our I AM WATER team and the majority of my countrymen and women based in communities without the privilege of a boundary or a garden. I watch as the developed world with all its wealth and resources come apart at the seams while other at-risk regions hold their breath to see if this beast will wreak the havoc on vulnerable communities. My body and mind have endured decades of deep discomfort training. I have voluntarily put myself in situations of risk physically and mentally. I have a strong grasp on what is far enough but not too far, I have a small army of highly trained risk assessors who live in my brain and responds when needed. For many of us around the world right now, there is great anxiety and a stripping of the freedom we’ve come to take for granted. We are starting to see very clearly the lies in this promise we have bought into and we are woefully unprepared. But we are not without options. Think of the times you’ve willingly embraced discomfort, risk or the unknown. The help we need at this time for our mental health and those we love is not out there anymore, our safety nets and the systems are not what we believed them to be. It has to be on the inside. We have to find that piece within that is comfortable with being deeply uncomfortable and invite her to stay. You don’t have to be a record-breaking freediver or extreme alpinist to embrace discomfort and still find peace. Now is as a good a time as any to learn. Adaptability, resilience, mental strength, mindfulness and of course empathy are the superpowers we now need and this crisis is the ultimate teacher. We have that strength of water - to be soft and strong at the same time. It’s in our very cells. HP

Oceanographic Issue 12

49

TR AVEL TO SEE THE WORLD, BUT EXPLORE TO DISCOVER IT.

ENGINEER HYDROCARBON AEROGMT II COSC-certified caliber Curved rotating bezel Revolutionary micro gas lights Crown protection system

Worn by Erwan Le Lann on Maewan Visit shop.ballwatch.ch

Behind the lens I N A S S O C I AT I O N W I T H

ANDY MANN Behind the Lens places a spotlight on the world’s foremost ocean conservation photographers. Each edition focusses on the work of an individual who continues to shape global public opinion through powerful imagery and compelling storytelling.

BEHIND THE LENS

Q&A ANDY MANN Emmy nominated director, National Geographic photographer, marine conservationist, public speaker, lead storyteller and creative director at SeaLegacy, Andy Mann is an American photographer, expedition leader and storyteller who has helped protect a diverse range of ecosystems from the Arctic to the Caribbean. His work has been recognised on numerous occasions, including being honoured with the Crystal Compass Award from the Royal Geographical Society. He is one of seven world-renowned judges in 2020's inaugural Ocean Photography Awards.

OC EA NO G R A PH IC M AGAZ I N E (OM ): H OW D I D YOU FIRST CONNECT WITH TH E OCEAN?

ANDY MANN (AM): I grew up on the Chesapeake Bay, in Virginia. After he retired my grandfather became a fisherman, so I remember growing up fishing with him, and going with him to check crab pots. That led to a youth-long obsession with fishing. I was just a rural country boy from Virginia but I did love the water. I thought that was my path, marine science, so I went to college and I studied fisheries management and I ended up getting a job back in Virginia after college working for the Department of Game and Fisheries. It was conservation-based, but it was more like fisheries management. By the age of 23, it just didn’t seem like the kind of work I wanted to be doing at that time, so I moved out to Colorado, fell in love with rock climbing and became a successful rock climbing photographer and filmmaker. For the next ten years, that was all I did – I worked for the climbing magazines and I travelled around the world. Being known for that kind of adventure was how I got picked up for National Geographic in 2013. The first assignment they put me on was a really remote marine science expedition to a place called Franz Josef Land, in Russia – it was sort of like coming full circle, this adventure, science-based expedition. For me it’s all so interesting – marine science is just so fascinating, and it means I will follow these people into any situation. I actually wasn’t dive-certified at the time but I was still shooting in the water, just staying at the surface. It just felt like I was able to find some purpose with my camera.

OM : WA S T H AT H OW YOU S H I F T E D F ROM ROC K CLIMBING TO CONSERVATION P H OTOGRAP H Y?

52

AM: I got back from that trip and a National Geographic explorer named Jess Cramp called me up and wanted me to go on an expedition to Fiji to shoot and create a film for the Waitt Foundation. She said: “I’m leading this shark expedition to Fiji for three weeks. I know you’re not dive-certified but I’m not going to tell the Navy Seal dive safety officer that you’re not, you’re a good storyteller, so you have two weeks to get dive certified.” I got certified in a heated pool in Boulder, Colorado, and so my first open water dive was to 120ft with 50 bull sharks in Fiji. I sucked through my tank in about 15 minutes. The dive officer, Joe Lepore, brought me up to the surface, and said “you’re not a diver, are you?” I came clean, but I think he figured he was stuck with me for the next three weeks anyway so he became more of a mentor.

Oceanographic Issue 12

BEHIND THE LENS

O M: H OW C AN M E D I A I M PAC T T H E M ARINE SCIENCE WORLD?

