Abstract

Incident velocity and incident angle are important parameters for Martian aeolian research. In this paper we have established a model for investigating the saltation of sand in steady state, mainly considering the hopping of sand in the air and sand–bed collision process. The model proves to be able to predict sand motion in steady-state saltation on Earth well both qualitatively and quantitatively. Thus, it was applied to the study of sand saltation on Mars. With the help of the model, we found incident velocities and incident angles of Martian grains in steady-state saltation in cases of various wind strengths. Then, these predicted velocities and angles were compared with previous studies. Besides, the model also can show information on lift-off parameters of saltating particles. Therefore, it allows us to study other features in aeolian processes such as the saltation length and sand transport rate.

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The successful landing of Curiosity Rover makes more people pay attention to the 'red planet' on which aeolian features are prevailing (Malin and Edgett 2001). Studying these features and their formation and development could be helpful in understanding the climate change on Mars (Gardin et al 2012). Also, these studies could be useful for the selection of mission landing sites (Golombek et al 2012) and survey routines (Grotzinger et al 2012) and avoiding the experience of Spirit Mission (Kerr 2009). It is well known that saltation plays a leading role in wind erosion events (Bagnold 1941, Shao 2008, Zheng 2009). Saltation is the main factor that shapes the Martian surface (Kok 2010a). The saltation of sand not only creates sand ripples and dunes (Zheng 2009), but also is important for the release of dust (Shao 2008), especially on Mars where dust storms and dust devils are frequent (Cantor et al 2001, Balme and Greeley 2006). Therefore, a clear and comprehensive study on the saltation of sand grains is a prerequisite before going further.

With the development of an exploring technique, scientists have recently made a breakthrough in the understanding of Martian aeolian features. In the first observations, they found no evidence of the motion of sand ripples and dunes on Mars (Geissler 2005). A popular explanation is that the aerodynamic entrainment threshold wind of Martian sand is much larger than that on Earth and the wind on the Martian surface is rarely over the threshold (Fenton et al 2005). However, recent reports showed that those features which were thought to be almost immobile (Almeida et al 2008) are indeed able to migrate under the current Martian climate (Bourke et al 2008, Hansen et al 2011). The migration speeds of sand ripples and dunes (Bridges et al 2012a), as well as the sand flux (Bridges et al 2012b), are probably equivalent to those on Earth. These new findings force us to rescan the aeolian process on Mars, particularly the saltation of sand particles.

The incident velocity and the incident angle as well as their distributions are important parameters for wind erosion simulation (Anderson and Haff 1988, Werner 1990, Zheng et al 2005, Ammi et al 2009, Zheng 2009). Since we cannot measure the motion of sand directly, simulation becomes the unique method for studying the aeolian process on the Martian surface. Besides, there have been very few studies on incident parameters of saltating grains on Mars.

Early simulations of saltating trajectories of Martian grains were conducted by White et al (1976) and White (1979). They found that the speed of sand particles on Mars was greater than that on Earth, and the ratio of final particle speed to threshold friction speed was several times that of saltation on Earth. The incident angle they got (generally less than 3°) is much lower than Earth's. Almeida et al (2008) employed Fluent to simulate the saltation of sand by solving the turbulent wind field inside a wind tunnel and the air feedback with the dragged particles. They found that the average incident speeds of saltating sand increase with wind strength on both Mars and Earth, and the average incident speed of Martian particles was generally 5–10 times higher than that of terrestrial particles. The average incident angles they possessed decreased with wind strength on both Mars and Earth. The average incident angle of Martian particles has the same order of magnitude as that of terrestrial particles. In addition, their simulations showed that the impact threshold of sand saltation was much lower than aerodynamic threshold. This finding is consistent with the result of Claudin and Andreotti (2006) that was obtained by considering the hysteresis between static and dynamic thresholds, viscous force and cohesive force. However, in their simulations, the splash process on the sand bed was ignored (Kok 2010a), and their results therefore need verification.

Kok (2010a) parameterized the hysteresis phenomenon into his numerical model. The modeling results showed that the hysteresis effect causes saltation to occur for a much lower wind speed than previously thought. The impact threshold required for sustaining saltation on Mars was an order of magnitude smaller than the aerodynamic threshold required to initiate it. He pointed out that since the impact threshold is very low, once particles were initiated, saltation could be maintained under the current Martian environment. His findings provide an explanation for the recently confirmed motion of sand ripples and dunes on Mars. Depending on the numerical model, he found that the incident and the lift-off speed of saltating particles on the Martian surface had a weak dependence on wind strength. Furthermore, he theoretically derived the averaged incident speed by assuming a plausible distribution of the incident speed (Kok 2010b). The derived mean incident speed of saltating particles on Mars does not change with wind strength and has the same order of magnitude as that on Earth. But do the incident and the lift-off speeds of saltating particles not vary with wind strength? Kok et al (2012) also stated that 'although the mean speed of particles at the surface thus remains approximately constant with u*, the probability distribution of particles' speed at the surface does not'. Indeed, the probability distribution of particle speed near the sand bed will broaden. The probability of high speed increases with u* and the probability of low speed therefore decreases with u*. Again, although some experimental evidence was cited to support his idea, analyses and discussion in the following (see section 4.2) show that the idea is still challengeable. Moreover, some other experiments (Cheng et al 2006, 2009, Kang et al 2008) showed that the speeds of saltating particles near the sand bed change with wind strength. Therefore, it is still an open question whether or not the incident velocity of saltating particles changes with wind strength. In addition, the incident angle has significant effects on lift-off velocity and lift-off angle of rebounded particles (Werner 1990, Ammi et al 2009) as well as the number of ejected particles. Like most earlier models, the influence of incident angle was neglected in Kok's model (Kok and Renno 2009) because the range of incident angles was thought to be narrow. However, some experiments (Dong et al 2002, Kang et al 2008, Rasmussen and Sorensen 2008) suggested that the incident angle ranges from 0 to 180° and therefore averaged incident angle is large. So, the influence of incident angle may not be ignored.

