About

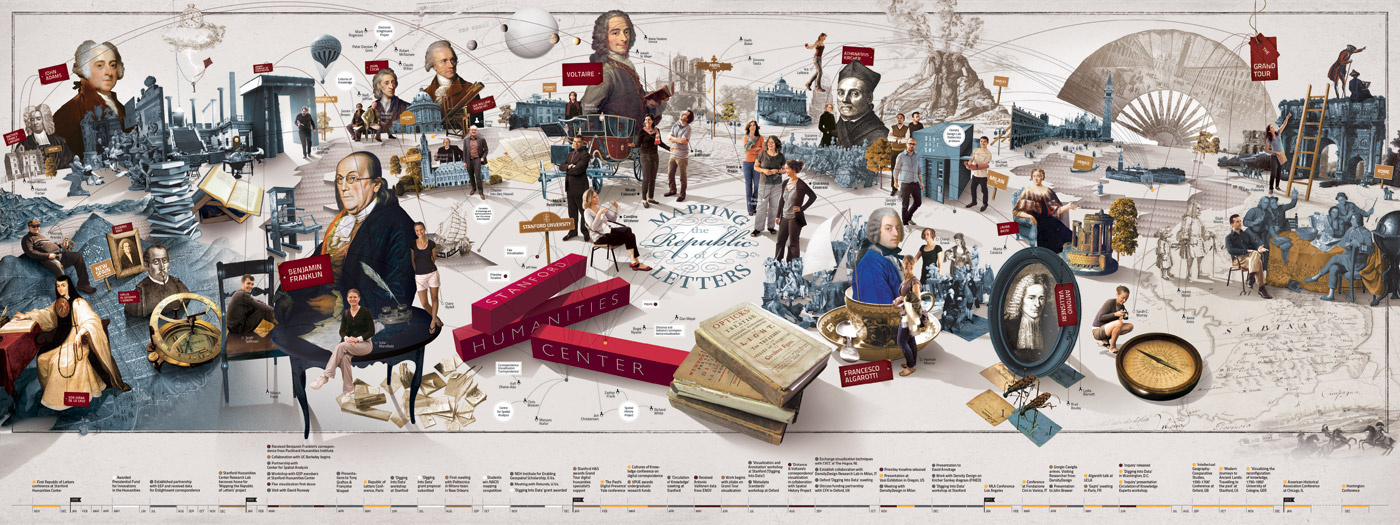

Palladio is a product of the NEH Implementation grant (July 2013-June 2016), Networks in History: Data-driven tools for analyzing relationships across time. Our goal was to understand how to design graphical interfaces based on humanistic inquiry. We oriented the project around the development of a general-purpose suite of visualization and analytical tools based on the prototypes created for the Mapping the Republic of Letters project, which examines the scholarly communities and networks of knowledge during the period 1500-1800.

Modeling Historical Data to Understand the Past

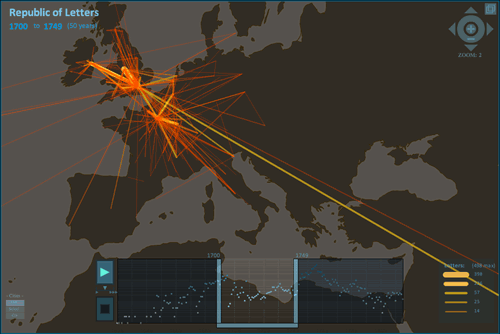

In 2009, students in Jeff Heer’s CS448b Data Visualization class at Stanford produced an award-winning interactive visualization tool for the “Mapping the Republic of Letters” project that let historians explore 17th and 18th century correspondence in a novel way. Early modern communication networks previously only imagined in the minds of historians could now be seen graphically as pulsing arteries connecting the centers of Enlightenment thought. For the Stanford team of four core humanities faculty, tens of graduate students, and numerous international partners, the tool offered exciting new possibilities for producing knowledge. Many cited it as an example of data visualization transforming historical research. But it is the way the visualization failed to help us answer actual research questions that made us realize that we needed become actively engaged in the design of tools.

Later that year we were awarded a Digging Into Data grant in collaboration with Robert McNamee’s Electronic Enlightenment Project and Chris Weaver, developer of Improvise. Since ours was an early modern project, we looked immediately to Athanasius Kircher (the subject of one of our case studies), Joseph Priestley, and William Playfair for inspiration, but also to concurrent projects like Moritz Stefaner’s Well-Formed Eigenfactor. At the Stanford lab, we worked closely with a number of information and visual designers including Scott Murray, Jesse Kriss, and Elijah Meeks. Developments out of the Stanford Vis Group, specifically Protovis (and, later, D3.js), allowed us to think very freely about how to give graphical form to our heterogenous, idiosyncratic, and multi-dimensional data rather than trying to squeeze meaning out of tools built around statistical analysis. With the award of an NEH grant, we began a partnership with DensityDesign research lab where we were fortunate to find a kindred spirit, Giorgio Caviglia, whose own research interest in uncertainty and complexity complemented our own. For the next four years of the seven-year project, Giorgio worked almost continuously in our lab at Stanford, first while a PhD candidate and later as a Postdoctoral researcher. This sustained interdisciplinary engagement was essential to our success in building a graphical interface for data-driven historical research.