AM: I did another eight Waitt Foundation expeditions over the following few years, as well as a couple of expeditions for National Geographic’s Pristine Seas, and I worked in-house for a lot of ocean foundations, just because I had the right skill set. I can go on a ten-day expedition and get off the boat with all the necessary media assets for those scientists that were leaving the boat, and they loved having those assets. I heard so much about how that was a tool that they didn’t really have, that they could really use. Having engaging photographs and video meant they could go back to their universities, give presentations and show funders what they were working on in the hope that they could raise more to go back – media was important for that.

Science and media, when they mesh together like that, it can really work wonders. On that first Fiji expedition, it was my job to edit a film together in the time it took for our vessel to run back to port, which I would have to present to the Prime Minister with a short keynote. It had to inspire him enough to decide to protect this marine area. I took that so seriously at the time – I felt like if I didn’t make a sweet film the ocean would die! This was my shot. Of course, it wasn’t that serious, he came on board, I think he liked the film and it was fine, but I had that sense of purpose, I put that pressure on myself. I still do.

O M: H OW I M P ORTAN T WAS I T F OR YO U TO FIND P URP OSE IN YOUR WORK?

AM: It was everything. When we got back from Franz Josef Land on that first National Geographic assignment, our team won a Crystal Compass award from the Royal Geographical Society for the work we did, and a year later Russia created the largest Arctic National Park in the world, encompassing all of Franz Josef Land. At the time I was like ‘wow the work I’m doing is saving the world!’ Now I realise how much more there is behind big decisions like that. I was just a kid with a camera, but I was being trusted, I was finding purpose and returning to my roots in a way. So the purpose is what drove everything, for sure. And access, because that was only seven years ago. What really drove things for me really fast was the relationships that I had in the field. It was how I shot so many stories in climbing too – I was friends with all of the athletes, they were some of my best friends and whenever they were going somewhere they wanted me to come with them. You form those bonds in the field, those stories and misadventures that you’ll never forget. Then marine scientists became my red carpet to see the world. Literally that first trip, there were five different marine science groups and they all went off and did five more projects individually. I was raising my own money to go on some of these trips too, and just getting as much time on these boats as I could. It didn’t take long before I was getting more and more calls to go on marine science expeditions.

O M: WA S T H E RE A S P E C I F I C M OM E N T WH EN TH E P ENNY DROP P ED AND YOU KNEW YOU PER S O NAL LY WAN T E D TO P ROT E C T TH E OCEAN?

AM: Sharks did that for me, for sure. Being in the water with oceanic whitetip sharks, a species I’ve done a lot of work with for the past six years. I was spending all day in the water with one or two sharks, just so excited and fascinated, so blown away by their beauty, power and grace. On every dive I think about how amazing these animals are, and how lucky I am to be in the water with a live shark. Then to think about the hundreds of millions of sharks that are killed every year, it just makes you feel – it’s tough. Doing so much work with oceanic whitetips I definitely got a sense of their personalities. If you’re in tune to the natural world, it’s pretty clear that sharks have certain behaviours that are undeniably charismatic. It’s powerful when they look at you – I feel like there’s a rudimentary understanding. It’s amazing that you can get in the water with one of the most powerful apex predators on the planet, and it’s just swimming along and moving slowly, you can understand that you’re not on the menu. You don’t feel threatened, you feel excited. So there’s just something given off there that you’re relating to and connecting to. You’re reading something in that situation.

Continued on p.80... Oceanographic Issue 12

53

BEHIND THE LENS

Q&A Continued...

OM: YO U W ER E IN VOLV E D W I T H T H E BL U N T NOSE SIX-GILL SH ARK TAGGING P ROJECT – WAS TH AT YO UR F IR ST F ORAY I N TO D E E P S E A E X P EDITIONS?

AM: Yeah, it was my first time in a submersible. This was through OceanX and with one of the scientists I’d met on the Fiji expedition. He’d started trying to tag the bluntnose six-gill, which is an amazing shark, it’s the main apex predator from 500-3,000m, besides maybe the sperm whale and the giant squid. The bluntnose six-gill is the size of a great white and they’re top dog down there, but no one has really studied them because they live so deep. Around ten years ago they caught a couple to tag in the Bahamas using extremely long lines, but it didn’t seem like the sharks survived that experience. They’d never seen light, they’d never come up to the surface, they were brought up really quickly and they were handled and tagged. Even though they swam back down and visually, they looked ok, the satellite tag didn’t show any movement afterwards. The scientists realised that they couldn’t work on these sharks on the surface, they had to go down there. So that’s when they put a proposal into OceanX to use their submersibles. Some of it was so high-tech, but other bits were so rudimentary. For example, the subs had ultraviolet lasers and a sophisticated speargun system with a trigger on the inside, but at the same time, we just zip tied a load of tuna carcasses to the front of this thing. We went down 2,500 feet to the bottom and shut the lights off. We sat there, waiting. They’re tiny subs – so we just waited for the sub to start shaking. Then we put on red lights and the shark was right there, tearing up the tuna. We flipped on the lasers to help guide the little dart – the aim needed to be on the upper meat of their back. On the third dive of the third expedition (I wasn’t on the first two) they were able to put one in.