Generally speaking, our understanding of incident parameters (velocity and angle) of saltating sand grains on Mars is far from sufficient. The relationship between incident parameters of saltating particles under Martian conditions and that under terrestrial conditions is still unclear. Hence, we have focused on the incident parameters of Martian saltating sand in steady state here. In section 2, we establish a model to investigate the saltation of sand in the steady state, mainly considering hopping of sand in the air and sand–bed collision process. Depending on this model, we studied the incident velocity and the incident angle of saltating particles on both Mars and Earth. In section 3, the established model is verified by experimental results under terrestrial conditions. The distributions of incident velocity and the incident angle of saltating particles in the cases of different wind strengths are shown in section 4.1. Then, the averaged incident speeds and incident angles are shown and discussed in sections 4.2 and 4.3, respectively. Finally, a concise conclusion is presented at the end.

2. Methods

The distributions of lift-off and fall speed of sand particles are link-bridges between the motion of single sand particles and the performance of sand flux, and are usually obtained from experimental data. So far, most numerical studies on terrestrial aeolian erosion have been carried out by employing these distributions (Anderson and Haff 1988, Zheng et al 2005). However, it is impossible for us to conduct quantitative aeolian research on Mars as we did on Earth, because we cannot directly measure the motion of sand particles on Mars and therefore lack the distributions of particle velocities. Kok (2010b) attempted to investigate the wind erosion of the Martian surface by assuming a weak dependence of particle saltation speed on wind strength near the sand bed. Nevertheless, as we pointed out, the validity of the hypothesis is still in doubt and needs confirmation. Therefore, it is necessary to find a new way that includes the basic mechanisms of sand motion to look for incident velocities and incident angles of saltating grains on Mars.

In this section, such a model is established. However, we have little information about the distribution of saltating particle speed on Mars. Therefore, in our model, we assumed that sand particles have been initiated and therefore provided an initial distribution of speed for saltating particles. Then, these particles were driven to hop in the air and collide with the sand bed alternately by wind, with a systematic adjustment of particle velocity (angle) distribution. The continuous hops and collisions would not stop until both speed distributions and angle distributions of particles reach the steady state. This steady state means the increased momentum of particles transferred from the air is balanced with the dissipative momentum during the sand–bed collision process. These stable distributions are our targets.

The modeling of aeolian sand transport was generally subdivided into four processes: aerodynamic entrainment, grain hopping, grain–bed collision and wind field modification (Anderson and Haff 1988). Here, the aerodynamic entrainment was neglected, because our aim is to find the stable speed distribution in steady-state saltation where the mechanism of impact entrainment dominates (Kok 2010a, Pähtz et al 2012). Thus, we mainly describe the remaining three processes in the following.

2.1. Equations of saltation

In fact, sand particles are driven by multiple forces, such as gravity, aerodynamic drag, lift force, Magnus force and so on (Zheng 2009). However, gravity and aerodynamic drag were mainly considered for the calculation of sand trajectories (Feng et al 2009, Zheng 2009). The equations of sand movements (Zheng 2009) are shown as follows:

where Vx and Vy are the horizontal and the vertical speed of sand particles, respectively, and u is the horizontal speed of wind at vertical height. D is the particle diameter and m is the mass of a sand particle. ρa is the density of air. ν and η are the kinematic and the dynamic viscosity, respectively, and ν = η/ρa. Note that g is a gravity constant.

2.2. Wind profile

It is known that the movement of sand particles can alter the wind profile significantly (Shao 2008). For simplification, a wind profile measured in the steady-state saltation is employed here. Thus, the effect of sand particles on the wind is included in our model. The selected wind profile, which was analytically derived based on experimental data (Feng et al 2009), is expressed as follows:

where u* and u*it are the friction speed of wind and the impact threshold friction speed, respectively. κ is the von Karman constant and is taken as 0.41. y0 is the roughness length of the sand surface and is defined as D/30.

2.3. Stochastic particle–bed collision

Sand–bed collision determines the distributions of lift-off velocity and lift-off angle of sand particles, and therefore plays an important role in the transport of wind-blown sand (Zheng et al 2005, Kok 2010b). A stochastic particle–bed collision model was proposed by Zheng et al (2005). Here, the model is briefly introduced. Since the sand–bed collision process is very complex, a reasonable and effective simplification is needed. Thus, the particles in a collision event were divided into three parts by Zheng et al (2005), as shown in figure 1. The first one is the incident particle (A) in saltation; the second one is the impacted particle (B), which usually is resting or creeping on the sand bed; the last part includes the particles around particle B as well as other particles on the bed and this part is denoted as C. Consequently, based on the collision theory and momentum balance, Zheng et al (2005) derived the analytic solutions of speeds of lift-off particles after collision. The detailed expressions are listed in section A.1 of the appendix. These expressions show that the lift-off speeds (Vreb and Veje) of particles are functions of incident speed (Vimp), speed of particles on the bed (Vsur) and incident angle (θ0) as well as multiple random variables (α and β). The model of Zheng et al (2005) is therefore used here to solve the sand–bed collision. So, the influence of incident angle is included in this paper apart from consideration of incident velocity as usual.