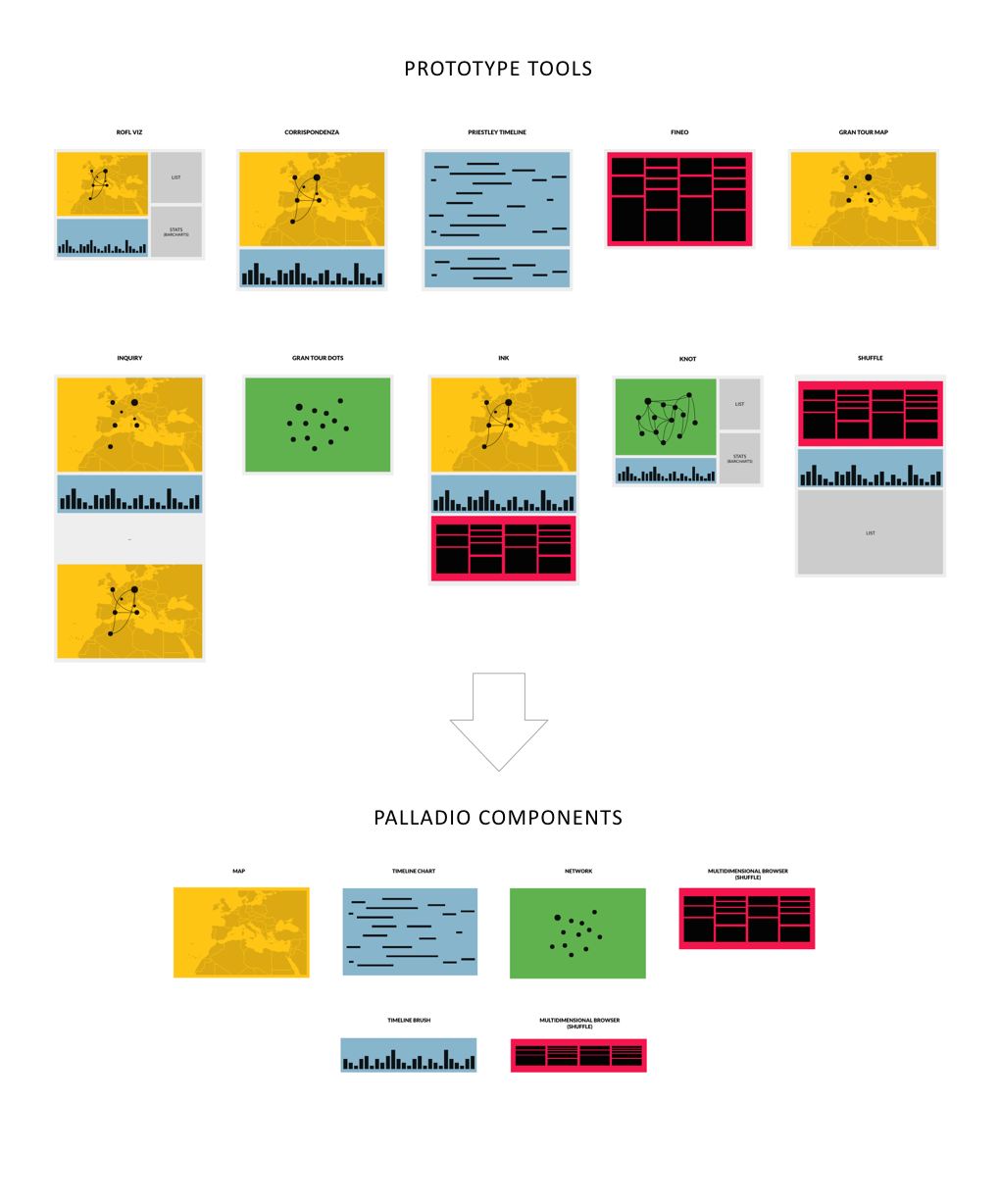

We developed several prototype visualizations in an attempt to match graphical interfaces to humanistic methods, with the NEH Implementation grant, finally arriving at the integrated application Palladio. One of those prototype tools, Shuffle, was developed by Ethan Jewett, who became the lead developer of Palladio. The figure below shows how we extracted from our prototype tools the graphic views of data that were the most effective and brought those elements together in one multi-faceted tool. What is missing from the diagram is the experience of using the tool. Palladio is tool for reflective practice. It is an environment that supports thinking through data. Like so many historical sources, the correspondence metadata at the heart of “Mapping the Republic of Letters” is incomplete in unpredictable ways. Historians work with fragments of information from the past, not complete data sets. The discipline does not offer models against which to test hypotheses. Instead, tools need to support scholars in building an understanding of the historical material through working with it. To create Palladio, we had to externalize what is a very internal, individual, thought process.