It was the most profound experience of my adult life. Going to the bottom of the ocean and spending that much time down there. The dives are around six hours each and most of the time you’re just sitting there, waiting. But it’s exactly what you’d think the deep sea was like. You’re in this big acrylic dome, so once you’re in the water it looks like there are no walls. It’s so quiet, and you realise you’re probably the only people at the bottom of the ocean at that time – it’s like being on Everest, so far away from all of the drama, and social media and everything else. It feels like it’s 200 million years ago, back to the beginning of life on Earth. And then, as you come up, the last 10 feet, there’s an element of sadness. As soon as we popped up I saw all these lights, giant cranes, lots of people diving to us and our phones were activated again. I remember thinking: “Oh my god this world is so crazy.” It’s like coming out of a long meditation.

OM: D O YO U F EEL L I K E YOU ’ RE S T I L L S E E K I NG TH AT ESCAP ISM ALONGSIDE YOUR CO NS ERVAT IO N E N D E AVOU RS ?

AM: Yes definitely. I guess I don’t give it the recognition, that that is partly why I love it so much. The further I am from the water the more I realise that I need to be in the water. It’s that shutting down of the nervous system that I crave.

OM: IN YO U R EX P E RI E N C E S W H AT ARE T H E MAIN CONCERNS TH AT BLOCK MPAS AND H OW DO YO U PER S O NA LLY GO ABOU T TAC K L I N G T H OSE?

80

AM: Right now, I feel like it’s politics, semantics and egos. I’m working a lot in Timor Leste, and so I now know the President and the Prime Minister very well. I visited them and convinced them to protect huge amounts of their waters, which hosts one of the most biodiverse coral reefs on the planet, and took them to Washington D.C. to get some help. We needed to come up with environmental law policies and learn what some of these parks should look like. I’m still from the school of 'We Are Running Out of Time' – I think we need to just protect it, draw a line around it and say, ‘no more’, now. And then come in with a strategy and a roadmap for protection. Then we can start to figure out how this can be turned into a blue economy, how this can benefit the people and how this can regenerate the fishery – all that stuff comes with it naturally. I know I’m not a policy guy, but I just see how these things can move so slowly. As soon as you involve everybody, the fisheries office, the environmental office, the tourism office and so on, suddenly there are too many considerations that have to be taken into account. They’re trying to make sure that the fishing industry is happy, that the hotel industry is happy and after all that, you don’t get anything particularly special besides a paper park and maybe a little designation. By the time it’s all said and done, I feel like we need to be a little more aggressive and more ambitious. But that’s a luxury too, to be able to have those conversations. The biggest thing that’s in the way of these parks is poverty. There are so many countries that don’t have a system set up that’s going

Oceanographic Issue 12

BEHIND THE LENS

to benefit their people. Island nations care, but they’re small and they rely on the ocean. They’ve been preached at by NGOs and foundations for the last decade – they get it. But you have to offset their fishing somehow, whether it’s somehow subsidising that livelihood for 10 years then allowing them to fish the spillover, or deciding on a rotating season throughout the park where they can just use artisanal methods. But it’s hard. No one is doing it perfectly. O M: W H AT D O YOU H OP E TO AC H I E V E IN TIMOR LESTE?

AM: The goal is to protect Atauro Island and that coral reef. We went on a SeaLegacy expedition there last year and shot for a few weeks. We went to the office of Xanana Gusmão – he’s the most powerful man in the country, he was their first President – and we asked him to protect it. We said: “If you do this, we will go with you to the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon to make the announcement – your country and your legacy depends on this. We can turn this into an economy.” And he agreed to do it. We walked out of his office pretty bewildered. It was at that point that so many people started getting involved, so it got a little overwhelming. But it’s getting there. They’re going to make the announcement in June. It was media for sure that helped that lightbulb go off in their heads.

O M: W H AT ARE T H E K E Y T H RE AT S TO TIMOR LESTE’S REEFS? AM: There’s some illegal fishing, longlining, shark finning – it happens, but it’s not a lot. Maybe a couple of times a year. But you can turn places into wastelands in one trip if it’s a big enough boat. The problem would be outside countries coming in and fishing, because they as a country don’t have what I would call a commercial or industrial fishing fleet. It’s all about cordoning this area off to stop outside fleets coming in. What’s interesting about Timor Leste is that it was a conflict country from 1975 until 2005, so there was no tourism and it was just left alone. No hotels went up. There’s some spearfishing and fishing using hand dug out canoes out on the reef, but it doesn’t seem like that’s having a huge impact. So it was preserved, by conflict and crocodiles. They actually worship the crocodile. According to legend, Timor Leste is the back of a crocodile that came out of the sea and fostered their existence, so it’s illegal to kill them. They live in the mangroves, which is the nursery for all the reef fish, so it keeps all those nutrients flowing in and out of the reef and that ecosystem remains intact. The crocodile story is fascinating, because a lot of people are killed by crocodiles but they don’t report it, because the lore says that the crocodiles kill the bad souls. If a family member is killed by a crocodile, they don’t want to dishonour their life by reporting it, in case the community thinks they had a bad soul. O M: S O T H I S I S A RARE OP P ORT U N I TY TO SAVE SOMETH ING BEFORE WE DESTROY IT.