Figure 1. Sketch of the stochastic particle–bed collision. A, B and C represent the incident particle, the impacted particle on the bed and other particles in the bed, respectively. Vimp and Vsur are the velocity of the incident sand in saltation and that of the impacted sand on the bed before collision, respectively. Vreb and Veje denote the velocity of the rebounded particle and that of the ejected particle after collision, respectively. α, β and θ0 are the contact angle, impact angle and incident angle, respectively. α and β are random variables.

Download figure:

Standard image2.4. Model procedures

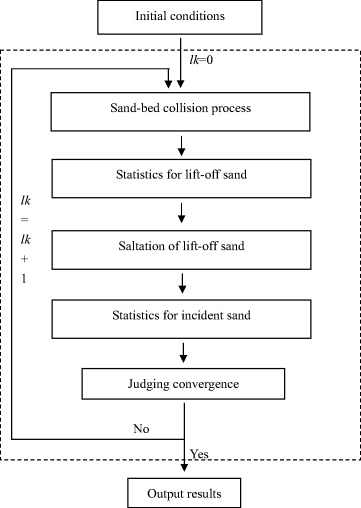

In this subsection, we describe the procedures of our model in detail. Also, we show a flowchart in figure 2 to help the reader.

- Determining the initial conditions. Three conditions are given, i.e. wind speed, the probability distribution of incident velocity and the probability distribution of incident angle. The wind speed is determined by a given friction speed u* by employing equation (2). Because it is assumed that sand particles have been initiated in our model, an initial probability density distribution of incident speed is given for these saltating particles. In other words, we first assumed that the particles were impacting into the bed at the beginning of modeling. The initial probability density distribution is denoted as flk=0(Vimp). The lk (>0) represents the loop in the model and lk = 0 means the initial condition before a run. In most previous models, all lifted particles, no matter what the speed of a particle is, were assumed to follow the same distribution of lift-off angle. This treatment may overestimate or underestimate the movements of lift-off particles, since the angle of a particle appears to be related to its corresponding speed (Rice et al 1996). In this paper, we performed statistics both for the population probability density distribution flk(θ) of all lift-off (incident) particles as usual and for the conditional probability density distribution flkv (θv) of lift-off (incident) particles that have the same speed. The conditional probability density distribution flkv (θv) shows us a clearer scenario of the particle movement. Hence, we chose flkv (θv) to describe the motion of particles instead of flk=0(θ). Here, for those particles which have been initiated, a conditional probability density function flk=0vimp (θvimp) of incident angle was selected as the initial condition. Due to the consideration above, our model seems to hardly change with the initial distributions (see section 3.1). Therefore, during our calculations, the initial incident speed Vimp was determined as a small constant value 0.5 m s−1, and the incident angle θvimp of incident particles ranges from 8 to 28° uniformly.

- The sand–bed collision process. Firstly, we divided the distribution ranges of incident speed (Vimp) and incident angle (θvimp), which were obtained in the lkth loop (lk = 0 for the initial condition), into uniform segments. That is, we have Vi+1imp = Viimp + dVimp/2.0, θj+1vimp = θjvimp + dθvimp/2.0, where i = 1, 2,..., nl, j = 1, 2,..., ml. nl and ml are the total numbers of segments for speed and angle, respectively. dVimp and dθvimp are the widths of each speed segment and angle segment, respectively. Thus, once the probability density distribution flk(Vimp) of the incident speed and the conditional probability density distribution fvimp(θvimp) of angles for each speed are determined, we can find the probability of the incident event with speed (Viimp) and angle (θjvimp). The probability could be expressed as Sij = flk(Viimp)flkvimp(θjvimp) dVimp dθvimp. Secondly, we employed the model of Zheng et al (2005) to settle the collision process. Hence, we found the lift-off probability pij of sand after collision corresponding to incident speed Viimp and incident angle θjvimp. Meanwhile, by conducting statistics, we also found the probability density distributions (gij(Vlif) and gij(θlif)) of lift-off speed and lift-off angle as well as the conditional probability density distribution gij,vlif(θvlif) of angles for each lift-off speed.

- Statistics for lift-off sand. Since the probability of one incident event (Viimp, θjvimp) is Si and the probability of lift-off particles referring to the incident condition is pij, we first determined the probability of each lift-off speed and angle. In detail, the probability of each speed (Vlif) is represented as qij(Vlif) = Sijpijgij(Vlif) dVlif; the probability of each angle (θlif) is described as qij(θlif) = Sijpijgij(θlif) dθlif; and the conditional probability of angle (θvlif) corresponding to speed Vlif is expressed as qij,vlif(θvlif) = qij(Vlif)gij,vlif(θvlif). Then, we performed statistics for all possible incident conditions (namely traversal of both i and j). Therefore, we found the probability density distributions of lift-off parameters corresponding to incident distributions (flk(Vimp) and flkvimp(θvimp)). Detailed expressions can be found in section A.2 of the appendix.

- Hopping of lift-off sand. Firstly, we discretized the distribution ranges of lift-off speed and the corresponding lift-off angle determined in step 3 as we did in step 2. Secondly, based on the friction speed u* given in step 1, we determined the wind speed at the height that sand can reach with the help of formula (2). Thirdly, we used formula (1) for solving the saltation of sand with the lift-off condition (Vilif, θjvlif).

- Statistics for incident sand. After saltation of particles, new incident speed Viiimp and incident angle θ jjimp of saltating sand as well as their probability p'ij = flk (Vlifi ) .flkvlif(θjvlif) dVlif dθvlif were obtained. Then, we conducted statistics for all possible lift-off conditions as we did in step 3. We thus found probability density distributions (flk+1(Vimp) and flk+1(θimp)) of the incident velocity and incident angle as well as the conditional probability density distribution flk+1vimp(θvimp) of angles that have the same incident speed Vimp, for the (lk + 1)th loop.

- Condition of convergence. Judge whether both (flk+1(Vimp) − flk(Vimp))/flk(Vimp) <5% and (flk+1(θimp) − flk(θimp))/flk(θimp) < 5% reach or not. If yes, the calculation converges, or lk = lk + 1 and a new loop starts again. Probability density distributions of the incident sand (flk+1(Vimp) and flk+1vimp(θvimp)) are brought back into step 1, treated as the new incident condition. The iteration will not stop until the condition of convergence is reached. Once the calculation converges, the stable results including probability distributions of velocity and angle are output.

Figure 2. Flowchart of our model.

Download figure:

Standard image2.5. Parameters used during calculations

The sand diameters used to verify our model are 0.287, 0.36, 0.4 and 0.44 mm. The diameter D = 0.25 mm was chosen as the reference for studying the influence of various physical and atmospheric environments on the features of sand saltation on both Mars and Earth. This is because the typical diameters of sand particles on Mars range from 0.1 to 0.6 mm (Kok et al 2012), while those on Earth range from 0.15 to 0.25 mm (Shao 2008). To investigate the influence of particle diameter on the saltation of Martian grains, another two diameters, 0.35 and 0.5 mm, were employed.

Just as Zheng et al (2005) did, we chose k = k1 = k2 = 0.35 in the model, where k1 and k2 are normal and tangential restitution coefficients, respectively. An experimental study (Wang et al 2009) revealed that the speed of creep sand particles ranges from 0 to 0.27 m s−1 when the particle diameter is less than 0.5 mm. But the study of Xie and Zheng (2007) suggested that the influence of creep particles on the lift-off information is small within such a narrow range of creeping speed. Therefore, in our model here, the speed of sand on the bed Vsur was assumed to be 0 m s−1 for convenience. The choice of other random variables follows the work of Zheng et al (2005). For the impact angle, −π/2 < β <π/2. The contact angle is located within [θ0, θ0 + π/2] when 0 ⩽ θ0 ⩽ π /2 , while it is located within [θ0 − π/2, θ0) when π /2 < θ0 ⩽ π . In the following, subscripts x and y represent the horizontal and vertical components of the sand speed, respectively; subscripts e and m represent the results on Earth and Mars, respectively. Other parameters used during calculations are shown as follows. On Earth, gravity ge = 9.81 m s−2, the dynamic viscosity of air ηe = 1.78 × 10−5 kg m−1 s−1, the density of air ρa,e = 1.225 kg m−3 and the density of sand ρs,e = 2650 kg m−3. On Mars, the gravity gm = 3.71 −m s−2, the dynamic viscosity of air ηm = 1.3 × 10−5 kg m−1 s−1, the density of air ρa,m = 0.02 kg m−3 and the density of sand ρs,m = 3000 kg m−3 (Pähtz et al 2012).

For a better comparison between the results on Mars and those on Earth, the dimensionless friction speed (u*/u*ft) was employed to describe the wind strength. The u*ft represents the fluid threshold for aerodynamic entrainment and is expressed as u*ft = AN((ρs − ρa)gD/ρa + γ /(ρaD))0.5, AN = 0.111, γ = 2.9 × 10−4 N m−1 (Shao and Lu 2000). Based on some experimental studies (Rasmussen et al 2009, Ho et al 2011), the impact threshold of particles with D = 0.25 mm on Earth was determined to be 0.2 m s−1. For the Martian particles with D = 0.25, 0.35 and 0.50 mm, the impact thresholds were determined to be 0.2, 0.3 and 0.6 m s−1, respectively, according to some investigations (Almeida et al 2008, Kok 2010b, Pähtz et al 2012). In the following, we first calculated saltations on both Earth and Mars in the cases of u* = 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7 m s−1, respectively, and then calculated saltations in the cases of u*/u*ft = 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75 and 2.0, respectively. It should be noted that it is assumed that the saltation process has been initiated for all cases of wind strengths and therefore will continue as long as u*/u*ft > 1.0.

3. Model validation

3.1. Insensitivity to initial velocity distribution

Here, we tested the model with different initial distributions (see figure A.1 in the appendix). The diameter used here is D = 0.25 mm. The modeling was conducted under terrestrial conditions. The wind strength was set as u*/u*ft = 2.0. Three kinds of initial distributions (uniform, linear and exponential) were employed.

From figure A.1 in the appendix, it can be seen that different distributions of initial incident speeds converge to the same stable distribution of incident speed after iterations in the model. In fact, model tests suggest that the initial distribution of incident speed does not influence the final converged result but influences the time of convergence (figure 3). This reveals that a small difference between initial distribution and converged distribution means a short time to reach convergence. Generally, the established model is not sensitive to the initial distribution of incident speed and therefore the results obtained by our model are slightly affected by the initial distribution of incident speed.

Figure 3. The change in probability density distribution of resultant incident speed with iteration step (lk) during calculation. Panels (a), (b) and (c) represent the change of the resultant incident speed followed by the uniform, linear and exponential distributions of the initial incident speed, respectively.

Download figure:

Standard image3.2. Verification of the distribution of particle velocity

Because the sand particles used in the wind tunnel experiment (Kang et al 2008) are mixed (D = 0.36–0.44 mm), simulated results of D = 0.36, 0.4 and 0.44 mm were selected, respectively, to compare with wind tunnel experimental data (figure 4). The environment of the simulation is the same as experimental design and the friction speed of wind is u* = 0.65 m s−1. Figure 4 indicates that the distribution of horizontal lift-off speed is approximately symmetrical with a little left-skew, while that of vertical lift-off velocity satisfies the exponential law. It can be seen in the figure that the simulated distributions of lift-off velocities, both in the horizontal and vertical directions, agree well with experimental data. That is, the established model in this paper can predict the velocity distribution of saltating sand particles quantitatively.

Figure 4. Comparisons between experimental data and simulated results of our model. The dashed lines represent our simulated results and the circles represent experimental data from Kang et al (2008). Panels (a) and (b) show the distributions of lift-off velocities in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.

Download figure:

Standard image3.3. Verification of lift-off angles

The simulated distributions of lift-off angles are shown in figure A.2 in the appendix. It could be found that the obtained distributions are consistent with previous studies (Rice et al 1996, Dong et al 2002, Kang et al 2008). That is, the distribution of lift-off angle ranges widely from 0 to 180° and the angles are mainly distributed within 0–90°. Furthermore, we calculated the average lift-off angle of simulated results, as shown in figure 5. It can be seen that the simulated average angle is located within 40–50°. Since previous studies (Rice et al 1996, Dong et al 2002, Kang et al 2008) revealed that the average lift-off angle mainly ranges from 30° to 60°, the simulated average angles of our model are therefore consistent with previous studies. Hence, our model could predict the angle of particles in wind-blown sand.

Figure 5. The change in average lift-off angle with wind strength. The square symbols represent the simulated results. The dot lines show the main range of average lift-off angles in previous studies.

Download figure:

Standard image3.4. Verification of average coefficient of restitution

In figure 6, we compared the experimental average of the restitution coefficient (Gordon and McKenna Neuman 2009), defined as the ratio of average resultant lift-off speed to average resultant incident speed, with the simulated average of restitution coefficient. In the following, U represents the average value of incident speed. Both experimental data and simulated results suggest that the average of restitution coefficient decreases with the average incident speed. But it can also be seen that there is a small deviation from the experimental data for small incident speed of particles. In our opinion, this difference may come from the sample amounts for statistics between our simulated results and their measured results. However, comparison of the average restitution coefficient between simulation and experiment shows that the physical basis of our model for momentum transfer in sand–bed collision is acceptable.

Figure 6. The average of the restitution coefficient (average resultant lift-off speed/average resultant incident speed) versus the average resultant incident speed. The squares with error bars represent the experimental results and the stars represent the simulated results.

Download figure:

Standard image3.5. Section conclusion

The model established in the paper mainly includes hopping of sand in the air and sand–bed collision process. Model tests suggest that our model is not sensitive to the initial distribution of incident speed, and different initial distributions of incident speed will lead to the same converged distribution. The model proves to be able to predict the speed and angle of saltating particles and to show momentum transfer in sand–bed collision correctly. Therefore, our model can show us the motion of sand in real wind-blown sand in a terrestrial environment. Because of its physical basis, our model can be applied to study the aeolian process on other planets such as on Mars and give reliable information on saltating particles in extraterrestrial wind-blown sand.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The distributions of incident velocity and incident angle on both Mars and Earth

4.1.1. The distributions of incident velocity and incident angle under the same u*

Due to the unique physical and atmospheric environment, saltation can be sustained under a wind strength that is far below the aerodynamic threshold friction speed on Mars (Claudin and Andreotti 2006, Almeida et al 2008, Kok 2010a, 2010b). Here, we simulated the saltations of particles with diameter D = 0.25 mm under three different u* (0.3, 0.5 and 0.7 m s−1) on both Mars and Earth. The obtained distributions of incident speed and incident angle of saltating particles are shown in figure 7. They reveal that the distribution law of incident speed on Mars is almost the same as that on Earth as is the distribution law of incident angle. In detail, the distributions of vertical incident speed and resultant incident speed follow negative exponent law. The distribution of the horizontal incident speed satisfies the extreme value distribution. The distribution of incident angle is approximately Gaussian. The overall shapes of the distributions may be quite alike, but they scale differently. The proportion of low horizontal incident speeds on Mars, for instance, is systematically higher than on Earth and vice versa for high incident speeds. The large proportion of low speeds, which is consistent with the results of Kok (2010b), suggests that the average incident speed of saltating particles on Mars is lower than that on Earth in the case of the same wind strength. The simulated incident angle on Earth ranges from 0 to 180°, which is in agreement with the experimental studies (Dong et al 2002, Kang et al 2008, Rasmussen and Sorensen 2008). The obtained incident angle on Mars has the same range as on Earth.

Figure 7. The probability density distributions of horizontal incident speed Vimp,x (a), vertical incident speed Vimp,y (b), resultant incident speed Vimp (c) and incident angle θimp (d) on both Mars and Earth. The solid lines and the dashed lines represent the results on Earth and Mars, respectively. The black lines, red lines and blue lines represent the results for u* = 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7 m s−1 respectively.

Download figure:

Standard image4.1.2. The distributions of incident velocity and incident angle under the same u*/u*ft

To get a better understanding of the saltation of Martian particles and find the difference of saltations between Martian particles and terrestrial particles, we show here the change in dimensionless particle speeds with various dimensionless wind strengths because of the diversity of physical and atmospheric conditions. The dimensionless particle speed is defined as particle speed/friction speed (V/u*). The dimensionless wind strength is defined as friction speed/aerodynamic threshold friction speed (u*/u*ft).

All the results are shown in figure 8. It can be seen that the distribution law of dimensionless incident speed on Mars as well as incident angle is the same as that on Earth. The range of dimensionless incident speed on Mars is narrower than that on Earth. But the proportion that a small dimensionless speed occupies is larger than the proportion on Earth. The range of dimensionless resultant incident speed is much wider than that of dimensionless vertical incident speed but the same as that of dimensionless horizontal incident speed. This suggests the important role of horizontal incident speed during the sand–bed collision process (Kok 2010b).

Figure 8. The probability density distribution of dimensionless horizontal incident speed Vimp,x/u* (a), dimensionless vertical incident speed Vimp,y/u* (b), dimensionless resultant incident speed Vimp/u* (c) and incident angle (d) under different dimensionless wind strengths. Panels (a), (b) and (c) include the results of all five wind strengths (u*/u*ft = 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75 and 2.0) and panel (d) shows only the results of three wind strengths (u*/u*ft = 1.0, 1.25 and 1.5). The solid and open symbols represent the results of speeds on Earth and Mars, respectively. The solid and dashed lines are fitting curves for the results on Earth and Mars, respectively.

Download figure:

Standard imageInterestingly, we found that the distributions of dimensionless incident speeds hardly change with dimensionless wind strengths on both Mars and Earth. Hence, the results of all five wind strengths are fitted by one curve through employing the least-square method. As shown in figure 8(a), the distributions of dimensionless horizontal incident speeds on both Mars and Earth are well described by the extreme value distribution function. Figures 8(b) and (c) suggest a negative exponent law for both dimensionless vertical incident speeds and dimensionless resultant incident speeds. The fitting curves are shown in section A.3 of the appendix. These curves show us the difference of distribution laws of incident speeds between Martian particles and terrestrial particles quantitatively. They may also help in modeling wind-blown sand in the future.

Figure 8(d) reveals that the incident angles on both Mars and Earth range from 0 to 180° under different dimensionless wind strengths. The main domain of angle distribution is about 0–40°. With the change in dimensionless wind strength, on both Mars and Earth, the whole range remains almost unchanged but the main domain of incident angle becomes narrower. Under the same dimensionless wind strength, the incident angle on Mars has a narrower main domain than that on Earth. The distributions of incident angle on both Mars and Earth can be approximately described by a Gaussian function.

4.2. Average incident velocities on both Mars and Earth

Based on the distributions of particle speeds, we determined the average incident speeds on both Mars and Earth. Table 1 shows the scaling law of average incident speed with wind strength and the relationship between Martian particles' speed and terrestrial particles' speed.

Table 1. Average incident speeds on both Mars and Earth.

| Incident speed | Mars | Earth | Speed on Mars versus that on Earth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal speed | Uimp,x,m=1.55u*,m | Uimp,x,e=1.90u*,e | Uimp,x,m=0.81(u*,m/u*,e) Uimp,x,e |

| Vertical speed | Uimp,y,m=0.5u*,m | Uimp,y,e=0.65u*,e | Uimp,y,m=0.77(u*,m/u*,e) Uimp,y,e |

| Resultant speed | Uimp,m=2.2u*,m | Uimp,e=2.85u*,e | Uimp,m=0.77(u*,m/u*,e) Uimp,e |

From table 1 we can see that average incident speeds are roughly described by the formula U = Cu*(r2 > 0.85), where C is the coefficient. Here, u* is a measure of wind strength, C is thought to be the efficiency of a fluid medium in accelerating the speed of sand particles. Results of table 1 reveal that the obtained coefficient C of the velocity in the Martian environment is smaller than that of the velocity in the terrestrial environment, which can be explained by the unique property of CO2 on Mars.

Regarding the linear relationship between particle velocity and wind strength, we found the relationship between the incident velocity of saltating particles on Mars and that on Earth. Our finding suggests that the average incident speed on Mars can be related to that on Earth in the manner of Um∝Ueu*,m/u*,e. However, we cannot determine the relationship quantitatively until wind strengths are declared. Typically, for sand that has a diameter of D = 0.25 mm, wind strengths above which saltation occurs range from 0.2 to 1.0 m s−1 on Earth (Shao 2008), while wind strengths supporting saltation of the same size sand possibly range from 0.2 to 3.0 m s−1 on Mars (Almeida et al 2008, Kok 2010a, 2010b, Pähtz et al 2012). Thus, we find the ratios of the incident speed of saltating sand on Mars to that on Earth range from 10−1 to 101, which covers all the reported ratios (White et al 1979, Almeida et al 2008, Kok 2010a, Pähtz et al 2012). Nevertheless, as pointed out above, a definitive ratio depends on the real wind strengths on both Mars and Earth. For example, in the case of u* = 0.5 m s−1, which is a common wind strength both on Mars (Holstein-Rathlou et al 2010) and on Earth (Shao 2008), our result suggests that the average incident speed of Martian sand with D = 0.25 mm has the same order of magnitude as but a little lower than that of terrestrial sand.

Furthermore, we compared average incident speeds on Mars by our model with previous studies (Almeida et al 2008, Kok 2010b), as shown in figure 9. It can be seen that the average incident speeds obtained by our model increase with wind strength, which is in agreement with the results of Almeida et al (2008) qualitatively. But our results on the average incident speeds as well as the results of Kok (2010b) are far lower than theirs, because they ignored the splash process during their simulations (Kok 2010a). From the work of Almeida et al (2008), it can be found that the particle was assumed to lift off with an angle of 36° and a constant restitution coefficient 0.6, instead of a splash function. This treatment is an over-simplification and results in a very large particle speed. Since the effect of the splash process is included in our model, our results are relatively close to the results of Kok (2010b). However, we also can see that, indeed, our results are different from the results of Kok (2010b) both quantitatively and qualitatively. It can be found that when u*/u*ft < 0.5, our simulated speeds are very close to Kok's analytical results. Once u*/u*ft > 0.5, the difference between our results and Kok' results becomes evident and rises with an increase of u*/u*ft. These discrepancies come from the hypothesis that the particle speed has a weak dependence on wind strength. Therefore, the derived results can never change with wind strength. However, this may not be true.

Figure 9. Comparisons of the average incident speeds from simulated results and those from previous studies. Symbols are the simulated results of our model and dashed lines represent the results of previous studies. The violet line shows the results of Almeida et al (2008) and the red lines the results of Kok (2010b).

Download figure:

Standard imageAlthough Kok (2010b) cited some experimental studies (Namikas 2003, Rasmussen and Sorensen 2008, Creysells et al 2009, Ho et al 2011) to support the hypothesis, there are some doubtful points. Namikas (2003) did not measure the particle speed directly. He used various distributions of lift-off velocities to model the distributions of sand transport rate and then compared the modeling results with experimental data. He found that better agreement is reached if the average lift-off speed did not change with wind strength. Thus, Kok used this finding to support his idea. Here Q is defined as the sand transport rate. We studied the ratios Q/(u2* − u2*it) with various wind strengths quantitatively (for details see supplementary figure S1, available from stacks.iop.org/NJP/15/043014/mmedia). The results reveal that the ratios increase with wind strengths significantly. This suggests that the average speed of saltating particles near the sand bed changes with wind strength, according to the study of Ho et al (2011). Also, the ratios Q/(u2* − u2*it) in the study of Creysells et al (2009) show a significant change with wind strength (for details see supplementary figure S2) and therefore indicate the variation of average particle speed near the sand bed.

Because of the difficulty in the measuring technique, it is hard to get information on particles very close to the bed. The published speeds of particles (Rasmussen and Sorensen 2008, Creysells et al 2009, Ho et al 2011) were measured at the height 2–3 mm above the bed or higher. These measured results are not incident or lift-off velocities of particles really close to the bed. Rasmussen and Sorensen (2008) employed a laser-Doppler anemometer (LDA) to measure particle speeds with height in the cases of various wind strengths to study the change of average particle speed with height. Regarding these measured speeds, they inferred that the average particle speed with height at different wind strengths would intersect at the height of 2–3 mm. The average particle speed at the focus point is about 1.3 m s−1 and it did not vary with wind strength. However, it should be noted that when measuring the grain speeds close to the bed using LDA sensors, the validation ratio may be fairly poor (Li and McKenna Neuman 2012). Thus, for instance, many low-speed grains are discarded due to instrument settings; this may influence the calculated average speed. Besides, Yang et al (2011) measured the particle speed and the local wind field above the height of 0.5 mm simultaneously, with the help of particle imaging velocimetry (PIV) and fluorescent tracer particles. Their results showed that the average particle speed decreases with a decrease of height at first but tends to a stable value near the bed. Thus, the inferred focus may be avoided. Therefore, the relationship between the average particle speed and height as well as the focus point needs further experimental evidence. Besides, the experimental design and material used by Creysells et al (2009) and Ho et al (2011) are the same. Nevertheless, the measured sand transport rate of Creysells et al (2009) at the same wind strength is an order of magnitude larger than that of Ho et al (2011) (for details see supplementary figure S3). Pähtz et al (2012) explained that such a big difference may come from the effect of wind tunnel size. Thus, we believe that this big difference results in unreliability in supporting the weak dependence of particle speed near the bed on wind strength.

Some new models were established to study the development and stability of wind-blown sand (Andreotti 2004, Lämmel et al 2012), but their results suggest that the dominant role of saltation is never replaced. That is, the incident and the lift-off velocities of particles will change with wind strength. In fact, the wind speed above the 'Bagnold focus' in steady-state saltation will increase with wind strength (Kok et al 2012); therefore, the saltating particles can obtain more momentum transferred from the air and get a larger speed. Kok et al (2012) also stated that 'although the mean speed of particles at the surface thus remains approximately constant with u*, the probability distribution of particles' speed at the surface does not'. Indeed, the probability distribution of particle speed near the sand bed will broaden. The probability of high speed increases with u* and that of low speed therefore decreases. So, it is reasonable that our simulated average incident speeds change with wind strength. However, in comparison with Kok et al (2012), our results reveal that the average incident speed increases with wind strength evidently. This difference may come from the consideration of incident angle in our model but neglect of incident angle in Kok's numerical model. Therefore, the influence of incident angle on the movements of wind-blown sand should be addressed in a future study. Besides, the response of particle velocity near the bed to wind strength needs experimental verification.

Moreover, we studied the influence of particle diameters on the average incident speed on Mars. Our simulated results are compared with the theoretical results of Kok (2010b). From figure 9, it can be seen that the theoretical results of Kok (2010b) are slightly affected by particle diameter, whereas our simulated results are significantly influenced by particle diameter. The average incident speeds of particles with different diameters increase with wind strength and focus at the ratio u*/u*ft of about 1.5. When u*/u*ft < 1.5, large particles have a smaller average incident speed than small particles. Once u*/u*ft > 1.5, large particles have a bigger average incident speed than small particles. These phenomena could be physically understood on the basis of the influence of particle diameter on the drag force and aerodynamic entrainment threshold.

4.3. Average incident angles on both Mars and Earth

Figure 10 shows the variation of average incident angles with both wind strength u* and dimensionless wind strength u*/u*ft. The simulated average incident angles on Mars, as well as on Earth, decrease with both wind strength and dimensionless wind strength at first, which is consistent with the results of a wind tunnel experiment (Cheng et al 2009). Further, the average incident angles tend to a stable value with an increase in both wind strength and dimensionless wind strength. The simulated incident angles on Mars as well as Earth follow a negative exponent law with both wind strength and dimensionless wind strength (see section A.4 of the appendix). At the same wind strength, the average incident angle on Mars is larger than that on Earth. At the same dimensionless wind strength, the average incident angle on Mars turns out to be smaller than that on Earth. This can be explained by the very low density of CO2 and low gravity on Mars.

Figure 10. The variation of average incident angles with wind strengths (a) and dimensionless wind strengths (b).

Download figure:

Standard imageFurthermore, we compared the average incident angles on Mars obtained by our model with the results of previous studies (White et al 1976, Almeida et al 2008), as shown in figure 11. It reveals that the average incident angles of White et al (1976) are about 3° and are much less than both our results and the results of Almeida et al (2008). This big difference lies in the way the trajectory is calculated. In the work of White et al (1976), the particle was released vertically from the bed into the air with a large initial speed. Thus, the particle could fly in the air for a very long time and get more energy from the wind as well as a very large horizontal speed compared to vertical speed. Since the incident angle is defined as the angle between the resultant speed and its horizontal component, the very large horizontal speed results in a very small incident angle. Also, they ignored the interaction between the particle and the sand bed during saltation. The results of Almeida et al (2008) indicate that the average incident angles on Mars decrease with wind strength but the change is slight. Our results show that the average incident angles on Mars decrease with wind strength significantly at first and then tend to a stable value. Also, the average incident angles on Mars increase with particle diameter. This could be explained as follows. Usually, a large particle is hard to drive by air. At the same wind strength, a small particle gets a larger acceleration than a large particle. Thus, the small particle will get a larger horizontal speed than the large particle. According to the definition of incident angle, the incident angle of a small particle is therefore smaller than that of a large particle. From figure 11 we can see that the average incident angles of Martian particles with D = 0.6 mm are about 10°. At the same dimensionless wind strength, our results are 2–3 times larger than theirs. A possible reason is that they ignored the splash process (Kok 2010a) and the randomness of sand–bed collision (Zheng et al 2005), which are key for determining the speeds of particles.

Figure 11. Comparisons of the average incident angles on Mars from simulated results and those from previous studies. Symbols are simulated results of our model and dashed lines represent the results of previous studies. The dashed line shows the results of White et al (1976) and the dotted line shows the results of Almeida et al (2008).

Download figure:

Standard image5. Conclusions

In this paper we have established a model to investigate the saltation of sand in the steady state, mainly considering the hopping of sand in the air and sand–bed collision process. The model is not sensitive to the initial distribution of incident speed. Different initial distributions of incident speed affect the time of convergence but not the final converged distribution. The model proves able to predict the speed and angle of saltating particles and show momentum transfer in sand–bed collision correctly. Therefore, our model can show us the motion of sand in a terrestrial environment. Because of its physical basis, our model can be applied to study the aeolian process on other planets such as Mars and give reliable information on particles in extraterrestrial saltation of wind-blown sand.

Depending on this model, we studied the incident velocity and incident angle of saltating particles on Mars. The probability density distributions of both the dimensionless vertical incident speed and the dimensionless resultant incident speed follow a negative exponent law. The probability density distribution of the dimensionless horizontal incident speed satisfies the extreme value function. The probability density distribution of incident angle can be described by a Gaussian function. The average incident speeds on both Mars and Earth, including the horizontal, the vertical and the resultant incident speeds, slightly increase with wind strength. The ratios of the average incident speed of saltating sand on Mars to that on Earth range from 10−1 to 101, but a definitive ratio depends on the real wind strengths on both Mars and Earth. At the same wind strength, the average incident angle on Mars is larger than that on Earth. But at the same dimensionless wind strength, the average incident angle on Mars is smaller than that on Earth. This is possibly due to the unique property of CO2 and low gravity on Mars.

Also, the lift-off velocity and lift-off angle of Martian saltating particles can be obtained by our model. Therefore, it is possible for us to study other features of the saltation of wind-blown sand, such as the mean saltation length and the sand transport rate. Besides, the simulated results of our model, including the average incident speed and incident angle, were compared with previous studies. The comparisons suggest that: (i) the stochastic particle–bed collision is very important for the saltation of wind-blown sand; and (ii) the influence of incident angle on the development and stability of the saltation should be addressed in a future study.

Figure A.1. The probability density distributions of initial resultant incident speeds (a) and converged resultant incident speeds (b). The solid line (black), dashed line (red) and dotted line (blue) represent the uniform, linear and exponential distributions of initial incident velocities, respectively, in (a) and the corresponding converged results, respectively, in (b).

Download figure:

Standard imageFigure A.2. The probability density distributions of simulated lift-off angles.

Download figure:

Standard imageAcknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (numbers 11072097, 11232006, 11202088, 10972164, 11121202), National Key Technology R&D Program (2013BAC07B01), the Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (number 308022) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (numbers lzujbky-2009-k01, lzujbky-2012-203) and a project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (number 2009CB421304). The authors express their sincere appreciation for the support.

Appendix

A.1. The analytic solutions of speeds of lift-off particles

The following formulae show the derived velocity expressions of the rebounded and ejected sand in a collision event by the model (Zheng et al 2005)

Here, Vreb x (Veje x) and Vreb y (Veje y) are the velocities of rebounded (ejected) sand in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. Vimp is the velocity of incident sand and Vsur is the speed of sand on the bed. α, β and θ0 are the contact angle, impact angle and incident angle, respectively. k is the restitution coefficient.

A.2. The probability density distributions of lift-off parameters

where flk (Vlif ) and flk (θlif ) are population distributions of lift-off speed and lift-off angle, respectively. fvliflk (θvlif ) is the conditional distribution of lift-off angle for each speed.

A.3. The fitting curves for lift-off speeds

The fitting curves (A.9), (A.11) and (A.13) are for Martian particles, and the other three (A.8), (A.10) and (A.12) are for terrestrial particles.